International Development Select Committee to Press HMG to Take the Following Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Sudan's Financial Sector

South Sudan’s Financial Sector Bank of South Sudan (BSS) Presentation Overview . Main messages & history/perspectives . Current state of the industry . Key issues – regulations, capitalization, skills, diversification, inclusion . The way forward “The road is under construction” Main Messages & History/perspectives . The history of financial institutions in South Sudan is a short one. Throughout Khartoum rule till the end of civil war in 2005, there were very few commercial banks concentrated in Juba, Wau and Malakal. South Sudanese were deliberately excluded from the economic system. As a result 90% of the population in South Sudan were not exposed to banking services . Access to finance was limited to Northern traders operating in Southern Sudan. In February 2008, Islamic banks left the South since the Bank of Southern Sudan(BOSS) introduced conventional banking . However, after the CPA the Bank of Southern Sudan, although a mere branch of the central bank of Sudan took a bold step by licensing local and expatriate banks that took interest to invest in South Sudan. South Sudan needs a stable, well diversified financial sector providing the right kinds of products and services with a level of intermediation and inclusion to support the country’s ambitions Current State of the Sector As of November 2013 . 28 Commercial Banks are now operating in South Sudan and more than 70 applications on the pipeline . 10 Micro Finance Institutions . 86 Forex Bureaus . A handful of Insurance companies Current state of the Sector (2) . Despite the increased number of financial institutions, competition is still limited and services are mainly concentrated in the urban hubs . -

The Greater Pibor Administrative Area

35 Real but Fragile: The Greater Pibor Administrative Area By Claudio Todisco Copyright Published in Switzerland by the Small Arms Survey © Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva 2015 First published in March 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission in writing of the Small Arms Survey, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organi- zation. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Publications Manager, Small Arms Survey, at the address below. Small Arms Survey Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies Maison de la Paix, Chemin Eugène-Rigot 2E, 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Series editor: Emile LeBrun Copy-edited by Alex Potter ([email protected]) Proofread by Donald Strachan ([email protected]) Cartography by Jillian Luff (www.mapgrafix.com) Typeset in Optima and Palatino by Rick Jones ([email protected]) Printed by nbmedia in Geneva, Switzerland ISBN 978-2-940548-09-5 2 Small Arms Survey HSBA Working Paper 35 Contents List of abbreviations and acronyms .................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Introduction and key findings .............................................................................................................................................. -

River Nile Politics: the Role of South Sudan

UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI INSTITUTE OF DIPLOMACY AND INTERNATIONAL STUDIES RIVER NILE POLITICS: THE ROLE OF SOUTH SUDAN R52/68513/2013 MATARA JAMES KAMAU A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE AWARD OF A DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN INTERNATIONAL CONFLICT MANAGEMENT. OCTOBER 2015 DECLARATION This research project is my original work and has not been submitted for another Degree in any other University Signature ……………………………..…Date……………………………………. Matara James Kamau, R52/68513/2013 This research project has been submitted for examination with my permission as the University supervisor Signature………………………………...Date…………………………………… Prof. Maria Nzomo ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost, all thanks to God Almighty for the strength and ability to pursue this degree. For without him, there would be no me. I wish to express my sincere thanks to Professor Maria Nzomo the research supervisor for her tireless effort and professional guidance in making this project a success. I also extend my deepest gratitude to entire university academic staff in particular those working in the Institute of Diplomacy and International Studies. iii DEDICATION I dedicate this research project to my entire Matara‘s family for moral and financial support during the time of research iv ABSTRACT This study focused on River Nile Politics, a study of the role of South Sudan. The study relates to the emergence of a new state amongst existing riparian states and how this may resonate with trans-boundary conflicts. The independence of South Sudan has been revealed in this study to have a mixture of unanswered questions. The study is grounded on Collier- Hoeffer theory analysed the trans-boundary conflict based on the framework of many variable including: identities, economics, religion and social status in the Nile basin. -

