Telecommunications Sector Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Case of Ukraine

LAPPEENRANTA UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY Northern Dimension Research Centre Publication 6 Tauno Tiusanen, Oksana Ivanova, Daria Podmetina EU’S NEW NEIGHBOURS: THE CASE OF UKRAINE Lappeenranta University of Technology Northern Dimension Research Centre P.O.Box 20, FIN-53851 Lappeenranta, Finland Telephone: +358-5-621 11 Telefax: +358-5-621 2644 URL: www.lut.fi/nordi Lappeenranta 2004 ISBN 951-764-896-0 (paperback) ISBN 951-764-897-9 (PDF) ISSN 1459-6679 EU’s New Neighbours: The Case of Ukraine Tauno Tiusanen Oksana Ivanova Daria Podmetina 1 Contents LIST OF TABLES 2 FOREWORD 4 1. INTRODUCTION 5 2. UKRAINIAN ECONOMIC TRENDS 2.1. Economic Growth and Stability in the Early Period of Transition 6 2.2. Investment and Productivity 9 2.3. Living Standard 11 2.4. Current Economic Trends 15 2.5. Distribution of Incomes and Household Expenditures 16 3. UKRAINE: HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY, ECONOMY AND POLITICS 3.1. Geographic Location, Climate and Natural Resources 20 3.2. Political System and Regions 22 3.3. History of Ukraine 24 3.4. Economic History and Reforms 26 4. INVESTMENT CLIMATE IN UKRAINE 4.1 Foreign Direct Investment in Ukraine 34 4.2. Motives and Obstacles for FDI in Ukraine 37 4.3. Ukraine in International Ratings 40 4.4. The Legal Framework for FDIs 43 4.5. Special Economic Zones 45 5. THE INVESTMENT RATING OF UKRAINIAN REGIONS 5.1. FDIs by Regions 49 5.2. The Investment Rating of Ukrainian Regions 50 5.3. Description of Ukrainian Regions 52 6. FDI SCENE IN UKRAINE: BUSINESS EXAMPLES 6.1. FDI Strategies 72 6.2. -

PROVISIONALLY APPROVED by the Board of Directors of OJSC Rostelecom May 19, 2014 Minutes No 01 Dated May 22, 2014

PROVISIONALLY APPROVED by the Board of Directors of OJSC Rostelecom May 19, 2014 Minutes No 01 dated May 22, 2014 APPROVED by the Annual General Shareholders’ Meeting of OJSC Rostelecom June 30, 2014 Minutes No___ dated June __, 2014 ANNUAL REPORT OPEN JOINT STOCK COMPANY LONG-DISTANCE AND INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS ROSTELECOM BASED ON YEAR 2013 RESULTS President of OJSC Rostelecom s/s S.B. Kalugin Acting Chief Accountant of OJSC Rostelecom s/s N.V. Lukashin May 22, 2014 Moscow, 2014 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS CAUTIONARY STATEMENT REGARDING FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS ....................................... 3 INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS ANNUAL REPORT .............................................................................. 4 ROSTELECOM AT A GLANCE ......................................................................................................................... 5 THE PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE ......................................................................................................................... 6 2013 HIGHLIGHTS ............................................................................................................................................ 8 OPERATING AND FINANCIAL RESULTS ...................................................................................................... 10 COMPANY’S POSITION IN THE INDUSTRY ................................................................................................. 12 COMPANIES IN ROSTELECOM GROUP ...................................................................................................... -

