Public Private Cooperation Fragile States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Sudan Country Portfolio

South Sudan Country Portfolio Overview: Country program established in 2013. USADF currently U.S. African Development Foundation Partner Organization: Foundation for manages a portfolio of 9 projects and one Cooperative Agreement. Tom Coogan, Regional Director Youth Initiative Total active commitment is $737,000. Regional Director Albino Gaw Dar, Director Country Strategy: The program focuses on food security and Email: [email protected] Tel: +211 955 413 090 export-oriented products. Email: [email protected] Grantee Duration Value Summary Kanybek General Trading and 2015-2018 $98,772 Sector: Agro-Processing (Maize Milling) Investment Company Ltd. Location: Mugali, Eastern Equatoria State 4155-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to build Kanybek’s capacity in business and financial management. The funds will also build technical capacity by providing training in sustainable agriculture and establishing a small milling facility to process raw maize into maize flour. Kajo Keji Lulu Works 2015-2018 $99,068 Sector: Manufacturing (Shea Butter) Multipurpose Cooperative Location: Kajo Keji County, Central Equatoria State Society (LWMCS) Summary: The project funds will be used to develop LWMCS’s capacity in financial and 4162-SSD business management, and to improve its production capacity by establishing a shea nut purchase fund and purchasing an oil expeller and related equipment to produce grade A shea butter for export. Amimbaru Paste Processing 2015-2018 $97,523 Sector: Agro-Processing (Peanut Paste) Cooperative Society (APP) Location: Loa in the Pageri Administrative Area, Eastern Equatoria State 4227-SSD Summary: The project funds will be used to improve the business and financial management of APP through a series of trainings and the hiring of a management team. -

National Audit Chamber the Report of the Auditor

NATIONAL AUDIT CHAMBER THE REPORT OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF THE GOVERNMENT OF SOUTHERN SUDAN FOR THE FINANCIAL YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2008 TO THE PRESIDENT THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN AND SOUTH SUDAN NATIONAL LEGISLATIVEASSEMBLY 1 2 CONTENTS Auditor General’s Opinion 7 Financial Statements for 2008 18 Chapter – 1 : Oil Revenue 75 Chapter – 2 : Non- Oil Revenue 89 Chapter – 3 : Ministry of Cabinet Affairs 97 Chapter – 4 : Ministry of Commerce, Trade &Supply 105 Chapter – 5 : Ministry of Education, Science and Technology 117 Chapter – 6 : Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning 133 Chapter – 7 : Ministry of Health 153 Chapter – 8 : Ministry of Internal Affairs 173 Chapter – 9 : Judiciary 191 Chapter – 10 : Ministry of Legal Affairs and Constitutional 203 Development Chapter – 11 : Southern Sudan Legislative Assembly 213 Chapter – 12 :Ministry of Sudan People’s Liberation Army 233 Affairs Chapter – 13 : Southern Sudan Electricity Commission 255 Chapter – 14 : Southern Sudan Human Rights Commission 267 3 4 SOUTH SUDAN NATIONAL AUDIT CHAMBER AUDITOR GENERAL’S OPINION ON GOVERNMENT OF SOUTHERN SUDAN FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF 2008 5 6 SOUTH SUDAN NATIONAL AUDIT CHAMBER OPINION OF THE AUDITOR GENERAL ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31ST DECEMBER 2008 1. INTRODUCTION The year 2008 was the fourth fiscal cycle of the Government of Southern Sudan. The Financial Statements for 2008 were issued in January 2012 and hence the late presentation. The audit of the Financial Statements of 2008 was conducted in 2012. Government Ministries and Agencies were more responsive to audit than in previous years. I thank the President for his helpful phone calls on this matter. -

![Visit to Terekeka [Oct 2020]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9639/visit-to-terekeka-oct-2020-339639.webp)

Visit to Terekeka [Oct 2020]

