The History of Whisky in Scotland, 1644 to 1823

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solgud the Professor He Professor He Professor Kur Gin Stark Vatten

“Where science meets art and art solves thirst.” – Erik Liedholm, Distiller Inspired by both Chef and Sommelier sensibilities, Wildwood Spirits Co. blends ‘farm to table’ and ‘vineyard to bottle’ to create distillates in a unique & distinctive ‘farm to distillery’ fashion. Wildwood Spirits Co. sources nearly all of its ingredients from local Washington State farms. Solgud Orange & Fennel Liqueur Swedish for Sun God, this liqueur sstartedtarted with an unusedunused orange fraction and built it from there. AdAdAddedAd ded to that base, fennel seed andandand cardamomcardamom.... TTTheThe Professor Is an IrishIrish----StyleStyle Whiskey made with Washington Winter Wheat andand MaltMalt.. Distilled three times before aging. Kur Gin “Best Gin in the World” Double Gold “Best in Show” New York World Wine & SpiritSpiritss Competition 2014, 20172017 Stark Vatten Vodka Stark Vatten is Swedish for “strong water” Gold Medal, San Francisco International Spirits Competition 2016 The Dark DoorDoor,, Single Barrel Washington Straight Bourbon Whiskey, Gold Medal, Berlin InterInternationalnational Spirits CompetitionCompetition 2018 Ginnocence, No Alcohol Gin Made from the same botanicles as your favorite Gin “Kur” Your garden meets your garden party “Gin“Gin----uinely”uinely” the best A 20% service charge is included on each checkcheck.. SeastarSeastar retains 100% of the service charge. Our professional service team receives industry leading compensation which includes wages commissions and benifitsbenifits.... BEER ON TAP Multiplayer IPA, 6.8% ABV Washington -

The Perceptual Categorisation of Blended and Single Malt Scotch Whiskies Barry C

Smith et al. Flavour (2017) 6:5 DOI 10.1186/s13411-017-0056-x RESEARCH Open Access The perceptual categorisation of blended and single malt Scotch whiskies Barry C. Smith1*, Carole Sester2, Jordi Ballester3 and Ophelia Deroy1 Abstract Background: Although most Scotch whisky is blended from different casks, a firm distinction exists in the minds of consumers and in the marketing of Scotch between single malts and blended whiskies. Consumers are offered cultural, geographical and production reasons to treat Scotch whiskies as falling into the categories of blends and single malts. There are differences in the composition, method of distillation and origin of the two kinds of bottled spirits. But does this category distinction correspond to a perceptual difference detectable by whisky drinkers? Do experts and novices show differences in their perceptual sensitivities to the distinction between blends and single malts? To test the sensory basis of this distinction, we conducted a series of blind tasting experiments in three countries with different levels of familiarity with the blends versus single malts distinction (the UK, the USA and France). In each country, expert and novice participants had to perform a free sorting task on nine whiskies (four blends, four single malts, one single grain, plus one repeat) first by olfaction, then by tasting. Results: Overall, no reliable perceptual distinction was revealed in the tasting condition between blends and single malts by experts or novices when asked to group whiskies according to their similarities and differences. There was nonetheless a clear effect of expertise, with experts showing a more reliable classification of the repeat sample. -

ROBERT BURNS and PASTORAL This Page Intentionally Left Blank Robert Burns and Pastoral

ROBERT BURNS AND PASTORAL This page intentionally left blank Robert Burns and Pastoral Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland NIGEL LEASK 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX26DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York # Nigel Leask 2010 The moral rights of the author have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose the same condition on any acquirer British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Data available Typeset by SPI Publisher Services, Pondicherry, India Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn ISBN 978–0–19–957261–8 13579108642 In Memory of Joseph Macleod (1903–84), poet and broadcaster This page intentionally left blank Acknowledgements This book has been of long gestation. -

Cairngorms National Park Authority

CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY OUTCOME OF CALL-IN Call-in period: 1 March 2021 2021/0055/ADV to 2021/0067/DET 1. The CNPA has delegated responsibility to the CNPA Head Planner, to make Call-in decisions. PLANNING APPLICATION CALL-IN DECISIONS CNPA ref: 2021/0055/ADV Council ref: 21/00492/ADV Applicant: Caberfeidh Horizons Development 9 High Street, Kingussie, Highland location: Proposal: Erection of fascia sign Application Advertisement Consent type: Call in NO CALL-IN decision: Call in reason: N/A Planning Recent planning permission includes: History: 20/00638/FUL, Alterations and extension, Approved by LA Background Type 2: Advertisement consent applications; the application is therefore Analysis: not considered to raise issues of significance to the collective aims of the National Park. CNPA ref: 2021/0056/DET Council ref: 21/00094/FLL Applicant: Mr David Woodcock Development Sauchmore, Spittal Of Glenshee, Glenshee, Perth And Kinross location: Proposal: Alterations to holiday accommodation unit Application Detailed Planning Permission type: Call in NO CALL-IN decision: Call in reason: N/A Planning Recent planning permission includes: History: 20/01628/FLL, Alterations to dwellinghouse, Refused by LA Background Type 2: Householder developments – small developments that need Analysis: planning permission; the application is therefore not considered to raise issues of significance to the collective aims of the National Park. CNPA ref: 2021/0057/DET Council ref: 20/01695/FLL Applicant: Mr Daniel Price Development Land 1000 Metres -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Adrian Jahna Adrian Jahna Is from Avon Park and Works As a Sales Representative for BASF in the Southern Half of the State

WEDGWORTH LEADERSHIP INSTITUTE for Agriculture & Natural Resources newsletter• Director’s Dialogue- p.1-3 classX • Welcome to Swaziland...-p. 4-7 • Dam Sugar Cane- p. 8-11 Seminar XI • Swaziland Goodbyes...- p. 12-14 • Dairy, Sheep, & Berries So Sweet- p. 15-19 In This Issue: • Dancing Nights in Scotland Away- p. 20-23 • Cup of Joe with Dr. Joe Joyce- p. 24-25 • Coordinator’s Corner- p. 26-27 Reflect.Let’s Director’s Dialogue -Dr. Hannah Carter, Program Director “But if not for Wedgworth...” This is a familiar phrase that I love to have people complete who have been through the program. They finish the sentence with friendships they’ve formed, places they visited, experiences they would have never had or mind changing moments that altered their path. If you are reading this and have been through the program, how would you finish “But if not for Wedgworth…”? I am going to alter this though for the sake of sharing my experiences around our international seminar. “But if not for Dr. Eugene Trotter and Dr. Pete Hildebrand…” this class would not have had the most incredible international seminar—it was truly amazing for so many 1 different reasons—but it all leads back to these to issues around land and generational agriculture. two gentlemen who served as pioneers in their Through our relationship with Scotland’s equivalent respective fields and mentors to two “Yankee” grad of the Wedgworth program, we were able to visit students who found themselves at the University of the farms and enterprises of several Scottish Florida at the same time. -

126613742.23.Pdf

c,cV PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME XXV WARRENDER LETTERS 1935 from, ike, jxicUtre, in, ike, City. Chcomkers. Sdinburyk, WARRENDER LETTERS CORRESPONDENCE OF SIR GEORGE WARRENDER BT. LORD PROVOST OF EDINBURGH, AND MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR THE CITY, WITH RELATIVE PAPERS 1715 Transcribed by MARGUERITE WOOD PH.D., KEEPER OF THE BURGH RECORDS OF EDINBURGH Edited with an Introduction and Notes by WILLIAM KIRK DICKSON LL.D., ADVOCATE EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable Ltd. for the Scottish History Society 1935 Printed in Great Britain PREFACE The Letters printed in this volume are preserved in the archives of the City of Edinburgh. Most of them are either written by or addressed to Sir George Warrender, who was Lord Provost of Edinburgh from 1713 to 1715, and who in 1715 became Member of Parliament for the City. They are all either originals or contemporary copies. They were tied up in a bundle marked ‘ Letters relating to the Rebellion of 1715,’ and they all fall within that year. The most important subject with which they deal is the Jacobite Rising, but they also give us many side- lights on Edinburgh affairs, national politics, and the personages of the time. The Letters have been transcribed by Miss Marguerite Wood, Keeper of the Burgh Records, who recognised their exceptional interest. Miss Wood has placed her transcript at the disposal of the Scottish History Society. The Letters are now printed by permission of the Magistrates and Council, who have also granted permission to reproduce as a frontispiece to the volume the portrait of Sir George Warrender which in 1930 was presented to the City by his descendant, Sir Victor Warrender, Bt., M.P. -

