COUNTRY ANALYSIS Developing Capacities for Trade Integration and Economic Diversification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Audit Chamber the Report of the Auditor

NATIONAL AUDIT CHAMBER THE REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT OF SOUTHERN SUDAN FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2008 TO THE PRESIDENT THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN AND SOUTH SUDAN NATIONAL LEGISLATIVEASSEMBLY 1 2 CONTENTS Auditor General’s Opinion 7 Financial Statements for 2008 18 Chapter – 1 : Oil Revenue 75 Chapter – 2 : Non- Oil Revenue 89 Chapter – 3 : Ministry of Cabinet Affairs 97 Chapter – 4 : Ministry of Commerce, Trade &Supply 105 Chapter – 5 : Ministry of Education, Science and Technology 117 Chapter – 6 : Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning 133 Chapter – 7 : Ministry of Health 153 Chapter – 8 : Ministry of Internal Affairs 173 Chapter – 9 : Judiciary 191 Chapter – 10 : Ministry of Legal Affairs and Constitutional 203 Development Chapter – 11 : Southern Sudan Legislative Assembly 213 Chapter – 12 :Ministry of Sudan People’s Liberation Army 233 Affairs Chapter – 13 : Southern Sudan Electricity Commission 255 Chapter – 14 : Southern Sudan Human Rights Commission 267 3 4 SOUTH SUDAN NATIONAL AUDIT CHAMBER AUDITOR GENERAL’S OPINION ON GOVERNMENT OF SOUTHERN SUDAN FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF 2008 5 6 SOUTH SUDAN NATIONAL AUDIT CHAMBER OPINION OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2008 1. INTRODUCTION The year 2008 was the fourth fiscal cycle of the Government of Southern Sudan. The Financial Statements for 2008 were issued in January 2012 and hence the late presentation. The audit of the Financial Statements of 2008 was conducted in 2012. Government Ministries and Agencies were more responsive to audit than in previous years. I thank the President for his helpful phone calls on this matter. -

South Sudan's Financial Sector

South Sudan’s Financial Sector Bank of South Sudan (BSS) Presentation Overview . Main messages & history/perspectives . Current state of the industry . Key issues – regulations, capitalization, skills, diversification, inclusion . The way forward “The road is under construction” Main Messages & History/perspectives . The history of financial institutions in South Sudan is a short one. Throughout Khartoum rule till the end of civil war in 2005, there were very few commercial banks concentrated in Juba, Wau and Malakal. South Sudanese were deliberately excluded from the economic system. As a result 90% of the population in South Sudan were not exposed to banking services . Access to finance was limited to Northern traders operating in Southern Sudan. In February 2008, Islamic banks left the South since the Bank of Southern Sudan(BOSS) introduced conventional banking . However, after the CPA the Bank of Southern Sudan, although a mere branch of the central bank of Sudan took a bold step by licensing local and expatriate banks that took interest to invest in South Sudan. South Sudan needs a stable, well diversified financial sector providing the right kinds of products and services with a level of intermediation and inclusion to support the country’s ambitions Current State of the Sector As of November 2013 . 28 Commercial Banks are now operating in South Sudan and more than 70 applications on the pipeline . 10 Micro Finance Institutions . 86 Forex Bureaus . A handful of Insurance companies Current state of the Sector (2) . Despite the increased number of financial institutions, competition is still limited and services are mainly concentrated in the urban hubs . -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

1 AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O

AU Commission of Inquiry on South Sudan Addis Ababa, Ethiopia P. O. Box 3243 Telephone: +251 11 551 7700 / +251 11 518 25 58/ Ext 2558 Website: http://www.au.int/en/auciss Original: English FINAL REPORT OF THE AFRICAN UNION COMMISSION OF INQUIRY ON SOUTH SUDAN ADDIS ABABA 15 OCTOBER 2014 1 Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................... 5 CHAPTER I ..................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 8 CHAPTER II .................................................................................................................. 34 INSTITUTIONS IN SOUTH SUDAN .............................................................................. 34 CHAPTER III ............................................................................................................... 110 EXAMINATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS AND OTHER ABUSES DURING THE CONFLICT: ACCOUNTABILITY ......................................................................... 111 CHAPTER IV ............................................................................................................... 233 ISSUES ON HEALING AND RECONCILIATION ....................................................... -

