Increasing Broadband Internet Penetration in the OIC Member Countries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Destinaton Code Destination Name Rate 63933 Philippines Mobile Sun 0.0865 63932 Philippines Mobile Sun 0.0865 63923 Philippines

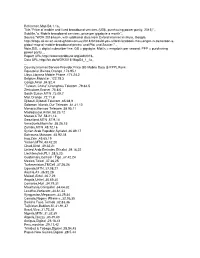

Destinaton Code Destination Name Rate 63933 Philippines Mobile Sun 0.0865 63932 Philippines Mobile Sun 0.0865 63923 Philippines Mobile Sun 0.0865 63922 Philippines Mobile Sun 0.0865 63925 Philippines Mobile Sun 0.0865 63931 Philippines Mobile Sun 0.0865 93 Afghanistan Fixed 0.17 9377 Afghanistan Mobile Areeba 0.095 9376 Afghanistan Mobile Areeba 0.095 9375 Afghanistan Mobile AT 0.0945 35568 Albania Mobile AMC 0.265 35567 Albania Mobile Eagle 0.292 50474124 Honduras Mobile Hondutel 0.098 50474123 Honduras Mobile Hondutel 0.098 63950 Philippines Mobile Smart 0.0855 6398 Philippines Mobile Smart 0.0855 63962 Philippines Mobile Smart 0.0855 63813 Philippines Mobile Smart 0.0855 21366 Algeria Mobile Mobilis 0.272 21369 Algeria Mobile Mobilis 0.272 213659 Algeria Mobile Mobilis 0.272 213658 Algeria Mobile Mobilis 0.25 21367 Algeria Mobile Mobilis 0.25 2135 Algeria Mobile Wataniya 0.275 21377 Algeria Mobile Orascom 0.174 21379 Algeria Mobile Orascom 0.174 21378 Algeria Mobile Orascom 0.174 25242 Somalia Fixed Golis 0.28 25255 Somalia Fixed Golis 0.28 25257 Somalia Fixed Golis 0.28 25258 Somalia Fixed Golis 0.28 25288 Somalia Fixed Golis 0.28 25290 Somalia Fixed Golis 0.28 25291 Somalia Fixed Golis 0.28 54 Argentina 0.019 5411 Argentina Buenos Aires 0.01 543543 Argentina Cities 0.01 54291 Argentina Cities 0.01 54348 Argentina Cities 0.01 543464 Argentina Cities 0.01 54351 Argentina Cities 0.01 543783 Argentina Cities 0.01 542362 Argentina Cities 0.01 542302 Argentina Cities 0.01 54221 Argentina Cities 0.01 54223 Argentina Cities 0.01 54261 Argentina -

Reference,Map B4.1.1A,, Title,"Price of Mobile and Fixed Broadband Services (US$, Purchasing Power Parity, 2015)",, Subtitle,"A