Global Witness ANNUAL REVIEW 2008 ABOUT GLOBAL WITNESS

ANNUAL REPORT 2008 global witness ANNUAL REVIEW 2008 ABOUT GLOBAL WITNESS THEY [GLOBAL WITNESS] EPITOMISE THE COMMITMENT, CREATIVITY AND DILIGENCE THAT SHOULD BE THE HALLMARK OF LEADERSHIP – WHETHER OF NON-PROFIT ADVOCACY GROUPS, COMPANIES, OR NATIONS…MOST NOTABLY [GLOBAL WITNESS] HAVE REJECTED EASY ANSWERS THAT, FOR TRUE CHAMPIONS OF PEACE, ARE FLEETING AND EMPTY. TONY P. HALL AND FRANK R. WOLF, MEMBERS OF US CONGRESS AND PATRICK LEAHY, US SENATOR RECOMMENDATION LETTER FOR THE 2003 NOBEL PEACE PRIZE GLOBAL WITNESS INVESTIGATES AND CAMPAIGNS Throughout 2008 Global Witness continued to make TO PREVENT NATURAL RESOURCE-RELATED CONFLICT great strides towards breaking the links between natural AND CORRUPTION AND ASSOCIATED ENVIRONMENTAL resource extraction and conflict, corruption and human AND HUMAN RIGHTS ABUSES. rights and environmental abuses across the world. From investigations into conflict minerals in the In 2006, aid flows to Africa totalled $49 billion while Democratic Republic of Congo and illegal logging in payments for natural resources were an incredible Liberia, to a new and ambitious strand of work on $250 billion. This discrepancy illustrates the potential banks and financial institutions, Global Witness that natural resources have to eliminate poverty continued to use its analysis, awareness-raising, and promote economic growth. The trade in natural lobbying, and policy development to advocate for resources is huge – and so are the profits associated systemic change. with it. However, often the benefits are diverted or co-opted by elites who ride roughshod over human By exposing the roots of conflict and corruption, and rights in their attempts at self-enrichment. Extensive refusing to accept that some problems are too large to corruption, particularly in vulnerable countries, including be tackled, or some attitudes too entrenched to be those that are coming out of lengthy periods of conflict, challenged, Global Witness seeks not just front-line exacerbates inequality and entrenches poverty. -

Preventing Odious Obligations

Center for Global Development Preventing Odious Obligations A New Tool for Protecting Citizens from Illegitimate Regimes A Report of the Working Group on the Prevention of Odious Debt Center for Development Global Preventing Odious Obligations A New Tool for Protecting Citizens from Illegitimate Regimes A Report of the Working Group on the Prevention of Odious Debt Copyright © 2010 by the Center for Global Development ISBN: 978-1-933286-56-3 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record has been requested Editing, design, and production by Christopher Trott and Elaine Wilson of Communications Development Incorporated, Washington, D.C., and Peter Grundy Art & Design, London. Working Group chairs Stephen D. Krasner, Stanford University; Formerly U.S. Seema Jayachandran, Assistant Professor of Economics, Department of State Stanford University Benjamin Leo, Center for Global Development, Formerly U.S. Michael Kremer, Non-Resident Fellow, Center for Global National Security Council and U.S. Treasury Development; Gates Professor of Developing Societies, Todd Moss, Center for Global Development; Formerly U.S. Department of Economics, Harvard University Department of State John Williamson, Visiting Fellow, Center for Global Richard Newcomb, DLA Piper Development; Senior Fellow, Peterson Institute for Yaga Venugopal Reddy, University of Hyderabad; Formerly International Economics Governor, Reserve Bank of India Nuhu Ribadu, Center for Global Development (on leave); Formerly Working Group members head of Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, Nigeria Nancy Birdsall, Center for Global Development Neil Watkins, ActionAid USA Lee Buchheit, Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP Ernesto Zedillo, Yale Center for the Study of Globalization; Joshua Cohen, Stanford University Formerly President of Mexico Paul Collier, Oxford University Economics Department Kimberly Elliott, Center for Global Development Staff Jesus P. -

The Heart of the Matter

THE HEART OF THE MATTER SIERRA LEONE, DIAMONDS & HUMAN SECURITY (COMPLETE REPORT) Ian Smillie Lansana Gberie Ralph Hazleton Partnership Africa Canada (PAC) is a coalition of Canadian and African organizations that work in partnership to promote sustainable human development policies that benefit African and Canadian societies. The Insights series seeks to deepen understanding of current issues affecting African development. The series is edited by Bernard Taylor. The Heart of the Matter: Sierra Leone, Diamonds and Human Security (Complete Report) Ian Smillie, Lansana Gberie, Ralph Hazleton ISBN 0-9686270-4-8 © Partnership Africa Canada, January 2000 Partnership Africa Canada 323 Chapel St., Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1N 7Z2 [email protected] P.O. Box 60233, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia pac@ telecom.net.et ________________ The Authors Ian Smillie, an Ottawa-based consultant, has 30 years of international development experience, as manager, programmer, evaluator and writer. He was a founder of the Canadian NGO Inter Pares, and was Executive Director of CUSO from 1979 to 1983. His most recent publications include The Alms Bazaar: Altruism Under Fire; Non Profit Organizations and International Development (IT Publications, London, 1995) and Stakeholders: Government-NGO Partnerships for International Development (ed. With Henny Helmich, Earthscan, London, 1999). Since 1997 he has worked as an associate with the Thomas J. Watson Jr. Institute at Brown University on issues relating to humanitarianism and war. Ian Smillie started his international work in 1967 as a teacher in Koidu, the centre of Sierra Leone’s diamond mining area. Lansana Gberie is a doctoral student at the University of Toronto and research associate at the Laurier Centre for Military, Strategic and Disarmament Studies, Waterloo, Ontario. -

