Diesel Engine Fundamentals Part 2 Course# ME406

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Investigation of Mixture Formation and Combustion in an Ethanol Direct Injection Plus Gasoline Port Injection (EDI+GPI) Engine

Investigation of Mixture Formation and Combustion in an Ethanol Direct Injection plus Gasoline Port Injection (EDI+GPI) Engine By Yuhan Huang A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Electrical, Mechanical and Mechatronic Systems Faculty of Engineering and Information Technology University of Technology Sydney December 2016 Certificate of Original Authorship This thesis is the result of a research candidature conducted jointly with another university as part of a collaborative doctoral degree. I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as part of the collaborative doctoral degree and/or fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Date: i Acknowledgements To pursue a doctoral degree could be a long and challenging journey. Through this journey, I fortunately received help and support from the following wonderful people who made this journey enjoyable and fruitful. First of all, I would like thank my principle supervisor Associate Professor Guang Hong who provided huge support and guidance. She invested numerous efforts in supervising me and always cared about my progress and future career. The experience I have acquired and research training I have received from her will greatly benefit my research career. -

High Accuracy Glow Plug-Integrated Cylinder Pressure Sensor for Closed Loop Engine Control

High Accuracy Glow Plug-Integrated Cylinder Pressure Sensor for Closed Loop Engine Control Marek T. Wlodarczyk Optrand, Inc. ABSTRACT as Homogenous Charge Compression Ignition or Premixed Charge Compression Ignition [4]-[5]. The PressureSense Glow Plug combines a miniature cylinder pressure sensor with the automotive glow plug. In diesel passenger cars and light duty trucks a The 1.7mm diameter fiber optic-based sensor is welded preferred way of introducing a cylinder pressure sensor into the glow plug heater and the signal conditioner is into a combustion chamber is through a glow plug so no encapsulated into a “smart connector” located on the top engine head modifications are required. During the of the glow plug body. The sensor offers accuracy better recent few years a number of different concepts of glow than +/-2% of reading between 220 bar and 5 bar and plugs with pressure measuring capability has been +/-0.2 to +/-0.5 bar error for pressures below 5 bar. The proposed, including designs based on piezoelectric performance of “dummy” as well as glowing and washers mounted in various glow plug places [6]-[8] or a pressure sensing devices was evaluated on various glow plug heater acting as a transfer pin in conjunction engines and over a wide range of engine operating with a piezoresistive transducer [9]. It is to be noted, conditions. however, that all these devices, which in effect measure cylinder pressure “indirectly”, share some significant INTRODUCTION performance and durability-reliability drawbacks due such factors as valve and injection actuation, engine Cylinder pressure is the fundamental engine parameter vibrations, glow plug torque effect, engine head that provides the most direct and valuable information temperature changes, vibration damage and wear of for advanced control and monitoring systems of internal moving device components, and glow plug heater combustion engines [1]. -

Steady State and Transient Efficiencies of A

STEADY STATE AND TRANSIENT EFFICIENCIES OF A FOUR CYLINDER DIRECT INJECTION DIESEL ENGINE FOR IMPLEMENTATION IN A HYBRID ELECTRIC VEHICLE A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Science Charles Van Horn August, 2006 STEADY STATE AND TRANSIENT EFFICIENCIES OF A FOUR CYLINDER DIRECT INJECTION DIESEL ENGINE FOR IMPLEMENTATION IN A HYBRID ELECTRIC VEHICLE Charles Van Horn Thesis Approved: Accepted: Advisor Department Chair Dr. Scott Sawyer Dr. Celal Batur Faculty Reader Dean of the College Dr. Richard Gross Dr. George K. Haritos Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Iqbal Husain Dr. George R. Newkome Date ii ABSTRACT The efficiencies of a four cylinder direct injection diesel engine have been investigated for the implementation in a hybrid electric vehicle (HEV). The engine was cycled through various operating points depending on the power and torque requirements for the HEV. The selected engine for the HEV is a 2005 Volkswagen 1.9L diesel engine. The 2005 Volkswagen 1.9L diesel engine was tested to develop the steady-state engine efficiencies and to evaluate the transient effects on these efficiencies. The peak torque and power curves were developed using a water brake dynamometer. Once these curves were obtained steady-state testing at various engine speeds and powers was conducted to determine engine efficiencies. Transient operation of the engine was also explored using partial throttle and variable throttle testing. The transient efficiency was compared to the steady-state efficiencies and showed a decrease from the steady- state values. -

