Producing Nitrogen Via Pressure Swing Adsorption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solutes and Solution

Solutes and Solution The first rule of solubility is “likes dissolve likes” Polar or ionic substances are soluble in polar solvents Non-polar substances are soluble in non- polar solvents Solutes and Solution There must be a reason why a substance is soluble in a solvent: either the solution process lowers the overall enthalpy of the system (Hrxn < 0) Or the solution process increases the overall entropy of the system (Srxn > 0) Entropy is a measure of the amount of disorder in a system—entropy must increase for any spontaneous change 1 Solutes and Solution The forces that drive the dissolution of a solute usually involve both enthalpy and entropy terms Hsoln < 0 for most species The creation of a solution takes a more ordered system (solid phase or pure liquid phase) and makes more disordered system (solute molecules are more randomly distributed throughout the solution) Saturation and Equilibrium If we have enough solute available, a solution can become saturated—the point when no more solute may be accepted into the solvent Saturation indicates an equilibrium between the pure solute and solvent and the solution solute + solvent solution KC 2 Saturation and Equilibrium solute + solvent solution KC The magnitude of KC indicates how soluble a solute is in that particular solvent If KC is large, the solute is very soluble If KC is small, the solute is only slightly soluble Saturation and Equilibrium Examples: + - NaCl(s) + H2O(l) Na (aq) + Cl (aq) KC = 37.3 A saturated solution of NaCl has a [Na+] = 6.11 M and [Cl-] = -

Environmental Quality: in Situ Air Sparging

EM 200-1-19 31 December 2013 Environmental Quality IN-SITU AIR SPARGING ENGINEER MANUAL AVAILABILITY Electronic copies of this and other U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) publications are available on the Internet at http://www.publications.usace.army.mil/ This site is the only repository for all official USACE regulations, circulars, manuals, and other documents originating from HQUSACE. Publications are provided in portable document format (PDF). This document is intended solely as guidance. The statutory provisions and promulgated regulations described in this document contain legally binding requirements. This document is not a legally enforceable regulation itself, nor does it alter or substitute for those legal provisions and regulations it describes. Thus, it does not impose any legally binding requirements. This guidance does not confer legal rights or impose legal obligations upon any member of the public. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the discussion in this document, the obligations of the regulated community are determined by statutes, regulations, or other legally binding requirements. In the event of a conflict between the discussion in this document and any applicable statute or regulation, this document would not be controlling. This document may not apply to a particular situation based upon site- specific circumstances. USACE retains the discretion to adopt approaches on a case-by-case basis that differ from those described in this guidance where appropriate and legally consistent. This document may be revised periodically without public notice. DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY EM 200-1-19 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers CEMP-CE Washington, D.C. -

Page 1 of 6 This Is Henry's Law. It Says That at Equilibrium the Ratio of Dissolved NH3 to the Partial Pressure of NH3 Gas In

CHMY 361 HANDOUT#6 October 28, 2012 HOMEWORK #4 Key Was due Friday, Oct. 26 1. Using only data from Table A5, what is the boiling point of water deep in a mine that is so far below sea level that the atmospheric pressure is 1.17 atm? 0 ΔH vap = +44.02 kJ/mol H20(l) --> H2O(g) Q= PH2O /XH2O = K, at ⎛ P2 ⎞ ⎛ K 2 ⎞ ΔH vap ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = ln⎜ ⎟ − ⎜ − ⎟ equilibrium, i.e., the Vapor Pressure ⎝ P1 ⎠ ⎝ K1 ⎠ R ⎝ T2 T1 ⎠ for the pure liquid. ⎛1.17 ⎞ 44,020 ⎛ 1 1 ⎞ ln⎜ ⎟ = − ⎜ − ⎟ = 1 8.3145 ⎜ T 373 ⎟ ⎝ ⎠ ⎝ 2 ⎠ ⎡1.17⎤ − 8.3145ln 1 ⎢ 1 ⎥ 1 = ⎣ ⎦ + = .002651 T2 44,020 373 T2 = 377 2. From table A5, calculate the Henry’s Law constant (i.e., equilibrium constant) for dissolving of NH3(g) in water at 298 K and 340 K. It should have units of Matm-1;What would it be in atm per mole fraction, as in Table 5.1 at 298 K? o For NH3(g) ----> NH3(aq) ΔG = -26.5 - (-16.45) = -10.05 kJ/mol ΔG0 − [NH (aq)] K = e RT = 0.0173 = 3 This is Henry’s Law. It says that at equilibrium the ratio of dissolved P NH3 NH3 to the partial pressure of NH3 gas in contact with the liquid is a constant = 0.0173 (Henry’s Law Constant). This also says [NH3(aq)] =0.0173PNH3 or -1 PNH3 = 0.0173 [NH3(aq)] = 57.8 atm/M x [NH3(aq)] The latter form is like Table 5.1 except it has NH3 concentration in M instead of XNH3. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS Introductory Information C

