A Review of Hydrogen Direct Injection for Internal Combustion Engines: Towards Carbon-Free Combustion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Piedmont Service: Hydrogen Fuel Cell Locomotive Feasibility

The Piedmont Service: Hydrogen Fuel Cell Locomotive Feasibility Andreas Hoffrichter, PhD Nick Little Shanelle Foster, PhD Raphael Isaac, PhD Orwell Madovi Darren Tascillo Center for Railway Research and Education Michigan State University Henry Center for Executive Development 3535 Forest Road, Lansing, MI 48910 NCDOT Project 2019-43 FHWA/NC/2019-43 October 2020 -i- FEASIBILITY REPORT The Piedmont Service: Hydrogen Fuel Cell Locomotive Feasibility October 2020 Prepared by Center for Railway Research and Education Eli Broad College of Business Michigan State University 3535 Forest Road Lansing, MI 48910 USA Prepared for North Carolina Department of Transportation – Rail Division 860 Capital Boulevard Raleigh, NC 27603 -ii- Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA/NC/2019-43 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date The Piedmont Service: Hydrogen Fuel Cell Locomotive Feasibility October 2020 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Andreas Hoffrichter, PhD, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2384-4463 Nick Little Shanelle N. Foster, PhD, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9630-5500 Raphael Isaac, PhD Orwell Madovi Darren M. Tascillo 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) Center for Railway Research and Education 11. Contract or Grant No. Michigan State University Henry Center for Executive Development 3535 Forest Road Lansing, MI 48910 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Final Report Research and Development Unit 104 Fayetteville Street December 2018 – October 2020 Raleigh, North Carolina 27601 14. Sponsoring Agency Code RP2019-43 Supplementary Notes: 16. -

Diesel and Fuel-Oil Engines

HdiiUiiat uuioTAt* VI i nPicrence moK not to do AUG 2 ^ : , CuKCH JlUili lilO L, iDi slil CS102E-42 Jf' Engines, Diese! and fuei-oil (export classifications) U. S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE JESSE H. JONES, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS LYMAN J. BRIGGS, Director DIESEL AND FUEL-OIL ENGINES (Export Classifications) COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS102E-42 Effective Date for New Production from October 30, 1942 A RECORDED VOLUNTARY STANDARD OF THE TRADE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1942 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 10 cents . U. S. Department of Commerce National Bureau of Standard? PROMULGATION of COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS102E-42 for DIESEL AND FUEL-OIL ENGINES (Export Classifications) On January 30, 1942, at the instance of the Diesel Engine Manu- facturers’ Association, a conference of representative manufacturers adopted a recommended commercial standard for Diesel and fuel -oil engines (export classifications). Those concerned have since accepted and approved the standard as shown herein for promulgation by the U. S. Department of Commerce, through the National Bureau of Standards. The standard is effective for new production from October 30, 1942. Promulgation recommended I. J. Fairchild, Chieff Division of Trade Standards, Promulgated. Lyman J. Briggs, Director^ National Bureau of Standards, Promulgation approved. Jesse H. Jones, Secretary of Commerce. II DIESEL AND FUEL-OIL ENGINES (Export Classifications) COMMERCIAL STANDARD CS102E-42 PARTS Page 1. Nomenclature and definitions.. ' 1 2. Slow- and medium-speed stationary Diesel engines 7 3. Slow- and medium-speed marine Diesel engines 13 4. Small, medium- and high-speed stationary, marine, and portable Diesel engines 19 5. -