The Internet and Its Legal Ramifications in Taiwan

The Internet and its Legal Ramifications in Taiwan George C.C. Chen* INTRODUCTION The growth of the Internet over the last decade has been an astonishing phenomenon. Used by only a few academics in the late 1980s, it now has up to 65 million users worldwide.' Taiwan has followed the Internet trend eagerly, and already has approximately 500,000 users. Ever since United States Vice President, Albert Gore announced the U.S. National Information Infrastructure (Nil) project in Septem- ber 1993, many other countries have followed suit, initiating similar projects to establish a comprehensive information infrastructure. Many governments regard such development as a prerequisite for continuing national advancement in the 21 st century, and view success in this area as closely tied to the competitiveness of a nation's industry and the welfare of its people. In order to promote such a project, in June 1994, the Republic of China on Taiwan (hereinafter referred to as Taiwan) established an NII Special Project Committee2 (hereinafter referred to as the NII Committee) under the Executive Yuan.3 Under the NII Committee's direction, many activities are underway that are intended to serve as the foundation of Taiwan's development into a regional * Attorney-at-law; Director of Science & Technology Law Center (STLC), Institute for Information Industry in Taiwan; Secretary General of the Information Product Anti-Piracy Alliance of the Republic of China; Legal Member of the Private Sector Advisory Committee on National Information Infrastructure (NII) in Taiwan. STLC is Taiwan's only research organization fully focused on Internet and NII related legal issues. -

TV and On-Demand Audiovisual Services in Albania Table of Contents

TV and on-demand audiovisual services in Albania Table of Contents Description of the audiovisual market.......................................................................................... 2 Licensing authorities / Registers...................................................................................................2 Population and household equipment.......................................................................................... 2 TV channels available in the country........................................................................................... 3 TV channels established in the country..................................................................................... 10 On-demand audiovisual services available in the country......................................................... 14 On-demand audiovisual services established in the country..................................................... 15 Operators (all types of companies)............................................................................................ 15 Description of the audiovisual market The Albanian public service broadcaster, RTSH, operates a range of channels: TVSH (Shqiptar TV1) TVSH 2 (Shqiptar TV2) and TVSH Sat; and in addition a HD channel RTSH HD, and three thematic channels on music, sport and art. There are two major private operators, TV Klan and Top Channel (Top Media Group). The activity of private electronic media began without a legal framework in 1995, with the launch of the unlicensed channel Shijak TV. After -

Financial Analysis Summary Update 2021

FINANCIAL ANALYSIS SUMMARY UPDATE 2021 Prepared by Rizzo, Farrugia & Co (Stockbrokers) Ltd, in compliance with the Listing Policies issued by the Malta Financial Services Authority, dated 5 March 2013. 10 May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS IMPORTANT INFORMATION LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS PART A BUSINESS & MARKET OVERVIEW UPDATE PART B FINANCIAL ANALYSIS PART C LISTED SECURITIES PART D COMPARATIVES PART E GLOSSARY 1 | P a g e IMPORTANT INFORMATION PURPOSE OF THE DOCUMENT Cablenet Communication Systems plc (the “Company”, “Cablenet”, or “Issuer”) issued €40 million 4% bonds maturing in 2030 pursuant to a prospectus dated 21 July 2020 (the “Bond Issue”). In terms of the Listing Policies of the Listing Authority dated 5 March 2013, bond issues targeting the retail market with a minimum subscription level of less than €50,000 must include a Financial Analysis Summary (the “FAS”) which is to be updated on an annual basis. SOURCES OF INFORMATION The information that is presented has been collated from a number of sources, including the Company’s website (www.cablenet.com.cy), the audited financial statements for the years ended 31 December 2018, 2019 and 2020, and forecasts for financial year ending 31 December 2021. Forecasts that are included in this document have been prepared and approved for publication by the directors of the Company, who undertake full responsibility for the assumptions on which these forecasts are based. Wherever used, FYXXXX refers to financial year covering the period 1st January to 31st December. The financial information is being presented in thousands of Euro, unless otherwise stated, and has been rounded to the nearest thousand. -

