Chapter 6 – Multiphase Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thermodynamics

TREATISE ON THERMODYNAMICS BY DR. MAX PLANCK PROFESSOR OF THEORETICAL PHYSICS IN THE UNIVERSITY OF BERLIN TRANSLATED WITH THE AUTHOR'S SANCTION BY ALEXANDER OGG, M.A., B.Sc., PH.D., F.INST.P. PROFESSOR OF PHYSICS, UNIVERSITY OF CAPETOWN, SOUTH AFRICA THIRD EDITION TRANSLATED FROM THE SEVENTH GERMAN EDITION DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC. FROM THE PREFACE TO THE FIRST EDITION. THE oft-repeated requests either to publish my collected papers on Thermodynamics, or to work them up into a comprehensive treatise, first suggested the writing of this book. Although the first plan would have been the simpler, especially as I found no occasion to make any important changes in the line of thought of my original papers, yet I decided to rewrite the whole subject-matter, with the inten- tion of giving at greater length, and with more detail, certain general considerations and demonstrations too concisely expressed in these papers. My chief reason, however, was that an opportunity was thus offered of presenting the entire field of Thermodynamics from a uniform point of view. This, to be sure, deprives the work of the character of an original contribution to science, and stamps it rather as an introductory text-book on Thermodynamics for students who have taken elementary courses in Physics and Chemistry, and are familiar with the elements of the Differential and Integral Calculus. The numerical values in the examples, which have been worked as applications of the theory, have, almost all of them, been taken from the original papers; only a few, that have been determined by frequent measurement, have been " taken from the tables in Kohlrausch's Leitfaden der prak- tischen Physik." It should be emphasized, however, that the numbers used, notwithstanding the care taken, have not vii x PREFACE. -

Solutes and Solution

Solutes and Solution The first rule of solubility is “likes dissolve likes” Polar or ionic substances are soluble in polar solvents Non-polar substances are soluble in non- polar solvents Solutes and Solution There must be a reason why a substance is soluble in a solvent: either the solution process lowers the overall enthalpy of the system (Hrxn < 0) Or the solution process increases the overall entropy of the system (Srxn > 0) Entropy is a measure of the amount of disorder in a system—entropy must increase for any spontaneous change 1 Solutes and Solution The forces that drive the dissolution of a solute usually involve both enthalpy and entropy terms Hsoln < 0 for most species The creation of a solution takes a more ordered system (solid phase or pure liquid phase) and makes more disordered system (solute molecules are more randomly distributed throughout the solution) Saturation and Equilibrium If we have enough solute available, a solution can become saturated—the point when no more solute may be accepted into the solvent Saturation indicates an equilibrium between the pure solute and solvent and the solution solute + solvent solution KC 2 Saturation and Equilibrium solute + solvent solution KC The magnitude of KC indicates how soluble a solute is in that particular solvent If KC is large, the solute is very soluble If KC is small, the solute is only slightly soluble Saturation and Equilibrium Examples: + - NaCl(s) + H2O(l) Na (aq) + Cl (aq) KC = 37.3 A saturated solution of NaCl has a [Na+] = 6.11 M and [Cl-] = -

Equation of State for Benzene for Temperatures from the Melting Line up to 725 K with Pressures up to 500 Mpa†

High Temperatures-High Pressures, Vol. 41, pp. 81–97 ©2012 Old City Publishing, Inc. Reprints available directly from the publisher Published by license under the OCP Science imprint, Photocopying permitted by license only a member of the Old City Publishing Group Equation of state for benzene for temperatures from the melting line up to 725 K with pressures up to 500 MPa† MONIKA THOL ,1,2,* ERIC W. Lemm ON 2 AND ROLAND SPAN 1 1Thermodynamics, Ruhr-University Bochum, Universitaetsstrasse 150, 44801 Bochum, Germany 2National Institute of Standards and Technology, 325 Broadway, Boulder, Colorado 80305, USA Received: December 23, 2010. Accepted: April 17, 2011. An equation of state (EOS) is presented for the thermodynamic properties of benzene that is valid from the triple point temperature (278.674 K) to 725 K with pressures up to 500 MPa. The equation is expressed in terms of the Helmholtz energy as a function of temperature and density. This for- mulation can be used for the calculation of all thermodynamic properties. Comparisons to experimental data are given to establish the accuracy of the EOS. The approximate uncertainties (k = 2) of properties calculated with the new equation are 0.1% below T = 350 K and 0.2% above T = 350 K for vapor pressure and liquid density, 1% for saturated vapor density, 0.1% for density up to T = 350 K and p = 100 MPa, 0.1 – 0.5% in density above T = 350 K, 1% for the isobaric and saturated heat capaci- ties, and 0.5% in speed of sound. Deviations in the critical region are higher for all properties except vapor pressure. -

