Editorial Comment on the Energy Situation : Prepared for The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Obama and Climate Policy Reform: a Continuing Education in American Politicking

OBAMA AND CLIMATE POLICY REFORM: A CONTINUING EDUCATION IN AMERICAN POLITICKING Colin Robertson The strange death of climate change legislation is a cautionary tale in American politicking. It is a reminder that the will and weight of the US presidency can be thwarted by the counterweights of regionalism, money and public indifference. Until we make a technological breakthrough, we face a “glorious mess” of federal regulation, litigation and continuing incrementalism at the state level. Canadians should pay heed. How America manages its grids and pipelines and how it prices carbon all have a direct effect on Canadian interests. We need to leverage our partnership to be, not an American clone, but “compatibly Canadian.” L’étrange abandon de toute réforme des lois sur le climat chez nos voisins du Sud en dit long sur les particularités de leurs mœurs politiques. Il vient ainsi rappeler que le contre-pouvoir des régions, les intérêts financiers et l’indifférence de l’opinion publique peuvent éclipser l’influence et la détermination du président. Seule une percée technologique pourrait y réguler le « bric-à-brac » actuel de règlements fédéraux, de litiges et de mesures disparates appliquées par les États. Le Canada doit surveiller la situation de près, car le mode de gestion des réseaux, des pipelines et du prix du carbone des Américains influe directement sur ses intérêts. Dans notre partenariat avec les États-Unis, nous devons faire valoir la « compatibilité » de nos politiques climatiques plutôt que de cloner la leur. n the sunny, uplit days following Barack Obama’s elec- In the public mind, “protecting the environment” had tion, reform of climate policy was perhaps the most surged in annual Pew survey rankings for 2006, 2007 and I anticipated promise in the agenda of hope that would 2008, with 56 percent of Americans identifying it as change not just America but the world. -

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series The Search for Value: Measuring the Company's Cost of Capital Michael C. Ehrhardt Managing Pension Plans: A Comprehensive Guide to Improving Plan Performance Dennis E. Logue and Jack S. Rader Efficient Asset Management: A Practical Guide to Stock Portfolio Optimization and Asset Allocation Richard O. Michaud Real Options: Managing Strategic Investment in an Uncertain World Martha Amram and Nalin Kulatilaka Beyond Greed and Fear: Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin Dividend Policy: Its Impact on Form Value Ronald C. Lease, Kose John, Avner Kalay, Uri Loewenstein, and Oded H. Sarig Value Based Management: The Corporate Response to Shareholder Revolution John D. Martin and J. William Petty Debt Management: A Practitioner's Guide John D. Finnerty and Douglas R. Emery Real Estate Investment Trusts: Structure, Performance, and Investment Opportunities Su Han Chan, John Erickson, and Ko Wang Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners Larry Harris Beyond Greed and Fear Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin 2002 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. -

Shell Whitepaper4 Copy

WHO ADVISED THE CANDIDATES ON ENERGY Introductio by Jared Anderson Energy was a major issue during the 2012 US Presidential campaign, with both candidates repeatedly touting the multiple benefits associated with increased domestic oil and natural gas output, the need for renewable energy and more. But there was virtually no coverage of the ocials who advised President Obama and Governor Romney on these issues. This exclusive AOL Energy series delves into who these ad- visors are, where they came from and the nature of their relationships with the candidates. With one hailing from business and the other rapidly rising through politics, their contrasting backgrounds and way of approaching impor- tant issues provides an insider look at where Obama and Romney received advice and information on a crucial elec- tion issue. Pag 1. Wh Obam an Romne Listene t o Energ By Elisa Wood It's hard to imagine two people less alike than Harold Hamm and Heather Zichal, the top energy advisers to the presidential candidates. Hamm, energy czar for Mitt Romney, is a billionaire oil man who rose to success with only a high school diploma. Raised as a sharecropper's son, he is now the 35th richest person in America. Heather Zichal, President Barack Obama's deputy assistant for energy and climate change, is the daughter of a medical doctor. She was an intern for the Sierra Club while at Rutgers University. After graduating, she soared up Washington's policy ranks to a top White House position in little over a decade. Who exactly are Hamm and Zichal? What influence do they wield? And what do energy and environmental insiders think about them? First Hamm Testifying before Congress on energy independence in September, Hamm said, "Good things flow from American oil and natural gas." And they certainly have for Hamm, age 66, who is founder, chairman and CEO of Continental Resources, an Oklahoma City independent oil and natural production company that has put Hamm on Forbes' list of wealthiest Americans and on Time Magazine's list of the most influential. -