NW ICT Cluster

Sarja B 199 Series ______________________________________________________ Andrey Averin – Grigory Dudarev BUSY LINES, HECTIC PROGRAMMING A Competitive Analysis of the Northwest Russian ICT Cluster ETLA, The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy Publisher: Taloustieto Oy Helsinki 2003 Cover: Mainos MayDay, Vantaa 2003 ISBN 951-628-381-0 ISSN 0356-7443 Printed in: Tummavuoren Kirjapaino Oy, Vantaa 2003 AVERIN, Andrey – DUDAREV, Grigory, BUSY LINES, HECTIC PROGRAM- MING: Competitive Analysis of the Northwest Russian ICT Cluster. Helsinki: ETLA, Elinkeinoelämän Tutkimuslaitos, The Research Institute of the Finnish Economy, 2003, 161 p. (B, ISSN 0356-7443; No. 199). ISBN 951-628-381-0. ABSTRACT: Northwest Russia and particularly St. Petersburg were a globally im- portant development center for information and communication technologies (ICT) during 1850-1950. The region’s position of strength deteriorated after this period as a consequence of the choices made about technology and Soviet secrecy. However, the region and its ICT industries still enjoy the benefits of education provision, the re- search-oriented tradition and inherited human and industrial capital. The transition to the market economy opened up many opportunities but also resulted in the evapora- tion of uncompetitive producers like giant electronics manufacturers. It also reduced financing and changed the priorities for R&D and education. At the same time, breakthroughs in telecom technologies and the overwhelming success of mobile communications greatly influenced the ICT industries in Russia. Understanding the major changes and trends is crucial for industrial policy and business strategy deci- sion makers. In this study, we identify the Northwest Russian ICT cluster and the key matters related to its competitiveness and growth prospects in the new environment. -

The Ict Research Environment in Montenegro

THE ICT RESEARCH ENVIRONMENT IN MONTENEGRO November 2008. Table of Contents ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 3 1. MONTENEGRIN ICT POLICY FRAMEWORK ................................................. 4 1.1. OVERALL ICT POLICY FRAMEWORK ......................................................... 4 1.2. THE ELEMENTS OF ICT RESEARCH POLICY MAKING ............................ 7 2. OVERVIEW OF ICT RESEARCH ACTIVITIES .............................................. 11 2.1. ICT RESEACH PROJECTS .............................................................................. 11 2.2. KEY COMPETENCIES IN ICT RESEARCH FIELDS ................................... 14 3. KEY DRIVERS OF ICT RESEARCH .................................................................. 15 3.1. MAIN ICT SECTOR TRENDS IN MONTENEGRO ....................................... 15 3.2. MAIN SOCIO-ECONOMIC CHALLENGES IN MONTENEGRO ................ 19 APPENDIX 1 - MAIN FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS ...................................... 21 2 Abstract This report is developed in November 2008 in the content WBC-INCO.NET project and is orientated along the lines of the SCORE reports-document that can serve to consulting expert ICT stakeholders about the relevant ICT research priorities in each WB country in the period 2007-2013. The report provides a brief overview of the ICT research environment in Montenegro. It includes key facts and figures concerning policy framework, current trends as well as short -

Turkcell the Digital Operator

Turkcell the Digital Operator Turkcell Annual Report 2018 About Turkcell Turkcell is a digital operator headquartered in Turkey, serving its customers with its unique portfolio of digital services along with voice, messaging, data and IPTV services on its mobile and fixed networks. Turkcell Group companies operate in 5 countries – Turkey, Ukraine, Belarus, Northern Cyprus, Germany. Turkcell launched LTE services in its home country on April 1st, 2016, employing LTE-Advanced and 3 carrier aggregation technologies in 81 cities. Turkcell offers up to 10 Gbps fiber internet speed with its FTTH services. Turkcell Group reported TRY 21.3 billion revenue in FY18 with total assets of TRY 42.8 billion as of December 31, 2018. It has been listed on the NYSE and the BIST since July 2000, and is the only NYSE-listed company in Turkey. Read more at www.turkcell.com.tr/english-support All financial results in this annual report are prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and expressed in Turkish Lira (TRY or TL) unless otherwise stated. TABLE OF CONTENTS TRY Turkcell Group 16 Chairman’s Message 21.3 20 Board of Directors 22 Message from the CEO billion 26 Executive Officers 28 Top Management of Subsidiaries REVENUES 30 Turkcell Group 31 Our Vision, Target, Strategy and Approach 32 2018 at a Glance 34 2018 Highlights 36 The World’s 1st Digital Operator Brand: Lifecell 37 Turkcell’s Digital Services 2018 Operations 38 Exemplary Digital Operator 40 Our Superior Technology 41.3% 46 Our Consumer Business EBITDA 52 Our -

