Urban Displacement and Vulnerability in Yei, South Sudan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population Mobility Mapping (Pmm) South Sudan: Ebola Virus Disease (Evd) Preparedness

POPULATION MOBILITY MAPPING (PMM) SOUTH SUDAN: EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE (EVD) PREPAREDNESS CONTEXT The 10th EVD outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is still ongoing, with a total of 3,428 EVD cases reported as of 2 February 2020, including 3,305 confirmed and 118 probable cases. A total of 2,250 deaths have been reported, with a case fatality ratio (CFR) of 65.6%. Although the rate of new cases in DRC has decreased and stabilized, two health zones reported 25 new confirmed cases within the 21-day period from 13 January to 2 February 2019: Beni (n=18) and Mabalako (n=30).1 The EVD outbreak in DRC is the 2nd largest in history and is affecting the north-eastern provinces of the country, which border Uganda, Rwanda and South Sudan. South Sudan, labeled a 'priority 1' preparedness country, has continued to scale up preparedeness efforts since the outbreak was confirmed in Kasese district in South Western Uganda on 11 June 2019 and in Ariwara, DRC (70km from the South Sudan border) on 30 June 2019. South Sudan remains at risk while there is active transmission in DRC, due to cross-border population movements and a weak health system. To support South Sudan’s Ministry of Health and other partners in their planning for EVD preparedness, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) has applied its Population Mobility Mapping (PMM) approach to inform the prioritization of locations for preparedness activities. Aim and Objectives The aim of PMM in South Sudan is to inform the 2020 EVD National Preparedness Plan by providing partners with relevant information on population mobility and cross-border movements. -

Boating on the Nile

United Nations Mission September 2010 InSUDAN Boating on the Nile Published by UNMIS Public Information Office INSIDE 8 August: Meeting with Minister of Humanitarian Affairs Mutrif Siddiq, Joint Special Representative for Darfur 3 Special Focus: Transport Ibrahim Gambari expressed regrets on behalf of the • On every corner Diary African Union-UN Mission in Darfur (UNAMID) over • Boating on the Nile recent events in Kalma and Hamadiya internally displaced persons (IDP) camps in • Once a lifeline South Darfur and their possible negative impacts on the future of the peace process. • Keeping roads open • Filling southern skies 9 August: Blue Nile State members of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) and National Congress Party (NCP) formed a six-member parliamentary committee charged with raising awareness about popular consultations on Comprehensive Peace Agreement 10 Photo gallery implementation in the state. The Sufi way 10 August: The SPLM and NCP began pre-referendum talks on wealth and power-sharing, 12 Profile demarcating the border, defining citizenship and sharing the Nile waters in preparation for the Knowledge as food southern self-determination vote, scheduled for 9 January 2011. 14 August: Two Jordanian police advisors with UNAMID were abducted in Nyala, Southern Darfur, 13 Environment as they were walking to a UNAMID transport dispatch point 100 meters from their residence. Reclaiming the trees Three days later the two police advisors were released unharmed in Kass, Southern Darfur. 14 Communications 16 August: Members of the Southern Sudan Human Rights Commission elected a nine-member The voice of Miraya steering committee to oversee its activities as the region approaches the self-determination referendum three days later the two police advisor were released unharmed in Kass, Southern Darfur. -

Village Assessment Survey Morobo County

Village Assessment Survey COUNTY ATLAS 2013 Morobo County Central Equatoria State Village Assessment Survey The Village Assessment Survey (VAS) has been used by IOM since 2007 and is a comprehensive data source for South Sudan that provides detailed information on access to basic services, infra- structure and other key indicators essential to informing the development of efficient reintegra- tion programmes. The most recent VAS represents IOM’s largest effort to date encompassing 30 priority counties comprising of 871 bomas, 197 payams, 468 health facilities, and 1,277 primary schools. There was a particular emphasis on assessing payams outside state capitals, where com- paratively fewer comprehensive assessments have been carried out. IOM conducted the assess- ment in priority counties where an estimated 72% of the returnee population (based on esti- mates as of 2012) has resettled. The county atlas provides spatial data at the boma level and should be used in conjunction with the VAS county profile. Four (4) Counties Assessed Planning Map and Dashboard..…………Page 1 WASH Section…………..………...Page 14 - 20 General Section…………...……...Page 2 - 5 Natural Source of Water……...……….…..Page 14 Main Ethnicities and Languages.………...Page 2 Water Point and Physical Accessibility….…Page 15 Infrastructure and Services……...............Page 3 Water Management & Conflict....….………Page 16 Land Ownership and Settlement Type ….Page 4 WASH Education...….……………….…….Page 17 Returnee Land Allocation Status..……...Page 5 Latrine Type and Use...………....………….Page 18 Livelihood -

