Dissolved Oxygen in the Blood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solutes and Solution

Solutes and Solution The first rule of solubility is “likes dissolve likes” Polar or ionic substances are soluble in polar solvents Non-polar substances are soluble in non- polar solvents Solutes and Solution There must be a reason why a substance is soluble in a solvent: either the solution process lowers the overall enthalpy of the system (Hrxn < 0) Or the solution process increases the overall entropy of the system (Srxn > 0) Entropy is a measure of the amount of disorder in a system—entropy must increase for any spontaneous change 1 Solutes and Solution The forces that drive the dissolution of a solute usually involve both enthalpy and entropy terms Hsoln < 0 for most species The creation of a solution takes a more ordered system (solid phase or pure liquid phase) and makes more disordered system (solute molecules are more randomly distributed throughout the solution) Saturation and Equilibrium If we have enough solute available, a solution can become saturated—the point when no more solute may be accepted into the solvent Saturation indicates an equilibrium between the pure solute and solvent and the solution solute + solvent solution KC 2 Saturation and Equilibrium solute + solvent solution KC The magnitude of KC indicates how soluble a solute is in that particular solvent If KC is large, the solute is very soluble If KC is small, the solute is only slightly soluble Saturation and Equilibrium Examples: + - NaCl(s) + H2O(l) Na (aq) + Cl (aq) KC = 37.3 A saturated solution of NaCl has a [Na+] = 6.11 M and [Cl-] = -

Page 1 of 6 This Is Henry's Law. It Says That at Equilibrium the Ratio of Dissolved NH3 to the Partial Pressure of NH3 Gas In

CHMY 361 HANDOUT#6 October 28, 2012 HOMEWORK #4 Key Was due Friday, Oct. 26 1. Using only data from Table A5, what is the boiling point of water deep in a mine that is so far below sea level that the atmospheric pressure is 1.17 atm? 0 ΔH vap = +44.02 kJ/mol H20(l) --> H2O(g) Q= PH2O /XH2O = K, at ⎛ P2 ⎞ ⎛ K 2 ⎞ ΔH vap ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = ln⎜ ⎟ − ⎜ − ⎟ equilibrium, i.e., the Vapor Pressure ⎝ P1 ⎠ ⎝ K1 ⎠ R ⎝ T2 T1 ⎠ for the pure liquid. ⎛1.17 ⎞ 44,020 ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = − ⎜ − ⎟ = 1 8.3145 ⎜ T 373 ⎟ ⎝ ⎠ ⎝ 2 ⎠ ⎡1.17⎤ − 8.3145ln 1 ⎢ 1 ⎥ 1 = ⎣ ⎦ + = .002651 T2 44,020 373 T2 = 377 2. From table A5, calculate the Henry’s Law constant (i.e., equilibrium constant) for dissolving of NH3(g) in water at 298 K and 340 K. It should have units of Matm-1;What would it be in atm per mole fraction, as in Table 5.1 at 298 K? o For NH3(g) ----> NH3(aq) ΔG = -26.5 - (-16.45) = -10.05 kJ/mol ΔG0 − [NH (aq)] K = e RT = 0.0173 = 3 This is Henry’s Law. It says that at equilibrium the ratio of dissolved P NH3 NH3 to the partial pressure of NH3 gas in contact with the liquid is a constant = 0.0173 (Henry’s Law Constant). This also says [NH3(aq)] =0.0173PNH3 or -1 PNH3 = 0.0173 [NH3(aq)] = 57.8 atm/M x [NH3(aq)] The latter form is like Table 5.1 except it has NH3 concentration in M instead of XNH3. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS Introductory Information C

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS Introductory Information C. L. Young, R. Battino, and H. L. Clever INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the literature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uniform format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of sufficient accuracy are available values are recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation is given to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are published on consecutive pages. The following paper by E. Wilhelm gives a rigorous thermodynamic treatment on the solubility of gases in liquids. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solubility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas-liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solubility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the criti cal temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solubility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the particular worker concerned. -