Determination of the Identity of an Unknown Liquid Group # My Name the Date My Period Partner #1 Name Partner #2 Name

Determination of the Identity of an unknown liquid Group # My Name The date My period Partner #1 name Partner #2 name Purpose: The purpose of this lab is to determine the identity of an unknown liquid by measuring its density, melting point, boiling point, and solubility in both water and alcohol, and then comparing the results to the values for known substances. Procedure: 1) Density determination Obtain a 10mL sample of the unknown liquid using a graduated cylinder Determine the mass of the 10mL sample Save the sample for further use 2) Melting point determination Set up an ice bath using a 600mL beaker Obtain a ~5mL sample of the unknown liquid in a clean dry test tube Place a thermometer in the test tube with the sample Place the test tube in the ice water bath Watch for signs of crystallization, noting the temperature of the sample when it occurs Save the sample for further use 3) Boiling point determination Set up a hot water bath using a 250mL beaker Begin heating the water in the beaker Obtain a ~10mL sample of the unknown in a clean, dry test tube Add a boiling stone to the test tube with the unknown Open the computer interface software, using a graph and digit display Place the temperature sensor in the test tube so it is in the unknown liquid Record the temperature of the sample in the test tube using the computer interface Watch for signs of boiling, noting the temperature of the unknown Dispose of the sample in the assigned waste container 4) Solubility determination Obtain two small (~1mL) samples of the unknown in two small test tubes Add an equal amount of deionized into one of the samples Add an equal amount of ethanol into the other Mix both samples thoroughly Compare the samples for solubility Dispose of the samples in the assigned waste container Observations: The unknown is a clear, colorless liquid. -

Page 1 of 6 This Is Henry's Law. It Says That at Equilibrium the Ratio of Dissolved NH3 to the Partial Pressure of NH3 Gas In

CHMY 361 HANDOUT#6 October 28, 2012 HOMEWORK #4 Key Was due Friday, Oct. 26 1. Using only data from Table A5, what is the boiling point of water deep in a mine that is so far below sea level that the atmospheric pressure is 1.17 atm? 0 ΔH vap = +44.02 kJ/mol H20(l) --> H2O(g) Q= PH2O /XH2O = K, at ⎛ P2 ⎞ ⎛ K 2 ⎞ ΔH vap ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = ln⎜ ⎟ − ⎜ − ⎟ equilibrium, i.e., the Vapor Pressure ⎝ P1 ⎠ ⎝ K1 ⎠ R ⎝ T2 T1 ⎠ for the pure liquid. ⎛1.17 ⎞ 44,020 ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = − ⎜ − ⎟ = 1 8.3145 ⎜ T 373 ⎟ ⎝ ⎠ ⎝ 2 ⎠ ⎡1.17⎤ − 8.3145ln 1 ⎢ 1 ⎥ 1 = ⎣ ⎦ + = .002651 T2 44,020 373 T2 = 377 2. From table A5, calculate the Henry’s Law constant (i.e., equilibrium constant) for dissolving of NH3(g) in water at 298 K and 340 K. It should have units of Matm-1;What would it be in atm per mole fraction, as in Table 5.1 at 298 K? o For NH3(g) ----> NH3(aq) ΔG = -26.5 - (-16.45) = -10.05 kJ/mol ΔG0 − [NH (aq)] K = e RT = 0.0173 = 3 This is Henry’s Law. It says that at equilibrium the ratio of dissolved P NH3 NH3 to the partial pressure of NH3 gas in contact with the liquid is a constant = 0.0173 (Henry’s Law Constant). This also says [NH3(aq)] =0.0173PNH3 or -1 PNH3 = 0.0173 [NH3(aq)] = 57.8 atm/M x [NH3(aq)] The latter form is like Table 5.1 except it has NH3 concentration in M instead of XNH3. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS Introductory Information C

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS Introductory Information C. L. Young, R. Battino, and H. L. Clever INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the literature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uniform format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of sufficient accuracy are available values are recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation is given to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are published on consecutive pages. The following paper by E. Wilhelm gives a rigorous thermodynamic treatment on the solubility of gases in liquids. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solubility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas-liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solubility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the criti cal temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solubility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the particular worker concerned. -

