Listening and Learning About Israel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

מכון ירושלים לחקר ישראל Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies שנתון

מכון ירושלים לחקר ישראל Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies שנתון סטטיסטי לירושלים Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem 2016 2016 לוחות נוספים – אינטרנט Additional Tables - Internet לוח ג/19 - אוכלוסיית ירושלים לפי קבוצת אוכלוסייה, רמת הומוגניות חרדית1, רובע, תת-רובע ואזור סטטיסטי, 2014 Table III/19 - Population of Jerusalem by Population Group, Ultra-Orthodox Homogeneity Level1, Quarter, Sub-Quarter, and Statistical Area, 2014 % רמת הומוגניות חרדית )1-12( סך הכל יהודים ואחרים אזור סטטיסטי ערבים Statistical area Ultra-Orthodox Jews and Total homogeneity Arabs others level )1-12( ירושלים - סך הכל Jerusalem - Total 10 37 63 849,780 רובע Quarter 1 10 2 98 61,910 1 תת רובע 011 - נווה יעקב Sub-quarter 011 - 3 1 99 21,260 Neve Ya'akov א"ס .S.A 0111 נווה יעקב )מזרח( Neve Ya'akov (east) 1 0 100 2,940 0112 נווה יעקב - Neve Ya'akov - 1 0 100 2,860 קרית קמניץ Kiryat Kamenetz 0113 נווה יעקב )דרום( - Neve Ya'akov (south) - 6 1 99 3,710 רח' הרב פניז'ל, ,.Harav Fenigel St מתנ"ס community center 0114 נווה יעקב )מרכז( - Neve Ya'akov (center) - 6 1 99 3,450 מבוא אדמונד פלג .Edmond Fleg St 0115 נווה יעקב )צפון( - 3,480 99 1 6 Neve Ya'akov (north) - Meir Balaban St. רח' מאיר בלבן 0116 נווה יעקב )מערב( - 4,820 97 3 9 Neve Ya'akov (west) - Abba Ahimeir St., רח' אבא אחימאיר, Moshe Sneh St. רח' משה סנה תת רובע 012 - פסגת זאב צפון Sub-quarter 012 - - 4 96 18,500 Pisgat Ze'ev north א"ס .S.A 0121 פסגת זאב צפון )מערב( Pisgat Ze'ev north (west) - 6 94 4,770 0122 פסגת זאב צפון )מזרח( - Pisgat Ze'ev north (east) - - 1 99 3,120 רח' נתיב המזלות .Netiv Hamazalot St 0123 -

The Struggle for Hegemony in Jerusalem Secular and Ultra-Orthodox Urban Politics

THE FLOERSHEIMER INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES The Struggle for Hegemony in Jerusalem Secular and Ultra-Orthodox Urban Politics Shlomo Hasson Jerusalem, October 2002 Translator: Yoram Navon Principal Editor: Shunamith Carin Preparation for Print: Ruth Lerner Printed by: Ahva Press, Ltd. ISSN 0792-6251 Publication No. 4/12e © 2002, The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies, Ltd. 9A Diskin Street, Jerusalem 96440 Israel Tel. 972-2-5666243; Fax. 972-2-5666252 [email protected] www.fips.org.il 2 About the Author Shlomo Hasson - Professor of Geography at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and deputy director of The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies. About the Research This book reviews the struggle for hegemony in Jerusalem between secular and ultra-orthodox (haredi) Jews. It examines the democratic deficit in urban politics formed by the rise of the haredi minority to power, and proposes ways to rectify this deficit. The study addresses the following questions: What are the characteristics of the urban democratic deficit? How did the haredi minority become a leading political force in the city? What are the implications of the democratic deficit from the perspective of the various cultural groups? What can be done in view of the fact that the non-haredi population is not only under-represented but also feels threatened and prejudiced by urban politics initiated by the city council? About the Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies In recent years the importance of policy-oriented research has been increasingly acknowledged. Dr. Stephen H. Floersheimer initiated the establishment of a research institute that would concentrate on studies of long- range policy issues. -