Eutelsat S.A. €300,000,000 3.125% Bonds Due 2022 Issue Price: 99.148 Per Cent

EUTELSAT S.A. €300,000,000 3.125% BONDS DUE 2022 ISSUE PRICE: 99.148 PER CENT The €300,000,000 aggregate principal amount 3.125% per cent. bonds due 10 October 2022 (the Bonds) of Eutelsat S.A. (the Issuer) will be issued outside the Republic of France on 9 October 2012 (the Bond Issue). Each Bond will bear interest on its principal amount at a fixed rate of 3.125 percent. per annum from (and including) 9 October 2012 (the Issue Date) to (but excluding) 10 October 2022, payable in Euro annually in arrears on 10 October in each year and commencing on 10 October 2013, as further described in "Terms and Conditions of the Bonds - Interest"). Unless previously redeemed or purchased and cancelled in accordance with the terms and conditions of the Bonds, the Bonds will be redeemed at their principal amount on 10 October 2022 (the Maturity Date). The Issuer may at its option, and in certain circumstances shall, redeem all (but not part) of the Bonds at par plus any accrued and unpaid interest upon the occurrence of certain tax changes as further described in the section "Terms and Conditions of the Bonds - Redemption and Purchase - Redemption for tax reasons". The Bondholders may under certain conditions request the Issuer to redeem all or part of the Bonds following the occurrence of certain events triggering a downgrading of the Bonds as further described in the Section "Terms and Conditions of the Bonds — Redemption and Purchase - Redemption following a Change of Control". The obligations of the Issuer in respect of principal and interest payable under the Bonds constitute direct, unconditional, unsecured and unsubordinated obligations of the Issuer and shall at all times rank pari passu among themselves and pari passu with all other present or future direct, unconditional, unsecured and unsubordinated obligations of the Issuer, as further described in "Terms and Conditions of the Bonds - Status". -

ARCTIC BROADBAND Recommendations for an Interconnected Arctic

ARCTIC BROADBAND Recommendations for an Interconnected Arctic Telecommunications Infrastructure Working Group Table of Contents ` AEC Chair Messages . .2 Message from AEC chair, Tara Sweeney ` Executive Summary . .3 I am incredibly proud of the hard work and dedication demonstrated by the ` I . Introduction . .5 members of the Telecommunications Infrastructure Working group. The pan-Arctic engagement evident throughout this document exhibits the strong commitment of ` II . Key Issues . .6 the Arctic business community to support the Arctic Economic Council’s four core principles of partnership, collaboration, innovation and peace. ` III . The Current State of Broadband in the Arctic . .14 Being raised in rural Alaska, I have a deep understanding for the importance of ` IV . Funding Options . .19 connectivity and the challenges that come with a lack of reliable communications. ` V . Past, Current and Proposed Projects . 22. Expanding broadband access and adoption will be vital for the economic, social and political growth of local Arctic communities. It is my hope that these ` VI . Goals and Recommendations . .27 recommendations add value to the ongoing discussion of broadband deployment ` VII . Conclusion . 30. in the Arctic, and serve as a tool for policy makers, investors, researchers and communities to come together for sustainable polar growth. ` AEC Telecommunications Infrastructure Working Groups . 31. ` Citations . .37 Message from AEC Telecommunications Infrastructure Working Group chair, Robert McDowell The recommendations provided in this report are the result of a true collaborative effort among the business community within the eight Arctic states. Together, local Arctic residents and expert broadband advisors have combined their knowledge to establish a comprehensive strategy for the deployment and adoption of broadband in the far north – a first of its kind. -

