Origins and Development Ofthe Field Ofprehistory in Burma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8D Myanmar Delights Yangon – Bagan – Mandalay – Heho – Isle Lake

8D MYANMAR DELIGHTS YANGON – BAGAN – MANDALAY – HEHO – ISLE LAKE The tour showcases the rich cultures and historical heritage of this Golden destination which boasts of an authentic traditional legacy. The tour is more focused on a spiritual aspect showcasing the rich Buddhist cultures and unmatched archeological attractions the destination offers. ITINERARY Day 1: Singapore - Yangon by morning flight – Full Day Yangon Sightseeing (L/D) Upon arrival, you will be welcomed by your guide to start your introductory tour through Yangon City. Start to visit around Yangon City Center surrounded by various colonial style buildings of World War II, City Hall & Independent Monument for photo shoots & witness the daily life of local people. Lunch at a local restaurant. After lunch, visit to Kandawgyi Nature Park - a scenic park with a lovely view of famous Kandaweyi Lake & Karaweik Royal Barge for photo opportunities. Early evening visit Shwedagon Pagoda - the most sacrosanct Buddhist pagoda in Myanmar. As per legend, it was developed over 2600 years back which make it the most established Buddhist Pagoda on the planet and revamped a few times before taking its present shape in the fifteenth century. The 8-sided focal stupa is 99 meters tall, plated with gold leaf and is encompassed by 64 little stupas. Pursue the guide's lead around this huge complex and realize why this sanctuary is so adored. Dinner at a local restaurant. Overnight at selected hotel in Yangon. Optional: buffet dinner with traditional cultural show at Karaweik Palace Royal Barge Floating Restaurant USD 15 per person. Distance and journey time: Yangon Airport to Yangon City Centre (20 km): 30 – 60 mins + Traffic. -

Village Tract of Mandalay Region !

!. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. !. Myanmar Information Management Unit !. !. !. Village Tract of Mandalay Region !. !. !. !. 95° E 96° E Tigyaing !. !. !. / !. !. Inn Net Maing Daing Ta Gaung Taung Takaung Reserved Forest !. Reserved Forest Kyauk Aing Mabein !. !. !. !. Ma Gyi Kone Reserved !. Forest Thabeikkyin !. !. Reserved Forest !. Let Pan Kyunhla Kone !. Se Zin Kone !. Kyar Hnyat !. !. Kanbalu War Yon Kone !. !. !. Pauk Ta Pin Twin Nge Mongmit Kyauk Hpyu !. !. !. Kyauk Hpyar Yae Nyar U !. Kyauk Gyi Kyet Na !. Reserved Hpa Sa Bai Na Go Forest Bar Nat Li Shaw Kyauk Pon 23° N 23° Kyauk War N 23° Kyauk Gyi Li Shaw Ohn Dan Lel U !. Chaung Gyi !. Pein Pyit !. Kin Tha Dut !. Gway Pin Hmaw Kyauk Sin Sho !. Taze !. !. Than Lwin Taung Dun Taung Ah Shey Bawt Lone Gyi Pyaung Pyin !. Mogoke Kyauk Ka Paing Ka Thea Urban !. Hle Bee Shwe Ho Weik Win Ka Bar Nyaung Mogoke Ba Mun !. Pin Thabeikkyin Kyat Pyin !. War Yae Aye !. Hpyu Taung Hpyu Yaung Nyaung Nyaung Urban Htauk Kyauk Pin Ta Lone Pin Thar Tha Ohn Zone Laung Zin Pyay Lwe Ngin Monglon !. Ye-U Khin-U !. !. !. !. !. Reserved Forest Shwe Kyin !. !. Tabayin !. !. !. !. Shauk !. Pin Yoe Reserved !. Kyauk Myaung Nga Forest SAGAING !. Pyin Inn War Nat Taung Shwebo Yon !. Khu Lel Kone Mar Le REGION Singu Let Pan Hla !. Urban !. Koke Ko Singu Shwe Hlay Min !. Kyaung !. Seik Khet Thin Ngwe Taung MANDALAY Se Gyi !. Se Thei Nyaung Wun Taung Let Pan Kyar U Yin REGION Yae Taw Inn Kani Kone Thar !. !. Yar Shwe Pyi Wa Di Shwe Done !. Mya Sein Sin Htone Thay Gyi Shwe SHAN Budalin Hin Gon Taing Kha Tet !. Thar Nyaung Pin Chin Hpo Zee Pin Lel Wetlet Kyun Inn !. -