Reference,Map B4.1.1a,, Title,"Price of mobile and fixed broadband services (US$, purchasing power parity, 2015)",, Subtitle,"a. Mobile broadband services, price per gigabyte a month",, Source,"WDR 2016 team, with additional data from Oxford Internet Institute, Google, http://blogs.oii.ox.ac.uk/roughconsensus/2014/02/could-you-afford-facebook-messenger-in-cameroon-a- global-map-of-mobile-broadband-prices/ and Plot and Scatter.",, Note,DSL = digital subscriber line; GB = gigabyte; Mbit/s = megabits per second; PPP = purchasing power parity.,, Report URL,http://www.worldbank.org/wdr2016,, Data URL,http://bit.do/WDR2016-MapB4_1_1a,, ,,, Country,Internet Service Provider,Price GB Mobile Data ($ PPP),Rank Equatorial Guinea,Orange ,173.95,1 Libya,Libyana Mobile Phone ,171.24,2 Belgium,Mobistar ,122.78,3 Congo,Airtel ,94.52,4 "Taiwan, China",Chunghwa Telecom ,79.64,5 Zimbabwe,Econet ,76.8,6 South Sudan,MTN ,73.09,7 Mali,Orange ,72.11,8 Djibouti,Djibouti Telecom ,65.08,9 Solomon Islands,Our Telecom ,61.31,10 Monaco,Monaco Telecom ,58.95,11 Madagascar,Airtel ,58.23,12 Macao,CTM ,58.21,13 Swaziland,MTN ,57.9,14 Venezuela,Movistar ,55.26,15 Zambia,MTN ,48.72,16 Syrian Arab Republic,Syriatel ,46.89,17 Botswana,Mascom ,45.92,18 Iraq,Zain ,45.65,19 Yemen,MTN ,43.42,20 Chad,Airtel ,39.32,21 United Arab Emirates,Etisalat ,39.16,22 Liechtenstein,FL1 ,38.5,23 Guatemala,Comcel / Tigo ,37.42,24 Mexico,Telcel ,37.36,25 Turkmenistan,TMCell ,37.26,26 Uganda,MTN ,37.08,27 Austria,A1 ,36.92,28 Malawi,Airtel ,36.7,29 Angola,Unitel ,36.69,30 Comoros,Huri ,34.79,31 -

Turkcell Annual Report 2010

TURKCELL ANNUAL REPORT 2010 GET MoRE oUT of LIfE WITh TURKCELL CoNTENTS PAGE our Vision / our Values / our Strategic Priorities 4 Turkcell Group in Numbers 6 Turkcell: Leading Communication and Technology Company 8 Letter from the Chairman 10 Board Members 12 Letter from the CEo 14 Executive officers 16 Superior Technologies 22 More Advantages 32 Best Quality Service 40 More Social Responsibility 46 Awards 53 Managers of Turkcell Affiliates 54 Subsidiaries 56 human Resources 62 Mobile Telecommunication Sector 66 International Ratings 72 Investor Relations 74 Corporate Governance 78 Turkcell offices 95 Consolidated financial Statement and Independent Audit Report 96 Dematerialization of The Share Certificates of The Companies That Are Traded on The Stock Exchange 204 The Board’s Dividend Distribution Proposal 205 2 3 oUR VISIoN oUR STRATEGIC PRIoRITIES To ease and enrich the lives of our customers with communication and As a Leading Communication and Technology Company, technology solutions. • to grow in our core mobile communication business through increased use of voice and data, • to grow our existing international subsidiaries with a focus on profitability, oUR VALUES • to grow in the fixed broadband business by creating synergy among Turkcell Group companies through our fiber optic infrastructure, • We believe that customers come first • to grow in the area of mobility, internet and convergence through new • We are an agile team business opportunities, • We promote open communication • to grow in domestic and international markets through communications, • We are passionate about making a difference technology and new business opportunities, • We value people • to develop new service platforms that will enrich our relationship with our customers through our technical capabilities. -

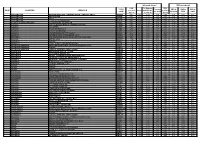

ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR TADIG CODE Calls

Calls made abroad SMS sent abroad Calls To Belgium SMS TADIG To zones SMS to SMS to SMS to ZONE COUNTRIES OPERATOR received Local and Europe received CODE 2,3 and 4 Belgium EUR ROW abroad (= zone1) abroad 3 AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS COMMUNICATION COMPANY 'AWCC' AFGAW 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN AREEBA MTN AFGAR 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN TDCA AFGTD 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 3 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT AFGHANISTAN AFGEA 0,91 0,99 2,27 2,89 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 1 ALANDS ISLANDS (FINLAND) ALANDS MOBILTELEFON AB FINAM 0,08 0,29 0,29 2,07 0,00 0,09 0,09 0,54 2 ALBANIA AMC (ALBANIAN MOBILE COMMUNICATIONS) ALBAM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA VODAFONE ALBVF 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALBANIA EAGLE MOBILE SH.A ALBEM 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA DJEZZY (ORASCOM) DZAOT 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA ATM (MOBILIS) (EX-PTT Algeria) DZAA1 0,74 0,91 1,65 2,27 0,00 0,41 0,62 0,62 2 ALGERIA WATANIYA TELECOM ALGERIE S.P.A. -