River Nile Politics: the Role of South Sudan

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI INSTITUTE OF DIPLOMACY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES RIVER NILE POLITICS: THE ROLE OF SOUTH SUDAN R52/68513/2013 MATARA JAMES KAMAU A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE AWARD OF A DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT MANAGEMENT. OCTOBER 2015 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been submitted for another Degree in any other University Signature ……………………………..…Date……………………………………. Matara James Kamau, R52/68513/2013 This research project has been submitted for examination with my permission as the University supervisor Signature………………………………...Date…………………………………… Prof. Maria Nzomo ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, all thanks to God Almighty for the strength and ability to pursue this degree. For without him, there would be no me. I wish to express my sincere thanks to Professor Maria Nzomo the research supervisor for her tireless effort and professional guidance in making this project a success. I also extend my deepest gratitude to entire university academic staff in particular those working in the Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this research project to my entire Matara‘s family for moral and financial support during the time of research iv ABSTRACT This study focused on River Nile Politics, a study of the role of South Sudan. The study relates to the emergence of a new state amongst existing riparian states and how this may resonate with trans-boundary conflicts. The independence of South Sudan has been revealed in this study to have a mixture of unanswered questions. The study is grounded on Collier- Hoeffer theory analysed the trans-boundary conflict based on the framework of many variable including: identities, economics, religion and social status in the Nile basin. -

South Sudan Rapid Response Ebola 2019

RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS YEAR: 2019 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS SOUTH SUDAN RAPID RESPONSE EBOLA 2019 19-RR-SSD-33820 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR ALAIN NOUDÉHOU REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After-Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. 10 October 2019 The AAR took place on 10 October 2019, with the participation of WHO, UNICEF, IOM, WFP, and the Ebola Secretariat (EVD Secretariat). b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report on the Yes No use of CERF funds was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team. The report was not discussed within the Humanitarian Country Team due to time constraints; however, they received a draft of the completed report for their review and comment as of the 25 October 2019. c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant Yes No government counterparts)? The final version of the RC/HC report was shared with CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, as well as with cluster coordinators and the EVD Secretariat, as of 16 October 2019. 2 PART I Strategic Statement by the Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator South Sudan is considered to be one of the countries neighbouring the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) at highest risk of Ebola importation and transmission. Thanks to the allocation of USD $2.1 million from the Central Emergency Relief Fund Ebola preparedness in South Sudan, including the capacity to detect and respond to Ebola, has been strengthened. -

Knowing No Fear

United Nations Mission May 2010 In BBC presenter SUDANZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi Knowing no fear Published by UNMIS Public Information Office INSIDE 3 Special Focus: BUSINESS 17 April: The European Union Observer’s mission • Mummies, medicine and Coca Cola and Carter Centre issued separate preliminary Diary statements on Sudanese elections, saying they • Everywhere a bank paved the way for democratic progress and • Reeling in shared profit constituted a Comprehensive Peace Agreement benchmark, although they fell short • Doing business in Abou Shouk of international standards on the whole. The African Union Observer Mission said the • One block at a time elections, though imperfect, were historically significant and an important milestone • From guns to goods in the country’s peace and democratization process. Congratulating the Sudanese people, the League of Arab States Observer Mission hoped the elections would be a 9 Transport catalyst for further democratic transformation and development. Levelling Juba roads 18 April: UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Sudan Georg Charpentier warned that 10 Profile: Zeinab Badawi continued instability in parts of the eastern Jebel Marra area in Darfur had prevented agencies from accessing areas where they had been providing aid, including food, Knowing no fear water, and medicines, over the past five years. 11 Secretary-General’s report 26 April: Announcing preliminary results for Sudan’s elections, the National Ban calls for referenda preparations Elections Commission (NEC) declared that National Congress Party candidate Omar Al Bashir had topped the poll for President of Sudan with 68.2 per cent of the vote. -