46399E642.Pdf

PGDS in DOS Myanmar Atlas Map Population and Geographic Data Section As of January 2006 Division of Operational Support Email : [email protected] ((( Yüeh-hsi ((( ((( Zayü ((( ((( BANGLADESHBANGLADESH ((( Xichang ((( Zhongdian ((( Ho-pien-tsun Cox'sCox's BazarBazar ((( ((( ((( ((( Dibrugrh ((( ((( ((( (((Meiyu ((( Dechang THIMPHUTHIMPHU ((( ((( ((( Myanmar_Atlas_A3PC.WOR ((( Ningnan ((( ((( Qiaojia ((( Dayan ((( Yongsheng KutupalongKutupalong ((( Huili ((( ((( Golaghat ((( Jianchuan ((( Huize ((( ((( ((( Cooch Behar ((( North Gauhati Nowgong (((( ((( Goalpara (((( Gauhati MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( Dinhata ((( ((( Gauripur ((( Dongch ((( ((( ((( Dengchuan ((( Longjie ((( Lalmanir Hat ((( Yanfeng ((( Rangpur ((( ((( ((( ((( Yuanmou ((( Yangbi((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Shillong ((((( Xundia ((( ((( Hai-tzu-hsin ((( Yongping ((( Xiangyun ((( ((( ((( Myitkyina ((( ((( ((( Heijing ((( Gaibanda NayaparaNayapara ((((( ((( (Sha-chiao(( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yipinglang ((( Baoshan TeknafTeknaf ButhidaungButhidaung (((TeknafTeknaf ((( ((( Nanjian ((( !! ((( Tengchong KanyinKanyin((( ChaungChaung !! Kunming ((( ((( ((( Anning ((( ((( ((( Changning MaungdawMaungdaw ((( MaungdawMaungdaw ((( ((( Imphal Mymensingh ((( ((( ((( ((( Jiuyingjiang ((( ((( Longling 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yunxian ((( ((( ((( ((( -

TRENDS in MANDALAY Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY Photo credits Paul van Hoof Mithulina Chatterjee Myanmar Survey Research The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 11 2. Methodology 14 2.1 Objectives 15 2.2 Research tools 15 3. Introduction to Mandalay region and participating townships 18 3.1 Socio-economic context 20 3.2 Demographics 22 3.3 Historical context 23 3.4 Governance institutions 26 3.5 Introduction to the three townships participating in the mapping 33 4. Governance at the frontline: Participation in planning, responsiveness for local service provision and accountability 38 4.1 Recent developments in Mandalay region from a citizen’s perspective 39 4.1.1 Citizens views on improvements in their village tract or ward 39 4.1.2 Citizens views on challenges in their village tract or ward 40 4.1.3 Perceptions on safety and security in Mandalay Region 43 4.2 Development planning and citizen participation 46 4.2.1 Planning, implementation and monitoring of development fund projects 48 4.2.2 Participation of citizens in decision-making regarding the utilisation of the development funds 52 4.3 Access to services 58 4.3.1 Basic healthcare service 62 4.3.2 Primary education 74 4.3.3 Drinking water 83 4.4 Information, transparency and accountability 94 4.4.1 Aspects of institutional and social accountability 95 4.4.2 Transparency and access to information 102 4.4.3 Civil society’s role in enhancing transparency and accountability 106 5. -

