Electronic Fuel Injection Techniques for Hydrogen Powered I.C. Engines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water/Methanol Injection: Frequently Asked Questions

Water/Methanol Injection: Frequently Asked Questions Water/methanol injection is nothing new. It has been used as far back as World War II to help power German fighter planes. Yet it never seemed to catch on as a mainstream power adder in the hot rodding world—until recent years. Many companies are now offering easy to install water/methanol injections systems for affordable prices. Available for naturally aspirated or forced induction gasoline and diesel applications, these systems inject a roughly 50/50 mixture of methanol and water into the engine using a high-pressure pump. This magical mixture allows for more ignition timing, increases boost capability in supercharged or turbocharged applications, lowers air intake temperature, and provides an additional source of very high-octane fuel—all without increasing the chance of damaging detonation. Water injection systems are predominantly useful in forced induction (turbocharged or supercharged), internal combustion engines. Only in extreme cases such as very high compression ratios, very low octane fuel or too much ignition advance can it benefit a normally aspirated engine. The system has been around for a long time since it was already used in some World War II aircraft engines, which allowed them to produce more power and therefore fly at higher altitudes. A water injection system works similarly to a fuel injection system only it injects water instead of fuel. Water injection is not to be confused with water spraying on the intercooler's surface, water spraying is much less efficient and far less sophisticated. A turbocharger or supercharger essentially compresses the air going into the engine in order to force more air than would be possible with the atmospheric pressure. -

Experimental Investigation of HCCI Engine with Ethanol Manifold Injection

Journal of Basic and Applied Engineering Research Print ISSN: 2350-0077; Online ISSN: 2350-0255; Volume 1, Number 4; October, 2014 pp. 16-20 © Krishi Sanskriti Publications http://www.krishisanskriti.org/jbaer.html Experimental Investigation of HCCI Engine with Ethanol Manifold Injection Aswin R.1, Karthick Sundar R.2, Aravindraj S.3, Bhaskar K.4 1,2 Department of Automobile Engineering Rajalakshmi Engineering College, Thandalam, Chennai, India Abstract: In this work the homogeneous charge compression occurs at the boundary of fuel-air mixing, caused by an ignition engine with manifold ethanol injection and diesel in the injection event, to initiate combustion. in-cylinder injection were selected as fuels and test conducted in a single cylinder constant speed diesel engine.HCCI combustion The defining characteristics of HCCI engine is that the incorporates the advantages of both spark ignition engines and compression ignition engines. The effect of pre mixed ratio and ignition occurs at several places at a time which makes the injection timing were studied to determine the performance, fuel/air mixture burn nearly spontaneously. There is no direct emission and combustion characteristics of HCCI engine.In initiator of combustion. This makes the process inherently cylinder pressure crank angle diagram was obtained using AVL challenging to control. However, with advances in piezo electric pressure transducer and AVL crank angle decoder. microprocessors and a physical understanding of the ignition The combustion parameters like peak pressure, combustion process, HCCI can be controlled to achieve gasoline engine- duration, heat release rate, cumulative heat release rate, mass like emissions along with diesel engine like efficiency. -