Tables from the 5Th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008

Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 CENSU OR S,S F TA RE T T IS N T E IC C S N A N A 123 D D β U E S V A N L R ∑σ µ U E A H T T I O U N O S S S C C S E Southern Sudan Counts: Tables from the 5th Sudan Population and Housing Census, 2008 November 19, 2010 ii Contents List of Tables ................................................................................................................. iv Acronyms ...................................................................................................................... x Foreword ....................................................................................................................... xiv Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................ xv Background and Mandate of the Southern Sudan Centre for Census, Statistics and Evaluation (SSCCSE) ...................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 History of Census-taking in Southern Sudan....................................................................... 2 Questionnaire Content, Sampling and Methodology ............................................................ 2 Implementation .............................................................................................................. 2 -

Mining in South Sudan: Opportunities and Risks for Local Communities

» REPORT JANUARY 2016 MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN: OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS FOR LOCAL COMMUNITIES BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF SMALL-SCALE AND ARTISANAL GOLD MINING IN CENTRAL AND EASTERN EQUATORIA STATES, SOUTH SUDAN MINING IN SOUTH SUDAN FOREWORD We are delighted to present you the findings of an assessment conducted between February and May 2015 in two states of South Sudan. With this report, based on dozens of interviews, focus group discussions and community meetings, a multi-disciplinary team of civil society and government representatives from South Sudan are for the first time shedding light on the country’s artisanal and small-scale mining sector. The picture that emerges is a remarkable one: artisanal gold mining in South Sudan ‘employs’ more than 60,000 people and might indirectly benefit almost half a million people. The vast majority of those involved in artisanal mining are poor rural families for whom alluvial gold mining provides critical income to supplement their subsistence livelihood of farming and cattle rearing. Ostensibly to boost income for the cash-strapped government, artisanal mining was formalized under the Mining Act and subsequent Mineral Regulations. However, owing to inadequate information-sharing and a lack of government mining sector staff at local level, artisanal miners and local communities are not aware of these rules. In reality there is almost no official monitoring of artisanal or even small-scale mining activities. Despite the significant positive impact on rural families’ income, the current form of artisanal mining does have negative impacts on health, the environment and social practices. With most artisanal, small-scale and exploration mining taking place in rural areas with abundant small arms and limited presence of government security forces, disputes over land access and ownership exacerbate existing conflicts. -

Central Equatorial / Morobo County, (Payams of Gulumbi and Kimba) Alert Date* (First Time the Location

Shelter Cluster South Sudan sheltersouthsudan.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter SHELTER/NFI ANALYSIS REPORT Field with (*) and italicized questions are mandatory. For checkboxes (☒), tick all that apply. Use charts from mobile data collection (MDC) wherever possible. 1. General Information Location* (State/County/Payam/Boma) Central Equatorial / Morobo County, (Payams of Gulumbi and Kimba) Alert Date* (first time the location mentioned to the Cluster) Analysis Dates* From 8th/11/2019 to 22nd /11/2019 2. Location Information Report Date* (date completed) GPS Coordinates* Kimba: Latitude N. 3°35’24.9’’ Longitude: E. 30° 48’26.8 Gulumbi : Latitude N. 3°40’ 43.2” Longitude: E. 30° 46’ 29.8” 3. Team Details* Name Organisation Title Contacts: Email/Mobile/Sat Phone Malish Lawrence SPEDP ES/NFI OFFICER (Team Leader) +211925460589, +211917049021 [email protected] Abiggo Manson Lubang SPEDP ES/NFI Officer [email protected] +211926088035/+256786387499 Aligo Daniel SPEDP Protection Officer [email protected] +25789435834 Apai Jackie SPEDP Protection Officer [email protected] +256779986856 If this is a joint mission, what %s will each partner report? [SPEDP 1]:100% [Partner 2]: ___% [Partner 3]: ___% SPEDPconducted the needs analysis 4. Desk Research: Displacement, Movement, and Conflict Trends What information did you find about the context and trends in this location more than six months ago? What triggered the analysis? Based on number of IRNA reports, UN OCHA report and independent need analysis done by SPEDP, and other agencies in Morobo County showed that with the signing of the revitalized Peace agreement, there is very high influx of returnees from Uganda and the democratic Republic of Congo into Morobo County right from Kaya the border which is in Kimba Payam and most of the Payams including Gulumbi Payam that has been covered in this household needs analysis report. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. 7 Background of the Landmine Impact Survey .......................................................................................... 16 Survey Results and Findings Scope of the Landmine Problem............................................................................................................. 21 Analysis of Economic Blockage Impacts................................................................................................. 41 Retrofit Results ....................................................................................................................................... 43 Past Mine Action .................................................................................................................................... 45 Profiles by State Blue Nile ................................................................................................................................................ 51 Central Equatoria................................................................................................................................... 57 Eastern Equatoria................................................................................................................................... 65 Gadaref.................................................................................................................................................. 71 Jonglei -