Boating on the Nile

United Nations Mission September 2010 InSUDAN Boating on the Nile Published by UNMIS Public Information Office INSIDE 8 August: Meeting with Minister of Humanitarian Affairs Mutrif Siddiq, Joint Special Representative for Darfur 3 Special Focus: Transport Ibrahim Gambari expressed regrets on behalf of the • On every corner Diary African Union-UN Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) over • Boating on the Nile recent events in Kalma and Hamadiya internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in • Once a lifeline South Darfur and their possible negative impacts on the future of the peace process. • Keeping roads open • Filling southern skies 9 August: Blue Nile State members of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and National Congress Party (NCP) formed a six-member parliamentary committee charged with raising awareness about popular consultations on Comprehensive Peace Agreement 10 Photo gallery implementation in the state. The Sufi way 10 August: The SPLM and NCP began pre-referendum talks on wealth and power-sharing, 12 Profile demarcating the border, defining citizenship and sharing the Nile waters in preparation for the Knowledge as food southern self-determination vote, scheduled for 9 January 2011. 14 August: Two Jordanian police advisors with UNAMID were abducted in Nyala, Southern Darfur, 13 Environment as they were walking to a UNAMID transport dispatch point 100 meters from their residence. Reclaiming the trees Three days later the two police advisors were released unharmed in Kass, Southern Darfur. 14 Communications 16 August: Members of the Southern Sudan Human Rights Commission elected a nine-member The voice of Miraya steering committee to oversee its activities as the region approaches the self-determination referendum three days later the two police advisor were released unharmed in Kass, Southern Darfur. -

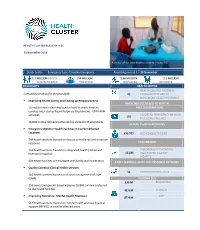

SS HC Bulletin Nov 2018.Pdf (English)

HEALTH CLUSTER BULLETIN # 11 30 November 2018 A clinical officer attending to a patient. Photo: IHO. South Sudan Emergency type: Complex Emergency Reporting period: 1 – 30 November 5.1 MILLION PEOPLE 2.4 MILLION 1.96 MILLION 2.1 MILLION IN HEALTH NEED TARGETED DISPLACED REFUGEES HIGHLIGHTS HEALTH SECTOR HEALTH CLUSTER PARTNERS Cumulative analysis for the year 2018 43 EARMARKED IN HRP TO IMPLEMENT HEALTH RESPONSE . Improving Health Access and Scaling up Responsiveness MEDICINES DELIVERED TO HEALTH 18 mobile teams were deployed in hard to reach areas to FACILITIES/PARTNERS conduct Inter-cluster Rapid Response Mechanisms- ICRM-RRM activities. ASSORTED EMERGENCY MEDICAL 101 KITS (CORE PIPELINE) 16,898 normal deliveries attended by skilled birth attendants. HEALTH CLUSTER ACTIVITIES . Emergency WASH in Health Facilities in Conflict Affected Locations 476 777 OPD CONSULTATIONS 749 health workers trained on disease surveillance and outbreak response. VACCINATION 142 health workers trained on integrated health (WASH and CHILDREN (6-59 MONTHS) Nutrition) response. 16 286 VACCINATED AGAINST MEASLES 404 health facilities are equipped with functional incinerators. EARLY WARNING ALERT AND RESPONSE NETWORK . Quality Essential Clinical Health Services . 41 EWARN SENTINEL SITES 182 health workers trained on clinical management of rape (CMR). FUNDING $US 130 M REQUESTED 259 sexual and gender based violence (SGBV) survivors referred to the health facilities. 42.6 M FUNDED . Improving Resilience- Mental Health Response GAP 87.4 M 514 health workers trained on mental health and psychosocial support (MPHSS) in conflict affected areas. Key Context Update . A joint EVD external monitoring team assessed the country’s EVD preparedness and response status. The team completed the consolidated preparedness checklist and road map with the next steps. -