05 NG Engine Technology.Pdf

Table of Contents NG Engine Technology Subject Page New Generation Engine Technology . .5 Turbocharging . .6 Turbocharging Terminology . .6 Basic Principles of Turbocharging . .7 Bi-turbocharging . .10 Air Ducting Overview . .12 Boost-pressure Control (Wastegate) . .14 Blow-off Control (Diverter Valves) . .15 Charge-air Cooling . .18 Direct Charge-air Cooling . .18 Indirect Charge Air Cooling . .18 Twin Scroll Turbocharger . .20 Function of the Twin Scroll Turbocharger . .22 Diverter valve . .22 Tuned Pulsed Exhaust Manifold . .23 Load Control . .24 Controlled Variables . .25 Service Information . .26 Limp-home Mode . .26 Direct Injection . .28 Direct Injection Principles . .29 Mixture Formation . .30 High Precision Injection . .32 HPI Function . .33 High Pressure Pump Function and Design . .35 Pressure Generation in High-pressure Pump . .36 Limp-home Mode . .37 Fuel System Safety . .38 Piezo Fuel Injectors . .39 Injector Design and Function . .40 Injection Strategy . .42 Initial Print Date: 09/06 Revision Date: 03/11 Subject Page Piezo Element . .43 Injector Adjustment . .43 Injector Control and Adaptation . .44 Injector Adaptation . .44 Optimization . .45 HDE Fuel Injection . .46 VALVETRONIC III . .47 Phasing . .47 Masking . .47 Combustion Chamber Geometry . .48 VALVETRONIC Servomotor . .50 Function . .50 Subject Page BLANK PAGE NG Engine Technology Model: All from 2007 Production: All After completion of this module you will be able to: • Understand the technology used on BMW turbo engines • Understand basic turbocharging principles • Describe the benefits of twin Scroll Turbochargers • Understand the basics of second generation of direct injection (HPI) • Describe the benefits of HDE solenoid type direct injection • Understand the main differences between VALVETRONIC II and VALVETRONIC II I 4 NG Engine Technology New Generation Engine Technology In 2005, the first of the new generation 6-cylinder engines was introduced as the N52. -

Water Injection on Commercial Aircraft to Reduce Airport Nitrogen Oxides

NASA/TM—2010-213179 Water Injection on Commercial Aircraft to Reduce Airport Nitrogen Oxides David L. Daggett and Lars Fucke Boeing Commercial Airplane, Seattle, Washington Robert C. Hendricks Glenn Research Center, Cleveland, Ohio David J.H. Eames Rolls-Royce Corporation, Indianapolis, Indiana March 2010 NASA STI Program . in Profile Since its founding, NASA has been dedicated to the • CONFERENCE PUBLICATION. Collected advancement of aeronautics and space science. The papers from scientific and technical NASA Scientific and Technical Information (STI) conferences, symposia, seminars, or other program plays a key part in helping NASA maintain meetings sponsored or cosponsored by NASA. this important role. • SPECIAL PUBLICATION. Scientific, The NASA STI Program operates under the auspices technical, or historical information from of the Agency Chief Information Officer. It collects, NASA programs, projects, and missions, often organizes, provides for archiving, and disseminates concerned with subjects having substantial NASA’s STI. The NASA STI program provides access public interest. to the NASA Aeronautics and Space Database and its public interface, the NASA Technical Reports • TECHNICAL TRANSLATION. English- Server, thus providing one of the largest collections language translations of foreign scientific and of aeronautical and space science STI in the world. technical material pertinent to NASA’s mission. Results are published in both non-NASA channels and by NASA in the NASA STI Report Series, which Specialized services also include creating custom includes the following report types: thesauri, building customized databases, organizing and publishing research results. TECHNICAL PUBLICATION. Reports of completed research or a major significant phase For more information about the NASA STI of research that present the results of NASA program, see the following: programs and include extensive data or theoretical analysis. -

Reduction of NO Emissions in a Turbojet Combustor by Direct Water

Reduction of NO emissions in a turbojet combustor by direct water/steam injection: numerical and experimental assessment Ernesto Benini, Sergio Pandolfo, Serena Zoppellari To cite this version: Ernesto Benini, Sergio Pandolfo, Serena Zoppellari. Reduction of NO emissions in a turbojet combus- tor by direct water/steam injection: numerical and experimental assessment. Applied Thermal Engi- neering, Elsevier, 2009, 29 (17-18), pp.3506. 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2009.06.004. hal-00573476 HAL Id: hal-00573476 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00573476 Submitted on 4 Mar 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Reduction of NO emissions in a turbojet combustor by direct water/steam in- jection: numerical and experimental assessment Ernesto Benini, Sergio Pandolfo, Serena Zoppellari PII: S1359-4311(09)00181-1 DOI: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2009.06.004 Reference: ATE 2830 To appear in: Applied Thermal Engineering Received Date: 10 November 2008 Accepted Date: 2 June 2009 Please cite this article as: E. Benini, S. Pandolfo, S. Zoppellari, Reduction of NO emissions in a turbojet combustor by direct water/steam injection: numerical and experimental assessment, Applied Thermal Engineering (2009), doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2009.06.004 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Terms and Definitions of Fuel Injection Management Systems