AROUND MANDALAY You Cansnoopaboutpottery Factories

© Lonely Planet Publications 276 Around Mandalay What puts Mandalay on most travellers’ maps looms outside its doors – former capitals with battered stupas and palace walls lost in palm-rimmed rice fields where locals scoot by in slow-moving horse carts. Most of it is easy day-trip potential. In Amarapura, for-hire rowboats drift by a three-quarter-mile teak-pole bridge used by hundreds of monks and fishers carrying their day’s catch home. At the canal-made island capital of Inwa (Ava), a flatbed ferry then a horse cart leads visitors to a handful of ancient sites surrounded by village life. In Mingun – a boat ride up the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) from Mandalay – steps lead up a battered stupa more massive than any other…and yet only a AROUND MANDALAY third finished. At one of Myanmar’s most religious destinations, Sagaing’s temple-studded hills offer room to explore, space to meditate and views of the Ayeyarwady. Further out of town, northwest of Mandalay in Sagaing District, are a couple of towns – real ones, the kind where wide-eyed locals sometimes slip into approving laughter at your mere presence – that require overnight stays. Four hours west of Mandalay, Monywa is near a carnivalesque pagoda and hundreds of cave temples carved from a buddha-shaped moun- tain; further east, Shwebo is further off the travelways, a stupa-filled town where Myanmar’s last dynasty kicked off; nearby is Kyaukmyaung, a riverside town devoted to pottery, where you can snoop about pottery factories. HIGHLIGHTS Join the monk parade crossing the world’s longest -

Rakhine State

Myanmar Information Management Unit Township Map - Rakhine State 92° E 93° E 94° E Tilin 95° E Township Myaing Yesagyo Pauk Township Township Bhutan Bangladesh Kyaukhtu !( Matupi Mindat Mindat Township India China Township Pakokku Paletwa Bangladesh Pakokku Taungtha Samee Ü Township Township !( Pauk Township Vietnam Taungpyoletwea Kanpetlet Nyaung-U !( Paletwa Saw Township Saw Township Ngathayouk !( Bagan Laos Maungdaw !( Buthidaung Seikphyu Township CHIN Township Township Nyaung-U Township Kanpetlet 21° N 21° Township MANDALAYThailand N 21° Kyauktaw Seikphyu Chauk Township Buthidaung Kyauktaw KyaukpadaungCambodia Maungdaw Chauk Township Kyaukpadaung Salin Township Mrauk-U Township Township Mrauk-U Salin Rathedaung Ponnagyun Township Township Minbya Rathedaung Sidoktaya Township Township Yenangyaung Yenangyaung Sidoktaya Township Minbya Pwintbyu Pwintbyu Ponnagyun Township Pauktaw MAGWAY Township Saku Sittwe !( Pauktaw Township Minbu Sittwe Magway Magway .! .! Township Ngape Myebon Myebon Township Minbu Township 20° N 20° Minhla N 20° Ngape Township Ann Township Ann Minhla RAKHINE Township Sinbaungwe Township Kyaukpyu Mindon Township Thayet Township Kyaukpyu Ma-Ei Mindon Township !( Bay of Bengal Ramree Kamma Township Kamma Ramree Toungup Township Township 19° N 19° N 19° Munaung Toungup Munaung Township BAGO Padaung Township Thandwe Thandwe Township Kyangin Township Myanaung Township Kyeintali !( 18° N 18° N 18° Legend ^(!_ Capital Ingapu .! State Capital Township Main Town Map ID : MIMU1264v02 Gwa !( Other Town Completion Date : 2 November 2016.A1 Township Projection/Datum : Geographic/WGS84 Major Road Data Sources :MIMU Base Map : MIMU Lemyethna Secondary Road Gwa Township Boundaries : MIMU/WFP Railroad Place Name : Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) translated by MIMU AYEYARWADY Coast Map produced by the MIMU - [email protected] Township Boundary www.themimu.info Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit Yegyi Ngathaingchaung !( State/Region Boundary 2016. -

Environmental Assessment and Review Framework

Environmental Assessment and Review Framework Document Status: Final Projet Number: 47152 July 2016 Myanmar: Irrigated Agriculture Inclusive Development Project This environmental assessment and review framework is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments to the legal or other status of any territory or area. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 01September 2015) Currency unit – Myanmar Kyats Kyats 1.00 = US $0.0007855 US $1.00 = MMK 1,273 ABBREVIATIONS ACC – agricultural coordination center ADB – Asian Development Bank AP – affected people CDZ – Central Dry Zone CO2 – Carbon dioxide DOA – Department of Agriculture, MOALI EA – Executing Agency EARF – Environmental Assessment and Review Framework ECD – Environmental Conservation Department, MOECAF EHSO – Environment, Health and Safety Officer EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment EMP – Environmental Management Plan FESR – Framework for Economic and Social Reforms FGD – focus group discussion GEF – Global Environment Facility GHG – greenhouse gas GRM – Grievance Redress Mechanism ha – hectare IEE – Initial Environmental Examination IA – Implementing Agency IAIDP – Irrigated Agriculture Inclusive Development Project IWUMD – Irrigation -

QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT April to June 2017

NATIONAL COMMUNITY DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project No: H814-MM and IDA Credit no: 56870 QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT April to June 2017 Submitted in compliance with Section II A of the Financing Agreement between the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and the International Development Association Presented by: National Community Driven Development Secretariat Department of Rural Development 14 August 2017 NCDDP Quarterly Progress Report (April – June 2017) List of Abbreviations and Acronyms BER - Bid Evaluation Report BG - Block Grant BGA - Block Grant Agreement CFA - Community Force Account CDD - Community-driven Development DRD - Department of Rural Development DSW - Department of Social Welfare ECOPs - Environmental Codes of Practice EMP - Environmental Management Plan EOI - Expression of Interest (procurement document) ESMF - Environmental and Social Management Framework GESI - Gender Empowerment and Social Inclusion GWG - Gender Working Group MEB - Myanmar Economic Bank NOL - No-Objection Letter (WB document) OM - Operation Manual PSC - Performance Security Guarantee PMIS - Project Management Information System RFP - Request for Proposals RFQ - Request for Quotations TOF - Training of Facilitators TTF - Training of Technical Facilitators TOT - Training of Trainers TS - Township TTA - Township Technical Assistance UTA - Union Level Technical Assistance VL - Village Leader VTDSC - Village Tract Development Support Committee VPSC - Village Project Support Committee VTDP - Village Tract Development Plan VTPSC - Village Tract Project Support -

THAN TUN, M.A., B.L., Ph

THE ROYAL ORDERS OF BURMA, A.D. 1598-1885 PART FOUR, A.D. 1782-1787 Edited with Introduction, Notes and Summary in English of Each Order by THAN TUN, M.A., B.L., Ph. D. (London) Former Professor of History, Mandalay University KYOTO THE CENTRE FOR SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES, KYOTO UNIVERSITY 1986 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The editor owes much gratitude to THE CENTRE FOR SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES KYOTO UNIVERSITY for research fecilities given to him in editing these Royal Orders of Burma and to have them published under its auspices. He is also thankful to THE TOYOTA FOUNDATION financial aid to publish them. iv CONTENTS Acknowledgement iv List of colleagues who helped in collecting the Royal Orders vi Introduction vii Chronology 1782-1787 xxiv King's Own Calendar, 1806-1819 xxxiii Summary of Each Order in English 1 Royal Orders of Burma in Burmese 211 v List of colleagues who helped in collecting the Royal Orders Aung Kyaw (Chaung U) Aung Myin Chit So Myint Htun Yee Khin Htwe Yi Khin Khin Khin Khin Gyi Khin Khin Sein Khin Lay Khin Maung Htay sKhin Myo Aye Khin Nyun (Mrs Thein Than Tun) Khin Yi (Mrs Than Tun) Kyaw Kyaw Win Mya Mya Myine Myine Myint Myint Myint Htet Myint Myint Than Myo Myint Ni Ni Myint Ni Toot Nyunt Nyunt Way Ohn Kyi (Chaung U) Ohn Myint Oo Pannajota Sai Kham Mong San Myint (Candimala) San Nyein San San Aye Saw Lwin Sein Myint Than Than Thant Zin (Mawlike) Thaung Ko Thein Hlaing Thein Than Tun Thoung Thiung Tin Maung Yin Tin Tin Win Toe Hla Tun Nwe Tun Thein Win Maung Yi Yi Yi Yi Aung vi INTRODUCTION LIKEAniruddha (Anawyatha Min Saw), Hti Hlaing Shin (Kyanzittha), Hanthawady Sinbyu Shin (Bayin Naung), Alaungmintaya (U Aung Zayya) and Mindon after him, King Badon (Bodawpaya) was a usurper on the Burmese throne and like his every other counterpart, he tried to rule with benevolence. -