Operational Deployment Plan Template

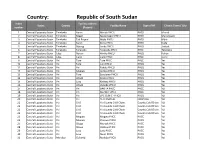

Country: Republic of South Sudan Index Facility Address States County Facility Name Type of HF Closest Town / City number (Payam) 1 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Nyori Moridi PHCU PHCU Moridi 2 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Reggo Makamagor PHCU PHCU Makamagor 3 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Tali Payam Mijiki PHCU PHCU Mijiki 4 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Nyori Kuda PHCU PHCU Kuda 5 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Rijiong Jonko PHCU PHCU Jonkok 6 Central Equatoria State Terekeka Terekeka Terekeka PHCC PHCC Terekeka 7 Central Equatoria State Juba Rokon Miriko PHCU PHCU Rokon 8 Central Equatoria State Juba Ganji Ganji PHCC PHCC Ganji 9 Central Equatoria State Yei Tore Tore PHCC PHCC Yei 10 Central Equatoria State Yei Tore Goli PHCU PHCU Yei 11 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei Pakula PHCU PHCU Yei 12 Central Equatoria State Yei Mugwo Jombu PHCU PHCU Yei 13 Central Equatoria State Yei Tore Bandame PHCU PHCU Yei 14 Central Equatoria State Yei Otogo Kejiko PHCU PHCU Yei 15 Central Equatoria State Yei Lasu Kirikwa PHCU PHCU Yei 16 Central Equatoria State Yei Otogo Rubeke PHCU PHCU Yei 17 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei BAKITA PHCC PHCC YEI 18 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei Marther PHCC PHCC YEI 19 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei EPC CLINIC - PHCU PHCU YEI 20 Central Equatoria State Yei Yei YEI HOSPITAL HOSPITAL YEI 21 Central Equatoria State Yei CHD Yei County Cold Chain County Cold Chain YEI 22 Central Equatoria State Yei CHD Yei County Cold Chain County Cold Chain YEI 23 Central Equatoria State Yei CHD Yei County Cold Chain County -

E4220v2 Republic of South Sudan Ministry of Agriculture & Forestry

E4220v2 Republic of South Sudan Ministry of Agriculture & Forestry Public Disclosure Authorized EMERGENCY FOOD CRISIS RESPONSE PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT REPORT May 2013 Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS III EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 4 1. BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROJECT AND THE STUDY 5 2. AN OVERVIEW OF THE AGRICULTURE SECTOR IN SOUTH SUDAN 14 3. REVIEW OF THE RELEVANT POLICIES, LAWS AND REGULATIONS 19 4. DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT ACTIVITIES AND IMPLEMENTATION APPROACH 26 6. PUBLIC CONSULTATIONS AND DISCLOSURE 48 7. PEST MANAGEMENT 52 8. ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL ISSUES, IMPACTS AND MITIGATION 55 9. ENVIRONMENT AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING PLAN 60 10. SUMMARY OF THE STUDY 66 11. REFERENCES 69 ii LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS AAHI Action Africa Help International CES Central Equatoria State CPA Comprehensive Peace Agreement EA Environmental Assessment EFCRP Emergency Food Crisis and Response Project ESA Environmental and Social Assessment ESAF Environment and Social Assessment Framework ESIA Environmental and Social Impact Assessment ESMF Environment and Social Management Framework ESMP Environment and Social Management Plan FAO Food and Agriculture Organization GDP Gross Domestic Product GFRP Global Food Crisis Response Program GNI Gross National Income GoSS Government of Southern Sudan IPM Integrated Pest Management IPMF Integrated Pest Management Framework IPMP Integrated Peoples Management -

