Economic and Financial...Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F:\RSS\Me\Society's Mathemarica

School of Social Sciences Economics Division University of Southampton Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK Discussion Papers in Economics and Econometrics Mathematics in the Statistical Society 1883-1933 John Aldrich No. 0919 This paper is available on our website http://www.southampton.ac.uk/socsci/economics/research/papers ISSN 0966-4246 Mathematics in the Statistical Society 1883-1933* John Aldrich Economics Division School of Social Sciences University of Southampton Southampton SO17 1BJ UK e-mail: [email protected] Abstract This paper considers the place of mathematical methods based on probability in the work of the London (later Royal) Statistical Society in the half-century 1883-1933. The end-points are chosen because mathematical work started to appear regularly in 1883 and 1933 saw the formation of the Industrial and Agricultural Research Section– to promote these particular applications was to encourage mathematical methods. In the period three movements are distinguished, associated with major figures in the history of mathematical statistics–F. Y. Edgeworth, Karl Pearson and R. A. Fisher. The first two movements were based on the conviction that the use of mathematical methods could transform the way the Society did its traditional work in economic/social statistics while the third movement was associated with an enlargement in the scope of statistics. The study tries to synthesise research based on the Society’s archives with research on the wider history of statistics. Key names : Arthur Bowley, F. Y. Edgeworth, R. A. Fisher, Egon Pearson, Karl Pearson, Ernest Snow, John Wishart, G. Udny Yule. Keywords : History of Statistics, Royal Statistical Society, mathematical methods. -

Social and Cultural Functions of the Local Press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900

Reading the local paper: Social and cultural functions of the local press in Preston, Lancashire, 1855-1900 by Andrew Hobbs A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire November 2010 ABSTRACT This thesis demonstrates that the most popular periodical genre of the second half of the nineteenth century was the provincial newspaper. Using evidence from news rooms, libraries, the trade press and oral history, it argues that the majority of readers (particularly working-class readers) preferred the local press, because of its faster delivery of news, and because of its local and localised content. Building on the work of Law and Potter, the thesis treats the provincial press as a national network and a national system, a structure which enabled it to offer a more effective news distribution service than metropolitan papers. Taking the town of Preston, Lancashire, as a case study, this thesis provides some background to the most popular local publications of the period, and uses the diaries of Preston journalist Anthony Hewitson as a case study of the career of a local reporter, editor and proprietor. Three examples of how the local press consciously promoted local identity are discussed: Hewitson’s remoulding of the Preston Chronicle, the same paper’s changing treatment of Lancashire dialect, and coverage of professional football. These case studies demonstrate some of the local press content that could not practically be provided by metropolitan publications. The ‘reading world’ of this provincial town is reconstructed, to reveal the historical circumstances in which newspapers and the local paper in particular were read. -

Apprentice Strikes in Twentieth Century UK Engineering and Shipbuilding*

Apprentice strikes in twentieth century UK engineering and shipbuilding* Paul Ryan Management Centre King’s College London November 2004 * Earlier versions of this paper were presented to the International Conference on the European History of Vocational Education and Training, University of Florence, the ESRC Seminar on Historical Developments, Aims and Values of VET, University of Westminster, and the annual conference of the British Universities Industrial Relations Association. I would like to thank Alan McKinlay and David Lyddon for their generous assistance, and Lucy Delap, Alan MacFarlane, Brian Peat, David Raffe, Alistair Reid and Keith Snell for comments and suggestions; the Engineering Employers’ Federation and the Department of Education and Skills for access to unpublished information; the staff of the Modern Records Centre, Warwick, the Mitchell Library, Glasgow, the Caird Library, Greenwich, and the Public Record Office, Kew, for assistance with archive materials; and the Nuffield Foundation and King’s College, Cambridge for financial support. 2 Abstract Between 1910 and 1970, apprentices in the engineering and shipbuilding industries launched nine strike movements, concentrated in Scotland and Lancashire. On average, the disputes lasted for more than five weeks, drawing in more than 15,000 young people for nearly two weeks apiece. Although the disputes were in essence unofficial, they complemented sector-wide negotiations by union officials. Two interpretations are considered: a political-social-cultural one, emphasising political motivation and youth socialisation, and an economics-industrial relations one, emphasising collective action and conflicting economic interests. Both interpretations prove relevant, with qualified priority to the economics-IR one. The apprentices’ actions influenced economic outcomes, including pay structures and training incentives, and thereby contributed to the decline of apprenticeship. -