Producing Nitrogen Via Pressure Swing Adsorption

Reactions and Separations Producing Nitrogen via Pressure Swing Adsorption Svetlana Ivanova Pressure swing adsorption (PSA) can be a Robert Lewis Air Products cost-effective method of onsite nitrogen generation for a wide range of purity and flow requirements. itrogen gas is a staple of the chemical industry. effective, and convenient for chemical processors. Multiple Because it is an inert gas, nitrogen is suitable for a nitrogen technologies and supply modes now exist to meet a Nwide range of applications covering various aspects range of specifications, including purity, usage pattern, por- of chemical manufacturing, processing, handling, and tability, footprint, and power consumption. Choosing among shipping. Due to its low reactivity, nitrogen is an excellent supply options can be a challenge. Onsite nitrogen genera- blanketing and purging gas that can be used to protect valu- tors, such as pressure swing adsorption (PSA) or membrane able products from harmful contaminants. It also enables the systems, can be more cost-effective than traditional cryo- safe storage and use of flammable compounds, and can help genic distillation or stored liquid nitrogen, particularly if an prevent combustible dust explosions. Nitrogen gas can be extremely high purity (e.g., 99.9999%) is not required. used to remove contaminants from process streams through methods such as stripping and sparging. Generating nitrogen gas Because of the widespread and growing use of nitrogen Industrial nitrogen gas can be produced by either in the chemical process industries (CPI), industrial gas com- cryogenic fractional distillation of liquefied air, or separa- panies have been continually improving methods of nitrogen tion of gaseous air using adsorption or permeation. -

The Basics of Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium (Or Why the Tripoli L2 Tech Question #30 Is Wrong)

The Basics of Vapor-Liquid Equilibrium (Or why the Tripoli L2 tech question #30 is wrong) A question on the Tripoli L2 exam has the wrong answer? Yes, it does. What is this errant question? 30.Above what temperature does pressurized nitrous oxide change to a gas? a. 97°F b. 75°F c. 37°F The correct answer is: d. all of the above. The answer that is considered correct, however, is: a. 97ºF. This is the critical temperature above which N2O is neither a gas nor a liquid; it is a supercritical fluid. To understand what this means and why the correct answer is “all of the above” you have to know a little about the behavior of liquids and gases. Most people know that water boils at 212ºF. Most people also know that when you’re, for instance, boiling an egg in the mountains, you have to boil it longer to fully cook it. The reason for this has to do with the vapor pressure of water. Every liquid wants to vaporize to some extent. The measure of this tendency is known as the vapor pressure and varies as a function of temperature. When the vapor pressure of a liquid reaches the pressure above it, it boils. Until then, it evaporates until the fraction of vapor in the mixture above it is equal to the ratio of the vapor pressure to the total pressure. At that point it is said to be in equilibrium and no further liquid will evaporate. The vapor pressure of water at 212ºF is 14.696 psi – the atmospheric pressure at sea level. -

Lecture 15: 11.02.05 Phase Changes and Phase Diagrams of Single- Component Materials

3.012 Fundamentals of Materials Science Fall 2005 Lecture 15: 11.02.05 Phase changes and phase diagrams of single- component materials Figure removed for copyright reasons. Source: Abstract of Wang, Xiaofei, Sandro Scandolo, and Roberto Car. "Carbon Phase Diagram from Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics." Physical Review Letters 95 (2005): 185701. Today: LAST TIME .........................................................................................................................................................................................2� BEHAVIOR OF THE CHEMICAL POTENTIAL/MOLAR FREE ENERGY IN SINGLE-COMPONENT MATERIALS........................................4� The free energy at phase transitions...........................................................................................................................................4� PHASES AND PHASE DIAGRAMS SINGLE-COMPONENT MATERIALS .................................................................................................6� Phases of single-component materials .......................................................................................................................................6� Phase diagrams of single-component materials ........................................................................................................................6� The Gibbs Phase Rule..................................................................................................................................................................7� Constraints on the shape of -

