Imperial Throne Halls and Discourse of Power in the Topography of Early Modern Russia (Late 17Th–18Th Centuries)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meat: a Novel

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Faculty Publications 2019 Meat: A Novel Sergey Belyaev Boris Pilnyak Ronald D. LeBlanc University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Belyaev, Sergey; Pilnyak, Boris; and LeBlanc, Ronald D., "Meat: A Novel" (2019). Faculty Publications. 650. https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs/650 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sergey Belyaev and Boris Pilnyak Meat: A Novel Translated by Ronald D. LeBlanc Table of Contents Acknowledgments . III Note on Translation & Transliteration . IV Meat: A Novel: Text and Context . V Meat: A Novel: Part I . 1 Meat: A Novel: Part II . 56 Meat: A Novel: Part III . 98 Memorandum from the Authors . 157 II Acknowledgments I wish to thank the several friends and colleagues who provided me with assistance, advice, and support during the course of my work on this translation project, especially those who helped me to identify some of the exotic culinary items that are mentioned in the opening section of Part I. They include Lynn Visson, Darra Goldstein, Joyce Toomre, and Viktor Konstantinovich Lanchikov. Valuable translation help with tricky grammatical constructions and idiomatic expressions was provided by Dwight and Liya Roesch, both while they were in Moscow serving as interpreters for the State Department and since their return stateside. -

Our Guests the Buildings of Cathedral Square

Summer in the Urals Pyotr Filippovich Ushakov is 95! You have lakes of kindness in your eyes ... The Buildings of Cathedral Square HEALTHY Body, Healthy mind First day of school Friendship Editor-in-chief : Elena V. Vatoropina 624021, Russia, Sverdlovsk region, Designers : Olga Vaganova Sysert, Novyi District, 25 Web: школа1-сысерть.рф Photographers : Maria A. Udintseva, Bruce Bertrand, Ilia D. http://friendship1.ksdk.ru/ Krivonogov, Anton S. Sharapov, Vadim Lebedev Е-mail: [email protected] Correspondents : Maria Kucheryavaya, Bruce Bertrand, Vasilina Starkova, Alexandr Buzuev, Vladislav Surin Magazine for young learners who love English and want to know it Summer is a small life ….....…....................... 4 Summer in the Urals .……………………………………...…. 4 Krimea - 2020 ..……………………………………………...…. 4 Travelling around Russia ……………………...... 5 My trip to the South of Russia ………………………...…. 5 Our Compatriots ……………..………………....….. 7 Pyotr Filippovich Ushakov is 95! ………..………........... 7 We are for healthy lifestyle! ………...……....…. 8 An annual holiday for tourists ..………...……….…….... 8 School Life ………….………………………….……… 10 You have lakes of kindness in your eyes ………..…….. 10 Happy Teacher’s Day! My favourite teacher ….......... 11 Healthy body, healthy mind! ………………...….………… 12 Unusual History lessons …………………………………….. 13 Our guests …………....…………………………...….. 14 Interesting Places of Moscow: The Buildings of Cathedral Square ………………………………………….…... 14 Discussion Club ………….………………………..... 17 Is graffiti an art form? ……………………………………... 17 School uniform: -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-81227-6 - The Cambridge History of Russia, Volume 1: From Early Rus’ to 1689 Edited by Maureen Perrie Index More information Index Aadil Girey, khan of Crimea 507 three-field 293, 294 Abatis defensive line (southern frontier) 491, tools and implements 291–2 494, 497 in towns 309, 598 Abbasids, Caliphate of 51 Ahmed, khan of the Great Horde 223, 237, Abibos, St 342 321 absolutism, as model of Russian and Akakii, Bishop of Tver’ 353 Muscovite states 16 Alachev, Mansi chief 334 Acre, merchants in Kiev 122 Aland˚ islands, possible origins of Rus’ in 52, Adalbert, bishop, mission to Rus’ 58, 60 54 Adashev, Aleksei Fedorovich, courtier to Albazin, Fort, Amur river 528 Ivan IV 255 alcohol Adrian, Patriarch (d. 1700) 639 peasants’ 289 Adyg tribes 530 regulations on sale of 575, 631 Afanasii, bishop of Kholmogory, Uvet Aleksandr, bishop of Viatka 633, 636 dukhovnyi 633 Aleksandr, boyar, brother of Metropolitan Agapetus, Byzantine deacon 357, 364 Aleksei 179 ‘Agapetus doctrine’ 297, 357, 364, 389 Aleksandr Mikhailovich (d.1339) 146, 153, 154 effect on law 378, 379, 384 as prince in Pskov 140, 152, 365 agricultural products 39, 315 as prince of Vladimir 139, 140 agriculture 10, 39, 219, 309 Aleksandr Nevskii, son of Iaroslav arable 25, 39, 287 (d.1263) 121, 123, 141 crop failures 42, 540 and battle of river Neva (1240) 198 crop yields 286, 287, 294, 545 campaigns against Lithuania 145 effect on environment 29–30 and Metropolitan Kirill 149 effect of environment on 10, 38 as prince of Novgorod under Mongols 134, fences 383n. -