Visit to Terekeka and St Stephen’s School, South Sudan – 17th – 18th March 2020 Report by Mike Quinlan Introduction Following my participation in a SOMA (Sharing of Ministries Abroad) Mission to the Internal Province of Jonglei from 7th to 16th March, I was able to make a short visit to Terekeka and to St Stephen’s School escorted by the Bishop of Terekeka, Rt Rev Paul Moji Fajala. Bp Paul met me at my hotel in Juba and drove me to Terekeka on the morning of Tuesday 17th March. We visited St Stephen’s School and I also saw some of the other sights of Terekeka (mainly boats on the bank of the Nile). Bp Paul also took me to see his house in Terekeka. After a night at a comfortable hotel, which had electricity and a fan in the evening, Bp Paul drove me back to Juba on the morning of Wednesday 18th March. I was privileged to be taken to meet the Primate of the Episcopal Church of South Sudan (ECSS), Most Rev Justin Badi Arama at his office. ABp Justin is also the chair of SOMA’s International Council. Bp Paul also took me to his house in Juba, where I met his wife, Edina, and had lunch before he took me to the airport to catch my flight back to UK. Terekeka is a small town about 75km north of Juba on the west bank of the White Nile. It takes about two and a half hours to drive there from Juba on a dirt road that becomes very difficult during the rainy season. -

Urban Displacement and Vulnerability in Yei, South Sudan

Sanctuary in the city? Urban displacement and vulnerability in Yei, South Sudan Ellen Martin and Nina Sluga HPG Working Paper December 2011 Overseas Development Institute 111 Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7JD United Kingdom Tel: +44(0) 20 7922 0300 Fax: +44(0) 20 7922 0399 Website: www.odi.org.uk/hpg Email: [email protected] hpg Humanitarian Policy Group 134355_Sanctuary in the City - YEI Cover 1_OUTER 134355_Sanctuary intheCity-YEICover1_INNER About the authors Ellen Martin is a Research Officer in the Humanitarian Policy Group (HPG). Nina Sluga was Country Analyst (CAR, Chad, Congo, Sudan and South Sudan) for the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) at the time of writing of this report. Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the staff of NRC in Juba and Yei for their logistical support during the planning of this study, and staff in the GIZ office in Yei for sharing their baseline studies. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the many people who contributed in numerous ways to the study, including research support and the provision of documents and materials and reviewing drafts. Particular thanks to Simon Russell (UNHRC), Charles Mballa (UNHCR), Gregory Norton (IDMC), Nina Birkeland (IDMC), Marzia Montemurro (IDMC) and Sara Pantuliano (HPG). Wendy Fenton (HPN) provided extremely valuable input into the initial draft. Thanks too to Matthew Foley for his expert editing of the report. Finally, we are especially grateful to the many people in Yei who generously gave their time to take part in this study. This study was carried out in collaboration with the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC). -

Population Mobility Mapping (Pmm) South Sudan: Ebola Virus Disease (Evd) Preparedness

POPULATION MOBILITY MAPPING (PMM) SOUTH SUDAN: EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE (EVD) PREPAREDNESS CONTEXT The 10th EVD outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is still ongoing, with a total of 3,428 EVD cases reported as of 2 February 2020, including 3,305 confirmed and 118 probable cases. A total of 2,250 deaths have been reported, with a case fatality ratio (CFR) of 65.6%. Although the rate of new cases in DRC has decreased and stabilized, two health zones reported 25 new confirmed cases within the 21-day period from 13 January to 2 February 2019: Beni (n=18) and Mabalako (n=30).1 The EVD outbreak in DRC is the 2nd largest in history and is affecting the north-eastern provinces of the country, which border Uganda, Rwanda and South Sudan. South Sudan, labeled a 'priority 1' preparedness country, has continued to scale up preparedeness efforts since the outbreak was confirmed in Kasese district in South Western Uganda on 11 June 2019 and in Ariwara, DRC (70km from the South Sudan border) on 30 June 2019. South Sudan remains at risk while there is active transmission in DRC, due to cross-border population movements and a weak health system. To support South Sudan’s Ministry of Health and other partners in their planning for EVD preparedness, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has applied its Population Mobility Mapping (PMM) approach to inform the prioritization of locations for preparedness activities. Aim and Objectives The aim of PMM in South Sudan is to inform the 2020 EVD National Preparedness Plan by providing partners with relevant information on population mobility and cross-border movements. -