Phase Diagrams

Module-07 Phase Diagrams Contents 1) Equilibrium phase diagrams, Particle strengthening by precipitation and precipitation reactions 2) Kinetics of nucleation and growth 3) The iron-carbon system, phase transformations 4) Transformation rate effects and TTT diagrams, Microstructure and property changes in iron- carbon system Mixtures – Solutions – Phases Almost all materials have more than one phase in them. Thus engineering materials attain their special properties. Macroscopic basic unit of a material is called component. It refers to a independent chemical species. The components of a system may be elements, ions or compounds. A phase can be defined as a homogeneous portion of a system that has uniform physical and chemical characteristics i.e. it is a physically distinct from other phases, chemically homogeneous and mechanically separable portion of a system. A component can exist in many phases. E.g.: Water exists as ice, liquid water, and water vapor. Carbon exists as graphite and diamond. Mixtures – Solutions – Phases (contd…) When two phases are present in a system, it is not necessary that there be a difference in both physical and chemical properties; a disparity in one or the other set of properties is sufficient. A solution (liquid or solid) is phase with more than one component; a mixture is a material with more than one phase. Solute (minor component of two in a solution) does not change the structural pattern of the solvent, and the composition of any solution can be varied. In mixtures, there are different phases, each with its own atomic arrangement. It is possible to have a mixture of two different solutions! Gibbs phase rule In a system under a set of conditions, number of phases (P) exist can be related to the number of components (C) and degrees of freedom (F) by Gibbs phase rule. -

Liquid-Vapor Equilibrium in a Binary System

Liquid-Vapor Equilibria in Binary Systems1 Purpose The purpose of this experiment is to study a binary liquid-vapor equilibrium of chloroform and acetone. Measurements of liquid and vapor compositions will be made by refractometry. The data will be treated according to equilibrium thermodynamic considerations, which are developed in the theory section. Theory Consider a liquid-gas equilibrium involving more than one species. By definition, an ideal solution is one in which the vapor pressure of a particular component is proportional to the mole fraction of that component in the liquid phase over the entire range of mole fractions. Note that no distinction is made between solute and solvent. The proportionality constant is the vapor pressure of the pure material. Empirically it has been found that in very dilute solutions the vapor pressure of solvent (major component) is proportional to the mole fraction X of the solvent. The proportionality constant is the vapor pressure, po, of the pure solvent. This rule is called Raoult's law: o (1) psolvent = p solvent Xsolvent for Xsolvent = 1 For a truly ideal solution, this law should apply over the entire range of compositions. However, as Xsolvent decreases, a point will generally be reached where the vapor pressure no longer follows the ideal relationship. Similarly, if we consider the solute in an ideal solution, then Eq.(1) should be valid. Experimentally, it is generally found that for dilute real solutions the following relationship is obeyed: psolute=K Xsolute for Xsolute<< 1 (2) where K is a constant but not equal to the vapor pressure of pure solute. -

Pressure Vs Temperature (Boiling Point)

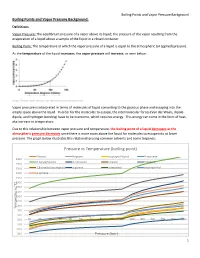

Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background: Definitions Vapor Pressure: The equilibrium pressure of a vapor above its liquid; the pressure of the vapor resulting from the evaporation of a liquid above a sample of the liquid in a closed container. Boiling Point: The temperature at which the vapor pressure of a liquid is equal to the atmospheric (or applied) pressure. As the temperature of the liquid increases, the vapor pressure will increase, as seen below: https://www.chem.purdue.edu/gchelp/liquids/vpress.html Vapor pressure is interpreted in terms of molecules of liquid converting to the gaseous phase and escaping into the empty space above the liquid. In order for the molecules to escape, the intermolecular forces (Van der Waals, dipole- dipole, and hydrogen bonding) have to be overcome, which requires energy. This energy can come in the form of heat, aka increase in temperature. Due to this relationship between vapor pressure and temperature, the boiling point of a liquid decreases as the atmospheric pressure decreases since there is more room above the liquid for molecules to escape into at lower pressure. The graph below illustrates this relationship using common solvents and some terpenes: Pressure vs Temperature (boiling point) Ethanol Heptane Isopropyl Alcohol B-myrcene 290.0 B-caryophyllene d-Limonene Linalool Pulegone 270.0 250.0 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol) a-pinene a-terpineol terpineol-4-ol 230.0 p-cymene 210.0 190.0 170.0 150.0 130.0 110.0 90.0 Temperature (˚C) Temperature 70.0 50.0 30.0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 200 300 400 500 600 760 10.0 -10.0 -30.0 Pressure (torr) 1 Boiling Points and Vapor Pressure Background As a very general rule of thumb, the boiling point of many liquids will drop about 0.5˚C for a 10mmHg decrease in pressure when operating in the region of 760 mmHg (atmospheric pressure).