Iv INDONESIA Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Surrealist Painting in Yogyakarta Martinus Dwi Marianto University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1995 Surrealist painting in Yogyakarta Martinus Dwi Marianto University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Marianto, Martinus Dwi, Surrealist painting in Yogyakarta, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 1995. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/1757 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] SURREALIST PAINTING IN YOGYAKARTA A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by MARTINUS DWI MARIANTO B.F.A (STSRI 'ASRT, Yogyakarta) M.F.A. (Rhode Island School of Design, USA) FACULTY OF CREATIVE ARTS 1995 CERTIFICATION I certify that this work has not been submitted for a degree to any other university or institution and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference has been made in the text. Martinus Dwi Marianto July 1995 ABSTRACT Surrealist painting flourished in Yogyakarta around the middle of the 1980s to early 1990s. It became popular amongst art students in Yogyakarta, and formed a significant style of painting which generally is characterised by the use of casual juxtapositions of disparate ideas and subjects resulting in absurd, startling, and sometimes disturbing images. In this thesis, Yogyakartan Surrealism is seen as the expression in painting of various social, cultural, and economic developments taking place rapidly and simultaneously in Yogyakarta's urban landscape. -

Empires in East Asia

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=NL-C Module 3 Empires in East Asia Essential Question In general, was China helpful or harmful to the development of neighboring empires and kingdoms? About the Photo: Angkor Wat was built in In this module you will learn how the cultures of East Asia influenced one the 1100s in the Khmer Empire, in what is another, as belief systems and ideas spread through both peaceful and now Cambodia. This enormous temple was violent means. dedicated to the Hindu god Vishnu. What You Will Learn … Explore ONLINE! Lesson 1: Tang and Song China . 80 The Big Idea During the Tang and Song dynasties, China experienced VIDEOS, including... an era of prosperity and technological innovation. • A Mongol Empire in China Lesson 2: The Mongols . 90 • Ancient Discoveries: Chinese Warfare The Big Idea The Mongols, a nomadic people from the steppe, • Ancient China: Masters of the Wind conquered settled societies across much of Asia and established the and Waves Yuan Dynasty to rule China. • Marco Polo: Journey to the East Lesson 3: Korean Dynasties . 100 The Big Idea The Koreans adapted Chinese culture to fi t their own • Rise of the Samurai Class needs but maintained a distinct way of life. • How the Vietnamese Defeated Lesson 4: Feudal Powers in Japan. 104 the Mongols The Big Idea Japanese civilization was shaped by cultural borrowing • Lost Spirits of Cambodia from China and the rise of feudalism and military rulers. Lesson 5: Kingdoms of Southeast Asia . 110 The Big Idea Several smaller kingdoms prospered in Southeast Asia, Document-Based Investigations a region culturally infl uenced by China and India. -

The Professionalisation of the Indonesian Military

The Professionalisation of the Indonesian Military Robertus Anugerah Purwoko Putro A thesis submitted to the University of New South Wales In fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences July 2012 STATEMENTS Originality Statement I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged. Copyright Statement I hereby grant to the University of New South Wales or its agents the right to archive and to make available my thesis or dissertation in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I retain all property rights, such as patent rights. I also retain the right to use in future works (such as articles or books) all or part of this thesis or dissertation. Authenticity Statement I certify that the Library deposit digital copy is a direct equivalent of the final officially approved version of my thesis. -

The West Papua Dilemma Leslie B

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2010 The West Papua dilemma Leslie B. Rollings University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Rollings, Leslie B., The West Papua dilemma, Master of Arts thesis, University of Wollongong. School of History and Politics, University of Wollongong, 2010. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3276 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. School of History and Politics University of Wollongong THE WEST PAPUA DILEMMA Leslie B. Rollings This Thesis is presented for Degree of Master of Arts - Research University of Wollongong December 2010 For Adam who provided the inspiration. TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION................................................................................................................................ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. ii ABSTRACT ...................................................................................................................................... iii Figure 1. Map of West Papua......................................................................................................v SUMMARY OF ACRONYMS ....................................................................................................... vi INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................................................1 -

Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia

Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia As the largest Muslim country in the world, Indonesia is marked by an extraordinary diversity of languages, traditions, cultures, and religions. Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia focuses on Dani Christians of West Papua, providing a social and ethnographic history of the most important indigenous population in the troubled province. It presents a captivating overview of the Dani conversion to Christianity, examining the social, religious, and political uses to which they have put their new religion. Farhadian provides the first major study of a highland Papuan group in an urban context, which distinguishes it from the typical highland Melanesian ethnography. Incorporating cultural and structural approaches, the book affords a fascinating look into the complex relationship among Christianity, Islam, nation making, and indigenous traditions. Based on research over many years, Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia offers an abundance of new material on religious and political events in West Papua. The book underlines the heart of Christian–Muslim rivalries, illuminating the fate of religion in late-modern times. Charles E. Farhadian is Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at Westmont College, Santa Barbara, California. Routledge Contemporary Southeast Asia Series 1 Land Tenure, Conservation and Development in Southeast Asia Peter Eaton 2 The Politics of Indonesia–Malaysia Relations One kin, two nations Joseph Chinyong Liow 3 Governance and Civil Society in Myanmar Education, health and environment Helen James 4 Regionalism in Post-Suharto Indonesia Edited by Maribeth Erb, Priyambudi Sulistiyanto, and Carole Faucher 5 Living with Transition in Laos Market integration in Southeast Asia Jonathan Rigg 6 Christianity, Islam, and Nationalism in Indonesia Charles E. -

The Conflict in the Moluccas

Peace and Conflict Studies III Spring Semester 2013 Supervisor: Kristian Steiner Faculty of Culture and Society Department of Global Political Studies The Conflict in the Moluccas: Local Youths’ Perceptions Contrasted to Previous Research Martin Björkhagen Words: 16 434 Abstract The violent conflict in the Moluccas (1999-2002) has occasionally been portrayed in terms of animosities between Christians and Muslims. This study problematizes that statement by analysing several conflict drivers seen through two perspectives. The first purpose of this study was to contrast previous research regarding conflict factors in the Moluccas to the perceptions of the local youths’. There is a research gap regarding the youths’ experiences of the conflict, which this study aims to bridge. A second purpose was to analyse discrepancy between the academic literature and the youths’ bottom-up perspective. The final purpose was to apply the theory of collective guilt to explain and analyse the youths’ memories and perceptions regarding the conflict factors in the Moluccas. The qualitative case study approach was adopted since it could include both in-depth interviews and an assessed literature review. Six in-depth interviews were conducted in Indonesia which explored the youth’s perceptions. The critically assessed literature review was used to obtain data from secondary sources regarding the same conflict factors, as was explored by the interviews. The first part of the analysis exposed a discrepancy between the two perspectives regarding some of the conflict factors. The collective guilt analysis found that the youths only seem to experience a rather limited feeling of collective guilt. This is because all strategies to reduce collective guilt were represented in the youths’ perceptions. -

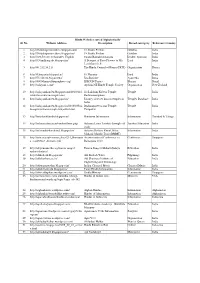

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

The Development of Kaji Kito in Nichiren Shu Buddhism Kyomi J

The Development of Kaji Kito in Nichiren Shu Buddhism Kyomi J. Igarashi Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Prerequisite for Honors in Religion April 2012 Copyright 2012 Kyomi J. Igarashi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Kodera for his guidance and all that he has taught me throughout my four years at Wellesley College. I could not have written this thesis or taken on this topic of my interest without his encouragement and words of advice. I would like to acknowledge the Religion Department for funding me on my trip to Japan in December 2011 to do research for my thesis. I would also like to thank Reverend Ekyo Tsuchida for his great assistance and dedication during my trip to Japan in finding important information and setting up interviews for me, without which I could not have written this thesis. I am forever grateful for your kindness. I express my gratitude to Reverend Ryotoku Miyagawa, Professor Akira Masaki and Professor Daijo Takamori for kindly offering their expertise and advice as well as relevant sources used in this thesis. I would also like to acknowledge Reverend Honyo Okuno for providing me with important sources as well as giving me the opportunity to observe the special treasures exhibited at the Kuonji Temple in Mount. Minobu. Last but not least, I would like to extend my appreciation to my father, mother and younger brother who have always supported me in all my decisions and endeavors. Thank you for the support that you have given me. ii ABSTRACT While the historical and religious roots of kaji kito (“ritual prayer”) lay in Indian and Chinese Esoteric Buddhist practices, the most direct influence of kaji kito in Nichiren Shu Buddhism, a Japanese Buddhist sect founded by the Buddhist monk, Nichiren (1222-1282), comes from Shingon and Tendai Buddhism, two traditions that precede Nichiren’s time. -