Local Needs and Agency Conflict: a Case Study of Kajo Keji County, Sudan

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 11, Issue 1 | Fall 2009 Local Needs and Agency Conflict: A Case Study of Kajo Keji County, Sudan RANDALL FEGLEY Abstract: During Southern Sudan’s second period of civil war, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) provided almost all of the region’s public services and greatly influenced local administration. Refugee movements, inadequate infrastructures, food shortages, accountability issues, disputes and other difficulties overwhelmed both the agencies and newly developed civil authorities. Blurred distinctions between political and humanitarian activities resulted, as demonstrated in a controversy surrounding a 2004 distribution of relief food in Central Equatoria State. Based on analysis of documents, correspondence and interviews, this case study of Kajo Keji reveals many of the challenges posed by NGO activity in Southern Sudan and other countries emerging from long-term instability. Given recurrent criticisms of NGOs in war-torn areas of Africa, agency operations must be appropriately geared to affected populations and scrutinized by governments, donors, recipients and the media. A Critique of NGO Operations Once seen as unquestionably noble, humanitarian agencies have been subject to much criticism in the last 30 years.1 This has been particularly evident in the Horn of Africa. Drawing on experience in Ethiopia, Hancock depicted agencies as bureaucracies more intent on keeping themselves going than helping the poor.2 Noting that aid often allowed despots to maintain power, enrich themselves and escape responsibility, he criticized their tendency for big, wasteful projects using expensive experts who bypass local concerns and wisdom and do not speak local languages. He accused their personnel of being lazy, over-paid, under-educated and living in luxury amid their impoverished clients. -

South Sudan Rapid Response Ebola 2019

RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS YEAR: 2019 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR REPORT ON THE USE OF CERF FUNDS SOUTH SUDAN RAPID RESPONSE EBOLA 2019 19-RR-SSD-33820 RESIDENT/HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR ALAIN NOUDÉHOU REPORTING PROCESS AND CONSULTATION SUMMARY a. Please indicate when the After-Action Review (AAR) was conducted and who participated. 10 October 2019 The AAR took place on 10 October 2019, with the participation of WHO, UNICEF, IOM, WFP, and the Ebola Secretariat (EVD Secretariat). b. Please confirm that the Resident Coordinator and/or Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) Report on the Yes No use of CERF funds was discussed in the Humanitarian and/or UN Country Team. The report was not discussed within the Humanitarian Country Team due to time constraints; however, they received a draft of the completed report for their review and comment as of the 25 October 2019. c. Was the final version of the RC/HC Report shared for review with in-country stakeholders (i.e. the CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, cluster/sector coordinators and members and relevant Yes No government counterparts)? The final version of the RC/HC report was shared with CERF recipient agencies and their implementing partners, as well as with cluster coordinators and the EVD Secretariat, as of 16 October 2019. 2 PART I Strategic Statement by the Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator South Sudan is considered to be one of the countries neighbouring the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) at highest risk of Ebola importation and transmission. Thanks to the allocation of USD $2.1 million from the Central Emergency Relief Fund Ebola preparedness in South Sudan, including the capacity to detect and respond to Ebola, has been strengthened. -

Knowing No Fear

United Nations Mission May 2010 In BBC presenter SUDANZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi ZeinabBadawi Knowing no fear Published by UNMIS Public Information Office INSIDE 3 Special Focus: BUSINESS 17 April: The European Union Observer’s mission • Mummies, medicine and Coca Cola and Carter Centre issued separate preliminary Diary statements on Sudanese elections, saying they • Everywhere a bank paved the way for democratic progress and • Reeling in shared profit constituted a Comprehensive Peace Agreement benchmark, although they fell short • Doing business in Abou Shouk of international standards on the whole. The African Union Observer Mission said the • One block at a time elections, though imperfect, were historically significant and an important milestone • From guns to goods in the country’s peace and democratization process. Congratulating the Sudanese people, the League of Arab States Observer Mission hoped the elections would be a 9 Transport catalyst for further democratic transformation and development. Levelling Juba roads 18 April: UN Humanitarian Coordinator for Sudan Georg Charpentier warned that 10 Profile: Zeinab Badawi continued instability in parts of the eastern Jebel Marra area in Darfur had prevented agencies from accessing areas where they had been providing aid, including food, Knowing no fear water, and medicines, over the past five years. 11 Secretary-General’s report 26 April: Announcing preliminary results for Sudan’s elections, the National Ban calls for referenda preparations Elections Commission (NEC) declared that National Congress Party candidate Omar Al Bashir had topped the poll for President of Sudan with 68.2 per cent of the vote. -