Transport Scotland A9 Dualling Glen Garry to Dalwhinnie And

A9 Dualling Glen Garry to Dalwhinnie and Dalwhinnie to Crubenmore projects Draft Orders public exhibitions transport.gov.scot/a9dualling A9 Dualling draft Orders public exhibitions KEY Killiecrankie to Glen Garry Welcome Existing dualling Single carriageway to be upgraded Completed projects In December 2011, the Scottish Government announced its INVERNESS commitment to dual the A9 between Perth and Inverness by 2025. Tomatin to Moy Dalraddy to Slochd This public exhibition presents the draft Orders and Kincraig to Dalraddy AVIEMORE Crubenmore to Kincraig Environmental Statements for two of the eleven sections that KINGUSSIE Dalwhinnie make up the A9 Dualling Programme: to Crubenmore Glen Garry • Glen Garry to Dalwhinnie to Dalwhinnie BLAIR ATHOLL Dalwhinnie to Crubenmore. PITLOCHRY • Killiecrankie to Glen Garry Pitlochry to Killiecrankie Information on the following panels includes background on Tay Crossing to Ballinluig both projects and an explanation of the statutory processes Pass of Birnam to Tay Crossing Luncarty to Pass of Birnam that have been followed. PERTH Copies of the Environmental Statement Non-Technical A9 Perth to Inverness Dualling Programme – Summary for both projects are available for you to take away. overview of all 11 projects Transport Scotland staff, and their consultants, CH2M Fairhurst Joint Venture (CFJV), will be happy to assist you with any queries you may have. Further information can be found on the project websites: transport.gov.scot/project/a9-glen-garry-dalwhinnie transport.gov.scot/project/a9-dalwhinnie-crubenmore A9 Dualling draft Orders public exhibitions Introduction Design Manual for Roads and Bridges Process Killiecrankie to Glen Garry DMRB Stage 1 Identify the preferred route corridor Transport Scotland carries out a rigorous assessment process to establish the preferred option for a trunk road improvement project. -

Brand Listing for the State of Texas

BRAND LISTING FOR THE STATE OF TEXAS © 2016 Southern Glazer’s Wine & Spirits SOUTHERNGLAZERS.COM Bourbon/Whiskey A.H. Hirsch Carpenders Hibiki Michter’s South House Alberta Rye Moonshine Hirsch Nikka Stillhouse American Born Champion Imperial Blend Old Crow Sunnybrook Moonshine Corner Creek Ironroot Republic Old Fitzgerald Sweet Carolina Angel’s Envy Dant Bourbon Moonshine Old Grand Dad Ten High Bakers Bourbon Defiant Jacob’s Ghost Old Grand Dad Bond Tom Moore Balcones Devil’s Cut by Jim James Henderson Old Parr TW Samuels Basil Haydens Beam James Oliver Old Potrero TX Whiskey Bellows Bourbon Dickel Jefferson’s Old Taylor Very Old Barton Bellows Club E.H. Taylor Jim Beam Olde Bourbon West Cork Bernheim Elijah Craig JR Ewing Ole Smoky Moonshine Westland American Blood Oath Bourbon Evan Williams JTS Brown Parker’s Heritage Westward Straight Blue Lacy Everclear Kavalan Paul Jones WhistlePig Bone Bourbon Ezra Brooks Kentucky Beau Phillips Hot Stuff Whyte & Mackay Bonnie Rose Fighting Cock Kentucky Choice Pikesville Witherspoons Bookers Fitch’s Goat Kentucky Deluxe Private Cellar Woodstock Booze Box Four Roses Kentucky Tavern Rebel Reserve Woody Creek Rye Bourbon Deluxe Georgia Moon Kessler Rebel Yell Yamazaki Bowman Hakushu Knob Creek Red River Bourbon Bulleit Bourbon Hatfield & McCoy Larceny Red Stag by Jim Beam Burnside Bourbon Heaven Hill Bourbon Lock Stock & Barrel Redemption Rye Cabin Fever Henderson Maker’s Mark Ridgemont 1792 Cabin Still Henry McKenna Mattingly & Moore Royal Bourbon Calvert Extra Herman Marshall Mellow Seagram’s 7 -

Citizens' Forums, and Attitudes to Agriculture

CITIZENS’ FORUMS, AND ATTITUDES TO AGRICULTURE, ENVIRONMENT AND RURAL PRIORITIES RESEARCH REPORT BY MARK DIFFLEY CONSULTANCY AND RESEARCH AND INVOLVE 1 Citizens’ Forums and Attitudes to Agriculture, Environment and Rural Priorities June 2019 AUTHORS: Mark Diffley, Sanah Saeed Zubairi (Mark Diffley Consultancy and Research), Kaela Scott, Andreas Pavlou (Involve) 2 Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................ 5 Background and methodology ............................................................................... 5 Key findings and points of consideration ............................................................... 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 11 Background and aims .......................................................................................... 12 Methodology ........................................................................................................ 14 Quantitative data .............................................................................................. 15 Qualitative data ................................................................................................ 16 Principles................................................................................................................ 18 High quality food production............................................................................ 19 Perceptions of the value of -