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS Introductory Information C. L. Young, R. Battino, and H. L. Clever INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the literature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uniform format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of sufficient accuracy are available values are recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation is given to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are published on consecutive pages. The following paper by E. Wilhelm gives a rigorous thermodynamic treatment on the solubility of gases in liquids. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solubility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas-liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solubility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the criti cal temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solubility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the particular worker concerned. -

THE SOLUBILITY of GASES in LIQUIDS INTRODUCTION the Solubility Data Project Aims to Make a Comprehensive Search of the Lit- Erat

THE SOLUBILITY OF GASES IN LIQUIDS R. Battino, H. L. Clever and C. L. Young INTRODUCTION The Solubility Data Project aims to make a comprehensive search of the lit erature for data on the solubility of gases, liquids and solids in liquids. Data of suitable accuracy are compiled into data sheets set out in a uni form format. The data for each system are evaluated and where data of suf ficient accuracy are available values recommended and in some cases a smoothing equation suggested to represent the variation of solubility with pressure and/or temperature. A text giving an evaluation and recommended values and the compiled data sheets are pUblished on consecutive pages. DEFINITION OF GAS SOLUBILITY The distinction between vapor-liquid equilibria and the solUbility of gases in liquids is arbitrary. It is generally accepted that the equilibrium set up at 300K between a typical gas such as argon and a liquid such as water is gas liquid solubility whereas the equilibrium set up between hexane and cyclohexane at 350K is an example of vapor-liquid equilibrium. However, the distinction between gas-liquid solUbility and vapor-liquid equilibrium is often not so clear. The equilibria set up between methane and propane above the critical temperature of methane and below the critical temperature of propane may be classed as vapor-liquid equilibrium or as gas-liquid solu bility depending on the particular range of pressure considered and the par ticular worker concerned. The difficulty partly stems from our inability to rigorously distinguish between a gas, a vapor, and a liquid, which has been discussed in numerous textbooks. -

Dissolved Oxygen in the Blood

Chapter 1 – Dissolved Oxygen in the Blood Say we have a volume of blood, which we’ll represent as a beaker of fluid. Now let’s include oxygen in the gas above the blood (represented by the green circles). The oxygen exerts a certain amount of partial pressure, which is a measure of the concentration of oxygen in the gas (represented by the pink arrows). This pressure causes some of the oxygen to become dissolved in the blood. If we raise the concentration of oxygen in the gas, it will have a higher partial pressure, and consequently more oxygen will become dissolved in the blood. Keep in mind that what we are describing is a dynamic process, with oxygen coming in and out of the blood all the time, in order to maintain a certain concentration of dissolved oxygen. This is known as a) low partial pressure of oxygen b) high partial pressure of oxygen dynamic equilibrium. As you might expect, lowering the oxygen concentration in the gas would lower its partial pressure and a new equilibrium would be established with a lower dissolved oxygen concentration. In fact, the concentration of DISSOLVED oxygen in the blood (the CdO2) is directly proportional to the partial pressure of oxygen (the PO2) in the gas. This is known as Henry's Law. In this equation, the constant of proportionality is called the solubility coefficient of oxygen in blood (aO2). It is equal to 0.0031 mL / mmHg of oxygen / dL of blood. With these units, the dissolved oxygen concentration must be measured in mL / dL of blood, and the partial pressure of oxygen must be measured in mmHg. -