From Czars to Commissars: Centralizing Policymaking Power in the White House

FROM CZARS TO COMMISSARS: CENTRALIZING POLICYMAKING POWER IN THE WHITE HOUSE Parnia Zahedi INTRODUCTION In the wake of the family separation crisis at the border in the summer of 2018, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer tweeted a proposal: the Trump Administration should “appoint a Czar to break thru the bureaucracy & get these kids out of limbo & back in their parents arms.”1 Seven years earlier, Senator John McCain used Twitter to complain President Obama had “more czars than the Romanovs,” a reference to the last Russian dynasty’s tyrannical emperors.2 Despite his high number of czars, President Obama was hardly the first president to employ the use of policy czars as a management tool to centralize White House policymaking power. This centralization has carried into the Trump Administration through both the use of czars and a “shadow cabinet” built of agency “watchdogs” that monitor cabinet secretaries for loyalty.3 From czars to shadow cabinets, the increasing influence of the President over administrative action has led to great controversy amongst Congress, the media, and the public. The czar label’s tyrannical roots4 reflect the central concern of presidents going outside of the Senate “Advice and Consent” process required by Article II of the Constitution to appoint powerful advisors without any accountability to Congress or the public.5 Existing academic literature focuses on this seeming constitutional conflict, with some scholars advocating for the elimination of czars, while others argue that the lack of advice and consent leads to policymaking that occurs “outside of the ordinary, Administrative Procedure Act (APA)-delimited structure of agencies.”6 This paper does not seek to further any constitutional arguments regarding czars, agreeing with scholarship that accepts the constitutionality of these presidential advisors as either 1 Chuck Schumer (@SenSchumer), TWITTER (June 24, 2018, 12:09 PM), https://twitter.com/senschumer/status/1010917833423970304?lang=en. -

59Th Annual Distinguished Service Award Harvey P. Eisen, BS BA

59th Annual Distinguished Service Award Harvey P. Eisen, BS BA '64 Chairman, CEO and Director, Wright Investors' Service Holdings, Inc. Chairman and Managing Partner; Bedford Oak Advisers, LLC Chairman and Director, GP Strategies Harvey P. Eisen is Chairman, CEO and Director of Wright Investors’ Service Holdings, Inc. (WISH), formerly National Patent Development Corporation. He has also served as Chairman of Bedford Oak Advisors, LLC, an investment partnership since 1998, and Chairman and Director of GP Strategies since 2004. He was previously Senior Vice President of Travelers, Inc. and held various executive positions with Primerica, SunAmerica Corp., and Integrated Resources Asset Management. Mr. Eisen was president and portfolio manager of Eisen Capital Management for 10 years. He began his career as an analyst with Stifel, Nicolaus & Co. and Wertheim. Mr. Eisen has served on the Strategic Development Board for the Trulaske College of Business, University of Missouri since 1995 where he established the first accredited course on the Warren Buffett Principles of Investing. He also serves on the Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences Advisory Board for Johns Hopkins University and is a member of the Carey Business School Board of Overseers and the Hopkins Parents Council. Mr. Eisen is widely recognized as one of the country’s leading portfolio managers. With over three decades of investment experience, he is often consulted by the national media for his expert views on all phases of the investment marketplace and is frequently quoted in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Pension World, U.S. News & World Report, Financial World and Business Week, among others. -

The American Czars Kevin Sholette

Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy Volume 20 Article 6 Issue 1 Fall 2010 The American Czars Kevin Sholette Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cjlpp Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Sholette, Kevin (2010) "The American Czars," Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy: Vol. 20: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cjlpp/vol20/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE THE AMERICAN CZARS Kevin Sholette* Over the last quarter-centurypresidents have appointed an increas- ing number of czars to try to maintain some control over the burgeoning administrativestate. The increasing appointment of czars has inevitably led to congressionalconcerns about the constitutionalityof the practice. Congressional indignation has been truly bipartisan, with both Demo- cratic Senator Russ Feingold and Independent Senator Joe Lieberman holding hearings on the issue and numerous Republican senators pub- licly criticizing the practice. The nature of the term czar is loaded with historical connotationsand emotive implications that have done a disser- vice to the academic analysis of the constitutionalissues. Any meaning- ful analysis must cut through the political and popular confusion and focus on the Constitution and case law at the heart of the issue. As one of the most problematic czars, the "Pay Czar," Kenneth Feinberg,pro- vides a good case study for how to apply the appropriate analysis. -

