Legislators' Patterns of Cooperation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC of CPI Report to 25Th Congress

Summary of the report of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Israel to the 25th Congress 31 May – 2 June 2007 Chapter 1: Corporate globalization and the struggle against it The globalization of capital and the rapid growth of modern industry, technology, information systems and media have been exploited by capital in an attempt to concentrate the control of resources, capital and wage labor. But this has also created the material basis for the international workers‟ solidarity exemplified in Marx and Engels‟ slogan: “Workers of the world, unite!” The adoption of the neo-liberal model has aggravated socioeconomic inequality, both within nations and between rich and poor countries, to an unprecedented level, while increasing the numbers of unemployed people, poor workers, women, children and older people living in miserable conditions. In the first decade of the 21st century, wealth continues to be concentrated in the hands of the two hundred largest multinational corporations – that is, in the hands of a few hundred billionaires – while the majority of humanity is forced to live in poverty, lacking basic necessities such as clean water, food, housing, schools and hospitals. The US administration continues to sabotage all attempts to reach meaningful international agreement on ways to curtail global warming (the greenhouse effect), thus endangering the very existence of the human race on Earth. The Bush Administration cynically exploits the concept of democracy in an attempt to conceal a cruel policy of conquest, destruction of social rights and impingement on democratic rights within the USA. “The war on terror” is the latest phase of the US attempt to create a “new world order”. -

Whose Side Are We On? Viewers’ Reactions to the Use of Irony in News Interviews

Pragmatics 25:2. 149-178 (2015) International Pragmatics Association DOI: 10.1075/prag.25.2.02hir WHOSE SIDE ARE WE ON? VIEWERS’ REACTIONS TO THE USE OF IRONY IN NEWS INTERVIEWS Galia Hirsch Abstract This research seeks to identify and analyze the reaction to irony in Israeli political news interviews, in view of the specific nature of this genre, which has been known to allow a certain level of adversarialness (Liebes et al. 2008; Blum-Kulka 1983; Weizman 2008; Clayman &Heritage 2002a and 2002b). Our intention was to examine whether the audience regards the use of irony as over-aggressive, and whether they believe interviewees regard it as such, in order to shed light on the potential consequences the use of indirect discourse patterns has for the interviewer. Based on Goffman's (1981) notion of footing, and on the concept of positioning as defined by Weizman (2008: 16), we focused on the audience's capacity to grasp the positioning and repositioning in the interaction as a possible influential factor in their reaction to the employment of irony. The research is based on two conceptual paradigms: Media studies and pragmatic studies of irony. The findings indicate that Israeli audiences tend to regard interviewers' employment of irony in political interviews as slightly hostile, and as such it is viewed as a possible threat to interviewees' face (Goffman 1967), but also as a legitimate and comprehensible tool, especially when the irony is accompanied by humor or mitigating non-verbal signs. Hence, the risk for the interviewer is not as great as we assumed. -

Middle East Peace Process Could Two Become One?

The Middle East peace process Could two become one? Israel’s right, frustrated Palestinians and assorted idealistic outsiders are talking of futures that do not feature a separate Palestinian state. It is a mistake Mar 16th 2013 | GAZA AND JERUSALEM | From the print edition IN 1942, as the Holocaust in Europe was entering its most horrific phase, a pacifist American rabbi called Judah Magnes helped found a political party in Palestine called Ihud. Not the best analogy Hebrew for unity, Ihud argued for a single binational state in the Holy Land to be shared by Jews and Arabs. Its efforts —and those of like-minded idealists—came to naught. Bitterly opposed to the partition of Palestine, Magnes died in 1948 just as the state of Israel—the naqba, or catastrophe, to Palestinians—was being born. Decades of strife were to follow. At the United Nations, in the White House and around the world, there is a strong belief that any solution ending that strife must be based on two separate states, with a mainly Jewish one called Israel sitting alongside a mainly Arab one called Palestine. The border between them would be based on the one that existed before the 1967 war—known as the “green line”—with some adjustments and land swaps to reflect the world as it is. Jerusalem would be a shared but divided capital. In the face of the manifold obstacles facing such a solution, however, something like Magnes’s one-state variant has been coming back into vogue, both in left-wing Western (and Jewish) circles and among a growing minority of Palestinians. -