History and Bibliography of American Newspapers 1690-1820

Additions and Corrections to History and Bibliography of American Newspapers 1690-1820 BY CLARENCE S. BRIGHAM FOREWORD HESE additions and corrections cover only certain T fields of the parent work which was published in 1947 in two volumes. All new titles are carefully entered and described, although only nine such titles have been dis- covered in the last thirteen years. Only unique issues acquired by libraries have been entered. Certain libraries, like the Library of Congress, the New York libraries, and especially the American Antiquarian Society, have acquired thousands of issues in the past few years, but these are all in long or complete files and generally are not mentioned. Libraries which have sent me lists of issues recently obtained should note this fact and not expect to find all copies listed. In a few cases long files acquired by libraries have been entered, on the assumption that they might contain a few issues not in the supposedly complete files in other libraries. New biographical facts concerning publishers, printers, and editors are entered. Frequently, the complete spellings of Christian names hitherto known only by initials are given. Important changes in the historical accounts of newspapers i6 AMERICAN ANTIQUARIAN SOCIETY [April, have been entered. Most of these changes have been ob- tained through correspondence, or by noting the record of additions in printed reports or bulletins of libraries. There has been no attempt to visit the many libraries to re-examine the various files. Microfilm reproductions issued by various libraries in the past few years have been noted, although not the many libraries purchasing such microfilm files. -

Angeli, Helen Rossetti, Collector Angeli-Dennis Collection Ca.1803-1964 4 M of Textual Records

Helen (Rossetti) Angeli - Imogene Dennis Collection An inventory of the papers of the Rossetti family including Christina G. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and William Michael Rossetti, as well as other persons who had a literary or personal connection with the Rossetti family In The Library of the University of British Columbia Special Collections Division Prepared by : George Brandak, September 1975 Jenn Roberts, June 2001 GENEOLOGICAL cw_T__O- THE ROssFTTl FAMILY Gaetano Polidori Dr . John Charlotte Frances Eliza Gabriele Rossetti Polidori Mary Lavinia Gabriele Charles Dante Rossetti Christina G. William M . Rossetti Maria Francesca (Dante Gabriel Rossetti) Rossetti Rossetti (did not marry) (did not marry) tr Elizabeth Bissal Lucy Madox Brown - Father. - Ford Madox Brown) i Brother - Oliver Madox Brown) Olive (Agresti) Helen (Angeli) Mary Arthur O l., v o-. Imogene Dennis Edward Dennis Table of Contents Collection Description . 1 Series Descriptions . .2 William Michael Rossetti . 2 Diaries . ...5 Manuscripts . .6 Financial Records . .7 Subject Files . ..7 Letters . 9 Miscellany . .15 Printed Material . 1 6 Christina Rossetti . .2 Manuscripts . .16 Letters . 16 Financial Records . .17 Interviews . ..17 Memorabilia . .17 Printed Material . 1 7 Dante Gabriel Rossetti . 2 Manuscripts . .17 Letters . 17 Notes . 24 Subject Files . .24 Documents . 25 Printed Material . 25 Miscellany . 25 Maria Francesca Rossetti . .. 2 Manuscripts . ...25 Letters . ... 26 Documents . 26 Miscellany . .... .26 Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti . 2 Diaries . .26 Manuscripts . .26 Letters . 26 Financial Records . ..27 Memorabilia . .. 27 Miscellany . .27 Rossetti, Lucy Madox (Brown) . .2 Letters . 27 Notes . 28 Documents . 28 Rossetti, Antonio . .. 2 Letters . .. 28 Rossetti, Isabella Pietrocola (Cole) . ... 3 Letters . ... 28 Rossetti, Mary . .. 3 Letters . .. 29 Agresti, Olivia (Rossetti) . -

NEW YORK TIMES BUILDING, 41 Park Row (Aka 39-43 Park Row and 147-151 Nassau Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 16, 1999, Designation List 303 LP-2031 (FORMER) NEW YORK TIMES BUILDING, 41 Park Row (aka 39-43 Park Row and 147-151 Nassau Street), Manhattan. Built 1888-89; George B. Post, architect; enlarged 1903-05, Robert Maynicke, architect. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 101 , Lot 2. On December 15, 1998, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the (former) New York Times Bu ilding and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 3). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Three witnesses, representing the New York Landmarks Conservancy, the Municipal Art Society, and the Historic Districts Council , spoke in favor of the designation. The hearing was re-opened on February 23 , 1999 for additional testimony from the owner, Pace University. Two representatives of Pace spoke, indicating that the university was not opposed to designation and looked forward to working with the Commission staff in regard to future plans for the building. The Commission has also received letters from Dr. Sarah Bradford Landau and Robert A.M. Stern in support of designation. This item had previously been heard for designation as an individual Landmark in 1966 (LP-0550) and in 1980 as part of the proposed Civic Center Hi storic District (LP-1125). Summary This sixteen-story office building, constructed as the home of the New York Times , is one of the last survivors of Newspaper Row, the center of newspaper publishing in New York City from the 1830s to the 1920s. -