Zenith Replacement Carburetors

not print a list price for their carburetors, each dealer can set Zenith Replacement their own prices. Check a few dealers to see who has the bet- Carburetors ter price. These referenced Zenith part numbers were supplied by by Phil Peters Mike Farmer, Application Engineer at Zenith in Bristol, VA, s a follow up to the recent reprinting of the Special where the factory is now located. The Zeniths are a newer Interest Auto article from 1977 (Fall & Winter, 2015) design universal carburetor which means they have multiple Aand the continuing requests for modern replacement fuel, choke, and throttle hook up locations. In addition, there carburetors, I have assembled the following chart of all our are air horn adaptors for modern air filters. They are com- Durant/Star/Flint/etc. engines with corresponding specifica- patible with modern ethanol fuels, have a robust inlet port, tions and replacement Zenith part numbers. As pointed out multiple venturi sizes and “back suction economizer” for part by Norm Toone and other knowledgeable members, there throttle fuel economy. were a number of errors concerning the model numbers and OEM brands in the SIA article. This chart represents The models that were picked for our engines were de- the collective input from a number of helpful members and termined by maximum air flow at 2,200 RPM for the 2 3/8” was done with engine model numbers. Car models were mounts (SAE size #1) and 2,600 RPM for the 2 11/16” not always related to calendar years. Differences in produc- mounts (SAE size #2). -

Mean Value Modelling of a Poppet Valve EGR-System

Mean value modelling of a poppet valve EGR-system Master’s thesis performed in Vehicular Systems by Claes Ericson Reg nr: LiTH-ISY-EX-3543-2004 14th June 2004 Mean value modelling of a poppet valve EGR-system Master’s thesis performed in Vehicular Systems, Dept. of Electrical Engineering at Linkopings¨ universitet by Claes Ericson Reg nr: LiTH-ISY-EX-3543-2004 Supervisor: Jesper Ritzen,´ M.Sc. Scania CV AB Mattias Nyberg, Ph.D. Scania CV AB Johan Wahlstrom,¨ M.Sc. Linkopings¨ universitet Examiner: Associate Professor Lars Eriksson Linkopings¨ universitet Linkoping,¨ 14th June 2004 Avdelning, Institution Datum Division, Department Date Vehicular Systems, Dept. of Electrical Engineering 14th June 2004 581 83 Linkoping¨ Sprak˚ Rapporttyp ISBN Language Report category — ¤ Svenska/Swedish ¤ Licentiatavhandling ISRN ¤ Engelska/English ££ ¤ Examensarbete LITH-ISY-EX-3543-2004 ¤ C-uppsats Serietitel och serienummer ISSN ¤ D-uppsats Title of series, numbering — ¤ ¤ Ovrig¨ rapport ¤ URL for¨ elektronisk version http://www.vehicular.isy.liu.se http://www.ep.liu.se/exjobb/isy/2004/3543/ Titel Medelvardesmodellering¨ av EGR-system med tallriksventil Title Mean value modelling of a poppet valve EGR-system Forfattare¨ Claes Ericson Author Sammanfattning Abstract Because of new emission and on board diagnostics legislations, heavy truck manufacturers are facing new challenges when it comes to improving the en- gines and the control software. Accurate and real time executable engine models are essential in this work. One successful way of lowering the NOx emissions is to use Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR). The objective of this thesis is to create a mean value model for Scania’s next generation EGR system consisting of a poppet valve and a two stage cooler. -

Small Engine Parts and Operation

1 Small Engine Parts and Operation INTRODUCTION The small engines used in lawn mowers, garden tractors, chain saws, and other such machines are called internal combustion engines. In an internal combustion engine, fuel is burned inside the engine to produce power. The internal combustion engine produces mechanical energy directly by burning fuel. In contrast, in an external combustion engine, fuel is burned outside the engine. A steam engine and boiler is an example of an external combustion engine. The boiler burns fuel to produce steam, and the steam is used to power the engine. An external combustion engine, therefore, gets its power indirectly from a burning fuel. In this course, you’ll only be learning about small internal combustion engines. A “small engine” is generally defined as an engine that pro- duces less than 25 horsepower. In this study unit, we’ll look at the parts of a small gasoline engine and learn how these parts contribute to overall engine operation. A small engine is a lot simpler in design and function than the larger automobile engine. However, there are still a number of parts and systems that you must know about in order to understand how a small engine works. The most important things to remember are the four stages of engine operation. Memorize these four stages well, and everything else we talk about will fall right into place. Therefore, because the four stages of operation are so important, we’ll start our discussion with a quick review of them. We’ll also talk about the parts of an engine and how they fit into the four stages of operation. -