Iron Domes: Desecuritization in the 2014 Israeli-Palestinian Conflict and the Battle for Identities

Iron Domes: Desecuritization in the 2014 Israeli-Palestinian Conflict and the Battle for Identities by Arel Jarus-Hakak A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts In Political Science- Political Theory Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2018 Arel Jarus-Hakak Abstract This thesis investigates the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; specifically, the empirical study centers on the 2014 military conflict. The objective of the study was to determine the optimal courses of action actors could take in their desecuritization efforts, within the Jewish Israeli context. This was achieved through the investigation of the intersubjective mechanisms that the Israeli government relied upon during this time, as well as the various strategies used by human rights organizations, Knesset members and other actors in their work to counter the securitization process. Theoretically, this work aims to bridge the gap between existing securitization literature, and critical theory, and further expand on existing literature. This thesis argues that desecuritizing agents should incorporate socio-cultural motifs in their arguments in front of Jewish Israeli audiences, as well as pivot towards international audiences to succeed in desecuritization. Table of Contents !"#$%&'$()*+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++*$* ,%-)(./"#01")'2*++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++*$$* -

The Energy Island: Israel Deals with Its Natural Gas Discoveries

POLICY PAPER Number 35 February 2015 The Energy Island: Israel Deals with its Natural Gas Discoveries NATAN SACHS TIM BOERSMA Acknowledgements This report, and the larger project of which it is a We are also very grateful to Ibraheem Egbaria, part, benefited greatly from the insight and assis- Ilan Suliman and Firash Qawasmi, who helped tance of a large number of people. facilitate our visit to the (East) Jerusalem District Electricity Company; to Ohad Reifen who helped For generosity with their time and insights we are facilitate interviews in Israel; and to Allison Good grateful to: Yossi Abu, CEO Delek Drilling; Con- for her helpful feedback on a draft of this paper. stantine Blyuz, Deputy Director for Economic & Strategic Issues, Israeli Ministry of National Infra- We would also like to thank our Brookings col- structures, Energy and Water Resources; Yael Co- leagues: Martin Indyk and Ted Piccone for support- hen Paran, CEO, Israel Energy Forum; Ariel Ezrahi, ing our work through the Foreign Policy Program’s Infrastructure (Energy) Adviser, Office of the Quar- Director’s Strategic Initiative Fund; Charles Ebin- tet Representative, Mr. Tony Blair; Michalis Firillas, ger, for his sage feedback on drafts and, along with Deputy Head of Mission, Consul, Embassy of the Tamara Wittes, for guiding us and providing won- Republic of Cyprus in Israel; Nurit Gal, Director, derful places within Brookings in which to work; Regulation and Electricity Division, Public Utilities Kemal Kirisci and Dan Arbell for their assistance, Authority of Israel; Dr. Gabi Golan, Deputy Gov- collaboration and multiple discussions throughout ernment Secretary, Office of the Prime Minister of the duration of this project; to Khaled Elgindy for the State of Israel; Mr. -

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev the Jacobblaustein Institutes For

Ben-Gurion University of the Negev The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research The Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies The Environmental Movement in Israel Strategic Analyses Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of "Master of Science" By: Shira Leon Zchout 12 November, 2013 Ben-Gurion University of the Negev The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research The Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies The Environmental Movement in Israel Strategic Analyses Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of "Master of Science" By: Shira Leon Zchout Under the Supervision of Professor Alon Tal Department of Desert Ecology / Environmental Studies Author's Signature Date November 11, 2013 Approved by the Supervisor Date: November 11, 2013. Approved by the Director of the School …………… Date ………….… The Environmental Movement in Israel Strategic Analyses Shira Leon Zchout This thesis is in partial fulfillment for the degree of Master of Science Ben-Gurion University of the Negev The Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research The Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies 2013 Abstract: In the face of environmental challenges, the Israeli environmental movement works to bring awareness to the public agenda, remove hazards and prevent future risks. This research examines the strategies applied by the Israeli ENGOs based on two theoretical models. First, it aims to characterize the relationship between resources and strategy, based upon the Resource Mobilization Theory . Second, the research examines the relationship between the state and Israel's environmental movement. Based on theories of Political Opportunities, the study assesses the most effective ways that civil society influence Israel's environmental policies. -