Producing Nitrogen Via Pressure Swing Adsorption

Reactions and Separations Producing Nitrogen via Pressure Swing Adsorption Svetlana Ivanova Pressure swing adsorption (PSA) can be a Robert Lewis Air Products cost-effective method of onsite nitrogen generation for a wide range of purity and flow requirements. itrogen gas is a staple of the chemical industry. effective, and convenient for chemical processors. Multiple Because it is an inert gas, nitrogen is suitable for a nitrogen technologies and supply modes now exist to meet a Nwide range of applications covering various aspects range of specifications, including purity, usage pattern, por- of chemical manufacturing, processing, handling, and tability, footprint, and power consumption. Choosing among shipping. Due to its low reactivity, nitrogen is an excellent supply options can be a challenge. Onsite nitrogen genera- blanketing and purging gas that can be used to protect valu- tors, such as pressure swing adsorption (PSA) or membrane able products from harmful contaminants. It also enables the systems, can be more cost-effective than traditional cryo- safe storage and use of flammable compounds, and can help genic distillation or stored liquid nitrogen, particularly if an prevent combustible dust explosions. Nitrogen gas can be extremely high purity (e.g., 99.9999%) is not required. used to remove contaminants from process streams through methods such as stripping and sparging. Generating nitrogen gas Because of the widespread and growing use of nitrogen Industrial nitrogen gas can be produced by either in the chemical process industries (CPI), industrial gas com- cryogenic fractional distillation of liquefied air, or separa- panies have been continually improving methods of nitrogen tion of gaseous air using adsorption or permeation. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS INTRODUCTION the Solubility Data Project Aims to Make a Comprehensive Search of the Lit- Erat

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS R. Battino, H. L. Clever and C. L. Young INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the lit erature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uni form format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of suf ficient accuracy are available values recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation suggested to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are pUblished on consecutive pages. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solUbility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solUbility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the critical temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solu bility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the par ticular worker concerned. The difficulty partly stems from our inability to rigorously distinguish between a gas, a vapor, and a liquid, which has been discussed in numerous textbooks. -

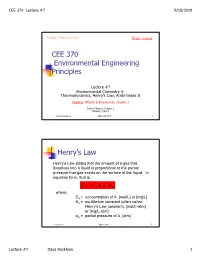

CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Henry's

CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Updated: 18 September 2019 Print version CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Lecture #7 Environmental Chemistry V: Thermodynamics, Henry’s Law, Acids-bases II Reading: Mihelcic & Zimmerman, Chapter 3 Davis & Masten, Chapter 2 Mihelcic, Chapt 3 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 1 Henry’s Law Henry's Law states that the amount of a gas that dissolves into a liquid is proportional to the partial pressure that gas exerts on the surface of the liquid. In equation form, that is: C AH = K p A where, CA = concentration of A, [mol/L] or [mg/L] KH = equilibrium constant (often called Henry's Law constant), [mol/L-atm] or [mg/L-atm] pA = partial pressure of A, [atm] David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 2 Lecture #7 Dave Reckhow 1 CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Henry’s Law Constants Reaction Name Kh, mol/L-atm pKh = -log Kh -2 CO2(g) _ CO2(aq) Carbon 3.41 x 10 1.47 dioxide NH3(g) _ NH3(aq) Ammonia 57.6 -1.76 -1 H2S(g) _ H2S(aq) Hydrogen 1.02 x 10 0.99 sulfide -3 CH4(g) _ CH4(aq) Methane 1.50 x 10 2.82 -3 O2(g) _ O2(aq) Oxygen 1.26 x 10 2.90 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 3 Example: Solubility of O2 in Water Background Although the atmosphere we breathe is comprised of approximately 20.9 percent oxygen, oxygen is only slightly soluble in water. In addition, the solubility decreases as the temperature increases. -

Getting the Other Gas Laws

Getting the other gas laws If temperature is constant If volume is constant you you get Boyle’s Law get Gay-Lussac’s Law P1 P2 P1V1 = P2V2 = T1 T2 If pressure is constant you get Charles’s Law If all are variable, you get the Combined Gas Law. V V2 1 = P1V1 P2V2 T1 T2 = T1 T2 Boyle’s Law: Inverse relationship between Pressure and Volume. P1V1 = P2V2 P V Combined Gas Law: Gay-Lussac’s Law: P V P V Charles’ Law: 1 1 = 2 2 Direct relationship between T1 T2 Direct relationship between Temperature and Pressure. Temperature and Volume. P P V V 1 = 2 1 = 2 T1 T2 T1 T2 (T must be in Kelvin) T Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures He found that in the absence of a chemical reaction, the pressure of a gas mixture is the sum of the individual pressures of each gas alone The pressure of each gas in a mixture is called the partial pressure of that gas Dalton’s law of partial pressures the total pressure of a mixture of gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of the component gases The law is true regardless of the number of different gases that are present Dalton’s law may be expressed as PT = P1 + P2 + P3 +… Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures What is the total pressure in the cylinder? Ptotal in gas mixture = P1 + P2 + ... Dalton’s Law: total P is sum of pressures. Gases Collected by Water Displacement Gases produced in the laboratory are often collected over water Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures The gas produced by the reaction displaces the water, which is more dense, in the collection bottle You can apply Dalton’s law of partial -

