Journal of Applied Corporate Finance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act

The Straw that Broke the Camel's Back? Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument Antiquates the Antiquities Act ERIC C. RUSNAK* The public lands of the United States have always provided the arena in which we Americans have struggled to fulfill our dreams. Even today dreams of wealth, adventure, and escape are still being acted out on these far flung lands. These lands and the dreams-fulfilled and unfulfilled-which they foster are a part of our national destiny. They belong to all Americans. 1 I. INTRODUCTION For some Americans, public lands are majestic territories for exploration, recreation, preservation, or study. Others depend on public lands as a source of income and livelihood. And while a number of Americans lack awareness regarding the opportunities to explore their public lands, all Americans attain benefits from these common properties. Public land affect all Americans. Because of the importance of these lands, heated debates inevitably arise regarding their use or nonuse. The United States Constitution grants to Congress the "[p]ower to dispose of and make all needful Rules and Regulations respecting the... Property belonging to the United States." 2 Accordingly, Congress, the body representing the populace, determines the various uses of our public lands. While the Constitution purportedly bestows upon Congress sole discretion to manage public lands, the congressionally-enacted Antiquities Act conveys some of this power to the president, effectively giving rise to a concurrent power with Congress to govern public lands. On September 18, 1996, President William Jefferson Clinton issued Proclamation 69203 under the expansive powers granted to the president by the Antiquities Act4 ("the Act") establishing, in the State of Utah, the Grand * B.A., Wittenberg University, 2000; J.D., The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law, 2003 (expected). -

The Operational Aesthetic in the Performance of Professional Wrestling William P

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling William P. Lipscomb III Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Lipscomb III, William P., "The operational aesthetic in the performance of professional wrestling" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3825. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3825 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE OPERATIONAL AESTHETIC IN THE PERFORMANCE OF PROFESSIONAL WRESTLING A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Communication Studies by William P. Lipscomb III B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1990 B.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1991 M.S., University of Southern Mississippi, 1993 May 2005 ©Copyright 2005 William P. Lipscomb III All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am so thankful for the love and support of my entire family, especially my mom and dad. Both my parents were gifted educators, and without their wisdom, guidance, and encouragement none of this would have been possible. Special thanks to my brother John for all the positive vibes, and to Joy who was there for me during some very dark days. -

Tuesday Morning, May 8

TUESDAY MORNING, MAY 8 FRO 6:00 6:30 7:00 7:30 8:00 8:30 9:00 9:30 10:00 10:30 11:00 11:30 COM 4:30 KATU News This Morning (N) Good Morning America (N) (cc) AM Northwest (cc) The View Ricky Martin; Giada De Live! With Kelly Stephen Colbert; 2/KATU 2 2 (cc) (Cont’d) Laurentiis. (N) (cc) (TV14) Miss USA contestants. (N) (TVPG) KOIN Local 6 at 6am (N) (cc) CBS This Morning (N) (cc) Let’s Make a Deal (N) (cc) (TVPG) The Price Is Right (N) (cc) (TVG) The Young and the Restless (N) (cc) 6/KOIN 6 6 (TV14) NewsChannel 8 at Sunrise at 6:00 Today Martin Sheen and Emilio Estevez. (N) (cc) Anderson (cc) (TVG) 8/KGW 8 8 AM (N) (cc) Sit and Be Fit Wild Kratts (cc) Curious George Cat in the Hat Super Why! (cc) Dinosaur Train Sesame Street Rhyming Block. Sid the Science Clifford the Big Martha Speaks WordWorld (TVY) 10/KOPB 10 10 (cc) (TVG) (TVY) (TVY) Knows a Lot (TVY) (TVY) Three new nursery rhymes. (TVY) Kid (TVY) Red Dog (TVY) (TVY) Good Day Oregon-6 (N) Good Day Oregon (N) MORE Good Day Oregon The 700 Club (cc) (TVPG) Law & Order: Criminal Intent Iden- 12/KPTV 12 12 tity Crisis. (cc) (TV14) Positive Living Public Affairs Paid Paid Paid Paid Through the Bible Paid Paid Paid Paid 22/KPXG 5 5 Creflo Dollar (cc) John Hagee Breakthrough This Is Your Day Believer’s Voice Billy Graham Classic Crusades Doctor to Doctor Behind the It’s Supernatural Life Today With Today: Marilyn & 24/KNMT 20 20 (TVG) Today (cc) (TVG) W/Rod Parsley (cc) (TVG) of Victory (cc) (cc) Scenes (cc) (TVG) James Robison Sarah Eye Opener (N) (cc) My Name Is Earl My Name Is Earl Swift Justice: Swift Justice: Maury (cc) (TV14) The Steve Wilkos Show (N) (cc) 32/KRCW 3 3 (TV14) (TV14) Jackie Glass Jackie Glass (TV14) Andrew Wom- Paid The Jeremy Kyle Show (N) (cc) America Now (N) Paid Cheaters (cc) Divorce Court (N) The People’s Court (cc) (TVPG) America’s Court Judge Alex (N) 49/KPDX 13 13 mack (TVPG) (cc) (TVG) (TVPG) (TVPG) (cc) (TVPG) Paid Paid Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Dog the Bounty Hunter A fugitive and Criminal Minds The team must Criminal Minds Hotch has a hard CSI: Miami Inside Out. -