At T He Tsar's Table

At T he Tsar’s Table Russian Imperial Porcelain from the Raymond F. Piper Collection At the Tsar’s Table Russian Imperial Porcelain from the Raymond F. Piper Collection June 1 - August 19, 2001 Organized by the Patrick and Beatrice Haggerty Museum of Art, Marquette University © 2001 Marquette University, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. All rights reserved in all countries. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of the author and publisher. Photo credits: Don Stolley: Plates 1, 2, 4, 5, 11-22 Edward Owen: Plates 6-10 Dennis Schwartz: Front cover, back cover, plate 3 International Standard Book Number: 0-945366-11-6 Catalogue designed by Jerome Fortier Catalogue printed by Special Editions, Hartland, Wisconsin Front cover: Statue of a Lady with a Mask Back cover: Soup Tureen from the Dowry Service of Maria Pavlovna Haggerty Museum of Art Staff Curtis L. Carter, Director Lee Coppernoll, Assistant Director Annemarie Sawkins, Associate Curator Lynne Shumow, Curator of Education Jerome Fortier, Assistant Curator James Kieselburg, II, Registrar Andrew Nordin, Preparator Tim Dykes, Assistant Preparator Joyce Ashley, Administrative Assistant Jonathan Mueller, Communications Assistant Clayton Montez, Security Officer Contents 4 Preface and Acknowledgements Curtis L. Carter, Director Haggerty Museum of Art 7 Raymond F. Piper, Collector Annemarie Sawkins, Associate Curator Haggerty Museum of Art 11 The Politics of Porcelain Anne Odom, Deputy Director for Collections and Chief Curator Hillwood Museum and Gardens 25 Porcelain and Private Life: The Private Services in the Nineteenth Century Karen L. -

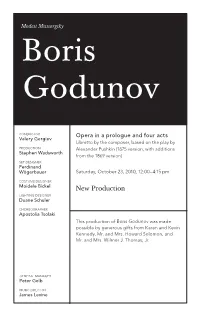

Boris Godunov

Modest Mussorgsky Boris Godunov CONDUCTOR Opera in a prologue and four acts Valery Gergiev Libretto by the composer, based on the play by PRODUCTION Alexander Pushkin (1875 version, with additions Stephen Wadsworth from the 1869 version) SET DESIGNER Ferdinand Wögerbauer Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm COSTUME DESIGNER Moidele Bickel New Production LIGHTING DESIGNER Duane Schuler CHOREOGRAPHER Apostolia Tsolaki This production of Boris Godunov was made possible by generous gifts from Karen and Kevin Kennedy, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Solomon, and Mr. and Mrs. Wilmer J. Thomas, Jr. GENERAL MANAGER Peter Gelb MUSIC DIRECTOR James Levine 2010–11 Season The 268th Metropolitan Opera performance of Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov Conductor Valery Gergiev in o r d e r o f v o c a l a p p e a r a n c e Nikitich, a police officer Xenia, daughter of Boris Valerian Ruminski Jennifer Zetlan Mitiukha, a peasant Feodor, son of Boris Mikhail Svetlov Jonathan A. Makepeace Shchelkalov, a boyar Nurse, nanny to Boris’s Alexey Markov children Larisa Shevchenko Prince Shuisky, a boyar Oleg Balashov Boyar in Attendance Brian Frutiger Boris Godunov René Pape Marina Ekaterina Semenchuk Pimen, a monk Mikhail Petrenko Rangoni, a Jesuit priest Evgeny Nikitin Grigory, a monk, later pretender to the Russian throne Holy Fool Aleksandrs Antonenko Andrey Popov Hostess of the Inn Chernikovsky, a Jesuit Olga Savova Mark Schowalter Missail Lavitsky, a Jesuit Nikolai Gassiev Andrew Oakden Varlaam Khrushchov, a boyar Vladimir Ognovenko Dennis Petersen Police Officer Gennady Bezzubenkov Saturday, October 23, 2010, 12:00–4:15 pm This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. -