A Review of Energy Storage Technologies' Application

sustainability Review A Review of Energy Storage Technologies’ Application Potentials in Renewable Energy Sources Grid Integration Henok Ayele Behabtu 1,2,* , Maarten Messagie 1, Thierry Coosemans 1, Maitane Berecibar 1, Kinde Anlay Fante 2 , Abraham Alem Kebede 1,2 and Joeri Van Mierlo 1 1 Mobility, Logistics, and Automotive Technology Research Centre, Vrije Universiteit Brussels, Pleinlaan 2, 1050 Brussels, Belgium; [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (T.C.); [email protected] (M.B.); [email protected] (A.A.K.); [email protected] (J.V.M.) 2 Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Jimma Institute of Technology, Jimma University, Jimma P.O. Box 378, Ethiopia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +32-485659951 or +251-926434658 Received: 12 November 2020; Accepted: 11 December 2020; Published: 15 December 2020 Abstract: Renewable energy sources (RESs) such as wind and solar are frequently hit by fluctuations due to, for example, insufficient wind or sunshine. Energy storage technologies (ESTs) mitigate the problem by storing excess energy generated and then making it accessible on demand. While there are various EST studies, the literature remains isolated and dated. The comparison of the characteristics of ESTs and their potential applications is also short. This paper fills this gap. Using selected criteria, it identifies key ESTs and provides an updated review of the literature on ESTs and their application potential to the renewable energy sector. The critical review shows a high potential application for Li-ion batteries and most fit to mitigate the fluctuation of RESs in utility grid integration sector. -

! National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics

! . \ i NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR AERONAUTICS TECHNICAL NOTE No. 1374 EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES OF THE KNOCK - LIlvITTED BLENDIDG CHARACTERISTICS OF AVIATION FUELS II - INVESTIGATION OF LEADED PARAFFINIC FUELS IN AN AIR-COOLED CYLrnDER By Jerrold D. Wear and Newell D. Sanders Flight Propulsion Research Laboratory Cleveland, Ohio Washington July 1947 , \ I NATIONAL ADVISORY COMMITTEE FOR AERONAUTICS TN 1374 EXPERIMENTAL STUDIES OF THE KNOCK-LIMITED BLENDING CH.~~ACTERISTICS OF AVIATION FUELS II - INVESTIGATION OF LEADED PARAFFINIC FUELS IN ~~ AIR-COOLED CYLINDER By Jerrold D. Wear and. Newell D. Sanders SUMMARY The relation between knock limit and blend composition of selected aviation fuel components individually blended with virgin base and ''lith alkylate was determined in a full-scale air-cooled aircraft-·engine cylinder. In addition the follow ing correlations were examined: (a) The knock-·limited performance of a full -scale engine at lean-mixture operation plotted against the knock-limited perform ance of the engine at rich-mixture operation for a series of fuels (b) The knock-limited performance of a full-scale engine at rich-mixture operation plotted against the knock-limited perform ance at rich-mixture operation of a small-scale engine for a series of fuels In each case the following methods of specifying the knock limi ted perfOl'IDanCe of the engine were investigated: (l) Knock·-limited indicated mean effective pressure (2) percentage of S-4 plus 4 ml T~~ per gallon in M-4 plus 4 ml TEL per gallon to give an equal knock-limited indicated mean effective pressure (3) Ratio of indicated mean effective pressure of test fuel ~o indicated mean effective pressure of clear S-4 reference fuel, all other conditions being the same . -

Experimental and Modeling Study of the Flammability of Fuel Tank DE-AC36-08-GO28308 Headspace Vapors from High Ethanol Content Fuels 5B

An Experimental and Modeling Subcontract Report NREL/SR-540-44040 Study of the Flammability of October 2008 Fuel Tank Headspace Vapors from High Ethanol Content Fuels D. Gardiner, M. Bardon, and G. Pucher Nexum Research Corporation Mallorytown, K0E 1R0, Canada An Experimental and Modeling Subcontract Report NREL/SR-540-44040 Study of the Flammability of October 2008 Fuel Tank Headspace Vapors from High Ethanol Content Fuels D. Gardiner, M. Bardon, and G. Pucher Nexum Research Corporation Mallorytown, K0E 1R0, Canada NREL Technical Monitor: M. Melendez Prepared under Subcontract No. XCI-5-55505-01 Period of Performance: August 2005 – December 2008 National Renewable Energy Laboratory 1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, Colorado 80401-3393 303-275-3000 • www.nrel.gov NREL is a national laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC Contract No. DE-AC36-08-GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. Neither the United States government nor any agency thereof, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States government or any agency thereof. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or any agency thereof. -