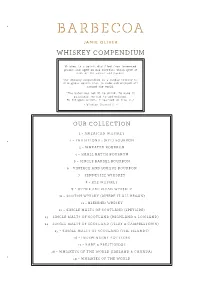

Whiskey Compendium

WHISKEY COMPENDIUM Whiskey is a spirit distilled from fermented grains and aged in oak barrels, which give it most of its colour and flavour. Our whiskey compendium is a humble tribute to this great spirit that is made and enjoyed all around the world. “The water was not fit to drink. To make it palatable, we had to add whiskey. By diligent effort, I learned to like it.” - Winston Churchill - OUR COLLECTION 1 – AMERICAN WHISKEY 2 – TRADITIONAL (RYE) BOURBON 3 – WHEATED BOURBON 4 – SMALL BATCH BOURBON 5 – SINGLE BARREL BOURBON 6 – VINTAGE AND UNIQUE BOURBON 7 – TENNESSEE WHISKEY 8 – RYE WHISKEY 9 – OTHER AMERICAN WHISKEY 10 – SCOTCH WHISKY (WHERE IT ALL BEGAN) 11 – BLENDED WHISKY 12 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (SPEYSIDE) 13 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (HIGHLAND & LOWLAND) 14 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (ISLAY & CAMPBELTOWN) 15 – SINGLE MALTS OF SCOTLAND (THE ISLANDS) 16 – INDEPENDENT BOTTLERS 17 – RARE & PRESTIGIOUS 18 – WHISKEYS OF THE WORLD (IRELAND & CANADA) 19 – WHISKIES OF THE WORLD AMERICAN WHISKEY – 1 – A SHORT HISTORY OF WHISKY OR WHISKEY? AMERICAN WHISKEY The Irish and Americans spell American whiskey is regulated by some whiskey with an “e”. The of the strictest laws of any spirit in Scots, Japanese and Canadians the world. Its heritage began when early spell whisky without. American settlers preserved their extra rye crops by distilling them. Although different to the barley they were used to in Europe, rye still made damn good whiskey. It was in the 18th Centu r y, EASY DISTILLATION when a quarter of a million Scottish and Irish immigrants arrived, that Distillation is a way to separate alcohol whiskey became serious business and from water, by boiling fermented grains the tax collectors were, of course, (called mash) and condensing its vapour. -

The Jacobites

THE JACOBITES Teacher’s Workshop Notes Timeline 1688 James II & VII overthrown; Stuarts go into exile 1701 James II & VII dies in France, his son becomes ‘James III & VIII’ in exile 1707 Act of Union between England and Scotland; union of the parliaments 1708 James attempts to invade Scotland but fails to land 1714 George I becomes King of Great Britain 1715 Major Jacobite uprising in Scotland and northern England; James lands in Scotland but the rising is defeated 1720 Charles Edward Stuart “Bonnie Prince Charlie” born in Rome 1734 Charlie attends siege of Gaeta, his only military experience, at just 14 years old 1744 Charles is invited to France to head a French invasion of Britain which is then called off; Charles decides not to return home and plans to raise an army in Scotland alone 1745 23 Jul Charles lands in Scotland with just a few supporters 19 Aug Charles raises the Standard at Glenfinnan; 1200 men join him 17 Sept Charles occupies Edinburgh 21 Sept Battle of Prestonpans, surprise Jacobite victory 1 Nov Jacobite Army invades England 5 Dec Council of War in Derby forces Charles to retreat against his will 1746 17 Jan Confused Jacobite victory at the Battle of Falkirk; retreat continues 16 Apr Jacobites defeat at the Battle of Culloden 20 Sept Charles finally escapes from Scotland 1766 James III & VIII dies in Rome; Charles calls himself ‘King Charles III’ in exile 1788 Charles dies in Rome, in the house in which he was born The Jacobites The name Jacobite comes from the Latin form of James, Jacobus, and is the term given to supporters of three generations of exiled Royal Stuarts: James II of England & VII of Scotland, James III & VIII, and Charles Edward Stuart.