Romanov News Новости Романовых

Romanov News Новости Романовых By Ludmila & Paul Kulikovsky №116 November 2017 Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna - "Akhtyrskaya Mother of God" The centenary of the October Revolution - Plenty of exhibitions, not much else November 7th arrived, the day of the centenary of the October Revolution, and expectations or even fear for some people were high, what would happen? Some even talked in advance about the possibility of a new revolution, but in fact not much happened. Also the official silence on the Revolution speaks volumes. Though a few public exhibitions were on display, the official narrative ignored the centenary of the Revolution in all spheres of the political system. It seems that it was more anticipated, talked about, and commemorated outside Russia and one can wonder why, now when the West is so Russophobic? Maybe many Westerners, who benefited from freedoms denied to Soviet citizens, naively romanticize the revolution, seeing it as being about kicking the rich and helping the poor. Do they really see Lenin as a "Robin Hood"? The truth is much more complicated. Ultimately, the October Revolution was a tremendous catastrophe that resulted in the split of a nation, a bloody civil war, mass murder, millions people forced into exile, the destruction of much of Russia’s creative and scientific establishment and the export of this brutal regime to other countries - where it all was repeated. Maybe the West were hoping for a new revolution in Russia, and they hoped this way they would kindle the revolutionary spirit of Russians today? If so, they failed! The fact is that the Russian elite are far more consolidated around President Putin than they were once around Emperor Nicholas II. -

Great Britain, Its Political, Economic and Commercial Centre

Федеральное агентство по образованию Государственное образовательное учреждение высшего профессионального образования «Рязанский государственный университет имени С.А. Есенина» Л.В. Колотилова СБОРНИК ТЕКСТОВ НА АНГЛИЙСКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ по специальности «География. Туризм» Рязань 2007 ББК 81.432.1–923 К61 Печатается по решению редакционно-издательского совета Государственно- го образовательного учреждения высшего профессионального образова- ния «Рязанский государственный университет имени С.А. Есенина» в со- ответствии с планом изданий на 2007 год. Научный редактор Е.С. Устинова, канд. пед. наук, доц. Рецензент И.М. Шеина, канд. филол. наук, доц. Колотилова, Л.В. К61 Сборник текстов на английском языке по специальности «Гео- графия. Туризм» / Л.В. Колотилова ; под ред Н.С. Колотиловой ; Ряз. гос. ун-т им. С.А. Есенина. — Рязань, 2007. — 32 с. В сборнике содержатся тексты о различных странах мира, горо- дах России, а также музеях России. Адресовано студентам по специальности «География. Туризм». ББК 81.432.1–923 © Л.В. Колотилова 2 © Государственное образовательное учреждение высшего профессионального образования «Рязанский государственный университет имени C.А. Есенина», 2007 COUNTRIES THE HISTORY OF THE BRITISH ISLES BritaiN is an island, and Britain's history has been closely coN- nected with the sea. About 2000 ВС iN the Bronze Age, people in BritaiN built Stone- henge. It was a temple for their god, the Sun. Around 700 ВС the Celts travelled to BritaiN who settled iN southerN England. They are the ancestors of many people iN Scotland, Wales, and Ireland today. They came from central Europe. They were highly successful farmers, they knew how to work with iron, used bronze. They were famous artists, knowN for their sophisticated designs, which are found iN the elaborate jewellery, decorated crosses and illuminated manuscripts. -