Comparison of Hydrogen Powertrains with the Battery Powered Electric Vehicle and Investigation of Small-Scale Local Hydrogen Production Using Renewable Energy

Review Comparison of Hydrogen Powertrains with the Battery Powered Electric Vehicle and Investigation of Small-Scale Local Hydrogen Production Using Renewable Energy Michael Handwerker 1,2,*, Jörg Wellnitz 1,2 and Hormoz Marzbani 2 1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, University of Applied Sciences Ingolstadt, Esplanade 10, 85049 Ingolstadt, Germany; [email protected] 2 Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, School of Engineering, Plenty Road, Bundoora, VIC 3083, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Climate change is one of the major problems that people face in this century, with fossil fuel combustion engines being huge contributors. Currently, the battery powered electric vehicle is considered the predecessor, while hydrogen vehicles only have an insignificant market share. To evaluate if this is justified, different hydrogen power train technologies are analyzed and compared to the battery powered electric vehicle. Even though most research focuses on the hydrogen fuel cells, it is shown that, despite the lower efficiency, the often-neglected hydrogen combustion engine could be the right solution for transitioning away from fossil fuels. This is mainly due to the lower costs and possibility of the use of existing manufacturing infrastructure. To achieve a similar level of refueling comfort as with the battery powered electric vehicle, the economic and technological aspects of the local small-scale hydrogen production are being investigated. Due to the low efficiency Citation: Handwerker, M.; Wellnitz, and high prices for the required components, this domestically produced hydrogen cannot compete J.; Marzbani, H. Comparison of with hydrogen produced from fossil fuels on a larger scale. -

Liquefied Natural Gas Deerfoot Consulting Inc. Liquefied Natural Gas Liquefied Methane; LNG. Fuel. Not Available. Fortisbc 16705

Liquefied Natural Gas SAFETY DATA SHEET Date of Preparation: January 7, 2019 Section 1: IDENTIFICATION Product Name: Liquefied Natural Gas Synonyms: Liquefied Methane; LNG. Product Use: Fuel. Restrictions on Use: Not available. Manufacturer/Supplier: FortisBC 16705 Fraser Highway Surrey, BC V3S 2X7 Phone Number: Tilbury: (604) 946-4818 , Mt. Hayes: (236) 933-2060 Emergency Phone: FortisBC Gas Emergency: 1-800-663-9911 LNG Transportation Emergency: 1-877-889-2002 Date of Preparation of SDS: January 7, 2019 Section 2: HAZARD(S) IDENTIFICATION GHS INFORMATION Classification: Flammable Gases, Category 1 Gases Under Pressure - Refrigerated Liquefied Gas Simple Asphyxiant, Category 1 LABEL ELEMENTS Hazard Pictogram(s): Signal Word: Danger Hazard Extremely flammable gas. Statements: Contains refrigerated gas; may cause cryogenic burns or injury. May displace oxygen and cause rapid suffocation. Precautionary Statements Prevention: Keep away from heat, hot surfaces, sparks, open flames and other ignition sources. No smoking. Wear cold insulating gloves and either face shield or eye protection. Response: Get immediate medical advice/attention. Thaw frosted parts with lukewarm water. Do not rub affected area. Leaking gas fire: Do not extinguish, unless leak can be stopped safely. In case of leakage, eliminate all ignition sources. Storage: Store in a well-ventilated place. Disposal: Not applicable. Hazards Not Otherwise Classified: Not applicable. Ingredients with Unknown Toxicity: None. This material is considered hazardous by the OSHA Hazard Communication Standard, (29 CFR 1910.1200). This material is considered hazardous by the Hazardous Products Regulations. Page 1 of 11 Deerfoot Consulting Inc. Liquefied Natural Gas SAFETY DATA SHEET Date of Preparation: January 7, 2019 Section 3: COMPOSITION / INFORMATION ON INGREDIENTS Hazardous Ingredient(s) Common name / CAS No. -