117001 Tiertwo Cp6 14.Pdf

This is what it takes to be a PRO. Performance enhancing features like a heavy-duty air cleaner, forged-steel crankshaft, electronic ignition and cast-iron cylinder liner. KOHLER® Command PRO® is the standard for professional-grade power and performance. COURAGE XT COMMAND PRO® DEPENDABLE OPERATI COURAGE SINGLE ON • Quad-Clean ™ all-season four-stage cyclonic air filter – effective COURAGE TWINS engine protection for tough-and-dirty conditions. COURAGE XT • Protects from airborne contaminants that can easily clog COURAGE PRO TWINS COMMAND PRO® traditional air filters. LoNGER RUN TIMES COURAGE SINGLE • Large-capacity fuel tank means more time working, less time filling. COURAGE XT COURAGE TWINS • Electronic ignition and an advanced combustion system design help COMMAND PRO® reduce fuel consumption. COURAGE PRO TWINS COURAGE XT EASIER REPOWERING COURAGE SINGLE COMMAND PRO® • Power or repower your equipment without expensive modifications. COURAGE TWINS ALL-WEATHER P COURAGE SINGLE ERFORMANCE COURAGE PRO TWINS • Quad-Clean air filter reconfigures in seconds to recycle engine heat. COURAGE XT COURAGE TWINS • Command PRO starts effortlessly in all weather conditions, from COMMAND PRO® 0 to 110 degrees. COURAGE PRO TWINS BUILT TO LAST COURAGE SINGLE • Forged-steel crankshafts and tough Stellite ®-faced exhaust valves with COURAGE TWINS Tufftride ®-coated stems and cast-iron cylinder bores. • Oil Sentry ™ automatically shuts engine down in low-oil conditions. COURAGE PRO TWINS 6-HP HORIZONTAL-SHAFT ENGINES 6-HP HORIZONTAL-SHAFT ENGINES TOP VIEW -

SV470-SV620 Service Manual

SV470-SV620 Service Manual IMPORTANT: Read all safety precautions and instructions carefully before operating equipment. Refer to operating instruction of equipment that this engine powers. Ensure engine is stopped and level before performing any maintenance or service. 2 Safety 3 Maintenance 5 Specifi cations 13 Tools and Aids 16 Troubleshooting 20 Air Cleaner/Intake 21 Fuel System 31 Governor System 33 Lubrication System 35 Electrical System 44 Starter System 47 Emission Compliant Systems 50 Disassembly/Inspection and Service 63 Reassembly 20 690 01 Rev. F KohlerEngines.com 1 Safety SAFETY PRECAUTIONS WARNING: A hazard that could result in death, serious injury, or substantial property damage. CAUTION: A hazard that could result in minor personal injury or property damage. NOTE: is used to notify people of important installation, operation, or maintenance information. WARNING WARNING CAUTION Explosive Fuel can cause Accidental Starts can Electrical Shock can fi res and severe burns. cause severe injury or cause injury. Do not fi ll fuel tank while death. Do not touch wires while engine is hot or running. Disconnect and ground engine is running. Gasoline is extremely fl ammable spark plug lead(s) before and its vapors can explode if servicing. CAUTION ignited. Store gasoline only in approved containers, in well Before working on engine or Damaging Crankshaft ventilated, unoccupied buildings, equipment, disable engine as and Flywheel can cause away from sparks or fl ames. follows: 1) Disconnect spark plug personal injury. Spilled fuel could ignite if it comes lead(s). 2) Disconnect negative (–) in contact with hot parts or sparks battery cable from battery. -

Finite Element Analysis of a Car Rocker Arm

Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Operations Excellence and Service Engineering Orlando, Florida, USA, September 10-11, 2015 Finite element analysis of a car rocker arm Tawanda Mushiri D.Eng. Student; University of Johannesburg, Department of Mechanical Engineering, P. O. Box 524, Auckland Park 2006, South Africa. [email protected] Lecturer; University of Zimbabwe, Department of Mechanical Engineering, P.O Box MP167, Mt Pleasant, Harare Charles Mbohwa Professor and Supervisor; University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park Bunting Road Campus, P. O. Box 524, Auckland Park 2006, Room C Green 5, Department of Quality and Operations Management, Johannesburg, South Africa. [email protected] Abstract High Density Polyethylene (HDPE) composite rocker arm has been considered for analysis owing to its light weight, higher strength and good frictional characteristics. A 3-D finite element analysis was carried out to find out the maximum stresses developed in the rocker arms made of steel and composite. From the results it was noted that almost same stresses are developed for both the materials (steel and the composite). With this it may be concluded that the stresses developed in the composite is well within the limits without failure. Therefore the proposed composite may be considered as an alternate material for steel to be used as rocker arm. Keywords High Density Polyethylene (HDPE), Rocker arm, finite element, modelling, simulation, steel, composite 1.0: Introduction A rocker arm is an oscillating lever that conveys radial movement from the cam lobe into linear movement at the poppet valve to open it. One end is raised and lowered by a rotating lobe of the camshaft (either directly or via a tappet (lifter) and pushrod) while the other end acts on the valve stem. -