Democratic National Committee, 1/12/77

Democratic National Committee, 1/12/77 Folder Citation: Collection: Office of Staff Secretary; Series: 1976 Campaign Transition File; Folder: Democratic National Committee, 1/12/77; Container 1 To See Complete Finding Aid: http://www.jimmycarterlibrary.gov/library/findingaids/Staff_Secretary.pdf Talking Points 1. Democratic administratt6n taking over an economic and -bud~etary situation that is in bad shape. Economy: -8 % unemployment -recovery has sl~wed " ,. : ,J -virtually every economic forecast predicts that economic growth in 1977 will not be enough t,oreduce unemployment significantly , ':' "',, '. ' ' -world economy has also slowed---stronger countries (U.S., Germany, ,Japan) must take actions to stimulate, or else ' whole world in trouble . Budgets -Budget deficit in FY 1977 will amount to $60 billion, virtually all of which due to continuing recession II. Need to take strong. economic actions with-, four goalsl 1. Get private economy moving up in healthy self• sustaining recovery: restore sense of progress and confidence in American people. ~., ?~~ .11! / • ,,";.:." 2. At same time take direct;government actions to put people to work"dotng:U:seful' things. 3. Make a beginning on simplifying and reforming tax system. 4. Be prudent and careful about it so as not to over• commit---still ~hoot for balanced budget when economic recovery has taken full effect. III. Therefore need' a combination of measures. No one thing will do. -We have considered a number of different options and combinations -We have, at least in broad outline, tentatively identif.'ied·~~'.'..... the kinds of action which meet the four objectives ",-'-~~-:", -Would like to sketch this outline and get advice of the Congressional leaders ELECTROST[\TIC REPRODUCTION fJlADE fO fRESERW\TION PURPOSES I' IV. -

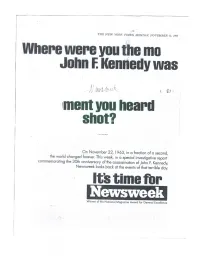

Its Time For

THE NEW YORK TIMES, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 1993 Where were you the mo John F. Kennedy was tur1/1!:-i z Iment you heard shot? b011,3,111. On November 22, 1963, in a fraction of a second, the world changed forever. This week, in a special investigative report commemorating the 30th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Newsweek looks back at the events of that terrible day. Its time for Newsweek. Winner of the National Magazine Award for General Excellence Newsweek Ir HO' 71:171 "_, .‘" It's Nut Whet YOu Think was in my third year of college, and I was walking with my friend, Alan Placa, now Monsignor Placa. Someone came up to us and said that President Kennedy had been shot. At first, we thought it was a joke or a wild report. Then, some- one else said it to us. We went to a radio nearby where we heard the news report. Then we went to I remember the day well. I was at my car and put on the radio We the office when I heard. I ran out sat in the car for over one hour just of my office into the hall - I wanted listening in shock because we io call out the news to everyone. I didn't wont to leave until they started to cry; I couldn't get the announced it, that he was actually words out, Everyone stayed con- dead " gregated in the halls for some Rudolph Giuliani time. We all wanted to be together Mayor Elect, City of New York with each other in our sorrow.' Ed Meyer Chairman/President and Chief Executive Officer Grey Advertising was leaving the Beverly Hills Post Office. -

Maggie-Mahar-Bull-A-History-Of-The

BULL! Ba history of the boom and bust, 1982–2004 maggie mahar To Raymond, who believes that everything is possible — Contents — Acknowledgments vii Prologue Henry Blodget xiii Introduction Chapter 1—The Market’s Cycles 3 Chapter 2—The People’s Market 17 Beginnings (1961–89) Chapter 3—The Stage Is Set 35 (1961–81) Chapter 4—The Curtain Rises 48 (1982–87) Chapter 5—Black Monday (1987–89) 61 iv Contents The Cast Assembles (1990–95) Chapter 6—The Gurus 81 Chapter 7—The Individual Investor 102 Chapter 8—Behind the Scenes, 123 in Washington The Media, Momentum, and Mutual Funds (1995–96) Chapter 9—The Media: CNBC Lays 153 Down the Rhythm Chapter 10—The Information Bomb 175 Chapter 11—AOL: A Case Study 193 Chapter 12—Mutual Funds: 203 Momentum versus Value Chapter 13—The Mutual Fund 217 Manager: Career Risk versus Investment Risk The New Economy (1996–98) Chapter 14—Abby Cohen Goes to 239 Washington; Alan Greenspan Gives a Speech Chapter 15—The Miracle of 254 Productivity The Final Run-Up (1998–2000) Chapter 16—“Fully Deluded 269 Earnings” Contents v Chapter 17—Following the Herd: 288 Dow 10,000 Chapter 18—The Last Bear Is Gored 304 Chapter 19—Insiders Sell; 317 the Water Rises A Final Accounting Chapter 20—Winners, Losers, and Scapegoats 333 (2000–03) Chapter 21—Looking Ahead: What 353 Financial Cycles Mean for the 21st-Century Investor Epilogue (2004–05) 387 Notes 397 Appendix 473 Index 481 about the author credits cover copyright about the publisher — Acknowledgments — More than a hundred people contributed to this book, sharing their expe- riences, their insights, and their knowledge. -