THROTTLE BODY TERMS AND DEFINITIONS OF INJECTION (TBI) — In TBI FUEL INJECTION systems the throttle body assembly has two major MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS functions: regulate the air- flow, and house the fuel Throttle Body Assembly (TBA) — The throttle body injectors and the fuel pres- assembly (also called air valve), controls the airflow to the sure regulator. The choices engine through one, two or four butterfly valves and of throttle bodies range provides valve position feedback via the throttle position from single barrel/single sensor. Rotating the throttle lever to open or close the injector unit generally sized for less than 150 HP to four bar- passage into the intake manifold controls the airflow to the rel/four injector unit capable of supporting fuel and air flow for engine. The accelerator pedal controls the throttle lever posi- 600 HP. The injectors are located in an injector pod above the tion. Other functions of the throttle body are idle bypass air throttle valves. The quantity of fuel the injector spray into the control via the idle air control valve, coolant heat for avoiding intake manifold is continuously controlled by the ECU. Most of icing conditions, vacuum signals for the the TBI systems use bottom fed fuel injectors. ancillaries and the sensors. MULTI-POINT FUEL INJECTION (MPFI) — In the multi point fuel FUEL INJECTOR — There are basically three approaches in injection system an injector is located in the intake manifold delivering the fuel to the engine: passage. The fuel is supplied to the injectors via a fuel rail in • Above the throttle plate as in throttle body injection the case of top fed fuel injectors and via a fuel galley in the • In the intake port toward the intake valves as in multi-port injec- intake manifold in the case of bottom fed fuel injectors. -

A Review of Performance-Enhancing Innovative Modifications in Biodiesel Engines

energies Review A Review of Performance-Enhancing Innovative Modifications in Biodiesel Engines T. M. Yunus Khan 1,2 1 Research Center for Advanced Materials Science (RCAMS), King Khalid University, PO Box 9004, Abha 61413, Saudi Arabia; [email protected] 2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, College of Engineering, King Khalid University, Abha 61421, Saudi Arabia Received: 1 August 2020; Accepted: 24 August 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: The ever-increasing demand for transport is sustained by internal combustion (IC) engines. The demand for transport energy is large and continuously increasing across the globe. Though there are few alternative options emerging that may eliminate the IC engine, they are in a developing stage, meaning the burden of transportation has to be borne by IC engines until at least the near future. Hence, IC engines continue to be the prime mechanism to sustain transportation in general. However, the scarcity of fossil fuels and its rising prices have forced nations to look for alternate fuels. Biodiesel has been emerged as the replacement of diesel as fuel for diesel engines. The use of biodiesel in the existing diesel engine is not that efficient when it is compared with diesel run engine. Therefore, the biodiesel engine must be suitably improved in its design and developments pertaining to the intake manifold, fuel injection system, combustion chamber and exhaust manifold to get the maximum power output, improved brake thermal efficiency with reduced fuel consumption and exhaust emissions that are compatible with international standards. This paper reviews the efforts put by different researchers in modifying the engine components and systems to develop a diesel engine run on biodiesel for better performance, progressive combustion and improved emissions. -