MAROC TELECOM GROUP a Significant Force in the Economic and Social Development in 11 African Countries

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE MANAGEMENT BOARD Abdeslam AHIZOUNE Chairman of the Management Board Hassan Brahim François Abdelkader RACHAD BOUDAOUD VITTE MAAMAR Managing Director Managing Director of Managing Director of Regulation Networks and Systems Chief Financial Officer of Services and Legal Affairs MAROC TELECOM ALSO INCLUDES REGIONAL DIVISIONS REPORTING8 TO THE CHAIRMAN OF THE MANAGEMENT BOARD. SUPERVISORY BOARD PRESIDENT MEMBRES Mohamed BENCHAABOUN Abdelouafi LAFTIT Minister of Economy, Finance and Minister of the Interior Administration Reform Abderrahmane SEMMAR Director of Public Companies and Privatization VICE-PRESIDENT at the Minister of Economy, Finance and Administration Reform Obaid Bin Humaid AL TAYER Mohamed Hadi AL HUSSAINI Chairman of Emirates Chairman of Emirates Integrated Telecommunications Company Telecommunications Corporation (Etisalat) Saleh AL ABDOOLI General Manager of Etisalat Group Mohammed Saif AL SUWAIDI General Manager of Abu Dhabi Fund for Development Hatem DOWIDAR Managing Director of Etisalat International MAROC TELECOM GROUP A significant force in the economic and social development in 11 African countries Maroc Telecom Group, a leading operator and leader in several countries, is present in 11 countries on the African continent : Morocco, Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Central African Republic, Chad and Togo. The Group supports more than 68 million Mobile, Fixed-line and Internet customers. Through its commitment to bridging the digital divide, the Group contributes significantly to economic and social development, access to NICTs and the well-being of populations both in Morocco and in all the countries of its subsidiaries. The Group's presence in Africa fits perfectly into the South-South cooperation policy, initiated by His Majesty King Mohammed VI. -

Kazakhtelecom – Leading Telecom Operator in Kazakhstan April 2019

Kazakhtelecom – leading telecom operator in Kazakhstan April 2019 1 Important Notice The information contained in this document (the ‘Corporate Presentation’) has been prepared by Kazakhtelecom JSC (‘Kazakhtelecom’, ‘KT’). Kazakhtelecom is a Kazakh incorporated and registered company listed on the Kazakhstan Stock Exchange (‘KASE’). This corporate presentation has not been fully verified and is subject to material updating, revision and further verification and amendment without notice. While the information contained herein has been prepared in good faith, neither Kazakhtelecom nor any of its directors, officers, shareholders, agents, employees or advisers give, have given or have authority to give, any representations or warranties (express or implied) as to, or in relation to, the accuracy, reliability or completeness of the information in this Corporate Presentation, or any revision thereof, or of any other written or oral information made or to be made available to any interested party or its advisers (all such information being referred to as ‘Information’) and liability therefore is expressly disclaimed. Accordingly, neither Kazakhtelecom nor any of its directors, officers, shareholders, agents, employees or advisers take any responsibility for, or will accept any liability whether direct or indirect, express or implied, contractual, tortious, statutory or otherwise, in respect of, the accuracy or completeness of the Information or for any of the opinions contained herein or for any errors, omissions or misstatements or for any loss, howsoever arising, from the use of this Corporate Presentation. The views of Kazakhtelecom’s management/directors/shareholders set out in this Corporate Presentation could ultimately prove to be incorrect. No warranty, express or implied, is given by the presentation of these figures and investors should place no reliance on Kazakhtelecom’s estimates cited, in this Corporate Presentation. -