The Gods & the Forge

ificah International Foundation of Indonesian Culture and Asian Heritage The Gods & the Forge Balinese Ceremonial Blades The Gods & the Forge in a Cultural Context This publication is the companion volume for the exhibition of the same name at the IFICAH Museum of Asian Culture in Hollenstedt-Wohlesbostel, Germany December 2015 to October 2016. Title number IFICAH V01E © IFICAH, International Foundation of Indonesian Culture and Asian Heritage Text: Dr. Achim Weihrauch, Efringen-Kirchen, Germany Dr. Udo Kloubert, Erkrath, Germany Adni Aljunied, Singapore Photography: Günther Heckmann, Hollenstedt, Germany Printing: Digital Repro Druck GmbH, Ostfildern, Germany Layout: S&K Kommunikation, Osnabrück, Germany Editing: Kerstin Thierschmidt, Düsseldorf, Germany Image editing: Concept 33, Ostfildern, Germany Exhibition design: IFICAH Display cases: Glaserei Ahlgrim, Zeven, Germany "Tradition is not holding onto the ashes, Metallbau Stamer, Grauen, Germany Conservation care: but the passing on of the flame." Daniela Heckmann, Hollenstedt, Germany Thomas Moore (1477–1535) Translation: Comlogos, Fellbach, Germany 04 05 Foreword Summer 2015. Ketut, a native of Bali, picks me Years earlier, the fishermen had sold the land up on an ancient motorcycle. With our feet bordering the beach to Western estate agents, clad in nothing more resilient than sandals, we which meant however that they can now no ride along streets barely worthy of the name longer access the sea with their boats ... to the hinterland. We meet people from dif- ferent generations who live in impoverished It is precisely these experiences that underline conditions by western standards and who wel- the urgency of the work carried out by IFICAH – come the "giants from the West" with typi- International Foundation of Indonesian Culture cal Balinese warmth. -

From Ethnocide to Ethnodevelopment? Ethnic Minorities and Indigenous Peoples in Southeast Asia

Third World Quarterly, Vol 22, No 3, pp 413–4 36, 2001 From ethnocide to ethnodevelopment? Ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples in Southeast Asia GERARD CLARKE ABSTRACT This paper examines the impact of development, including the impact of government and donor programmes, on ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples in Southeast Asia. Through an examination of government policy, it considers arguments that mainstream development strategies tend to generate conflicts between states and ethnic minorities and that such strategies are, at times, ethnocidal in their destructive effects on the latter. In looking at more recent government policy in the region, it considers the concept of ethno- development (ie development policies that are sensitive to the needs of ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples and where possible controlled by them), and assesses the extent to which such a pattern of development is emerging in the region. Since the late 1980s, it argues, governments across the region have made greater efforts to acknowledge the distinct identities of both ethnic minorities and indigenous peoples, while donors have begun to fund projects to address their needs. In many cases, these initiatives have brought tangible benefits to the groups concerned. Yet in other respects progress to date has been modest and ethnodevelopment, the paper argues, remains confined to a limited number of initiatives in the context of a broader pattern of disadvantage and domination. Ama Puk is a prosperous coffee farmer in Vietnam’s Dak Lak province. A member of the Ede (E De) minority, Ama lived in perennial poverty as a subsis- tence rice producer until the establishment of the state-run Ea Tul Coffee Company in 1985. -

Women Under Sharia: Case Studies in the Implementation of Sharia-Influenced Regional Regulations (Perda Sharia) in Indonesia

Women Under Sharia: Case Studies in the Implementation of Sharia-Influenced Regional Regulations (Perda Sharia) in Indonesia Erwin Nur Rif’ah, M.A. A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy College of Arts Victoria University Australia December, 2014 Declaration of Originality I certify that this thesis does not incorporate without acknowledgement any material previously submitted for a degree or diploma in any university; and that to the best of my knowledge and belief it does not contain any material previously published or written by another person except where due reference is made in the text. Signed: On: 19/12/2014 ii Abstract Women Under Sharia: Case Studies in the Implementation of Sharia-Influenced Regional Regulations (Perda Sharia) in Indonesia This study examines the religious, social and political dynamics of Perda Sharia and how the implementation of these regulations has affected women rights and women’s security. This study also explores the concept of women’s security based on women’s own experiences. It employed qualitative methodologies, including in-depth interviews, focus group discussions and analysis of primary source documentation. It examined Perda Sharia in two district governments: Cianjur, West Java and Bulukumba, South Sulawesi. My research argues that Perda Sharia was the outcome of the local political processes reflecting the interaction of regional autonomy, democratisation and the Islamic resurgence. Given the struggle for Sharia since Indonesian independence, the widespread implementation of Perda Sharia suggests that it has been widely accepted as part of the legal system in district governments. This research found that the implementation of Perda Sharia has strengthened the position of Islam as a social and cultural force, but not necessarily of Islam’s influence in politics or government and as such it is a great accomplishment for its supporters. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore