Settler-Colonialism, Memoricide and Indigenous Toponymic Memory: the Appropriation of Palestini- an Place Names by the Israeli State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palestine (5A3ette

XLbe Palestine (5a3ette Ipubltebeb b^ Hutbority No. 632 THURSDAY, 24TH SEPTEMBER, 1936 949 CONTENTS Page BILL PUBLISHED FOR INFORMATION ־ Pensions (Palestine Gendarmerie) Ordinance, 1936 - - 951 ORDINANCES CONFIRMED ־ - ־ Confirmation of Ordinances Nos. 44 and 57 of 1936 953 GOVERNMENT NOTICES Appointments, etc. - 953 Obituary ------ 954 Sittings of Court of Criminal Assize - 954 Sale of State Domain in Tiberias - - - - 955 Augmented Air Mail Service to Iraq, Iran and Iranian Gulf Ports - - 955 Tender and Adjudication of Contract - 956 Citation Orders - - - - - 956 Bankruptcy 957 EETURNS Quarantine and Infectious Diseases Summary - 95V Financial Statement at the 31st May, 1936 - - - - 958 Statement of Assets and Liabilities at the 31st May, 1936 - - - 960 Persons entering and leaving Palestine during August, 1936 - - 962 Persons changing their Names - 964 REGISTRATION OF CO-OPERATIVE SOCIETIES, COMPANIES, PARTNERSHIPS, ETC. - 965 CORRIGENDA - - - - .958 SUPPLEMENT No. 2. The following subsidiary legislation is published in Supplement No. 2 which forms part of this Gazette:— Court Fees (Amendment) Rules, 1936, under the Courts Ordinances, 1924-1935, and the ־ - - Magistrates' Courts Jurisdiction Ordinance, 1935 1119 Tariffs for the Transport of Goods under the Government Railways Ordinance, 1936 1120 {Continued) PRICE 30 MILS. CONTENTS {Continued) Page Curfew Order in respect of certain Areas within the Jerusalem District, under the ׳ Emergency Regulations, 1936 - - - 1122 Curfew Orders in respect of the Railway Formations in the Northern District, under the Emergency Regulations, 1936 . 1123 Curfew Orders in respect of the Town Planning Area of Nablus, Jenin—Deir-Sharaf— Tulkarm—Qalqilia Road, Nablus—Jerusalem Road and Municipal Areas of Acre, Jenin and Tulkarm, under the Emergency Regulations, 1936 - 1124 Rules under the Forests Ordinance, 1926, regarding the Forest Ranger at Zikhron Ya'aqov ------ !127 Notice under the Customs Ordinance, 1929, approving a General Bonded Warehouse ־ at the Levant Fair Grounds, Tel Aviv 1127 Order No. -

Fortid0308 Komplett.Indd

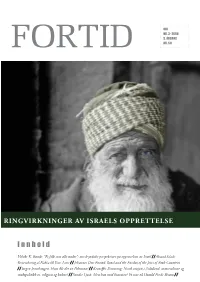

UIO NR. 3- 2008 5. ÅRGANG KR. 50 RINGVIRKNINGER AV ISRAELS OPPRETTELSE Innhold Vibeke K. Banik: ”Et folk som alle andre”: norsk-jødiske perspektiver på opprettelsen av Israel / / Ahmad Sa’adi: Remembering al-Nakba 60 Years Later / / Johannes Due Enstad: Israel and the Exodus of the Jews of Arab Countries / / Jørgen Jensehaugen: Hvor ble det av Palestina? / / Kristoffer Dannevig: Norsk misjon i Zululand: materialisme og maktpolitikk vs. religion og kultur? / / Sondre Ljoså: Men hva med historien? Et svar til Harald Frode Skram / / ISSN: 1504-1913 TRYKKERI: Allkopi REDAKTØR: Johannes Due Enstad og Anette Wilhelmsen REDAKSJONEN: Kristian Hunskaar, Martin Austnes, Mari Salberg, Øystein Idsø Viken, Stig Hosteland, Maria Halle, Olav Bogen, Marie Lund Alveberg, Marthe Glad Munch-Møller, Tor Gunnar Jensen og Steinar Skjeggedal ILLUSTRASJON OG GRAFISK UTFORMING: Forsideillustrasjon: Arabisk jøde fra Yemen. Mellom 1898 og 1914. Fotograf: American Colony (Jerusalem), Photo dept. Fotografi et er en del av G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, og er fritt tilgjengelig via commons.wikimedia.org. NB! Utsnitt. Svart/hvitt-fotografi et er delvis fargelagt. Forsidelayout og sidetegning: Alexander Worren (cover) og Trine Suphammer (sidetegning). KONTAKTTELEFON: 971 37 554 (Johannes Due Enstad) og 481 99 592 (Anette Wilhelmsen) E-POST: [email protected] NETTSIDE: www.fortid.no KONTAKTADRESSE: Universitetet i Oslo, IAKH, Fortid, Pb. 1008 Blindern, 0315 Oslo Fortid er medlem av tidsskriftforeningen, se www.tidsskriftforeningen.no Fortid utgis med støtte fra Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie ved Universitetet i Oslo, SiO og Norsk kulturråd Innholdsfortegnelse Fortid nr. 3 - 2008 5 LEDER 7 KORTTEKSTER ARTIKLER 12 ”Et folk som alle andre”: norsk-jødiske perspektiver på opprettelsen av Israel Vibeke K. -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Science in Archaeology: a Review Author(S): Patrick E