Turkcell the Digital Operator

Turkcell the Digital Operator Turkcell Annual Report 2018 About Turkcell Turkcell is a digital operator headquartered in Turkey, serving its customers with its unique portfolio of digital services along with voice, messaging, data and IPTV services on its mobile and fixed networks. Turkcell Group companies operate in 5 countries – Turkey, Ukraine, Belarus, Northern Cyprus, Germany. Turkcell launched LTE services in its home country on April 1st, 2016, employing LTE-Advanced and 3 carrier aggregation technologies in 81 cities. Turkcell offers up to 10 Gbps fiber internet speed with its FTTH services. Turkcell Group reported TRY 21.3 billion revenue in FY18 with total assets of TRY 42.8 billion as of December 31, 2018. It has been listed on the NYSE and the BIST since July 2000, and is the only NYSE-listed company in Turkey. Read more at www.turkcell.com.tr/english-support All financial results in this annual report are prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) and expressed in Turkish Lira (TRY or TL) unless otherwise stated. TABLE OF CONTENTS TRY Turkcell Group 16 Chairman’s Message 21.3 20 Board of Directors 22 Message from the CEO billion 26 Executive Officers 28 Top Management of Subsidiaries REVENUES 30 Turkcell Group 31 Our Vision, Target, Strategy and Approach 32 2018 at a Glance 34 2018 Highlights 36 The World’s 1st Digital Operator Brand: Lifecell 37 Turkcell’s Digital Services 2018 Operations 38 Exemplary Digital Operator 40 Our Superior Technology 41.3% 46 Our Consumer Business EBITDA 52 Our -

Short Selling – Allowed (100% of Securities for Sell Orders and Repo Open Orders) • Securities Lending – Repo with Netting

Kazakhstan securities market: migration to T+2 settlement cycle Presenter: Idel SABITOV, Deputy CEO KASE 10 September 2015 XII International Conference ACDE Almaty • Shares market: statistics • KASE Index – Kazakhstan's shares market's business card • T+2: goals • Т+2: recommendations and standards • Transition from T+0 to T+2: timeline • T+2: main conditions • T+2: prefunding requirements and risk management elements • T+0: flowchart • T+2: flowchart • From T+0 to T+2 2 Shares market: statistics Traded Volume, bn USD Market Capitalization, bn USD Primary market (IPO) Secondary market 120 100 1.5 80 3.9 bn USD 48.7 bn USD as of 01.09.15 60 as of 01.01.05 40 2.8 Volume, bn USD 1.7 20 0.4 1.1 0.4 0.7 0.7 0.9 0.3 0 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.2 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015'8M Issuers by Industry Sectors Equities Market Energy Financials 102 103 108 99 92 95 100 7.9% 78 81 79 78 74 66 68 Provision of telecommunications Materials 11.4% 34.7% services Industrials Consumer staples 10.7% Provision of municipal services Information Technology 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 Health Care Consumer Discretionary (September) 31.5% Issuers Instruments 3 Shares market: statistics 100 Members of securities market 90 Volume of shares trading (as of 01.09.2015) (for 8 months 2015) 80 70 60 5 1 11% 50 40 48 492 30 17 participants 25 mln USD 20 10 89% 0 Shares 1st Shares 2nd category category Number of shares National Bank Brokers: banks KASE Index shares Non-Index shares Brokers: asset managers Other Total -