Outgoing Delegations—20Th Knesset

The Knesset Outgoing Delegations—20th Knesset Participation by the Director General of the Knesset in Events Marking 100 years of Democracy in Georgia Participants: Director General of the Knesset Albert Sakharovich Destination: Georgia Dates: 10–14 March 2019 Details: The Director General of the Knesset, Albert Sakharovich, was invited by his Georgian counterpart, Mr. Givi Mikandadze, to take part in a series of events marking the 100th anniversary of democracy in Georgia. During the visit, work meetings were held in Parliament, including a tour of the training center and a visit to an information and reception area for people with disabilities. In addition, a tour was held of the National Parliamentary Library of Georgia, which is housed in the parliament, and the Book Museum. Conference of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Mediterranean (PAM) in Belgrade Participants: MK Amir Peretz (Labor), MK Eitan Broshi (Labor) Destination: Belgrade, Serbia Dates: 20–24 February 2019 Details: MK Amir Peretz, the Knesset representative in the PAM, was elected by secret ballot as vice president of the organization with a large majority of 80% of the vote and was given the second slot after Italy. MK Peretz: "This is an important moment in strengthening the international standing of the Knesset in the international arena. It provides an opportunity to advance economic and political issues in a complex arena that includes representatives of the Mediterranean basin and representatives of Arab countries in our region." MK Peretz called on the organization to serve as an umbrella for bilateral talks, including between Israelis and Palestinians. Conference of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) Participants: MK Anat Berko (Likud) Destination: Vienna, Austria Dates: 20–23 February 2019 Details: The OSCE's Winter Meeting was held in February 2019 inVienna. -

State & Religion JPW Knesset Update

2018- Religion and state - JPW Knesset update - November - 11 11/12/18, 3:18 PM אם אינכם מצליחים לצפות במסר לחצו כאן State & Religion JPW Knesset Update Greetings to all our friends! This week the Ministerial Committee will discuss MK Yael German's (Yesh Atid} bill seeking to prohibit “conversion therapy” (trying to convert people’s sexuality) for minors. On Tuesday the State Control Committee will discuss the government's treatment of Israel's transgender community. Last Wednesday, in the aftermath of the Pittsburgh shooting, the Knesset held an emergency conference entitled "It's Time for Equality," calling for religious tolerance and closer ties with Diaspora Jewry, and appealing for Israel's recognition of the different Jewish denominations. The conference, held jointly with the Reform and Conservative movements, was the initiative of Deputy Minister MK Michael Oren (Kulanu), MK Nachman Shai (Zionist Union), MK Aliza Lavie (Yesh Atid), MK Rachel Azaria (Kulanu), MK Yael Cohen Paran (Zionist Union) and MK Mossi Raz (Meretz), and was attended by several public http://messages.responder.co.il/3516923/288244783/c3fddac147e891f0dc6f35f0d3292572/? Page 1 of 6 2018- Religion and state - JPW Knesset update - November - 11 11/12/18, 3:18 PM figures and more than 20 Knesset members from coalition and opposition parties including Likud, Meretz, Yisrael Beitenu, Zionist Union, Kulanu, Yesh Atid, and the Joint List. MK Nachman Shai: "We thought it only fitting that, at the initiative of the Reform and Conservative movements, the Knesset should take the time to highlight this issue, to make it heard, so as to find ways to repair the rifts and perhaps lead us to a new chapter in Israel's relationship with the various Jewish communities and streams. -

Religious Freedom in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Selected Issues a Report to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom

Religious Freedom in Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory: Selected Issues A Report to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom Palestine Works Editors Omar Yousef Shehabi Dr. Sara Husseini Hady Matar Emma Borden Contributors Jessica Boulet Dario D'Ambrosio Lojain al-Mouallimi John Pino Helena van Roosbroeck Andrew Udelsman Licensed under the Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Copyright © 2016 Palestine Works All rights reserved. ISBN: 0692688242 ISBN-13: 978-0692688243 Published by Palestine Works Inc. 1875 Connecticut Avenue NW, 10th Floor Washington, District of Columbia 20009 United States of America PALESTINE WORKS Palestine Works is a U.S.-based §501(c)(3) nonprofit organization founded in 2012 to promote Palestinian human rights and human development. Our vision is a Palestinian society that can enjoy the improved prospects and economic, social and political benefits of a strong economy, one powered by the development and deployment of Palestinian human capital. Our mission is to help realize this vision by engaging, developing and harnessing the expertise of young professionals through the creation of high-impact knowledge exchange opportunities, including internships, legal advocacy projects, conferences, publications and networking. CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1 Part One: Extending Ethnoreligious Control over Mandatory Palestine 2 Ethnoreligious Citizenship in the Israeli Control System 15 3 Maximalist Jewish Claims to -

Promoting Renewable Energy to Cope with Climate Change—Policy Discourse in Israel

sustainability Article Promoting Renewable Energy to Cope with Climate Change—Policy Discourse in Israel Avri Eitan The Advanced School for Environmental Studies, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 9190501, Israel; [email protected] Abstract: Evidence shows that global climate change is increasing over time, and requires the adop- tion of a variety of coping methods. As an alternative for conventional electricity systems, renewable energies are considered to be an important policy tool for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and therefore, they play an important role in climate change mitigation strategies. Renewable energies, however, may also play a crucial role in climate change adaptation strategies because they can reduce the vulnerability of energy systems to extreme events. The paper examines whether policy-makers in Israel tend to focus on mitigation strategies or on adaptation strategies in renewable energy policy discourse. The results indicate that despite Israel’s minor impact on global greenhouse gas emissions, policy-makers focus more on promoting renewable energies as a climate change mitigation strategy rather than an adaptation strategy. These findings shed light on the important role of international influence—which tends to emphasize mitigation over adaptation—in motivating the domestic policy discourse on renewable energy as a coping method with climate change. Keywords: climate change; renewable energy; mitigation; adaptation; climate change policy; en- ergy policy Citation: Eitan, A. Promoting Renewable Energy to Cope with 1. Introduction Climate Change—Policy Discourse in The world has experienced significant climate change in recent years, which scientists Israel. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3170. predict will only accelerate over time [1–3]. -

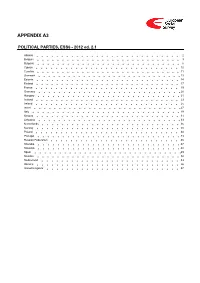

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

ISRAEL-PALESTINE After the 2014 War in Gaza GUE/NGL Delegation Visit to Palestine 4-7 September 2014

ISRAEL-PALESTINE After the 2014 war in Gaza GUE/NGL Delegation visit to Palestine 4-7 September 2014 1 Index 3 Introduction 4 GUE/NGL Delegation visit to Palestine - 4-7 September 2014 18 Motion for a Resolution on Israel-Palestine after the Gaza War and the Role of the EU 16 September 2014 22 Israel-Palestine after the Gaza War and the role of the EU. Plenary Debate. 17 September 2014 27 GUE/NGL backs the Russell Tribunal conclusion that the EU must act on Palestine 2 In summer 2014, Israel conducted a bloody 50-day military attack on the Gaza Strip which resulted in 2145 fatalities, including 581 children. Appalled and outraged, we immediately started planning a delegation to Palestine to show our solidarity with Palestinians in their on-going struggle against Israeli occupation. As part of our visit, we planned to enter Gaza to assess the situation on the ground first hand. This would have enabled us to relay information back to the European Parliament, giving greater weight to our demands for greater provision of EU humanitarian aid to Gaza and an end to the blockade and occupation. Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, our plans to visit Gaza were thwarted by the Israeli government’s refusal to grant us access; the justification given was that our visit to the region was ‘not directly con- cerned with the provision of humanitarian assistance’. This is beyond irony considering that the horrific and harrowing humanitarian situation in Gaza is a direct result of Israel’s bloody military attack on Gaza, and indeed Israel’s eight-year blockade of the region.