The Millenarist Settlement in Artas and Its Support Network in Britain And

The Millenarist The village of Artas, near Bethlehem, may be known for any one of three reasons: its Settlement in Artas location next to Solomon’s Pools, as the and its support object of Hilma Granqvist’s ethnographic inquiry into Palestinian village life, or, network in Britain more recently, as the site of the annual and North America, Lettuce Festival organized by the Artas Folkore Center since the mid-1990s. What 1845-1878 is less known is that Artas also was the first Falestin Naili Palestinian village to become the home of millenarist European and American settlers in the nineteenth century. Millenarism as the belief in the Second Coming of Christ and his thousand-year reign on earth is an ideology that has played an important role in shaping European and North American views of the Middle East. It continues to do so to this day, particularly in the United States, but also in some evangelical milieus in Europe.1 In the nineteenth century, European and North American millenarists founded several settlements in Palestine Artas village and the convent of Hortus conclusus, ca. 1940, Watson collection, that constitute an important element in Library of Congress. the entangled history of the Middle East, Jerusalem Quarterly 45 [ 43 ] Solomon's Pools, second half of the 19th century, photographer unknown, Library of Congress. Europe and North America. The settlement founded in the Artas valley is a particularly interesting example of millenarist ambitions and activities in nineteenth-century Palestine. John Meshullam, a Jewish convert to Anglicanism from London, was the founder of the settlement in the Artas valley that became the first school for manual labor designed for the Jews of Palestine. -

Excluded, for God's Sake: Gender Segregation in Public Space in Israel

The Israel Religious Action Center Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation in Public Space in Israel The Israel Religious Action Center Excluded, For God’s Sake: Gender Segregation in Public Space in Israel NOVEMBER 2010 Written by Attorney Ricky Shapira-Rosenberg Consultation Attorney Einat Hurvitz, Attorney Ruth Carmi, Attorney Orly Erez-Lihovski English translation: Shaul Vardi Special thanks to The Ford Israel Fund, Richard and Rhoda Goldman Fund, New Israel Fund, Stanley Gold and the Women of Reform Judaism © Israel Religious Action Center, Israel Movement for Progressive (Reform) Judaism Cover photo: Tomer Appelbaum, “Ha’aretz,” September 29, 2010 – copyright Ha’aretz Newspaper Ltd. ContEntS 7 Introduction 23 18. Segregation at the annual conference of the Puah Institute A. 23 19. Segregation at a performance at the Tel The Phenomenon of Gender Aviv Culture Palace Segregation – Factual Findings Segregation in private businesses Gender segregation in public places 25 20. Corner snack shop providing services: 25 21. Elevator in a banqueting hall 11 1. Gender segregation in buses 25 22. Grocery store 12 2. Segregation in HMO clinics in Jerusalem 25 23. Fairground 13 3. Segregation in the HMO clinics in Beit 26 24. Pizza parlor Shemesh Segregation on the sidewalk 13 4. Segregation of men and women in a post 27 25. Kerem Avraham office in the Bukharian neighborhood of 27 26. Mea Shearim Jerusalem 14 5. Establishing a “kosher” police station in Ashdod B. 14 6. Segregation on El Al flights An Analysis of the Jewish 14 7. Poalei Agudat Israel Bank runs men-only Religious Requirement for Gender convention Segregation and the Role of 15 8. -

ENCYCLOPAEDIA JUDAICA, Second Edition, Volume 11 Worship

jerusalem worship. Jerome also made various translations of the Books pecially in letter no. 108, a eulogy on the death of his friend of Judith and Tobit from an Aramaic version that has since Paula. In it, Jerome describes her travels in Palestine and takes disappeared and of the additions in the Greek translation of advantage of the opportunity to mention many biblical sites, Daniel. He did not regard as canonical works the Books of Ben describing their condition at the time. The letter that he wrote Sira and Baruch, the Epistle of Jeremy, the first two Books of after the death of Eustochium, the daughter of Paula, serves as the Maccabees, the third and fourth Books of Ezra, and the a supplement to this description. In his comprehensive com- additions to the Book of Esther in the Septuagint. The Latin mentaries on the books of the Bible, Jerome cites many Jewish translations of these works in present-day editions of the Vul- traditions concerning the location of sites mentioned in the gate are not from his pen. Bible. Some of his views are erroneous, however (such as his in Dan. 11:45, which ,( ּ ַ אַפדְ נ וֹ ) The translation of the Bible met with complaints from explanation of the word appadno conservative circles of the Catholic Church. His opponents he thought was a place-name). labeled him a falsifier and a profaner of God, claiming that Jerome was regularly in contact with Jews, but his atti- through his translations he had abrogated the sacred traditions tude toward them and the law of Israel was the one that was of the Church and followed the Jews: among other things, they prevalent among the members of the Church in his genera- invoked the story that the Septuagint had been translated in a tion. -