Increasing Broadband Internet Penetration in the OIC Member Countries

Standing Committee for Economic and Commercial Cooperation of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (COMCEC) Increasing Broadband Internet Penetration In the OIC Member Countries COMCEC COORDINATION OFFICE February 2017 Standing Committee for Economic and Commercial Cooperation of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (COMCEC) Increasing Broadband Internet Penetration In the OIC Member Countries COMCEC COORDINATION OFFICE February 2017 This report has been commissioned by the COMCEC Coordination Office to Telecom Advisory Services, LLC. Views and opinions expressed in the report are solely those of the author(s) and do not represent the official views of the COMCEC Coordination Office or the Member States of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation. Excerpts from the report can be made as long as references are provided. All intellectual and industrial property rights for the report belong to the COMCEC Coordination Office. This report is for individual use and it shall not be used for commercial purposes. Except for purposes of individual use, this report shall not be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including printing, photocopying, CD recording, or by any physical or electronic reproduction system, or translated and provided to the access of any subscriber through electronic means for commercial purposes without the permission of the COMCEC Coordination Office. For further information please contact: COMCEC Coordination Office Necatibey Caddesi No: 110/A 06100 Yücetepe Ankara/TURKEY Phone: 90 312 294 57 10 Fax: 90 312 294 57 77 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.comcec.org Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 I. INTRODUCTION 8 II. CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK REGARDING bROADbAND PENETRATION 11 II.1. -

Ready for Upload GCD Wls Networks

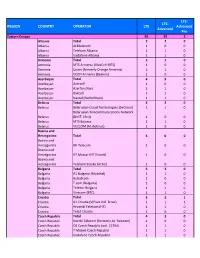

LTE‐ LTE‐ REGION COUNTRY OPERATOR LTE Advanced Advanced Pro Eastern Europe 92 55 2 Albania Total 320 Albania ALBtelecom 100 Albania Telekom Albania 110 Albania Vodafone Albania 110 Armenia Total 310 Armenia MTS Armenia (VivaCell‐MTS) 100 Armenia Ucom (formerly Orange Armenia) 110 Armenia VEON Armenia (Beeline) 100 Azerbaijan Total 430 Azerbaijan Azercell 100 Azerbaijan Azerfon (Nar) 110 Azerbaijan Bakcell 110 Azerbaijan Naxtel (Nakhchivan) 110 Belarus Total 420 Belarus Belarusian Cloud Technologies (beCloud) 110 Belarusian Telecommunications Network Belarus (BeST, life:)) 100 Belarus MTS Belarus 110 Belarus VELCOM (A1 Belarus) 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina Total 300 Bosnia and Herzegovina BH Telecom 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina HT Mostar (HT Eronet) 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina Telekom Srpske (m:tel) 100 Bulgaria Total 530 Bulgaria A1 Bulgaria (Mobiltel) 110 Bulgaria Bulsatcom 100 Bulgaria T.com (Bulgaria) 100 Bulgaria Telenor Bulgaria 110 Bulgaria Vivacom (BTC) 110 Croatia Total 321 Croatia A1 Croatia (VIPnet incl. B.net) 111 Croatia Hrvatski Telekom (HT) 110 Croatia Tele2 Croatia 100 Czech Republic Total 430 Czech Republic Nordic Telecom (formerly Air Telecom) 100 Czech Republic O2 Czech Republic (incl. CETIN) 110 Czech Republic T‐Mobile Czech Republic 110 Czech Republic Vodafone Czech Republic 110 Estonia Total 330 Estonia Elisa Eesti (incl. Starman) 110 Estonia Tele2 Eesti 110 Telia Eesti (formerly Eesti Telekom, EMT, Estonia Elion) 110 Georgia Total 630 Georgia A‐Mobile (Abkhazia) 100 Georgia Aquafon GSM (Abkhazia) 110 Georgia MagtiCom