ENDER's GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third

ENDER'S GAME by Orson Scott Card Chapter 1 -- Third "I've watched through his eyes, I've listened through his ears, and tell you he's the one. Or at least as close as we're going to get." "That's what you said about the brother." "The brother tested out impossible. For other reasons. Nothing to do with his ability." "Same with the sister. And there are doubts about him. He's too malleable. Too willing to submerge himself in someone else's will." "Not if the other person is his enemy." "So what do we do? Surround him with enemies all the time?" "If we have to." "I thought you said you liked this kid." "If the buggers get him, they'll make me look like his favorite uncle." "All right. We're saving the world, after all. Take him." *** The monitor lady smiled very nicely and tousled his hair and said, "Andrew, I suppose by now you're just absolutely sick of having that horrid monitor. Well, I have good news for you. That monitor is going to come out today. We're going to just take it right out, and it won't hurt a bit." Ender nodded. It was a lie, of course, that it wouldn't hurt a bit. But since adults always said it when it was going to hurt, he could count on that statement as an accurate prediction of the future. Sometimes lies were more dependable than the truth. "So if you'll just come over here, Andrew, just sit right up here on the examining table. -

Applied Corporate Finance

VOLUME 27 | NUMBER 2 | SPRING 2015 Journal of APPLIED CORPORATE FINANCE In This Issue: Sustainability and Shareholder Value Meaning and Momentum in the Integrated Reporting Movement 8 Robert G. Eccles, Harvard Business School, Michael P. Krzus, Mike Krzus Consulting, and Sydney Ribot, Independent Researcher Sustainability versus The System: An Operator’s Perspective 18 Ken Pucker, Berkshire Partners and Boston University’s Questrom School of Business Transparent Corporate Objectives— 28 Michael J. Mauboussin, Credit Suisse, and A Win-Win for Investors and the Companies They Invest In Alfred Rappaport, Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University Integrated Reporting and Investor Clientele 34 George Serafeim, Harvard Business School An Alignment Proposal: Boosting the Momentum of Sustainability Reporting 52 Andrew Park and Curtis Ravenel, Bloomberg LP Growing Demand for ESG Information and Standards: 58 Levi S. Stewart, Sustainability Accounting Standards Understanding Corporate Opportunities as Well as Risks Board (SASB) ESG Integration in Corporate Fixed Income 64 Robert Fernandez and Nicholas Elfner, Breckinridge Capital Advisors The “Science” and “Art” of High Quality Investing 73 Dan Hanson and Rohan Dhanuka, Jarislowsky Fraser Global Investment Management Intangibles and Sustainability: 87 Mary Adams, Smarter-Companies Holistic Approaches to Measuring and Managing Value Creation Tracking “Real-time” Corporate Sustainability Signals 95 Greg Bala and Hendrik Bartel, TruValue Labs, and Using Cognitive Computing James P. Hawley and Yung-Jae Lee, Saint Mary’s College of California Models of Best Practice in Integrated Reporting 2015 108 Robert G. Eccles, Harvard Business School, Michael P. Krzus, Mike Krzus Consulting, and Sydney Ribot, Independent Researcher Meaning and Momentum in the Integrated Reporting Movement by Robert G. -