Cfje Palestine #Ajette

Cfje Palestine #ajette NO. 1373 THURSDAY, 16TH NOVEMBER, 1944 1101 CONTENTS Page ORDINANCES CONFIRMED Confirmation of Ordinances Nos. 10 and 19 of 1944 1103 GOVERNMENT NOTICES 1103 - ־ - - - - .Appointments, etc Medical Licence cancelled - - - - 1103 Intended Destruction of Court Records — Notice of 1103 1106 ־' - ־ - Postal Service with Prance Embarassing Postal Packets - 1106 Air Mail Service to Prisoners of War and Civilians interned in Germany - - 1106 Palestine Post Office Savings Bank Deposit Book lost 1106 State Domains to be let by Auction - - - - - 1106 Sale of State Domain - - - - - 1106 Adjudication of Contracts - - - 1107 Claims for Mutilated Currency Notes - - - 1107 1108 - . ' • - •:' ־ • ־ - Citation Orders Court Notice - - - - - 1109 RETURNS Revenue and Expenditure Account for the Year ended 31st March, 1944, of the Jeru salem Water Supply - - - - - 1110 Balance Sheet as at 31st March, 1944, of the Jerusalem Water Supply - 1112 Summary of Receipts and Payments for the Year ended 31st March, 1944, of the Municipal Corporation of Jerusalem - _ _ 1114 Statement of Cash Assets and Liabilities as at 31st March, 1944, of the Municipal Corporation of Jerusalem _____ 1115 Loans Statement as at 31st March, 1944, of the Municipal Corporation of Jerusalem 1116 Quarantine and Infectious Diseases Summary - 1117 NOTICES REGARDING COOPERATIVE SOCIETIES, BANKRUPTCIES, REGISTRATION OF PARTNERSHIPS, ETC. _--____ 1117 CORRIGENDA - - - . - 1128 SUPPLEMENT No. 2. The following subsidiary legislation is published in Supplement No. 2 tchich forms part of this Gazette: — Defence (Water Distribution) Regulations, 1944, under the Emergency Powers (Colonial Defence) Order in Council, 1939, and the Emergency Powers (Defence) Act, 1939 ------ !157 Defence (Emergency Control of Motor Vehicles) (Amendment) Regulations, 1944, under the Emergency Powers (Defence) Acts, 1939 and 1940 - 1162 Defence (Protected Places) Order (No. -

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research JERUSALEM FACTS and TRENDS

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research JERUSALEM FACTS AND TRENDS Michal Korach, Maya Choshen Board of Directors Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research Dan Halperin, Chairman of the Board Ora Ahimeir Avraham Asheri Prof. Nava Ben-Zvi David Brodet Ruth Cheshin Raanan Dinur Prof. Hanoch Gutfreund Dr. Ariel Halperin Amb. Sallai Meridor Gil Rivosh Dr. Ehud Shapira Anat Tzur Lior Schillat, Director General Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2021 The State of the City and Changing Trends Michal Korach, Maya Choshen Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research 2021 This publication was made possible through the generous support of our partners: The Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research | Publication no. 564 Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2021 Michal Korach, Dr. Maya Choshen Assistance in Preparing this Publication: Omer Yaniv, Netta Haddad, Murad Natsheh,Yair Assaf-Shapira Graphic Design: Yael Shaulski Translation from Hebrew to English: Merav Datan © 2021, The Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., 9218604 Jerusalem www.jerusaleminstitute.org.il/en www.jerusaleminstitute.org.il Table of Contents About the Authors 8 Preface 9 Area Area 12 Population Population size 16 Geographical distribution 19 Population growth 22 Households 25 Population age 26 Marital status 32 Nature of religious identification 33 Socio-economic status 35 Metropolitan Jerusalem 41 Sources of Sources of population growth 48 Population Births 49 Mortality 51 Growth Natural increase 53 Aliya (Jewish immigration) 54 Internal migration 58 Migration -