Laboratory Aspects in Vpds Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation

Laboratory Aspect of VPD Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation Dr Ommar Swe Tin Consultant Microbiologist In-charge National Measles & Rubella Lab, Arbovirus section, National Influenza Centre NHL Fever with Rash Surveillance Measles and Rubella Achieving elimination of measles and control of rubella/CRS by 2020 – Regional Strategic Plan Key Strategies: 1. Immunization 2. Surveillance 3. Laboratory network 4. Support & Linkages Network of Regional surveillance officers (RSO) and Laboratories NSC Office 16 RSOs Office Subnational Measles & Rubella Lab, Subnational JE lab National Measles/Rubella Lab (NHL, Yangon) • Surveillance began in 2003 • From 2005 onwards, case-based diagnosis was done • Measles virus isolation was done since 2006 • PCR since 2016 Sub-National Measles/Rubella Lab (PHL, Mandalay) • Training 29.8.16 to 2.9.16 • Testing since Nov 2016 • Accredited in Oct 2017 Measles Serology Data Measles Measles IgM Measles IgM Measles IgM Test Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 1766 1245 452 69 2012 1420 1182 193 45 2013 328 110 212 6 2014 282 24 254 4 2015 244 6 235 3 2016 531 181 334 16 2017 1589 1023 503 62 Rubella Serology Data Rubella Test Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 425 96 308 21 2012 195 20 166 9 2013 211 23 185 3 2014 257 29 224 4 2015 243 34 196 13 2016 535 12 511 12 2017 965 8 948 9 Measles Genotypes circulating in Myanmar 1. Isolation in VERO h SLAM cell line 2. Positive culture shows syncytia formation 3. Isolated MeV or sample by PCR 4. Positive PCR product is sent to RRL for sequencing 5. -

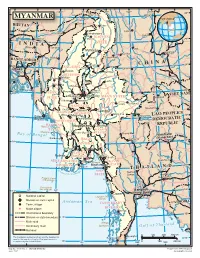

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

MYANMAR A? Flood Kachin, Shan (North) State and Sagaing, Mandalay, Magway Region Imagery Analysis: 25 July 2020 | Published 5 August 2020 | Version 1.0 FL20200730MMR

MYANMAR A? Flood Kachin, Shan (North) State and Sagaing, Mandalay, Magway Region Imagery analysis: 25 July 2020 | Published 5 August 2020 | Version 1.0 FL20200730MMR 94?40'0"E 95?20'0"E 96?0'0"E 96?40'0"E 97?20'0"E M O H N Y I N M Y I T K Y I N A H K A M T I Map location T A M U K A T H A K A C H I N B H A M O M Y A N M A R N " 0 ' 0 ? N 4 " 2 0 ' 0 ? 4 2 M AW L A I K K A W L I N M U S E M O N G M I T N " 0 ' 0 2 N ? " 3 0 ' 2 0 2 ? K A N B A L U Satellite detected water extent as 3 2 S A G A I N G of 25 July 2020 in central part of P A L A U N G S E L F - A D M I N I S T E R E D Z O N E Myanmar This map illustrates satellite-detected surface K A L E L A S H I O S H A N ( N O R T H ) waters over Kachin, Shan (North) State and MOGOK Sagaing, Mandalay, Magway Region of Myanmar as observed from a Terra(MODIS) L A S H I O N " 0 image acquired on 25 July 2020 due to the ' S H W E B O 0 4 N ? " 2 0 ' 2 current monsoon rains.