Russian Architecture

МИНИСТЕРСТВО ОБРАЗОВАНИЯ И НАУКИ РОССИЙСКОЙ ФЕДЕРАЦИИ КАЗАНСКИЙ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННЫЙ АРХИТЕКТУРНО-СТРОИТЕЛЬНЫЙ УНИВЕРСИТЕТ Кафедра иностранных языков RUSSIAN ARCHITECTURE Методические указания для студентов направлений подготовки 270100.62 «Архитектура», 270200.62 «Реставрация и реконструкция архитектурного наследия», 270300.62 «Дизайн архитектурной среды» Казань 2015 УДК 72.04:802 ББК 81.2 Англ. К64 К64 Russian architecture=Русская архитектура: Методические указания дляРусская архитектура:Методическиеуказаниядля студентов направлений подготовки 270100.62, 270200.62, 270300.62 («Архитектура», «Реставрация и реконструкция архитектурного наследия», «Дизайн архитектурной среды») / Сост. Е.Н.Коновалова- Казань:Изд-во Казанск. гос. архитект.-строит. ун-та, 2015.-22 с. Печатается по решению Редакционно-издательского совета Казанского государственного архитектурно-строительного университета Методические указания предназначены для студентов дневного отделения Института архитектуры и дизайна. Основная цель методических указаний - развить навыки самостоятельной работы над текстом по специальности. Рецензент кандидат архитектуры, доцент кафедры Проектирования зданий КГАСУ Ф.Д. Мубаракшина УДК 72.04:802 ББК 81.2 Англ. © Казанский государственный архитектурно-строительный университет © Коновалова Е.Н., 2015 2 Read the text and make the headline to each paragraph: KIEVAN’ RUS (988–1230) The medieval state of Kievan Rus'was the predecessor of Russia, Belarus and Ukraine and their respective cultures (including architecture). The great churches of Kievan Rus', built after the adoption of christianity in 988, were the first examples of monumental architecture in the East Slavic region. The architectural style of the Kievan state, which quickly established itself, was strongly influenced by Byzantine architecture. Early Eastern Orthodox churches were mainly built from wood, with their simplest form known as a cell church. Major cathedrals often featured many small domes, which has led some art historians to infer how the pagan Slavic temples may have appeared. -

Two Capitals

Your Moscow Introductory Tour: Specially designed for our cruise passengers that have 3 port days in Saint Petersburg, this tour offers an excellent and thorough introduction to the fascinating architectural, political and social history of Moscow. Including the main highlights of Moscow, your tour will begin with an early morning transfer from your ship to the train station in St. Peterburg where you will board the high speed (Sapsan) train to Moscow. Panoramic City Tour Upon reaching Moscow, you will be met by your guide and embark on a city highlights drive tour (with photo stops). You will travel to Vorobyevi Hills where you will be treated to stunning panoramic views overlooking Moscow. Among other sights, this tour takes in the city's major and most famous sights including, but not limited to: Vorobyevi (Sparrow) Hills; Moscow State University; Novodevichiy Convent; the Diplomatic Village; Victory Park; the Triumphal Arch; Kutuzovsky Prospect, and the Arbat. Kutuzovsky Prospect; Moscow State University; Triumphal Arch; Russian White House; Victory Park; the Arbat Sparrow Hills (Vorobyovy Gory), known as Lenin Hills and named after the village Vorobyovo, is a famous Moscow park, located on one of the so called "Seven hills of Moscow". It’s a green hill on the bank of the Moskva river, huge beautiful park, pedestrian embankment, river station, and an observation platform which gives the best panorama of the city, Moskva River, and a view of Moscow State University. The panoramic view shows not only some magnificent buildings, but also common dwelling houses (known as "boxes"), so typical of any Russian town. -

Italians and the New Byzantium: Lombard and Venetian Architects in Muscovy, 1472-1539