PRESSURE SWING ADSORPTION in the UNIT OPERATIONS LABORATORY Jason C

ChE laboratory PRESSURE SWING ADSORPTION IN THE UNIT OPERATIONS LABORATORY Jason C. Ganley Colorado School of Mines • Golden, CO 80401 ressure swing adsorption (PSA) is an industrial process adsorption occurs. The selection of a particular type of ad- typically used for the bulk separation of gas mixtures. sorbent may allow one component of a gas mixture to be An outgrowth of temperature swing adsorption, PSA preferentially adsorbed, the nature of surface and/or pore dif- Pis one of only a few gas-surface adsorption processes that fusion effects may vary for each gas in the mixture, and so on. allows for the separation of mixtures of gaseous species or PSA is a cyclic operation, and generally involves separa- vapors that exist in relatively high (non-trace) concentra- tion of a gas mixture by taking advantage of differences in tions in respect to one another. PSA has also been coupled adsorption thermodynamics or in diffusion rates that exist for to distillation processes for the separation of alcohol-water its various components. Cycling between higher and lower [1] vapor azeotropes. pressures allows components of the gas mixture to be removed It is interesting to note that, despite serving an important from (and later released to) the gas phase over designated pe- role for many decades in the chemical process industry, PSA riods of time. Students in the Unit Operations Laboratory may is not a central topic discussed in most chemical engineering consider the PSA cycle primarily as a mass transfer (rather educational resources, which instead focus on mass transfer than heat transfer) experiment. -

Raoult's Law – Partition Law

BAE 820 Physical Principles of Environmental Systems Henry’s Law - Raoult's Law – Partition law Dr. Zifei Liu Biological and Agricultural Engineering Henry's law • At a constant temperature, the amount of a given gas that dissolves in a given type and volume of liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of that gas in equilibrium with that liquid. Pi = KHCi • Where Pi is the partial pressure of the gaseous solute above the solution, C is the i William Henry concentration of the dissolved gas and KH (1774-1836) is Henry’s constant with the dimensions of pressure divided by concentration. KH is different for each solute-solvent pair. Biological and Agricultural Engineering 2 Henry's law For a gas mixture, Henry's law helps to predict the amount of each gas which will go into solution. When a gas is in contact with the surface of a liquid, the amount of the gas which will go into solution is proportional to the partial pressure of that gas. An equivalent way of stating the law is that the solubility of a gas in a liquid is directly proportional to the partial pressure of the gas above the liquid. the solubility of gases generally decreases with increasing temperature. A simple rationale for Henry's law is that if the partial pressure of a gas is twice as high, then on the average twice as many molecules will hit the liquid surface in a given time interval, Biological and Agricultural Engineering 3 Air-water equilibrium Dissolution Pg or Cg Air (atm, Pa, mol/L, ppm, …) At equilibrium, Pg KH = Caq Water Caq (mol/L, mole ratio, ppm, …) Volatilization Biological and Agricultural Engineering 4 Various units of the Henry’s constant (gases in water at 25ºC) Form of K =P/C K =C /P K =P/x K =C /C equation H, pc aq H, cp aq H, px H, cc aq gas Units L∙atm/mol mol/(L∙atm) atm dimensionless -3 4 -2 O2 769 1.3×10 4.26×10 3.18×10 -4 4 -2 N2 1639 6.1×10 9.08×10 1.49×10 -2 3 CO2 29 3.4×10 1.63×10 0.832 Since all KH may be referred to as Henry's law constants, we must be quite careful to check the units, and note which version of the equation is being used. -

An Introduction to Chapter 16: “Methods for Estimating Air Emissions from Chemical Manufacturing Facilities”