MCHS-2000.Pdf

TABLEof CONTENTS 0/udenl Bife ...... .. 2 Clubs ......... ..... .. 24 0porls ............... 50 :?eopfe . 94 !Jacufly ........ 96 !Jres.hmen .... 110 0ophomores . 122 ;Juniors ........ 132 0eniors ........ 142 7/cfs .. ............... 166 Luis Montigo makes use of his lime while waiting to get up to his locker. Students need to be ingenious organizers to stay on top. Seniors ham it up after deli verin g new desks to Ms. Anthony's room. Janneth Casas, Gilda Onerero. Perla Jaurequi. and Ray Musquiz team up on Macbeth in Ms. K·s British Lit. Ivan Ayon and Erica Hill play a little one on one soccer after school, while Valeriano Chavez referees. 3 l JUISl, IFOOILIING AlflOUINID by Cv~LAIUivf~£¼' Most Marian students feel pretty lucky. After all, we're located in an almost always sunny spot. We could surf and go skiing on the same day if we wanted to. We're a school that's safe. In fact, everyone gets along pretty well. We're on the small side, which has some advantages. For one thing, just about everybody knows everyone. Our teachers may get mad sometimes, but we know they really care about us. And Marian is fun. There's always time to fool around a little: talk with friends, play games and just goof off. That's what we sometimes like to do best. That's what will make memories for us when we look back and remember the time of our lives. Margaret Alcock and Philip Disney look on patiently as James Perkins contemplates his next move. Many students give up their lunch break to play chess in the library. -

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series

Beyond Greed and Fear Financial Management Association Survey and Synthesis Series The Search for Value: Measuring the Company's Cost of Capital Michael C. Ehrhardt Managing Pension Plans: A Comprehensive Guide to Improving Plan Performance Dennis E. Logue and Jack S. Rader Efficient Asset Management: A Practical Guide to Stock Portfolio Optimization and Asset Allocation Richard O. Michaud Real Options: Managing Strategic Investment in an Uncertain World Martha Amram and Nalin Kulatilaka Beyond Greed and Fear: Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin Dividend Policy: Its Impact on Form Value Ronald C. Lease, Kose John, Avner Kalay, Uri Loewenstein, and Oded H. Sarig Value Based Management: The Corporate Response to Shareholder Revolution John D. Martin and J. William Petty Debt Management: A Practitioner's Guide John D. Finnerty and Douglas R. Emery Real Estate Investment Trusts: Structure, Performance, and Investment Opportunities Su Han Chan, John Erickson, and Ko Wang Trading and Exchanges: Market Microstructure for Practitioners Larry Harris Beyond Greed and Fear Understanding Behavioral Finance and the Psychology of Investing Hersh Shefrin 2002 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Copyright © 2002 by Oxford University Press, Inc. -