An Experimental Study on Performance and Emission Characteristics of a Hydrogen Fuelled Spark Ignition Engine

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace@IZTECH Institutional Repository International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 32 (2007) 2066–2072 www.elsevier.com/locate/ijhydene An experimental study on performance and emission characteristics of a hydrogen fuelled spark ignition engine Erol Kahramana, S. Cihangir Ozcanlıb, Baris Ozerdemb,∗ aProgram of Energy Engineering, Izmir Institute of Technology, Urla, Izmir 35430, Turkey bDepartment of Mechanical Engineering, Izmir Institute of Technology, Urla, Izmir 35430, Turkey Received 2 August 2006; accepted 2 August 2006 Available online 2 October 2006 Abstract In the present paper, the performance and emission characteristics of a conventional four cylinder spark ignition (SI) engine operated on hydrogen and gasoline are investigated experimentally. The compressed hydrogen at 20 MPa has been introduced to the engine adopted to operate on gaseous hydrogen by external mixing. Two regulators have been used to drop the pressure first to 300 kPa, then to atmospheric pressure. The variations of torque, power, brake thermal efficiency, brake mean effective pressure, exhaust gas temperature, and emissions of NOx, CO, CO2, HC, and O2 versus engine speed are compared for a carbureted SI engine operating on gasoline and hydrogen. Energy analysis also has studied for comparison purpose. The test results have been demonstrated that power loss occurs at low speed hydrogen operation whereas high speed characteristics compete well with gasoline operation. Fast burning characteristics of hydrogen have permitted high speed engine operation. Less heat loss has occurred for hydrogen than gasoline. NOx emission of hydrogen fuelled engine is about 10 times lower than gasoline fuelled engine. -

Terms and Definitions of Fuel Injection Management Systems

THROTTLE BODY TERMS AND DEFINITIONS OF INJECTION (TBI) — In TBI FUEL INJECTION systems the throttle body assembly has two major MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS functions: regulate the air- flow, and house the fuel Throttle Body Assembly (TBA) — The throttle body injectors and the fuel pres- assembly (also called air valve), controls the airflow to the sure regulator. The choices engine through one, two or four butterfly valves and of throttle bodies range provides valve position feedback via the throttle position from single barrel/single sensor. Rotating the throttle lever to open or close the injector unit generally sized for less than 150 HP to four bar- passage into the intake manifold controls the airflow to the rel/four injector unit capable of supporting fuel and air flow for engine. The accelerator pedal controls the throttle lever posi- 600 HP. The injectors are located in an injector pod above the tion. Other functions of the throttle body are idle bypass air throttle valves. The quantity of fuel the injector spray into the control via the idle air control valve, coolant heat for avoiding intake manifold is continuously controlled by the ECU. Most of icing conditions, vacuum signals for the the TBI systems use bottom fed fuel injectors. ancillaries and the sensors. MULTI-POINT FUEL INJECTION (MPFI) — In the multi point fuel FUEL INJECTOR — There are basically three approaches in injection system an injector is located in the intake manifold delivering the fuel to the engine: passage. The fuel is supplied to the injectors via a fuel rail in • Above the throttle plate as in throttle body injection the case of top fed fuel injectors and via a fuel galley in the • In the intake port toward the intake valves as in multi-port injec- intake manifold in the case of bottom fed fuel injectors. -