Download Speeds

Volume 08, September, 2017 A SAMENA Telecommunications Council Newsletter www.samenacouncil.org SAMENA TRENDS EXCLUSIVELY FOR SAMENA TELECOMMUNICATIONS COUNCIL'S MEMBERS BUILDING DIGITAL ECONOMIES Unleashing the Power of Digital Health 54 Building an Open and Diverse Ecosystem for Shared Success... 34 Exclusive Interview Eng. Saleh Al Abdooli Chief Executive Officer Etisalat Group DRIVING THE DIGITAL FUTURE VOLUME 08, SEPTEMBER, 2017 Contributing Editors Subscriptions Izhar Ahmad [email protected] Javaid Akhtar Malik Advertising SAMENA Contributing Members [email protected] Etisalat TRENDS Nokia SAMENA TRENDS Strategy& [email protected] Editor-in-Chief Tel: +971.4.364.2700 Bocar A. BA Publisher SAMENA Telecommunications Council CONTENTS 04 EDITORIAL 67 TECHNOLOGY UPDATES Technology News 18 REGIONAL & MEMBERS 78 REGULATORY & POLICY UPDATES Members News UPDATES Regulatory News Regional News A Snapshot of Regulatory Activities in the SAMENA 45 SATELLITE UPDATES Region Satellite News Regulatory Activities Beyond 58 WHOLESALE UPDATES the SAMENA Region The SAMENA TRENDS newsletter is Wholesale News wholly owned and operated by The SAMENA Telecommunications Council (SAMENA Council). Information in the newsletter is not intended as professional services advice, and SAMENA Council disclaims any liability for use of specific information or results thereof. Articles and information contained in this publication are the copyright of SAMENA Telecommunications Council, (unless otherwise noted, described or stated) and cannot be reproduced, copied or printed in any form without the express written permission of the publisher. The SAMENA Council does not necessari- 11 06 ly endorse, support, sanction, encourage, SAMENA COUNCIL ACTIVITY EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW verify or agree with the content, com- SAMENA Council Reflects on Public ments, opinions or statements made in Eng. -

Ready for Upload GCD Wls Networks

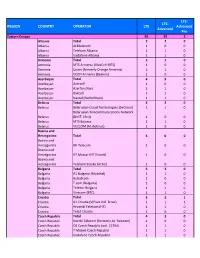

LTE‐ LTE‐ REGION COUNTRY OPERATOR LTE Advanced Advanced Pro Eastern Europe 92 55 2 Albania Total 320 Albania ALBtelecom 100 Albania Telekom Albania 110 Albania Vodafone Albania 110 Armenia Total 310 Armenia MTS Armenia (VivaCell‐MTS) 100 Armenia Ucom (formerly Orange Armenia) 110 Armenia VEON Armenia (Beeline) 100 Azerbaijan Total 430 Azerbaijan Azercell 100 Azerbaijan Azerfon (Nar) 110 Azerbaijan Bakcell 110 Azerbaijan Naxtel (Nakhchivan) 110 Belarus Total 420 Belarus Belarusian Cloud Technologies (beCloud) 110 Belarusian Telecommunications Network Belarus (BeST, life:)) 100 Belarus MTS Belarus 110 Belarus VELCOM (A1 Belarus) 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina Total 300 Bosnia and Herzegovina BH Telecom 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina HT Mostar (HT Eronet) 100 Bosnia and Herzegovina Telekom Srpske (m:tel) 100 Bulgaria Total 530 Bulgaria A1 Bulgaria (Mobiltel) 110 Bulgaria Bulsatcom 100 Bulgaria T.com (Bulgaria) 100 Bulgaria Telenor Bulgaria 110 Bulgaria Vivacom (BTC) 110 Croatia Total 321 Croatia A1 Croatia (VIPnet incl. B.net) 111 Croatia Hrvatski Telekom (HT) 110 Croatia Tele2 Croatia 100 Czech Republic Total 430 Czech Republic Nordic Telecom (formerly Air Telecom) 100 Czech Republic O2 Czech Republic (incl. CETIN) 110 Czech Republic T‐Mobile Czech Republic 110 Czech Republic Vodafone Czech Republic 110 Estonia Total 330 Estonia Elisa Eesti (incl. Starman) 110 Estonia Tele2 Eesti 110 Telia Eesti (formerly Eesti Telekom, EMT, Estonia Elion) 110 Georgia Total 630 Georgia A‐Mobile (Abkhazia) 100 Georgia Aquafon GSM (Abkhazia) 110 Georgia MagtiCom -