A Method of Fuel Testing in a CFR Engine

Scholars' Mine Masters Theses Student Theses and Dissertations 1960 A method of fuel testing in a CFR engine George R. Baumgartner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses Part of the Mechanical Engineering Commons Department: Recommended Citation Baumgartner, George R., "A method of fuel testing in a CFR engine" (1960). Masters Theses. 5575. https://scholarsmine.mst.edu/masters_theses/5575 This thesis is brought to you by Scholars' Mine, a service of the Missouri S&T Library and Learning Resources. This work is protected by U. S. Copyright Law. Unauthorized use including reproduction for redistribution requires the permission of the copyright holder. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A METHOD OF FUEL TESTING IN A CFR ENGINE BY GEORGE R. BAUMGARTNER ----~--- A THESIS submitted to the faculty of the SCHOOL OF MINES AND METALLURGY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI in partial fulfillment of the work required for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MECHANICAL ENGINEERING Rolla, Missouri 1960 _____ .. ____ .. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author would like to express his appreciation to Dr. A. J• Miles, Chairman of tho Mechanical Engineering Department, and Professor G. L. Scofield, Mechanical Engineering Department, for their guidance and interest in this investigation. Thanks are also dua Mr. Douglas Kline for his constant assistance while conducting the tests. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgement •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• ii Contents•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••o•••••••••• -

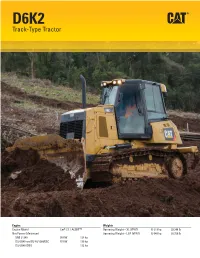

Large Specalog for D6K2 Track-Type Tractor, AEHQ7228-01

D6K2 Track-Type Tractor Engine Weights Engine Model Cat® C7.1 ACERT™ Operating Weight – XL (VPAT) 13 311 kg 29,346 lb Net Power (Maximum) Operating Weight – LGP (VPAT) 13 948 kg 30,750 lb SAE J1349 95 kW 128 hp ISO 9249 and EU 80/1269/EEC 97 kW 130 hp ISO 9249 (DIN) 132 hp D6K2 Features Powerful Productivity Boost your productivity with the new Stable Blade Control feature, dozer and undercarriage. Eco Modes and Auto Engine Speed Control help reduce overall fuel use. Experience maneuverability, precision and response, from the hydrostatic power train, power turn capability and standard electro-hydraulic controls. Comfortable Operator Station Work longer with less fatigue in the spacious and comfortable cab. The D6K2 is easy to handle and includes features that help your operators be more productive. Integrated Technologies Maximize utilization and control costs with the Cat Product Link™. AccuGrade™ Ready Option means easy installation of the performance enhancing Cat AccuGrade system. Serviceability and Customer Support Easy service, reliability and Cat dealer expertise keep you working and help to reduce overall costs. Contents Operator Station..................................................4 Ergonomic Controls ............................................5 Stable Blade Control...........................................5 Power Train ..........................................................6 Fuel Economy.......................................................6 Undercarriage .....................................................7 Integrated -

Subject: Supplement to Upper Engine and Fuel Injector Cleaner Label Models: All GM Vehicles Equipped with a Gasoline Engine

7/11/2018 #PIP4753: Supplement To Upper Engine And Fuel Injector Cleaner Label - (Dec 11, 2009) • 2003 GMC Truck Yukon 4WD • MotoLogic 2003 Yukon 4WD Report a problem with this article Subject: Supplement to Upper Engine and Fuel Injector Cleaner Label All GM Vehicles Models: Equipped with a Gasoline Engine The following diagnosis might be helpful if the vehicle exhibits the symptom(s) described in this PI. Condition/Concern: Some service procedures, service bulletins, or PIs may advise to decarbon the engine with GM Upper Engine and Fuel Injector Cleaner to remove valve deposits but the label that is on the back of the bottle does not include any instructions that explain how to use the cleaner. Recommendation/Instructions: If a service procedure, service bulletin, or PI does not include decarboning instructions and the GM Vehicle Care 3 Step Induction Cleaning Kit (E-957-001) is not available, the guidelines below supplement the label and explain how the cleaner can be used to clean the intake valves: Important: Extreme care must be taken not to hydrolock the engine when inducing the cleaner. If too much cleaner is induced at too low of a RPM, or if you force the engine to stall by inducing too much cleaner at once, the engine may hydrolock and bend a connecting rod(s). 1. In a well-ventillated area with the engine at operating temperature, slowly/carefully induce a bottle of GM Upper Engine and Fuel Injection Cleaner into the engine with RPM off of idle enough to prevent it from stalling (typically around 2,000 RPM or so).