Peace Is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp By

SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES pROjECT PEACE IS THE NAME OF OUR CATTLE-CAMP LOCAL RESPONSES TO CONFLICT IN EASTERN LAKES STATE, SOUTH SUDAN SOUTH SUDAN CUSTOMARY AUTHORITIES PROJECT Peace is the Name of Our Cattle-Camp Local responses to conflict in Eastern Lakes State, South Sudan JOHN RYLE AND MACHOT AMUOM Authors John Ryle (co-author), Legrand Ramsey Professor of Anthropology at Bard College, New York, was born and educated in the United Kingdom. He is lead researcher on the RVI South Sudan Customary Authorities Project. Machot Amuom Malou (co-author) grew up in Yirol during Sudan’s second civil war. He is a graduate of St. Lawrence University, Uganda, and a member of The Greater Yirol Youth Union that organised the 2010 Yirol Peace Conference. Abraham Mou Magok (research consultant) is a graduate of the Nile Institute of Management Studies in Uganda. Born in Aluakluak, he has worked in local government and the NGO sector in Greater Yirol. Aya piŋ ëë kͻcc ἅ luël toc ku wεl Ɣͻk Ɣͻk kuek jieŋ ku Atuot akec kaŋ thör wal yic Yeŋu ye köc röt nͻk wεt toc ku wal Mith thii nhiar tͻͻŋ ku ran wut pεεc Yin aci pεεc tik riεl Acin ke cam riεlic Kͻcdit nyiar tͻͻŋ Ku cͻk ran nͻk aci yͻk thin Acin ke cam riεlic Wut jiëŋ ci riͻc Wut Atuot ci riͻc Yok Ɣen Apaak ci riͻc Yen ya wutdie Acin kee cam riεlic ëëë I hear people are fighting over grazing land. Cattle don’t fight—neither Jieŋ cattle nor Atuot cattle. Why do we fight in the name of grass? Young men who raid cattle-camps— You won’t get a wife that way. -

Diamonds, the Kimberley Process, and Civil War in Sub-Saharan Africa

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-1-2015 Diamonds, the Kimberley Process, and Civil War in Sub-Saharan Africa Haley Anne Mccormick University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the African Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Repository Citation Mccormick, Haley Anne, "Diamonds, the Kimberley Process, and Civil War in Sub-Saharan Africa" (2015). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2383. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/7645959 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DIAMONDS, THE KIMBERLEY PROCESS, AND CIVIL WAR IN SUB-SAHRAN AFRICA By Haley McCormick Bachelor of Arts in Political Science Brigham Young University 2011 A thesis submitted in partial -

Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations

Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Committee on Foreign Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives Hearing entitled “Is There an African Resource Curse?” July 18, 2013 Testimony of Corinna Gilfillan, Director of U.S. Office, Global Witness Good afternoon Chairman Smith, Ranking Member Bass and members of the Subcommittee. Thank you very much for holding this hearing today to focus on the important issue of tackling the resource curse in Africa. My name is Corinna Gilfillan, Director of Global Witness’s Washington, DC office which is an international advocacy organization headquartered in London that investigates and campaigns to break the links between natural resources, corruption and conflict. Global Witness has carried out pioneering work for nearly 20 years to expose natural resource- related conflict and corruption and associated environmental and human rights abuses and much of this work has focused on Africa. One of our early campaigns exposed how diamonds financed brutal conflicts in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Angola, which brought the problem of blood diamonds to international attention. Our investigations in Africa and globally have revealed how timber, diamonds, minerals, oil and other natural resources incentivize corruption, destabilize governments and fuel conflicts, rather than benefiting a country’s citizens. Through our investigations, research and high-level advocacy we advocate for solutions to the resource curse so that citizens of resource-rich countries can get a fair share of their country’s wealth. Many countries in Africa and globally that are rich in oil, gas and other minerals are mired in poverty because the public revenues earned from selling these resources are being squandered through corruption and lack of government accountability. -