An Introduction to Chapter 16: “Methods for Estimating Air Emissions from Chemical Manufacturing Facilities” John Allen Hatfield Mitchell Scientific, Inc. PO Box 2605 Westfield, NJ 07091-2605 [email protected] Abstract Chemical processing plays an integral part in most manufacturing operations. While the purpose of each industry is to meet different manufacturing objectives, most chemical processes include at least one or more of the four common operations: preassembly, reaction, isolation, and purification. Process operations may be continuous in nature and operate for long periods of time or they may consist of many discrete events and operate in a batch wise fashion. Measuring the air emissions from a boiler or other combustion operation is largely accomplished through stack sampling and analysis. However, assessing the air emissions that occur from a chemical process is much more involved since the process takes place at different intervals throughout the manufacturing operation. The emissions that occur during a combustion operation are fairly predictable and largely dependent upon the fuel that is being used and the boiler performance. Emissions that occur during a chemical process depend upon the solvents that are used, the chemicals that required as well as the specific types of unit operations that are followed. Having established calculation procedures that can be applied to all chemical processes without regard to industry is important because it standardizes the environmental analysis while at the same time normalizes environmental regulations. The purpose of this document is to review many of the air emission calculation models that are contained in EIIP Document Chapter 16: Methods for Estimating Air Emissions from Chemical Manufacturing Facilities , August 2007. -

Respiratory Gas Exchange in the Lungs

RESPIRATORY GAS EXCHANGE Alveolar PO2 = 105 mmHg; Pulmonary artery PO2 = 40 mmHg PO2 gradient across respiratory membrane 65 mmHg (105 mmHg – 40 mmHg) Results in pulmonary vein PO2 ~100 mmHg Partial Pressures of Respiratory Gases • According to Dalton’s law, in a gas mixture, the pressure exerted by each individual gas is independent of the pressures of other gases in the mixture. • The partial pressure of a particular gas is equal to its fractional concentration times the total pressure of all the gases in the mixture. • Atmospheric air : Oxygen constitutes 20.93% of dry atmospheric air. At a standard barometric pressure of 760 mm Hg, PO2 = 0.2093 × 760 mm Hg = 159 mm Hg Similarly , PCO2= 0.3 mm Hg PN2= 600 mm Hg Inspired Air: PIO2= FIO2 (PB-PH2O)= 0.2093 (760-47)= 149 mm Hg PICO2= 0.3 mm Hg PIN2= 564 mm Hg Alveolar air at standard barometric pressure • 2.5 to 3 L of gas is already in the lungs at the FRC and the approximately 350 mL per breath enters the alveoli with every breath. • About 250 mL of oxygen continuously diffuses from the alveoli into the pulmonary capillary blood per minute at rest and 200 mL of carbon dioxide diffuses from the mixed venous blood in the pulmonary capillaries into the alveoli per minute. • The PO2 and PCO2 of mixed venous blood are about 40 mm Hg and 45 to 46 mm Hg, respectively • The PO2 and PCO2 in the alveolar air are determined by the alveolar ventilation, the pulmonary capillary perfusion, the oxygen consumption, and the carbon dioxide production. -

Introduction to Aviation Physiology

FOREWORD Aviation Physiology deals with the physical and mental effects of flight on air crew personnel and passengers. Study of this booklet will familiarize you with some of the physiological problems of flight, and will instruct you in the use of some of the devices that aviation physiologists and others have developed to assist in human compensation for the numerous environmental changes that are encountered in flight. For most of you, Aviation Physiology is an entirely new field. To others, it is something that you were taught while in military service or elsewhere. This booklet should be used as a reference during your flying career. Remember, every human is physiologically different and can react differently in any given situation. It is our sincere hope that we can enlighten, stimulate, and assist you during your brief stay with us. After you have returned to your regular routine, remember that we at the Civil Aeromedical Institute will be able to assist you with problems concerning Aviation Physiology. Inquiries should be addressed to: Federal Aviation Administration Civil Aerospace Medical Institute Aeromedical Education Division, AAM-400 Mike Monroney Aeronautical Center P.O. Box 25082 Oklahoma City, OK 73125 Phone: (405) 954-4837 Fax: (405) 954-8016 i INTRODUCTION TO AVIATION PHYSIOLOGY Human beings have the remarkable ability to adapt to their environment. The human body makes adjustments for changes in external temperature, acclimates to barometric pressure variations from one habitat to another, compensates for motion in space and postural changes in relation to gravity, and performs all of these adjustments while meeting changing energy requirements for varying amounts of physical and mental activity.