Boating on the Nile

United Nations Mission September 2010 InSUDAN Boating on the Nile Published by UNMIS Public Information Office INSIDE 8 August: Meeting with Minister of Humanitarian Affairs Mutrif Siddiq, Joint Special Representative for Darfur 3 Special Focus: Transport Ibrahim Gambari expressed regrets on behalf of the • On every corner Diary African Union-UN Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) over • Boating on the Nile recent events in Kalma and Hamadiya internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in • Once a lifeline South Darfur and their possible negative impacts on the future of the peace process. • Keeping roads open • Filling southern skies 9 August: Blue Nile State members of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and National Congress Party (NCP) formed a six-member parliamentary committee charged with raising awareness about popular consultations on Comprehensive Peace Agreement 10 Photo gallery implementation in the state. The Sufi way 10 August: The SPLM and NCP began pre-referendum talks on wealth and power-sharing, 12 Profile demarcating the border, defining citizenship and sharing the Nile waters in preparation for the Knowledge as food southern self-determination vote, scheduled for 9 January 2011. 14 August: Two Jordanian police advisors with UNAMID were abducted in Nyala, Southern Darfur, 13 Environment as they were walking to a UNAMID transport dispatch point 100 meters from their residence. Reclaiming the trees Three days later the two police advisors were released unharmed in Kass, Southern Darfur. 14 Communications 16 August: Members of the Southern Sudan Human Rights Commission elected a nine-member The voice of Miraya steering committee to oversee its activities as the region approaches the self-determination referendum three days later the two police advisor were released unharmed in Kass, Southern Darfur. -

![IRNA Report: [Reggo and Tali Payam in Terekeka County, Centra Equotoria State]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0141/irna-report-reggo-and-tali-payam-in-terekeka-county-centra-equotoria-state-670141.webp)

IRNA Report: [Reggo and Tali Payam in Terekeka County, Centra Equotoria State]

IRNA Report: [Reggo and Tali payam in Terekeka County, Centra Equotoria State] [24-26th Amrch 2015] This IRNA Report is a product of Inter-Agency Assessment mission conducted and information compiled based on the inputs provided by partners on the ground including; government authorities, affected communities/IDPs and agencies. Situation overview Inter-agency Initial Rapid Needs Assessment (IRNA) was conducted from 24th to 26th March 2015, approximately 30days after the tribal conflict/clash between communities of Wujungani/Pariak village in Reggo payam and that of Lokweni/Bulukuli village of Terekeka payam. For Tali payam, the conflict started on 22/12/2015 and degenerated in late January and early Februeary 2015 between Mundari from Tali payam Terekeka in Central Equatoria and Dinka from Yirol County in Lake state. The IRNA conducted from 24-26th March 2015 in Terekeka County was represented by following cluster: Camp Coordination and Camp Management (CCCM), Food Security and Livelihoods (FSL), Health, Nutrition and WASH, Protection, Shelter and Non-Food Items (NFI)). The objective of this assessment was to assess the current situation of the conflict affected population in Reggo, Terekeka and Tali payam for appropriate decision making regarding protection and humanitarian assistance as might be required. The assessment team inter-phased with the local authority (i.e. Relief & Rehabilitation Commission (RRC), the Chiefs, and Herdsmen and the affected households of the affected areas in Reggo, TKK and Tali payam respectively. The local authorities were cooperative and appreciated the purpose of the mission. The main actors on the ground are ADRA for Health, NPA for FSL, ACORD for FSL and peace, SPEDC for FSL and education, AFOD for nutrition & CCCM, WIROCK for Education & Protection, etc As of RRC Terekeka Report dated 21st February, 2015 to the State Director RCRC copied to the Commissioner, the estimated affected population stands at 1562hh of 6,810 individuals in Wujungani, 684 hh of 3420 individuals in Pariak and 80 hh of 400 individuals in Lokweni. -