Direct Injection of Water Mist in an Intake Manifold Spark Ignition Engine

International Journal of Automotive and Mechanical Engineering (IJAME) ISSN: 2229-8649 (Print); ISSN: 2180-1606 (Online); Volume 12, pp. 2809-2819, July-December 2015 ©Universiti Malaysia Pahang DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15282/ijame.12.2015.1.0236 Direct injection of water mist in an intake manifold spark ignition engine A.R. Babu1*, G. Amba Prasad Rao1 and T. Hari Prasad2 1Department of Mechanical Engineering, NIT, Warangal, 506004, India *Email: [email protected] Phone: +919581993346; Fax: +918572245126 2Department of Mechanical Engineering, SVEC, Tirupati, 5171024, India ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is to investigate the effects of water mist (WM) injected directly into an intake manifold spark ignition (SI) engine. WM flows through a nozzle at the throttle body of the four-cylinder four-stroke multi-point injection engine for testing the performance of exhaust emission system. The water is pumped in mist form into the intake manifold with an air-fuel mixture through the nozzle, which is located on the throttle body. Experimental work and simulation methods are combined by the presence and absence of WM addition, and the performance as well as emission produced by the engine is analyzed. The Gamma Technologies (GT) methods are used to simulate the model with and without WM addition. The experimental results indicate that the standard engine performance can be used to validate the simulation model. The engine measures include various parameters such as brake power, torque, volumetric efficiency, spark advance timing, and the concentration of CO and NOx with water and without water addition to the SI engine (i.e., the power, torque, volumetric efficiency of the engine is increased up to 10%). -

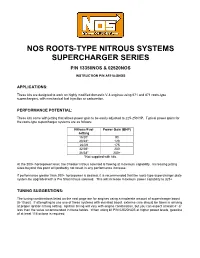

Nos Roots-Type Nitrous Systems Supercharger Series

NOS ROOTS-TYPE NITROUS SYSTEMS SUPERCHARGER SERIES P/N 13350NOS & 02520NOS INSTRUCTION P/N A5118-SNOS APPLICATIONS: These kits are designed to work on highly modified domestic V-8 engines using 671 and 871 roots-type superchargers, with mechanical fuel injection or carburetion. PERFORMANCE POTENTIAL: These kits come with jetting that allows power gain to be easily adjusted to 225-250 HP. Typical power gains for the roots-type supercharger systems are as follows: Nitrous/Fuel Power Gain (BHP) Jetting 16/20* 80 20/24* 120 26/29 175 32/36* 200 36/38* 200+ *Not supplied with kits. At the 200+ horsepower level, the Cheater nitrous solenoid is flowing at maximum capability. Increasing jetting sizes beyond this point will probably not result in any performance increase. If performance greater than 200+ horsepower is desired, it is recommended that the roots-type supercharger plate system be upgraded with a Pro Shot nitrous solenoid. This will increase maximum power capability to 325+. TUNING SUGGESTIONS: The tuning combinations listed on the next page are for engines using a moderate amount of supercharger boost (5-10 psi). If attempting to use one of these systems with elevated boost, extreme care should be taken in arriving at proper ignition timing setting. Ignition timing will vary with engine combination, but you can expect at least 4°-8° less than the value recommended in these tables. When using kit P/N 02520NOS at higher power levels, gasoline of at least 116 octane is required. Suggested Tuning Combinations for NOS Roots-Type Super -

FUEL INJECTION SYSTEM for CI ENGINES the Function of a Fuel

FUEL INJECTION SYSTEM FOR CI ENGINES The function of a fuel injection system is to meter the appropriate quantity of fuel for the given engine speed and load to each cylinder, each cycle, and inject that fuel at the appropriate time in the cycle at the desired rate with the spray configuration required for the particular combustion chamber employed. It is important that injection begin and end cleanly, and avoid any secondary injections. To accomplish this function, fuel is usually drawn from the fuel tank by a supply pump, and forced through a filter to the injection pump. The injection pump sends fuel under pressure to the nozzle pipes which carry fuel to the injector nozzles located in each cylinder head. Excess fuel goes back to the fuel tank. CI engines are operated unthrottled, with engine speed and power controlled by the amount of fuel injected during each cycle. This allows for high volumetric efficiency at all speeds, with the intake system designed for very little flow restriction of the incoming air. FUNCTIONAL REQUIREMENTS OF AN INJECTION SYSTEM For a proper running and good performance of the engine, the following requirements must be met by the injection system: • Accurate metering of the fuel injected per cycle. Metering errors may cause drastic variation from the desired output. The quantity of the fuel metered should vary to meet changing speed and load requirements of the engine. • Correct timing of the injection of the fuel in the cycle so that maximum power is obtained. • Proper control of rate of injection so that the desired heat-release pattern is achieved during combustion. -