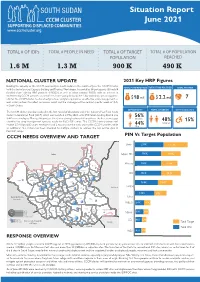

June 2021 Situation Report

SOUTH SUDAN Situation Report June 2021 TOTAL # OF IDPs TOTAL # PEOPLE IN NEED TOTAL # OF TARGET TOTAL # OF POPULATION POPULATION REACHED 1.6 M 1.3 M 900 K 490 K NATIONAL CLUSTER UPDATE 2021 Key HRP Figures Building the capacity of the CCCM community in South Sudan, in the month of June the CCCM Cluster TOTAL FUND REQUIRED TOTAL FUND RECEIVED TOTAL PARTNER held the rst of several Capacity Building and Training Workshops. Attended by 38 participants (30 male/8 females) from existing HRP partners (I/NGOs) as well as other national NGOs with an interest in implementing CCCM activities as part of the cluster going forward, the 2 day workshop was an opportu- nity for the CCCM cluster to share best practices and global guidelines on eective camp management, as 18 mil 2.2 mil 7 well as for partners to reect on lessons learnt and the challenges of the context specic needs of IDPs in South Sudan. DEMOGRAPHY TOTAL CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES The CCCM cluster was also involved in the rst round of allocations under the Country Pool Fund South Sudan Humanitarian Fund (SSHF) which was launched in May 2021, with $50 million funding divided into 56% 3 dierent envelopes. During this process, the cluster strongly advocated to address the key service gaps Women identied by camp management agencies inside the PoC/ IDP camps. The CCCM cluster partners will 48% 15% Children receive 2.5 million USD under envelope 1 and 2, to carry out the static and mobile CCCM activities, while 44% Men an additional 16.5 million has been allocated to multiple clusters to address the key service gaps in PoC/IDP camps. -

Global Witness Annual Review 2014 20 Years of Impact

GLOBAL WITNESS ANNUAL REVIEW 2014 20 YEARS OF IMPACT In essence, Global Witness created the movement, since joined by a number of other organizations, 20 YEARS to disclose publicly the vast sums involved in the CONTENTS extraction of natural resources and the frequent OF IMPACT misuse of those funds …its impact in the human rights field in demonstrating how the Khmer Rouge financed itself, or in exposing the role of the Liberian dictator Charles Taylor in the ghastly conflict in Sierra Leone, has been substantial. _ Aryeh Neier, former President, Open Society Foundations 1995-97 Global Witness shows that illegal timber 2009 Publication of Undue Diligence, a landmark 04 FOUNDER’s 16 NATURAL RESOURCES trading between Cambodia and Thailand, with complicity two-year investigation into the role of the banking MESSAGE & ArMED CONFLICT at the highest official levels, is funding the genocidal and finance sector in facilitating corruption. Stopping supply chains fuelling conflict Khmer Rouge. As a result, the border is closed, depriving New U.S. laws on Congo’s conflict minerals Khmer Rouge of at least $90 million a year. 2010 Global Witness plays key role in informing legislative process leading to new U.S. law on supply chains in conflict-prone 06 FORESTS Influencing regulations in DRC, EU and China 1998 Investigations into the diamond trade in Angola environments (section 1502 of Dodd Frank Act) which requires & LAND Keeping the spotlight on blood diamonds and West Africa alert the world to blood diamonds, U.S. companies sourcing minerals from Democratic Republic Exposing Europe’s timber Demanding transparency in South Sudan leading to the creation of the Kimberley Process. -

BREAKING the LINKS BETWEEN NATURAL RESOURCES, CONFLICT and CORRUPTION Annual Report 2006

BREAKING THE LINKS BETWEEN NATURAL RESOURCES, CONFLICT AND CORRUPTION Annual Report 2006 © xxxxxxxx Pipelines carry natural gas from Turkmenistan through Russia and Ukraine to Europe, providing a vital supply of European energy – but where does the money go? Pipe system, Western Ukraine © K.Thomas / Still Pictures www.globalwitness.org Front cover image: Diamond mining in Sierra Leone © Fredrik Naumann / Panos Pictures Highlights of 2006 Read more on page • Launching an international advocacy campaign highlighting the need for a coherent defi nition of 7 confl ict resources. This is part of an overarching Global Witness initiative to promote an international framework which will better control natural resources and the fl ows of confl ict fi nance. • Raising public awareness of the ongoing problem of confl ict diamonds and the wider global problem of confl ict resources - maximising opportunities created by the release of Hollywood blockbuster 8 Blood Diamond and successfully campaigning for crucial improvements in the Kimberley Process including the need for increased government oversight of the diamond industry. • Highlighting how British company Afrimex contributed to the devastating confl ict in the Democratic 10 Republic of Congo by trading in confl ict resources, including testifying before the UK Parliamentary International Development Committee. • Supporting, with hard facts and analysis, Liberian President Sirleaf’s call for the renegotiation of a 12 grossly inequitable US$900 million mining deal between Mittal Steel, the world’s biggest steel company, and the Government of Liberia and helping to ensure a better deal for the people of Liberia. • Our investigations contributing to Dutch arms dealer and timber trader Gus Kouwenhoven being 14 sentenced to eight years in prison for breaking a UN arms embargo, and as such helping to fuel confl ict in West Africa.