Annual Report 2019 a World Without Limits

A WORLD WITHOUT LIMITS ANNUAL REPORT 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 01. Key Highlights of 2019 05 15. Saudi Arabia 49 02. Business Snapshot 07 16. Egypt 51 03. Chairman’s Statement 08 17. Morocco 53 04. Board of Directors 10 18. Pakistan 57 05. Etisalat’s Journey 14 19. Afghanistan 60 06. Group CEO’s Statement 16 14. E-Vision 61 07. Management Team 18 20. Etisalat Services Holding 62 08. Vision and Strategy 22 21. Human Capital 65 09. Key Events During 2019 29 22. Corporate Social Responsibility 69 10. Operational Highlights 30 23. Corporate Governance 73 11. Brand Highlights 34 24. Enterprise Risk Management 76 12. Etisalat Group’s Footprint 40 25. Financials 81 13. United Arab Emirates 43 26. Notice for General Assembly Meeting 170 3 KEY HIGHLIGHTS OF 2019 EBITDA NET PROFIT REVENUE (BILLION) (BILLION) (BILLION) 52.2 26.4 8.7 AED AED AED CAPEX AGGREGATE DIVIDEND PER (BILLION) SUBSCRIBERS (MILLION) SHARE 80 8.9 149 FILS AED ANNUAL REPORT 2019 4 5 ETISALAT GROUP BUSINESS SNAPSHOT Etisalat Group offers a range of communication services to consum- speed on its 5G standalone network, Etisalat enabled 5G networks ers, businesses, and government segments in multiple regions. Our across several key sites in the UAE. As part of Maroc Telecom’s inter- portfolio of products and services include mobile, fixed broadband, national development strategy and plan to consolidate the group’s TV, voice, carrier services, cloud and security, internet of things, mo- presence in Africa, Maroc Telecom completed the acquisition of Tigo bile money, and other value added services. -

Network List Addendum

Network List Addendum IN-SITU PROVIDED SIM CELLULAR NETWORK COVERAGE COUNTRY NETWORK 2G 3G LTE-M NB-IOT COUNTRY NETWORK 2G 3G LTE-M NB-IOT (VULINK, (TUBE, (VULINK) (VULINK) TUBE, WEBCOMM) (VULINK, (TUBE, (VULINK) (VULINK) WEBCOMM) TUBE, WEBCOMM) WEBCOMM) Benin Moov X X Afghanistan TDCA (Roshan) X X Bermuda ONE X X Afghanistan MTN X X Bolivia Viva X X Afghanistan Etisalat X X Bolivia Tigo X X Albania Vodafone X X X Bonaire / Sint Eustatius / Saba Albania Eagle Mobile X X / Curacao / Saint Digicel X X Algeria ATM Mobilis X X X Martin (French part) Algeria Ooredoo X X Bonaire / Sint Mobiland Andorra X X Eustatius / Saba (Andorra) / Curacao / Saint TelCell SX X Angola Unitel X X Martin (French part) Anguilla FLOW X X Bosnia and BH Mobile X X Anguilla Digicel X Herzegovina Antigua and Bosnia and FLOW X X HT-ERONET X X Barbuda Herzegovina Antigua and Bosnia and Digicel X mtel X Barbuda Herzegovina Argentina Claro X X Botswana MTN X X Argentina Personal X X Botswana Orange X X Argentina Movistar X X Brazil TIM X X Armenia Beeline X X Brazil Vivo X X X X Armenia Ucom X X Brazil Claro X X X Aruba Digicel X X British Virgin FLOW X X Islands Australia Optus X CCT - Carribean Australia Telstra X X British Virgin Cellular X X Islands Australia Vodafone X X Telephone Austria A1 X X Brunei UNN X X Darussalam Austria T-Mobile X X X Bulgaria A1 X X X X Austria H3G X X Bulgaria Telenor X X Azerbaijan Azercell X X Bulgaria Vivacom X X Azerbaijan Bakcell X X Burkina Faso Orange X X Bahamas BTC X X Burundi Smart Mobile X X Bahamas Aliv X Cabo Verde CVMOVEL