AP-42, Vol. I, 3.3: Gasoline and Diesel Industrial Engines

3.3 Gasoline And Diesel Industrial Engines 3.3.1 General The engine category addressed by this section covers a wide variety of industrial applications of both gasoline and diesel internal combustion (IC) engines such as aerial lifts, fork lifts, mobile refrigeration units, generators, pumps, industrial sweepers/scrubbers, material handling equipment (such as conveyors), and portable well-drilling equipment. The three primary fuels for reciprocating IC engines are gasoline, diesel fuel oil (No.2), and natural gas. Gasoline is used primarily for mobile and portable engines. Diesel fuel oil is the most versatile fuel and is used in IC engines of all sizes. The rated power of these engines covers a rather substantial range, up to 250 horsepower (hp) for gasoline engines and up to 600 hp for diesel engines. (Diesel engines greater than 600 hp are covered in Section 3.4, "Large Stationary Diesel And All Stationary Dual-fuel Engines".) Understandably, substantial differences in engine duty cycles exist. It was necessary, therefore, to make reasonable assumptions concerning usage in order to formulate some of the emission factors. 3.3.2 Process Description All reciprocating IC engines operate by the same basic process. A combustible mixture is first compressed in a small volume between the head of a piston and its surrounding cylinder. The mixture is then ignited, and the resulting high-pressure products of combustion push the piston through the cylinder. This movement is converted from linear to rotary motion by a crankshaft. The piston returns, pushing out exhaust gases, and the cycle is repeated. There are 2 methods used for stationary reciprocating IC engines: compression ignition (CI) and spark ignition (SI). -

Fuel Injection and Anti-Detonation

Fuel Injection • These systems are similar to the Bendix/Stromberg pressure carburetors. • Air / fuel metering is accomplished by one device, fuel distribution occurs by intake distribution pipes. Unliscensed copyrighted material - W. North 1998 Fuel Injection • Manufacturers – Bendix – Contentintal Unliscensed copyrighted material - W. North 1998 Fuel Injection • Bendix • RS and RSA systems • Has four main sections – Air metering and regulation – fuel regulation – fuel metering – fuelUnliscensed distribution copyrighted material - W. North 1998 Fuel Injection • Uses the same A, B, C, D, pressures A = Impact air pressure B = Venturi air pressure C = Metered fuel pressure D = Fuel inlet pressure and Flow divider discharge pressure Unliscensed copyrighted material - W. North 1998 Fuel Injection • Air metering and regulation – accomplished by throttle plate and a throttle body assembly. – impact air and venturi air pressures are sourced here. – automatic mixture control valve regulates pressure value of impact air with venturi air. Unliscensed copyrighted material - W. North 1998 Fuel Injection • Fuel regulation – diaphragms and poppet valve attached to throttle assembly. – fuel inlet pressure closes poppet valve – metered fuel pressure and A - B pressure differential open poppet. Unliscensed copyrighted material - W. North 1998 Fuel Injection – balancing springs alter diaphragm values for low airflow idle conditions. – springs assist poppet valve to open for idle fuel delivery. – idle rotary valve is linked to throttle valve. Unliscensed copyrighted material - W. North 1998 Fuel Injection • Fuel metering section includes: – 74 micron finger screen – idle/enrichment fuel control rotary valve. – main and enrichment metering jets. – manual mixture and idle cut off rotary valve. Unliscensed copyrighted material - W. North 1998 Fuel Injection • Fuel distribution – metered fuel passes the poppet valve into plumbing to the flow divider where it forces open the pressurizing valve.