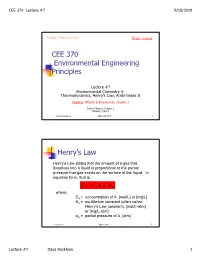

CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Henry's

CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Updated: 18 September 2019 Print version CEE 370 Environmental Engineering Principles Lecture #7 Environmental Chemistry V: Thermodynamics, Henry’s Law, Acids-bases II Reading: Mihelcic & Zimmerman, Chapter 3 Davis & Masten, Chapter 2 Mihelcic, Chapt 3 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 1 Henry’s Law Henry's Law states that the amount of a gas that dissolves into a liquid is proportional to the partial pressure that gas exerts on the surface of the liquid. In equation form, that is: C AH = K p A where, CA = concentration of A, [mol/L] or [mg/L] KH = equilibrium constant (often called Henry's Law constant), [mol/L-atm] or [mg/L-atm] pA = partial pressure of A, [atm] David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 2 Lecture #7 Dave Reckhow 1 CEE 370 Lecture #7 9/18/2019 Henry’s Law Constants Reaction Name Kh, mol/L-atm pKh = -log Kh -2 CO2(g) _ CO2(aq) Carbon 3.41 x 10 1.47 dioxide NH3(g) _ NH3(aq) Ammonia 57.6 -1.76 -1 H2S(g) _ H2S(aq) Hydrogen 1.02 x 10 0.99 sulfide -3 CH4(g) _ CH4(aq) Methane 1.50 x 10 2.82 -3 O2(g) _ O2(aq) Oxygen 1.26 x 10 2.90 David Reckhow CEE 370 L#7 3 Example: Solubility of O2 in Water Background Although the atmosphere we breathe is comprised of approximately 20.9 percent oxygen, oxygen is only slightly soluble in water. In addition, the solubility decreases as the temperature increases. -

"Determination of Total Organic Carbon and Specific UV

EPA Document #: EPA/600/R-05/055 METHOD 415.3 DETERMINATION OF TOTAL ORGANIC CARBON AND SPECIFIC UV ABSORBANCE AT 254 nm IN SOURCE WATER AND DRINKING WATER Revision 1.1 February, 2005 B. B. Potter, USEPA, Office of Research and Development, National Exposure Research Laboratory J. C. Wimsatt, The National Council On The Aging, Senior Environmental Employment Program NATIONAL EXPOSURE RESEARCH LABORATORY OFFICE OF RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION AGENCY CINCINNATI, OHIO 45268 415.3 - 1 METHOD 415.3 DETERMINATION OF TOTAL ORGANIC CARBON AND SPECIFIC UV ABSORBANCE AT 254 nm IN SOURCE WATER AND DRINKING WATER 1.0 SCOPE AND APPLICATION 1.1 This method provides procedures for the determination of total organic carbon (TOC), dissolved organic carbon (DOC), and UV absorption at 254 nm (UVA) in source waters and drinking waters. The DOC and UVA determinations are used in the calculation of the Specific UV Absorbance (SUVA). For TOC and DOC analysis, the sample is acidified and the inorganic carbon (IC) is removed prior to analysis for organic carbon (OC) content using a TOC instrument system. The measurements of TOC and DOC are based on calibration with potassium hydrogen phthalate (KHP) standards. This method is not intended for use in the analysis of treated or untreated industrial wastewater discharges as those wastewater samples may damage or contaminate the instrument system(s). 1.2 The three (3) day, pooled organic carbon detection limit (OCDL) is based on the detection limit (DL) calculation.1 It is a statistical determination of precision, and may be below the level of quantitation. -

The Liquefaction of Helium., In: KNAW, Proceedings, 11, 1908-1909, Amsterdam, 1909, Pp

Huygens Institute - Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW) Citation: H. Kamerlingh Onnes, The liquefaction of helium., in: KNAW, Proceedings, 11, 1908-1909, Amsterdam, 1909, pp. 168-185 This PDF was made on 24 September 2010, from the 'Digital Library' of the Dutch History of Science Web Center (www.dwc.knaw.nl) > 'Digital Library > Proceedings of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW), http://www.digitallibrary.nl' - 1 - ( 16B ) The Ieftha,nd part agrees then perfectly with BAKHUIS ROOZEBOOl\I)S spacial figul'e, 0 A and OB not representing the melting-points under vapour-pressure, but the tra,nsition points of the two components under vapoul' pressure, i. e. the points where the ordinary cl'ystalline state passes to the tIuid cl'ystalline state under t11e pressure of its vapour. If this spacial figm'e is cut by a plane of constant pressnre, we get, at least if this pressure is chosen high en'ough, the simplest imaginabie T-X-fignre of a system of two components, each of which possesses a stabie fluid-crystalline modification. The other possible cases may be easily derived from this spaeial figure. Amste1,dam June 1908. Anol'g. LYtem. Laboratorium of the University. Physics. - "Tlte liquefaction of helium". By Prof. H. KAIIIERLINGH ONNES. Oommunication N°. 108 from the Physical Laboratory at Leiden. 9 1. Met/wd. As a fil'st step on the road towards the liquefaction of helium the theory of VAN DER ·WAALS indicated the determination of its isotherms, particularly for the tempel'atures which are to be attained by means of l~quid hydl'ogen. -