Jerusalem: Facts and Trends

JE R U S A L E M JERUSALEM INSTITUTE : F FOR ISRAEL STUDIES A C T Jerusalem: Facts and Trends oers a concise, up-to-date picture of the S A N current state of aairs in the city as well as trends in a wide range of D T R areas: population, employment, education, tourism, construction, E N D and more. S The primary source for the data presented here is The Statistical 2014 Yearbook of Jerusalem, which is published annually by the Jerusalem JERUSALEM: FACTS AND TRENDS Institute for Israel Studies and the Municipality of Jerusalem, with the support of the Jerusalem Development Authority (JDA) and the Leichtag Family Foundation (United States). Michal Choshen, Korach Maya The Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies (JIIS), founded in 1978, Maya Choshen, Michal Korach is a non-prot institute for policy studies. The mission of JIIS is to create a database, analyze trends, explore alternatives, and present policy recommendations aimed at improving decision-making processes and inuencing policymaking for the benet of the general public. The main research areas of JIIS are the following: Jerusalem studies in the urban, demographic, social, economic, physical, and geopolitical elds of study; Policy studies on environmental issues and sustainability; Policy studies on growth and innovation; The study of ultra-orthodox society. Jerusalem Institute 2014 for Israel Studies The Hay Elyachar House 20 Radak St., Jerusalem 9218604 Tel.: +972-2-563-0175 Fax: +972-2-563-9814 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jiis.org 438 Board of Directors Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies Dan Halperin, Chairman of the Board Avraham Asheri David Brodet Ruth Cheshin Prof. -

LITERATURA MUNDO-Tomo 6 Pagfinal.Pdf

LITERATURA MUNDO-Tomo 6_PAGVALIDO.indd 1 12/06/20 17:18 LITERATURA MUNDO-Tomo 6_PAGVALIDO.indd 2 12/06/20 17:18 literatura‑mundocomparada: perspectivasemportuguês ‑ i i i ‑ pelotejovai‑separaomundo (volume6) LITERATURA MUNDO-Tomo 6_PAGVALIDO.indd 3 12/06/20 17:18 LITERATURA MUNDO-Tomo 6_PAGVALIDO.indd 4 12/06/20 17:18 literatura‑mundocomparada perspectivasemportuguês coordenaçãogeral:helenacarvalhãobuescu PARTEIII coordenaçãocientífica: helenacarvalhãobuescu simãovalente lisboa tinta‑da‑china MMXX LITERATURA MUNDO-Tomo 6_PAGVALIDO.indd 5 12/06/20 17:18 Parceirosinstitucionais: Apoios: Este trabalho é financiado por fundos nacionais através da FCT — Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., no âmbito do projeto HUIDB/00509/2020. © 2020, Centro de Estudos Comparatistas Este volume reproduz da Universidade de Lisboa os textos fixados nas edições e Edições tinta ‑da ‑china, Lda. consultadas, identificadas Rua Francisco Ferrer, 6 A | 1500 ‑461 Lisboa junto a cada texto. 21 726 90 28/29 | [email protected] www.tintadachina.pt Título: Literatura‑MundoComparada:Perspectivasemportuguês III—PeloTejoVai‑separaoMundo(Volume 6) CoordenaçãoGeral: Helena Carvalhão Buescu CoordenaçãoCientíficadeIII — Pelo Tejo Vai ‑se para 0 Mundo: Helena Carvalhão Buescu e Simão Valente CoordenaçãoExecutivade III — Pelo Tejo Vai ‑se para 0 Mundo: Amândio Reis, Bernardo Diniz Ferreira, Camila Seixas e Sousa, Francisco Carlos Marques, Gonçalo Cordeiro, João M.P. Gabriel, Marta Rosa, Rafael Esteves Martins Composição: -