Science in Archaeology: A Review Author(s): Patrick E. McGovern, Thomas L. Sever, J. Wilson Myers, Eleanor Emlen Myers, Bruce Bevan, Naomi F. Miller, S. Bottema, Hitomi Hongo, Richard H. Meadow, Peter Ian Kuniholm, S. G. E. Bowman, M. N. Leese, R. E. M. Hedges, Frederick R. Matson, Ian C. Freestone, Sarah J. Vaughan, Julian Henderson, Pamela B. Vandiver, Charles S. Tumosa, Curt W. Beck, Patricia Smith, A. M. Child, A. M. Pollard, Ingolf Thuesen, Catherine Sease Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 99, No. 1 (Jan., 1995), pp. 79-142 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/506880 Accessed: 16/07/2009 14:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aia. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. -

Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects Sociology and Anthropology 1998 Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel Sarah VanSickle '98 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/socanth_honproj Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation VanSickle '98, Sarah, "Trade and Commerce at Sepphoris, Israel" (1998). Honors Projects. 19. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/socanth_honproj/19 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by Faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Trade and Commerce At Sepphoris, Israel Sarah VanSickle 1998 Honors Research Dr. Dennis E. Groh, Advisor I Introduction Trade patterns in the Near East are the subject of conflicting interpretations. Researchers debate whether Galilean cities utilized trade routes along the Sea of Galilee and the Mediterranean or were self-sufficient, with little access to trade. An analysis of material culture found at specific sites can most efficiently determine the extent of trade in the region. If commerce is extensive, a significant assemblage of foreign goods will be found; an overwhelming majority of provincial artifacts will suggest minimal trade. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

Palestine About the Author

PALESTINE ABOUT THE AUTHOR Professor Nur Masalha is a Palestinian historian and a member of the Centre for Palestine Studies, SOAS, University of London. He is also editor of the Journal of Holy Land and Palestine Studies. His books include Expulsion of the Palestinians (1992); A Land Without a People (1997); The Politics of Denial (2003); The Bible and Zionism (Zed 2007) and The Pales- tine Nakba (Zed 2012). PALESTINE A FOUR THOUSAND YEAR HISTORY NUR MASALHA Palestine: A Four Thousand Year History was first published in 2018 by Zed Books Ltd, The Foundry, 17 Oval Way, London SE11 5RR, UK. www.zedbooks.net Copyright © Nur Masalha 2018. The right of Nur Masalha to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988. Typeset in Adobe Garamond Pro by seagulls.net Index by Nur Masalha Cover design © De Agostini Picture Library/Getty All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Zed Books Ltd. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑272‑7 hb ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑274‑1 pdf ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑275‑8 epub ISBN 978‑1‑78699‑276‑5 mobi CONTENTS Acknowledgments vii Introduction 1 1. The Philistines and Philistia as a distinct geo‑political entity: 55 Late Bronze Age to 500 BC 2. The conception of Palestine in Classical Antiquity and 71 during the Hellenistic Empires (500‒135 BC) 3. -

Note: the List Was Compiled by @Maathmusleh. It Is Possible That Some Tweeps Are Missing

Note: the list was compiled by @MaathMusleh. It is possible that some tweeps are missing. It is also possible that there are minor mistakes in the data, besides the missing data. If you locate any missing information or wrong data, please contact @MaathMusleh. Note: Data in the Original village/city column is linked to a page with information about it. Note: Twitter handlers are linked to the personal blog/site of the person Note: the list of each continent is arranged by the number of followers (top to bottom) Note: presence of tweeps on the list does not necessarily mean endorsement to their political views; it is simply a fact sheet list Palestinians on Twitter Worldwide (Arab World (122), Asia (1), Australia (6), Central & South America (13), Europe (27), North America (87), Palestine (335)) Twitter Handler Country City/Village/RC* Original Village/City Arab World TamimBarghouti Egypt Cairo DeirGhassaneh khanfarw Qatar Doha AlRama AzmiBishara Qatar Doha Nazareth MouridBarghouti Egypt Cairo DeirGhassaneh AlSwairky KSA Riyadh jamalrayyan Qatar Doha TulKarem YZaatreh Jordan Amman Jericho Samihtoukan Jordan Amman Nablus luluderaven Egypt Cairo AlJura film_head KSA Jeddah Moabuobeid UAE Dubai Yabad iyad_elbaghdadi UAE Dubai Yafa 88Mona88 Qatar Doha Jerusalem livefromgaza Qatar Doha Majdal-Asqalan AliDahmash Jordan Amman Lydd lubzi azizdalloul Qatar Doha Gaza City docjazzmusic UAE Dubai Ellar Ammouni UAE Dubai Shaab DaoudKuttab Jordan Amman Baraah8 KSA LinaWaheeb Jordan Amman EinKarem Rdooan Egypt Cairo Yousefalawnah Kuwait Kuwait Falasteeni -