Mining in South Sudan: Opportunities and Risks for Local Communities

» REPORT JANUARY 2016 MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF SMALL-SCALE AND ARTISANAL GOLD MINING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EQUATORIA STATES, SOUTH SUDAN MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN FOREWORD We are delighted to present you the findings of an assessment conducted between February and May 2015 in two states of South Sudan. With this report, based on dozens of interviews, focus group discussions and community meetings, a multi-disciplinary team of civil society and government representatives from South Sudan are for the first time shedding light on the country’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector. The picture that emerges is a remarkable one: artisanal gold mining in South Sudan ‘employs’ more than 60,000 people and might indirectly benefit almost half a million people. The vast majority of those involved in artisanal mining are poor rural families for whom alluvial gold mining provides critical income to supplement their subsistence livelihood of farming and cattle rearing. Ostensibly to boost income for the cash-strapped government, artisanal mining was formalized under the Mining Act and subsequent Mineral Regulations. However, owing to inadequate information-sharing and a lack of government mining sector staff at local level, artisanal miners and local communities are not aware of these rules. In reality there is almost no official monitoring of artisanal or even small-scale mining activities. Despite the significant positive impact on rural families’ income, the current form of artisanal mining does have negative impacts on health, the environment and social practices. With most artisanal, small-scale and exploration mining taking place in rural areas with abundant small arms and limited presence of government security forces, disputes over land access and ownership exacerbate existing conflicts. -

Sudan Agricultural Enterprise Finance Program Final Report

SUDAN AGRICULTURAL ENTERPRISE FINANCE PROGRAM FINAL REPORT APRIL 30, 2008 This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. It was prepared by Chemonics International Inc. SUDAN AGRICULTURAL ENTERPRISE FINANCE PROGRAM FINAL REPORT Contract No. 623-C-00-02-00087-00 The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. CONTENTS Acronyms ............................................................................................................................v Executive Summary ............................................................................................................1 Section I: The Country Context ..........................................................................................3 Section II: The AEFP Approach .........................................................................................4 Section III: Project Overview .............................................................................................6 Section IV: Establishing SUMI ........................................................................................10 Section V: Building SUMI’s Capacity .............................................................................14 Section VI: Geographic Expansion....................................................................................20 Section VII: New Product Development ..........................................................................25 -

Peace Is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp By

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT PEACE IS THE NAME OF OUR CATTLE-CAMP LOCAL RESPONSES TO CONFLICT IN EASTERN LAKES STATE, SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT Peace is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp Local responses to conflict in Eastern Lakes State, South Sudan JOHN RYLE AND MACHOT AMUOM Authors John Ryle (co-author), Legrand Ramsey Professor of Anthropology at Bard College, New York, was born and educated in the United Kingdom. He is lead researcher on the RVI South Sudan Customary Authorities Project. Machot Amuom Malou (co-author) grew up in Yirol during Sudan’s second civil war. He is a graduate of St. Lawrence University, Uganda, and a member of The Greater Yirol Youth Union that organised the 2010 Yirol Peace Conference. Abraham Mou Magok (research consultant) is a graduate of the Nile Institute of Management Studies in Uganda. Born in Aluakluak, he has worked in local government and the NGO sector in Greater Yirol. Aya piŋ ëë kͻcc ἅ luël toc ku wεl Ɣͻk Ɣͻk kuek jieŋ ku Atuot akec kaŋ thör wal yic Yeŋu ye köc röt nͻk wεt toc ku wal Mith thii nhiar tͻͻŋ ku ran wut pεεc Yin aci pεεc tik riεl Acin ke cam riεlic Kͻcdit nyiar tͻͻŋ Ku cͻk ran nͻk aci yͻk thin Acin ke cam riεlic Wut jiëŋ ci riͻc Wut Atuot ci riͻc Yok Ɣen Apaak ci riͻc Yen ya wutdie Acin kee cam riεlic ëëë I hear people are fighting over grazing land. Cattle don’t fight—neither Jieŋ cattle nor Atuot cattle. Why do we fight in the name of grass? Young men who raid cattle-camps— You won’t get a wife that way.