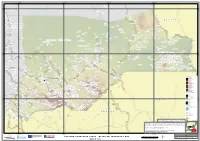

LC SS 706 A1 EEQ 20130301.Pdf

pp p ! ! p ! p (! ! !( 32°0'0"E 33°0'0"E 34°0'0"E 35°0'0"E Gwalla Awan KolnyangAluk Katanich Titong Munini Beru ! R . K Wowa ang en Logoda N Rigl Chilimun N " " 0 0 p' Bor South County ' 0 Pibor County Lowelli Katchikan River Bellel Kichepo 0 ° Maktiweng J O N G L E I ° 6 Kaigo 6 Lochiret R. Naro Kenamuke Swamp R Ngechele . S Neria u p Kanopir Natibok Kabalatigo i r i ( B Moru Kimod a Rongada h r Yebisak e g l- n Tombi J o e b b l Shogle e a l) Buka h C . Gwojo-Adung Kassangor R Baro ! E T H I O P I A Moru Kerri KURON Kuron Gigging p Bojo-Ajut Gemmaiza ! Karn Ethi Kerkeng Moru Ethi Nakadocwa Poko Wani Terekeka County Kobowen Swamp Borichadi Bokuna Poko Kassengo Selemani Pagar Nabwel Wani Mika Chabong Tukara C E N T R A L p River Nakua p Kenyi E Q U A T O R I A Moru Angbin Mukajo Gali Owiyabong Kursomba Lotimor Bulu Koli Kalaruz Awakot Katima Waha ! Akitukomoi River Gera Tumu Nanyangachor Nyabongi Napalap ! Namoropus Natilup Swamp ) it Wanyang Kangitabok Lomokori le Eyata Moru Kolinyagkopil il ! Terakeka ri Lozut Lomongole t iti o (! S L Magara p R. ( n Umm Gura Mwanyakapin a p y l Abuilingakine Lomareng Plateau a Dogora R Ngigalingatun k o . L Jelli L o p Rambo Djie Navi . Lokodopotok Nyaginei Kangeleng p R Biyara Nai A o Kworijik Kangibun Lomuleye Katirima t o Simsima Badigeru Swamp River Lokuja Losagam k Musha Lukwatuk Pass Doinyoro East p o p l Balala Legeri Buboli Kalopedet Pongo River Lokorowa Watha Peth Hills Bume E A S T E R N E Q U A T O R I A Lokidangoai Nawitapal Lopokori Lokomarukest Kolobeleng Yakara Dogatwan Nomogonjet Kagethi ! Mogos Bala Pool Lapon County Lotakawa Kanyabu Moru Ethi Donyiro West Donyiro Cliff Kedowa Kothokan a l l i Chokagiling t Karakamuge o Mangalla Bwoda L Mediket Kaliapus Nyangatom !( . -

Frontlines September/October 2011

FRONTLINES WWW.USAID.GOV SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2011 TWO SUDANS THE SEPARATION OF AFRICA’S LARGEST COUNTRY AND THE ROAD AHEAD > A GLOBAL EDUCATION FOOTPRINT TAKES SHAPE > EGYPT SHAKES UP THE CLASSROOM > Q&A WITH REP. NITA LOWEY Sudan & South Sudan/Education Edition INSIGHTS From Administrator Dr. Rajiv Shah A few weeks before South Sudan’s skills, making it more likely they will day of independence, I had the oppor- eventually drop out. tunity to visit the region and meet a These failures leave developing na- HE WORLD welcomed its group of children who were learning tions without the human and social newest nation when South English and math in a USAID-supported capital needed to advance and sustain Sudan officially gained its primary education program. The stu- development. They deprive too many inde pendence on July 9. After dents ranged in ages from 4 to 14. individuals of the skills they need as Tover two decades of war and suffering, Many of the older students have lived productive members of their commu- a peace agree ment between north and through a period of displacement, vio- nities and providers for their families. south Sudan paved the way for South lence, and trauma. This was likely the Across the world, our education pro- Sudanese to fulfill their dreams of self- very first opportunity they had to re- grams emphasize a special focus on determination. The United States played ceive even a basic education. disadvantaged groups such as women an important role in helping make this When you see American taxpayer and girls and those living in remote moment possible, and today we remain money being effectively used to provide areas.