Cover Next Page > Cover Next Page >

cover next page > title : High Yield Bonds : Market Structure, Portfolio Management, and Credit Risk Modeling [Irwin Library of Investment & Finance] author : Barnhill, Theodore M. publisher : McGraw-Hill Professional isbn10 | asin : print isbn13 : 9780070067868 ebook isbn13 : 9780071376969 language : English subject Junk bonds, Portfolio management, Credit. publication date : 1999 lcc : HG4963.H528 1999eb ddc : 332.63/23 subject : Junk bonds, Portfolio management, Credit. cover next page > < previous page page_i next page > Page i High Yield Bonds Market Structure, Portfolio Management, and Credit Risk Modeling Edited by Theodore M. Barnhill, Jr. William F. Maxwell, and Mark R. Shenkman < previous page page_i next page > < previous page page_ii next page > Page ii Copyright © 1999 by The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. 007-137696-8 The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-006786-4. All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps. McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. -

Maximum Withdrawal Rates

VOLUME 29 | NUMBER 4 | FALL 2017 Journal of APPLIED CORPORATE FINANCE In This Issue: Financial Regulation Has Financial Regulation Been a Flop? (or How to Reform Dodd-Frank) 8 Charles W. Calomiris, Columbia University Statement of the Financial Economists Roundtable 25 Charles W. Calomiris, Columbia University; Larry Harris, Uni- Bank Capital as a Substitute for Prudential Regulation versity of Southern California; Catherine Schrand, University of Pennsylvania; Roman L. Weil, University of Chicago High Frequency Trading and the New Stock Market: 30 Merritt B. Fox, Columbia Law School, Lawrence R. Glosten, Sense and Nonsense Columbia Business School, and Gabriel V. Rauterberg, Michigan Law School Shadow Banking, Risk Transfer, and Financial Stability 45 Christopher L. Culp, Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, and Andrea M. P. Neves, Seven Consulting Why European Banks Are Undercapitalized and What Should Be Done About It 65 John D. Finnerty, Fordham University, and Laura Gonzalez, California State University, Long Beach Bloomberg Intelligence Roundtable on 72 Participants: Clifford Smith, Gregory Milano, Joel Levington, The Theory and Practice of Capital Structure Management Asthika Goonewardene, Gina Martin Adams, Michael Holland, and Jonathan Palmer. Moderated by Don Chew. Leverage and Taxes: Evidence from the Real Estate Industry 86 Michael J. Barclay, University of Rochester, Shane M. Heitzman, University of Southern California, Clifford W. Smith, University of Rochester Formulaic Transparency: The Hidden Enabler of Exceptional U.S. Securitization 96 Amar Bhidé, Tufts University How Investment Opportunities Affect Optimal Capital Structure 112 Stanley Myint, BNP Paribas and University of Oxford, Antonio Lupi, BNP Paribas, and Dimitrios P. Tsomocos, University of Oxford How to Integrate ESG into Investment Decision-Making: 125 Robert G. -

59Th Annual Distinguished Service Award Harvey P. Eisen, BS BA

59th Annual Distinguished Service Award Harvey P. Eisen, BS BA '64 Chairman, CEO and Director, Wright Investors' Service Holdings, Inc. Chairman and Managing Partner; Bedford Oak Advisers, LLC Chairman and Director, GP Strategies Harvey P. Eisen is Chairman, CEO and Director of Wright Investors’ Service Holdings, Inc. (WISH), formerly National Patent Development Corporation. He has also served as Chairman of Bedford Oak Advisors, LLC, an investment partnership since 1998, and Chairman and Director of GP Strategies since 2004. He was previously Senior Vice President of Travelers, Inc. and held various executive positions with Primerica, SunAmerica Corp., and Integrated Resources Asset Management. Mr. Eisen was president and portfolio manager of Eisen Capital Management for 10 years. He began his career as an analyst with Stifel, Nicolaus & Co. and Wertheim. Mr. Eisen has served on the Strategic Development Board for the Trulaske College of Business, University of Missouri since 1995 where he established the first accredited course on the Warren Buffett Principles of Investing. He also serves on the Zanvyl Krieger School of Arts and Sciences Advisory Board for Johns Hopkins University and is a member of the Carey Business School Board of Overseers and the Hopkins Parents Council. Mr. Eisen is widely recognized as one of the country’s leading portfolio managers. With over three decades of investment experience, he is often consulted by the national media for his expert views on all phases of the investment marketplace and is frequently quoted in The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, Pension World, U.S. News & World Report, Financial World and Business Week, among others. -