9969.Ch01.Pdf

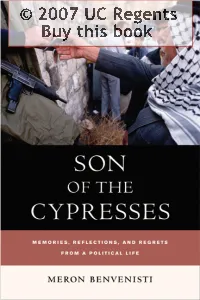

© 2007 UC Regents Buy this book University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Benvenisti, Meron, 1934–. Memories, reflections, and regrets from a political life / Meron Benvenisti, translated by Maxine Kaufman-Lacusta in consultation with Michael Kaufman-Lacusta p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn-13: 978–0-520–23825–1 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Israel—Politics and government—20th century. 2. Arab-Israeli conflict—Influence. 3. Arab- Israeli conflict—1993—Peace. 4. Israel—Ethnic relations. 5. Benvenisti, David. 6. Jews—Israel— Biography. 7. Sephardim—Israel—Biography. I. Title. DS126.995.B46 2006 956.9405092—dc22 2006032386 Manufactured in the United States of America 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 10 987654321 This book is printed on New Leaf EcoBook 50, a 100% recycled fiber of which 50% is de-inked post- consumer waste, processed chlorine-free. EcoBook 50 is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of ansi/astm d5634–01 (Permanence of Paper). Contents 1.A Founding Father 1 2.Delayed Filial Rebellion 32 3. Jerusalemites 57 4.“The Ceremony of Innocence Is Drowned . -

In the Land of Oz: a Tribute to Amos Oz

In the Land of Oz: A Tribute to Amos Oz Rachel Korazim I. In The Land of Israel 1 1. Thank God for His Daily Blessings 1 2. The Insult and the Fury 3 3. An Argument on Life and Death (A) 4 II. A Tale of Love and Darkness 6 4. Home – Jerusalem 6 5. Homeland – Vilna 7 6. Remaking the Home 9 7. Home in Hulda 11 III. The Same Sea 12 8. A Cat 12 9. Back in Bat Yam his Father Upbraids him 12 10. But his Mother Defends Him 12 11. No Butterflies and No Tortoise 13 12. Ditta Offers 16 13. Jews and Words 17 CLP Summer 2019 I. In The Land of Israel 1. Thank God for His Daily Blessings IN THE GEULAH QUARTER of Jerusalem, on Rabbi Meir Street, imprinted on one of the metal sewer covers is the English inscription “City of Westminster”—a reminder of the British Mandate in Palestine. The grocery store that was here forty years ago is still here. A new man sits there and studies Scriptures. It is after the High Holy Days: in Geulah, in Achvah, in Kerem Avraham, and in Mekor Baruch, the tatters of the flimsy booths built for the Feast of Tabernacles are still visible in the yards. Their greenery has faded and turned gray. There is a chill in the air. From porch to porch, the entire width of the alleyways, stretch laundry lines with white and colored clothes: these are the eternal morning blossoms of the neighborhood in which I grew up. -

Jerusalem, Producedannuallybythejerusaleminstituteforpolicyresearch

Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research The Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research (formerly the Jerusalem Institute 2016 for Israel Studies) is the leading institute in Israel for the study of Jerusalem’s JERUSALEM complex reality and unique social fabric. Established in 1978, the Institute focuses on the unique challenges facing Jerusalem in our time and provides extensive, in-depth knowledge for policy makers, academia, and the general public. FACTS AND TRENDS The work of the Institute spans all aspects of the city: physical and urban planning, social and demographic issues, economic and environmental Maya Choshen, Michal Korach, Dafna Shemer challenges, and questions arising from the geo-political status of Jerusalem. AND TRENDS JERUSALEM FACTS Its many years of multi-disciplinary work have afforded the Institute a unique perspective that allows it to expand its research and address complex challenges confronting Israeli society in a comprehensive manner. These challenges include urban, social, and strategic issues; environmental and sustainability challenges; and innovation and financing. Jerusalem: Facts and Trends provides a concise, up-to-date picture of the current state of affairs and trends of change in the city across a wide range of issues: population, employment, education, tourism, construction, and other areas. The main source of data for the publication is The Statistical Yearbook of Jerusalem, produced annually by the Jerusalem Institute for Policy Research. M. Choshen, M. Korach, D. Shemer M. Choshen, Korach, 461 2016 מכון ירושלים JERUSALEM למחקרי מדיניות Jerusalem Institute for Policy Reaserch INSTITUTE FOR POLICY 20 Radak st., Jerusalem 9218604 Tel +972-2-563-0175 Fax +972-2-5639814 Email [email protected] WWW.JIIS.ORG RESEARCH JERUSALEM INSTITUTE FOR POLICY RESEARCH Jerusalem: Facts and Trends 2016 The State of the City and Changing Trends Maya Choshen, Michal Korach, Dafna Shemer Jerusalem, 2016 PUBLICATION NO.