Public Private Cooperation Fragile States

Public Private Cooperation Fragile States Annexe F to the Field study report South Sudan As part of the Country Study South Sudan Working group: Public Private Cooperation in Fragile States July 2009 1 Supplementary Document (annex F) to the Field Research Report on Public Private Cooperation opportunities in Southern Sudan, Nov 2009 by Irma Specht & Mark van Dorp (main researchers) and Washington Okeyo, Marjolein C. Groot and John Penn de Ngong 1. Specific (sub) sectors in more detail This annex provides, in more detail, the ongoing and potential sectors relevant for economic development and PPC in South Sudan. These are details found during the field research and are to complement the overview provided in the overall report. Oil and mineral production The most important economic activity in Southern Sudan is oil production, which is currently taking place in the oil rich regions of Upper Nile, Abyei and Unity State. Oil was discovered in Sudan in the mid-1970s, but production did not start until 1999. The pioneer companies Chevron and Shell were forced to leave in 1984, after the outbreak of civil war. They eventually sold their rights in 1990, booking a $1 billion loss. Major players that have controlled the oil industry in Sudan since the mid-nineties include the Chinese National Petroleum Company (CNPC) and Petronas Caligary from Malaysia, Lundin Petroleum from Sweden and ONGC Videsh from India. While, at a global level, Sudan is a minor oil exporting country, China, India and Malaysia have invested billions of dollars in the country, including outside the oil industry. They consider their relations with the country not only as economic, but also geostrategic and energy-strategic successes that are worth defending. -

South Sudan Country Operational Plan (COP)

FY 2015 South Sudan Country Operational Plan (COP) The following elements included in this document, in addition to “Budget and Target Reports” posted separately on www.PEPFAR.gov, reflect the approved FY 2015 COP for South Sudan. 1) FY 2015 COP Strategic Development Summary (SDS) narrative communicates the epidemiologic and country/regional context; methods used for programmatic design; findings of integrated data analysis; and strategic direction for the investments and programs. Note that PEPFAR summary targets discussed within the SDS were accurate as of COP approval and may have been adjusted as site- specific targets were finalized. See the “COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit” sheets that follow for final approved targets. 2) COP 15 Targets by Subnational Unit includes approved COP 15 targets (targets to be achieved by September 30, 2016). As noted, these may differ from targets embedded within the SDS narrative document and reflect final approved targets. Approved FY 2015 COP budgets by mechanism and program area, and summary targets are posted as a separate document on www.PEPFAR.gov in the “FY 2015 Country Operational Plan Budget and Target Report.” South Sudan Country/Regional Operational Plan (COP/ROP) 2015 Strategic Direction Summary August 27, 2015 Table of Contents Goal Statement 1.0 Epidemic, Response, and Program Context 1.1 Summary statistics, disease burden and epidemic profile 1.2 Investment profile 1.3 Sustainability Profile 1.4 Alignment of PEPFAR investments geographically to burden of disease 1.5 Stakeholder engagement -

July 2019 | Ebola Virus Disease Preparedness Report

IOM SOUTH SUDAN JULY 2019 | EBOLA VIRUS DISEASE PREPAREDNESS REPORT Lakes COUNTIES RECEIVING HYGIENE PROMOTION SUPPORT IOM DTM FLOW MONITORING POINT HEALTH FACILITIES SUPPORTED WITH IOM WASH INFRASTRUCTURE SOUTH Wau Airport SUDAN Dingimo CAR Source Yubu Nabia Pai Logobero DRC Lasu POINT OF ENTRY (PoE) SITE MANAGEMENT Lutaya Yei Taxi Park Jale Aweno Olwiyo Khor Kaya/ Kerwa IOM Bori WHO Elegu CUAMM Salia Musala WORLD VISION UGANDA FUTURE PoE SITES (TO BE MANAGED BY IOM) TOTAL SUSPECTED/ NON-EVD FEVER INDIVIDUALS REACHED NUMBER OF INDIVIDUALS CONFIRMED EVD CASES DETECTED & WITH HYGIENE HEALTH FACILITIES SCREENED: CASES: REFERRED: PROMOTION: SUPPORTED: 102,953 (In July 2019) 0 230 (In July 2019) 35,225 (In July 2019) 9 583,398 (Since Sept 2018) 1,251 (Since Sept 2018) 225,816 (Since Sept 2018) MONTHLY OVERVIEW HEALTH WASH ● A new PoE screening site was established and operationalized - Isebi PoE in ● The IOM team established a new PoE in Isebi, Lujulu county at the border of Lujulu Payam, Morobo County. Currently, IOM is operating 15 active PoE sites, South Sudan with DRC where a total of 17 volunteers were enlisted to conduct namely: Yei airstrip, Yei SSRRC, Tokori, Lasu, Kaya, Bazi, Salia Musala, Okaba, screening of in-bound travellers and to provide ebola virus disease (EVD) risk Khor Kaya (along Busia Uganda Border) and Isebi in Morobo County; Pure, communication to travelers and community around the PoE. Kerwa, Khorijo, Birigo in Lainya County; and Bori. ● The WASH team repaired Four previously non-functional boreholes located ● IOM supported and participated in the high-level delegation meeting in Yei Town, close to Isebi, Khor Kaya, Kerwa PoE sites and at Wudabi Primary Health Care during which the Yei Airstrip PoE screening site was visited by the delegation Centre to provide safe clean drinking water to travelers and community around members on 15 July 2019.