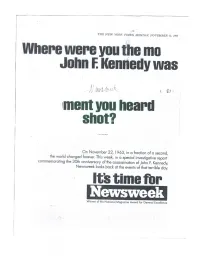

Its Time For

THE NEW YORK TIMES, MONDAY, NOVEMBER 15, 1993 Where were you the mo John F. Kennedy was tur1/1!:-i z Iment you heard shot? b011,3,111. On November 22, 1963, in a fraction of a second, the world changed forever. This week, in a special investigative report commemorating the 30th anniversary of the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Newsweek looks back at the events of that terrible day. Its time for Newsweek. Winner of the National Magazine Award for General Excellence Newsweek Ir HO' 71:171 "_, .‘" It's Nut Whet YOu Think was in my third year of college, and I was walking with my friend, Alan Placa, now Monsignor Placa. Someone came up to us and said that President Kennedy had been shot. At first, we thought it was a joke or a wild report. Then, some- one else said it to us. We went to a radio nearby where we heard the news report. Then we went to I remember the day well. I was at my car and put on the radio We the office when I heard. I ran out sat in the car for over one hour just of my office into the hall - I wanted listening in shock because we io call out the news to everyone. I didn't wont to leave until they started to cry; I couldn't get the announced it, that he was actually words out, Everyone stayed con- dead " gregated in the halls for some Rudolph Giuliani time. We all wanted to be together Mayor Elect, City of New York with each other in our sorrow.' Ed Meyer Chairman/President and Chief Executive Officer Grey Advertising was leaving the Beverly Hills Post Office. -

Applied Corporate Finance

VOLUME 31 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 2019 Journal of APPLIED CORPORATE FINANCE IN THIS ISSUE: Columbia Law School Symposium on Corporate Governance “Counter-Narratives”: On Corporate Purpose and Shareholder Value(s) Corporate 10 Session I: Corporate Purpose and Governance Colin Mayer, Oxford University; Ronald Gilson, Columbia and Stanford Law Schools; and Martin Purpose— Lipton, Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz LLP. 26 Session II: Capitalism and Social Insurance and EVA Jeffrey Gordon, Columbia Law School. Moderated by Merritt Fox, Columbia Law School. 32 Session III: Securities Law in Twenty-First Century America: Once More? A Conversation with SEC Commissioner Rob Jackson Robert Jackson, Commissioner, U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Moderated by John Coffee, Columbia Law School. 44 Session IV: The Law, Corporate Governance, and Economic Justice Chief Justice Leo Strine, Delaware Supreme Court; Mark Roe, Harvard Law School; Jill Fisch, University of Pennsylvania Law School; and Bruce Kogut, Columbia Business School. Moderated by Eric Talley, Columbia Law School. 64 Session V: Macro Perspectives: Bigger Problems than Corporate Governance Bruce Greenwald and Edmund Phelps, Columbia Business School. Moderated by Joshua Mitts, Columbia Law School. 74 Is Managerial Myopia a Persistent Governance Problem? David J. Denis, University of Pittsburgh 81 The Case for Maximizing Long-Run Shareholder Value Diane Denis, University of Pittsburgh 90 A Tribute to Joel Stern Bennett Stewart, Institutional Shareholder Services 95 A Look Back at the Beginning of EVA and Value-Based Management: An Interview with Joel M. Stern Interviewed by Joseph T. Willett 103 EVA, Not EBITDA: A New Financial Paradigm for Private Equity Firms Bennett Stewart, Institutional Shareholder Services 116 Beyond EVA Gregory V.