Gladstone and the Bank of England: a Study in Mid-Victorian Finance, 1833-1866

GLADSTONE AND THE BANK OF ENGLAND: A STUDY IN MID-VICTORIAN FINANCE, 1833-1866 Patricia Caernarv en-Smith, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2007 APPROVED: Denis Paz, Major Professor Adrian Lewis, Committee Member and Chair of the Department of History Laura Stern, Committee Member Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Caernarven-Smith, Patricia. Gladstone and the Bank of England: A Study in Mid- Victorian Finance, 1833-1866. Master of Arts (History), May 2007, 378 pp., 11 tables, bibliography, 275 titles. The topic of this thesis is the confrontations between William Gladstone and the Bank of England. These confrontations have remained a mystery to authors who noted them, but have generally been ignored by others. This thesis demonstrates that Gladstone’s measures taken against the Bank were reasonable, intelligent, and important for the development of nineteenth-century British government finance. To accomplish this task, this thesis refutes the opinions of three twentieth-century authors who have claimed that many of Gladstone’s measures, as well as his reading, were irrational, ridiculous, and impolitic. My primary sources include the Gladstone Diaries, with special attention to a little-used source, Volume 14, the indexes to the Diaries. The day-to-day Diaries and the indexes show how much Gladstone read about financial matters, and suggest that his actions were based to a large extent upon his reading. In addition, I have used Hansard’s Parliamentary Debates and nineteenth-century periodicals and books on banking and finance to understand the political and economic debates of the time. -

AUTHOR Partisan Press Coverage of Anti-Abolitionist Violence

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 283 164 CS 210 565 AUTHOR Rutenbeck, Jeffrey B. TITLE Partisan Press Coverage of Anti-Abolitionist Violence--A Case Study of Status Quo Journalism. PUB DATE Aug 87 NOTE 32p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (70th, San Antonio, TX, August 1-4, 1987). PUB TYPE Reports - Research/Technical (143) -- Speeches/Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Blacks; Content Analysis; Media Research; *Newspapers; *News Reporting; Political Affiliation; *Press Opinion; United States History; Violence IDENTIFIERS *Abolitionism; Journalism History; Nineteenth Century ABSTRACT A study examined the conserving tendencies of the established political party press during the early stages of the antislavery movement. Eighteen partisan newspapers--from both northern and southern states--were examined for their coverage of the July 30, 1836, mob violence against James G. Birney and his Cincinnati "Philanthropist," and the November 7, 1837, shooting death of Elijah P. Lovejoy. It was hypothesized that newspapers most closely affiliated with those in political power, to preserve the status quo, would condemn the dissident press and deny the dissident editor's right to speak freely. For analysis, coverage was divided into three categories: (1) papers expressing original editorial views, (2) papers reprinting editorial views from otherpapers; and (3) papers with no coverage at all. The results indicated that all newspapers in the first category, with the exception of the New York "Evening Post," blamed the abolitionist editors for the violence, and the majority of newspapers in the second category reprinted material blaming the editors. The results also indicated that in both categories 1 and 2, the papers with the most demonstrable ties to established parties ignored freedom of the press issues and fervently blamed and opposed the abolitionist editors. -

Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University In

79I /f NIGERIAN MILITARY GOVERNMENT AND PRESS FREEDOM, 1966-79 THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Ehikioya Agboaye, B.A. Denton, Texas May, 1984 Agboaye, Ehikioya, Nigerian Military Government and Press Freedom, 1966-79. Master of Arts (Journalism), May, 1984, 3 tables, 111 pp., bibliography, 148 titles. The problem of this thesis is to examine the military- press relationship inNigeria from 1966 to 1979 and to determine whether activities of the military government contributed to violation of press freedom by prior restraint, postpublication censorship and penalization. Newspaper and magazine articles related to this study were analyzed. Interviews with some journalists and mili- tary personnel were also conducted. Materials collected show that the military violated some aspects of press freedom, but in most cases, however, journalists were free to criticize government activities. The judiciary prevented the military from arbitrarily using its power against the press. The findings show that although the military occasionally attempted suppressing the press, there are few instances that prove that journalists were denied press freedom. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES............ .P Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 Statement of the Problem Purpose of the Study Significant Questions Definition of Terms Review of the Literature Significance of the Study Limitations Methodology Organization II. PREMILITARY ERA,.... 1865-1966...18 . From Colonial to Indigenous Press The Press in the First Republic III. PRESS ACTIONS IN THE MILITARY'S EARLY YEARS 29 Before the Civil War The Nigeria-Biaf ran War and After IV. -