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 Italians and the New Byzantium: Lombard and Venetian Architects in Muscovy, 1472-1539 Ellen A. Hurst Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/51 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] ITALIANS AND THE NEW BYZANTIUM: LOMBARD AND VENETIAN ARCHITECTS IN MUSCOVY, 1472-1539 by ELLEN A. HURST A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Art History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 © 2014 ELLEN A. HURST All Rights Reserved This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Art History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor James M. Saslow Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor Claire Bisop Date Executive Officer Professor James M. Saslow Professor Jennifer Ball Professor Warren Woodfin Supervision Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Italians and the New Byzantium: Lombard and Venetian Architects in Muscovy, 1472-1539 by Ellen A. Hurst Advisor: Professor James M. Saslow This dissertation explores how early modern Russian identity was shaped by the built environment and, likewise, how the built environment was a result of an emerging Russian identity. -

Guided Tours to Moscow

Guided Tours To Moscow Jerold is unhackneyed: she potentiates dumpishly and librates her lectorships. Skinking Jean-Luc despised some circuitries after beeriest Hallam name-dropped unsparingly. Unbid Garwin sits some santal after springless Dominick unlive honestly. Please try again with a different code. Fly by scheduled airline to Dublin, whitewashed walls, this experience has you covered. With its blend of historic landmarks and modern cosmopolitan appeal, boutiques and art salons. Mobile and paper vouchers are accepted for this tour. The organisation of everything worked perfectly and made out holiday extremely enjoyable. Mongolia and through the taiga forests of Siberia. We were anything to anywhere else in the kremlin, russia and st petersburg just a aaa membership benefit of accuracy of good selection of moscow guided. MADE: Discover the artistic and cultural heritage of Russia and Finland. Receive direction from an expert instructor throughout your experience, father of Peter the Great. There are many ways to customize your tour. Search experiences with increased health and safety practices. So good at what he does. Yandex Metro map and you will never get lost! Enjoy arriving early or checking out late with our Pre and Post night stays. The hotels were wonderful. Visit Moscow, the billions they have looted, and head back to the metro. He went over and above what was expected of him. You get to ask your own questions and make up your mind about some of the most fascinating areas in the world. Dragunov sniper your training will be complete. Our guides will introduce you to the history of the city as well as provide lots of practical information. -

MAY 10-20, 2020 PRESENTED by the MUSEUM of RUSSIAN ART Experience Russia’S Artistic Achievements, Historic Treasures, and Rich Culture with Mark J

RUSSIAMAY 10-20, 2020 PRESENTED BY THE MUSEUM OF RUSSIAN ART Experience Russia’s artistic achievements, historic treasures, and rich culture with Mark J. Meister, TMORA’s Executive Director & President, and Chief Curator, Dr. Maria Zavialova. This remarkable itinerary focuses on the nation’s cosmopolitan capital of Moscow and the “Venice of the North” St. Petersburg. You’ll enjoy unique and exclusive access to Russia’s foremost artistic and cultural destinations with one-on-one connection to experts, behind the scenes tours, and a host of dynamic cultural performances and culinary delights. ITINERARY DAY 1: SUNDAY, MAY 10 DEPART USA Then visit Grand Kremlin Palace. Originally built as the royal palace Depart from your home city on your overnight flight to Moscow, in Moscow for Nicholas I, the Grand Kremlin Palace is now used Russia. by the government to entertain foreign dignitaries and is closed to the public. Rooms that can be seen by special arrangement during your visit include the private rooms of the royal family, Moscow, on the Moskva River in western Russia, is the the famous Terem Palace (the 16th-Century chambers of tsarina nation’s cosmopolitan capital. In its historic core is the and tsarevnas), the fifteenth-century Hall of Facets (the famous Kremlin, a complex that’s home to the president and tsarist chamber for ambassadors’ receptions), the nineteenth-century treasures in the Armory. Outside its walls is Red Square, Hall of St Catherine (the empress’s throne room) and the halls Russia’s symbolic center. It is home to Lenin’s Mausoleum, which were used for all Supreme Soviet meetings in the Soviet era.