Louis Paul Cailletet-The Liquefaction of the Permanent Gases

Educator Indian Journal of Chemi cal Techn ology Vol. I 0. March 20m. pp. 22:l-23(i Louis Paul Cailletet-The liquefaction of the permanent gases 1 Jaime Wi sniak ' ' Department of Chemical Engi neering. 13cn-G urion Universi ty or the cgcv. Bccr-S hcva. Israel R4 10.') To Louis Paul Ca illetct ( l lD 1- 1913) we owe th e rea lization of th e liquefaction of perma nent gases using a free expa n sion process. A brillian t analysis of an ex perimental mishap led him to ac hieve thi s possib ility. The priority or oxygen lique faction was and continues to be a matter of disc uss ion. The life and sc ientific work or Caillctet arc descri bed toget her w ith detai ls about the priority polem ic. 4 Mankind has been interes ted in quantifying th e differ through the wai Is of th e vesse l . However, if th e I iq ence bet ween hot and cold si nee very old times. The uid evaporated into a vacuum surrounded by a freez ori gi nal apparatus, ca lled th ennoscopes, served ing mi xture th e cooling effec t could be increased in merely to show the changes in th e ten~perature of its definitely as long as the liquid exerted an appreciable surroundings. Eventually th e need arose for qu anti vapour pressure. John Leslie ( 1766-1 832) not on ly fying these observations and th e eli fferent th ermome had been able to freeze water by absorbing its vapour ters began to be developed. -

Getting the Other Gas Laws

Getting the other gas laws If temperature is constant If volume is constant you you get Boyle’s Law get Gay-Lussac’s Law P1 P2 P1V1 = P2V2 = T1 T2 If pressure is constant you get Charles’s Law If all are variable, you get the Combined Gas Law. V V2 1 = P1V1 P2V2 T1 T2 = T1 T2 Boyle’s Law: Inverse relationship between Pressure and Volume. P1V1 = P2V2 P V Combined Gas Law: Gay-Lussac’s Law: P V P V Charles’ Law: 1 1 = 2 2 Direct relationship between T1 T2 Direct relationship between Temperature and Pressure. Temperature and Volume. P P V V 1 = 2 1 = 2 T1 T2 T1 T2 (T must be in Kelvin) T Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures He found that in the absence of a chemical reaction, the pressure of a gas mixture is the sum of the individual pressures of each gas alone The pressure of each gas in a mixture is called the partial pressure of that gas Dalton’s law of partial pressures the total pressure of a mixture of gases is equal to the sum of the partial pressures of the component gases The law is true regardless of the number of different gases that are present Dalton’s law may be expressed as PT = P1 + P2 + P3 +… Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures What is the total pressure in the cylinder? Ptotal in gas mixture = P1 + P2 + ... Dalton’s Law: total P is sum of pressures. Gases Collected by Water Displacement Gases produced in the laboratory are often collected over water Dalton’s Law of Partial Pressures The gas produced by the reaction displaces the water, which is more dense, in the collection bottle You can apply Dalton’s law of partial -

Developed and Maintained by the NFCC Contents

Developed and maintained by the NFCC Contents The gas laws ................................................................................................................................................. 3 The liquefaction of gases ..................................................................................................................... 3 Critical temperature and pressure .................................................................................................... 4 Liquefied gases in cylinders ................................................................................................................ 4 Sublimation ........................................................................................................................................... 5 This content is only valid at the time of download - 4-10-2021 00:25 2 of 5 The gas laws There are three gas laws: Boyle's Law – for a gas at constant temperature, the volume of a gas is inversely proportional to the pressure upon it. If V1 and P1 are the initial volume and pressure, and V2 and P2 are the final volumes and pressure, then V1 x P1 = V2 x P2 Charles' Law – the volume of a given mass of gas at constant pressure increases by 1/273 of its volume for every 1°C rise in temperature. The relationship between volume and temperature is: V1 / T1 = V2 / T2 where V1 and T1 are the initial volume and absolute temperature and V2 and T2 are the final volume and absolute temperature (the Kelvin temperature, not the Celsius temperature). In other words, the volume of