Aspects of St Anna's Cult in Byzantium

ASPECTS OF ST ANNA’S CULT IN BYZANTIUM by EIRINI PANOU A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 Acknowledgments It is said that a PhD is a lonely work. However, this thesis, like any other one, would not have become reality without the contribution of a number of individuals and institutions. First of all of my academical mother, Leslie Brubaker, whose constant support, guidance and encouragement accompanied me through all the years of research. Of the National Scholarship Foundation of Greece ( I.K.Y.) with its financial help for the greatest part of my postgraduate studies. Of my father George, my mother Angeliki and my bother Nick for their psychological and financial support, and of my friends in Greece (Lily Athanatou, Maria Sourlatzi, Kanela Oikonomaki, Maria Lemoni) for being by my side in all my years of absence. Special thanks should also be addressed to Mary Cunningham for her comments on an early draft of this thesis and for providing me with unpublished material of her work. I would like also to express my gratitude to Marka Tomic Djuric who allowed me to use unpublished photographic material from her doctoral thesis. Special thanks should also be addressed to Kanela Oikonomaki whose expertise in Medieval Greek smoothened the translation of a number of texts, my brother Nick Panou for polishing my English, and to my colleagues (Polyvios Konis, Frouke Schrijver and Vera Andriopoulou) and my friends in Birmingham (especially Jane Myhre Trejo and Ola Pawlik) for the wonderful time we have had all these years. -

Rights in Principle – Rights in Practice, Revisiting the Role of International Law in Crafting Durable Solutions

Rights in Principle - Rights in Practice Revisiting the Role of International Law in Crafting Durable Solutions for Palestinian Refugees Terry Rempel, Editor BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights, Bethlehem RIGHTS IN PRINCIPLE - RIGHTS IN PRACTICE REVISITING THE ROLE OF InternatiONAL LAW IN CRAFTING DURABLE SOLUTIONS FOR PALESTINIAN REFUGEES Editor: Terry Rempel xiv 482 pages. 24 cm ISBN 978-9950-339-23-1 1- Palestinian Refugees 2– Palestinian Internally Displaced Persons 3- International Law 4– Land and Property Restitution 5- International Protection 6- Rights Based Approach 7- Peace Making 8- Public Participation HV640.5.P36R53 2009 Cover Photo: Snapshots from «Go and See Visits», South Africa, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Cyprus and Palestine (© BADIL) Copy edit: Venetia Rainey Design: BADIL Printing: Safad Advertising All rights reserved © BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights December 2009 P.O. Box 728 Bethlehem, Palestine Tel/Fax: +970 - 2 - 274 - 7346 Tel: +970 - 2 - 277 - 7086 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.badil.org iii CONTENTS Abbreviations ....................................................................................vii Contributors ......................................................................................ix Foreword ..........................................................................................xi Foreword .........................................................................................xiv Introduction ......................................................................................1 -

Second Memorandum Historical Survey of the Jewish Population in Palestine from the Fall of the Jewish State to the Beginning of Zionist Pioneering

SECOND MEMORANDUM HISTORICAL SURVEY OF THE JEWISH POPULATION IN PALESTINE FROM THE FALL OF THE JEWISH STATE TO THE BEGINNING OF ZIONIST PIONEERING. Chapter I: Under Roman and Byzantine Rule. Chapter II: Under Arab Rule. Chapter III: The Crusaders. Chapter IV: The Mamluk Period. Chapter V: Under Turkish Rule. CHAPTER I UNDER THE ROMAN AND BYZANTINE RULE. The vivid rhetoric of Josephus Flavius' Jewish Wars and the absence of sources accessible to Western scholars for the later periods, have combined to create an impression in the minds of many people that the fatal issue of the Roman-Jewish war of 66-70 C.E. did not only result in the destruction of the Temple and of the city of Jerusalem, but brought Jewish life in Palestine to a complete standstill by obliterating what remained of the nation. However, even a cursory glance at the Jewish Wars will show that the struggle cannot have been as destructive as is popularly supposed. As shown on map A, Josephus specifically names as destroyed, apart from Jerusalem, four towns out of nearly forty, three districts (toparchies) out of eleven, and five villages. Even in these cases the destruction cannot have been very thorough. Lydda and Jaffa were burnt down by Cestius (Wars II,18,10 and 19,1), yet Jaffa had to be destroyed again (Wars III.9,3), while Lydda apparently continued to exist and surrendered quietly to Vespasian (ib. IV,18,1). The case of Bethannabris and the other villages in the Jordan Valley is even more instructive; burnt down by Placidus (Wars IV.7,5) they continued to flourish in the Talmudic period and remained Jewish strongholds down to the last days of Byzantine power in Palestine, i.e.