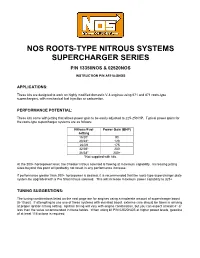

Nos Roots-Type Nitrous Systems Supercharger Series

NOS ROOTS-TYPE NITROUS SYSTEMS SUPERCHARGER SERIES P/N 13350NOS & 02520NOS INSTRUCTION P/N A5118-SNOS APPLICATIONS: These kits are designed to work on highly modified domestic V-8 engines using 671 and 871 roots-type superchargers, with mechanical fuel injection or carburetion. PERFORMANCE POTENTIAL: These kits come with jetting that allows power gain to be easily adjusted to 225-250 HP. Typical power gains for the roots-type supercharger systems are as follows: Nitrous/Fuel Power Gain (BHP) Jetting 16/20* 80 20/24* 120 26/29 175 32/36* 200 36/38* 200+ *Not supplied with kits. At the 200+ horsepower level, the Cheater nitrous solenoid is flowing at maximum capability. Increasing jetting sizes beyond this point will probably not result in any performance increase. If performance greater than 200+ horsepower is desired, it is recommended that the roots-type supercharger plate system be upgraded with a Pro Shot nitrous solenoid. This will increase maximum power capability to 325+. TUNING SUGGESTIONS: The tuning combinations listed on the next page are for engines using a moderate amount of supercharger boost (5-10 psi). If attempting to use one of these systems with elevated boost, extreme care should be taken in arriving at proper ignition timing setting. Ignition timing will vary with engine combination, but you can expect at least 4°-8° less than the value recommended in these tables. When using kit P/N 02520NOS at higher power levels, gasoline of at least 116 octane is required. Suggested Tuning Combinations for NOS Roots-Type Super -

An Evaluation of Turbocharging and Supercharging Options for High-Efficiency Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles

applied sciences Article An Evaluation of Turbocharging and Supercharging Options for High-Efficiency Fuel Cell Electric Vehicles Arthur Kerviel 1,2, Apostolos Pesyridis 1,* , Ahmed Mohammed 1 and David Chalet 2 1 Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Brunel University, London UB8 3PH, UK; [email protected] (A.K.); [email protected] (A.M.) 2 Ecole Centrale de Nantes, LHEEA Lab. (ECN/CNRS), 44321 Nantes, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-189-526-7901 Received: 17 October 2018; Accepted: 19 November 2018; Published: 3 December 2018 Abstract: Mass-produced, off-the-shelf automotive air compressors cannot be directly used for boosting a fuel cell vehicle (FCV) application in the same way that they are used in internal combustion engines, since the requirements are different. These include a high pressure ratio, a low mass flow rate, a high efficiency requirement, and a compact size. From the established fuel cell types, the most promising for application in passenger cars or light commercial vehicle applications is the proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC), operating at around 80 ◦C. In this case, an electric-assisted turbocharger (E-turbocharger) and electric supercharger (single or two-stage) are more suitable than screw and scroll compressors. In order to determine which type of these boosting options is the most suitable for FCV application and assess their individual merits, a co-simulation of FCV powertrains between GT-SUITE and MATLAB/SIMULINK is realised to compare vehicle performance on the Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP) driving cycle. -

Hydrogen As a Fuel for Gas Turbines

Hydrogen as a fuel for gas turbines A pathway to lower CO2 www.ge.com/power/future-of-energy Executive Summary In order to combat man-made climate change, there is a global need for decarbonization,* and all sectors that produce carbon dioxide (CO2) must play a role. The power sector’s journey to There are two ways to systematically have operated on fuels with at least 50% decarbonize, often referred approach the task of turning high efficiency (by volume) hydrogen. These units have gas generation into a zero or near zero- accumulated more than one million operating to as the Energy Transition, carbon resource: pre and post-combustion. hours, giving GE a unique perspective is characterized by rapid Pre-combustion refers to the systems and on the challenges of using hydrogen as deployment of renewable energy processes upstream of the gas turbine and a gas turbine fuel. resources and a rapid reduction in post-combustion refers to systems and processes downstream of the gas turbine. GE is continuing to advance the capability of coal, the most carbon-intensive The most common approach today to its gas turbine fleet to burn hydrogen through power generation source. Based tackle pre-combustion decarbonization is internally funded R&D programs and through on our extensive analysis and simple: to change the fuel, and the most US Department of Energy funded programs. experience across the breadth talked about fuel for decarbonization of the The goals of these efforts are to ensure power sector is hydrogen. that ever higher levels of hydrogen can be of the global power industry, GE burned safely and reliably in GE’s gas turbines believes that the accelerated GE is a world leader in gas turbine fuel for decades to come.