Mundella Papers Scope

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 6 - 9, MS 22 Title: Mundella Papers Scope: The correspondence and other papers of Anthony John Mundella, Liberal M.P. for Sheffield, including other related correspondence, 1861 to 1932. Dates: 1861-1932 (also Leader Family correspondence 1848-1890) Level: Fonds Extent: 23 boxes Name of creator: Anthony John Mundella Administrative / biographical history: The content of the papers is mainly political, and consists largely of the correspondence of Mundella, a prominent Liberal M.P. of the later 19th century who attained Cabinet rank. Also included in the collection are letters, not involving Mundella, of the family of Robert Leader, acquired by Mundella’s daughter Maria Theresa who intended to write a biography of her father, and transcriptions by Maria Theresa of correspondence between Mundella and Robert Leader, John Daniel Leader and another Sheffield Liberal M.P., Henry Joseph Wilson. The collection does not include any of the business archives of Hine and Mundella. Anthony John Mundella (1825-1897) was born in Leicester of an Italian father and an English mother. After education at a National School he entered the hosiery trade, ultimately becoming a partner in the firm of Hine and Mundella of Nottingham. He became active in the political life of Nottingham, and after giving a series of public lectures in Sheffield was invited to contest the seat in the General Election of 1868. Mundella was Liberal M.P. for Sheffield from 1868 to 1885, and for the Brightside division of the Borough from November 1885 to his death in 1897. -

The Electric Telegraph

To Mark, Karen and Paul CONTENTS page ORIGINS AND DEVELOPMENTS TO 1837 13 Early experiments—Francis Ronalds—Cooke and Wheatstone—successful experiment on the London & Birmingham Railway 2 `THE CORDS THAT HUNG TAWELL' 29 Use on the Great Western and Blackwall railways—the Tawell murder—incorporation of the Electric Tele- graph Company—end of the pioneering stage 3 DEVELOPMENT UNDER THE COMPANIES 46 Early difficulties—rivalry between the Electric and the Magnetic—the telegraph in London—the overhouse system—private telegraphs and the press 4 AN ANALYSIS OF THE TELEGRAPH INDUSTRY TO 1868 73 The inland network—sources of capital—the railway interest—analysis of shareholdings—instruments- working expenses—employment of women—risks of submarine telegraphy—investment rating 5 ACHIEVEMENT IN SUBMARINE TELEGRAPHY I o The first cross-Channel links—the Atlantic cable— links with India—submarine cable maintenance com- panies 6 THE CASE FOR PUBLIC ENTERPRISE 119 Background to the nationalisation debate—public attitudes—the Edinburgh Chamber of Commerce— Frank Ives. Scudamore reports—comparison with continental telegraph systems 7 NATIONALISATION 1868 138 Background to the Telegraph Bill 1868—tactics of the 7 8 CONTENTS Page companies—attitudes of the press—the political situa- tion—the Select Committee of 1868—agreement with the companies 8 THE TELEGRAPH ACTS 154 Terms granted to the telegraph and railway companies under the 1868 Act—implications of the 1869 telegraph monopoly 9 THE POST OFFICE TELEGRAPH 176 The period 87o-1914—reorganisation of the -

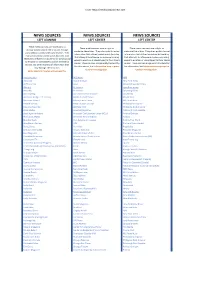

Left Media Bias List

From -https://mediabiasfactcheck.com NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES NEWS SOURCES LEFT LEANING LEFT CENTER LEFT CENTER These media sources are moderately to These media sources have a slight to These media sources have a slight to strongly biased toward liberal causes through moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual moderate liberal bias. They often publish factual story selection and/or political affiliation. They information that utilizes loaded words (wording information that utilizes loaded words (wording may utilize strong loaded words (wording that that attempts to influence an audience by using that attempts to influence an audience by using attempts to influence an audience by using appeal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal appeal to emotion or stereotypes) to favor liberal to emotion or stereotypes), publish misleading causes. These sources are generally trustworthy causes. These sources are generally trustworthy reports and omit reporting of information that for information, but Information may require for information, but Information may require may damage liberal causes. further investigation. further investigation. Some sources may be untrustworthy. Addicting Info ABC News NPR Advocate Above the Law New York Times All That’s Fab Aeon Oil and Water Don’t Mix Alternet Al Jazeera openDemocracy Amandla Al Monitor Opposing Views AmericaBlog Alan Guttmacher Institute Ozy Media American Bridge 21st Century Alaska Dispatch News PanAm Post American News X Albany Times-Union PBS News Hour Backed by Fact Akron Beacon