Journal of Applied Corporate Finance

VOLUME 31 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 2019 Journal of APPLIED CORPORATE FINANCE IN THIS ISSUE: Columbia Law School Symposium on Corporate Governance “Counter-Narratives”: On Corporate Purpose and Shareholder Value(s) Corporate 10 Session I: Corporate Purpose and Governance Colin Mayer, Oxford University; Ronald Gilson, Columbia and Stanford Law Schools; and Martin Purpose— Lipton, Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz LLP. 26 Session II: Capitalism and Social Insurance and EVA Jeffrey Gordon, Columbia Law School. Moderated by Merritt Fox, Columbia Law School. 32 Session III: Securities Law in Twenty-First Century America: Once More? A Conversation with SEC Commissioner Rob Jackson Robert Jackson, Commissioner, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Moderated by John Coffee, Columbia Law School. 44 Session IV: The Law, Corporate Governance, and Economic Justice Chief Justice Leo Strine, Delaware Supreme Court; Mark Roe, Harvard Law School; Jill Fisch, University of Pennsylvania Law School; and Bruce Kogut, Columbia Business School. Moderated by Eric Talley, Columbia Law School. 64 Session V: Macro Perspectives: Bigger Problems than Corporate Governance Bruce Greenwald and Edmund Phelps, Columbia Business School. Moderated by Joshua Mitts, Columbia Law School. 74 Is Managerial Myopia a Persistent Governance Problem? David J. Denis, University of Pittsburgh 81 The Case for Maximizing Long-Run Shareholder Value Diane Denis, University of Pittsburgh 90 A Tribute to Joel Stern Bennett Stewart, Institutional Shareholder Services 95 A Look Back at the Beginning of EVA and Value-Based Management: An Interview with Joel M. Stern Interviewed by Joseph T. Willett 103 EVA, Not EBITDA: A New Financial Paradigm for Private Equity Firms Bennett Stewart, Institutional Shareholder Services 116 Beyond EVA Gregory V. -

The Debate Over Selected Presidential Assistants and Advisors: Appointment, Accountability, and Congressional Oversight

The Debate Over Selected Presidential Assistants and Advisors: Appointment, Accountability, and Congressional Oversight Barbara L. Schwemle Analyst in American National Government Todd B. Tatelman Legislative Attorney Vivian S. Chu Legislative Attorney Henry B. Hogue Analyst in American National Government October 9, 2009 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R40856 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Selected Special Assistants and Advisors Summary A number of the appointments made by President Barack Obama to his Administration or by Cabinet Secretaries to their departments have been referred to, especially by the news media, as “czars.” For some, the term is being used to quickly convey an appointee’s title (e.g., climate “czar”) in shorthand. For others, it is being used to convey a sense that power is being centralized in the White House or certain entities. When used in the political science literature, the term generally refers to White House policy coordination or an intense focus by the appointee on an issue of great magnitude. Congress has taken note of these appointments; several Members have introduced legislation or sent letters to President Obama to express their concerns. Legislation introduced includes H.Amdt. 49 to H.R. 3170; H.R. 3226; H.R. 3569; H.Con.Res. 185; H.R. 3613; H.Res. 778; S.Amdt. 2440 to H.R. 2996; S.Amdt. 2498 to H.R. 2996; S.Amdt. 2548 to S.Amdt. 2440 to H.R. 2996; and S.Amdt. 2549 to H.R. 2996. One issue of interest to Congress may be whether some of these appointments (particularly some of those to the White House Office), made outside of the advice and consent process of the Senate, circumvent the Constitution. -

Obama's "Czars" for Domestic Policy and the Law of the White House Staff

Fordham Law Review Volume 79 Issue 6 Article 6 November 2011 Obama's "Czars" for Domestic Policy and the Law of the White House Staff Aaron J. Saiger Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Aaron J. Saiger, Obama's "Czars" for Domestic Policy and the Law of the White House Staff, 79 Fordham L. Rev. 2577 (2011). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol79/iss6/6 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. OBAMA’S “CZARS” FOR DOMESTIC POLICY AND THE LAW OF THE WHITE HOUSE STAFF Aaron J. Saiger* I. “MORE CZARS THAN THE ROMANOVS”1 Soon after the 2008 presidential election, President-Elect Barack Obama announced that he would simultaneously nominate ex-Senate majority leader Tom Daschle as Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) and appoint him to direct the Office of Health Reform, an office to be newly created within the White House. The latter position, notwithstanding its official title, was universally—if colloquially—dubbed health care “czar.”2 The czar job, not the Cabinet position, was the big news. It would make Daschle, the Washington Post breathlessly reported, “the first Cabinet secretary in decades to have an office in the West Wing.”3 Obama also named Lisa Jackson, who had earlier worked for the Enforcement Division of the U.S.