Through the Shedding of Blood: a Comparison of the Levitical and the Supyire Concepts of Sacrifice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nature Redacted September 7,2017 Certified By

The Universality of Concord by Isa Kerem Bayirli BA, Middle East Technical University (2010) MA, Bogazigi University (2012) Submitted to the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY September 2017 2017 Isa Kerem Bayirli. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature redacted Author......................... ...... ............................. Departmeyf)/Linguistics and Philosophy Sic ;nature redacted September 7,2017 Certified by...... David Pesetsky Ferrari P. Ward Professor of Linguistics g nThesis Supervisor redacted Accepted by.................. Signature ...................................... David Pesetsky Lead, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEP 2 6 2017 LIBRARIES ARCHiVES The Universality of Concord by Isa Kerem Bayirh Submitted to the Deparment of Linguistics and Philosophy on September 7, 2017 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics Abstract In this dissertation, we develop and defend a universal theory of concord (i.e. feature sharing between a head noun and the modifying adjectives). When adjectives in a language show concord with the noun they modify, concord morphology usually involves the full set of features of that noun (e.g. gender, number and case). However, there are also languages in which concord targets only a subset of morphosyntactic features of the head noun. We first observe that feature combinations that enter into concord in such languages are not random. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Anii in Benin Dendi, Dandawa in Benin Population: 47,000 Population: 274,000 World Popl: 66,000 World Popl: 414,700 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: Guinean People Cluster: Songhai Main Language: Anii Main Language: Dendi Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 1.00% Evangelicals: 0.03% Chr Adherents: 2.00% Chr Adherents: 0.07% Scripture: Unspecified Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Kerry Olson Source: Jacques Taberlet "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Foodo in Benin Fulani, Gorgal in Benin Population: 45,000 Population: 43,000 World Popl: 46,100 World Popl: 43,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: Guinean People Cluster: Fulani / Fulbe Main Language: Foodo Main Language: Fulfulde, Western Niger Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Unreached Evangelicals: 0.01% Evangelicals: 0.00% Chr Adherents: 0.02% Chr Adherents: 0.00% Scripture: Portions Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Bethany World Prayer Center Source: Bethany World Prayer Center "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Fulfulde, Borgu in Benin Gbe, Seto in Benin Population: 650,000 Population: 40,000 World Popl: 767,700 World -

Supplementary Material for Linguistic Situation in Twenty Sub-Saharan African Countries: a Survey-Based Approach

Supplementary material for Linguistic situation in twenty Sub-Saharan African countries: a survey-based approach Katalin Buzasi (word count: 9942) 1 Introduction The aim of this supplementary material is to present available data on indigenous and European languages in the twenty sample countries and to compare them with the Afrobarometer (hereafter AB). The linguistic situation of each country is described in a table. Reported values are understood as percentages. Column 1 lists the name of groups as used and spelled in the AB codebook. The classification and the names of ethnic and linguistic groups in Q79 and Q3 are usually identical. Exceptions, if exist, are explained in the General notes under the tables. Column 2 and 3 show the share of the listed ethnic and linguistic groups based on Q79 (on ethnicity) and Q3 (on home language), respectively. Column 4 presents the share of the population speaking the listed languages as additional languages from Q88E. The total share of speakers is computed in Column 5. In order to cross-check the Afrobarometer data, the remaining columns (Column 6 to 11) present linguistic information from Ethnologue (Lewis et al. 2014), the latest available national censuses, and other sources. However, census questionnaires are not standardised across countries: certain countries collect information on ethnicity, while others on home languages or both. The column headings make it clear which one of the two is reported. The General notes have two additional aims. First, they list some references which contain information on the historical origins of the language situation, the spread of languages and their use in various domains (education, media etc.) and the design of language policies. -

Languages Avec Territoire Propre Au Mali 17 Mai 2006 Par Lee Hochstetler (SIL) Police Utilise'e: RCI Std Doulos = Rcidolr.Ttf

Languages avec Territoire Propre au Mali 17 mai 2006 par Lee Hochstetler (SIL) Police utilise'e: RCI Std Doulos = rcidolr.ttf BF= Burkina Faso, RCI = Ivory Coast, GH=Ghana, Gui =Guinea, GuB = Guinea Bisau, SL = Sierra Leone, Sen= Senegal, M=Mauritania, Alg =Algeria, Nig =Niger Glossonym <langue> Code Ethnologue Autre pays Nom alternatif et par qui dialectes majeurs Commentaires Hasanya Arabic [MEY] M, Sen. Appelle' hasanya arabic par SIL Mali. Appelle hasanya par gouvt malien. Appelle maure-orthographe franchise du gouvt malien. Appelld suraka par bambaraphones. Appelle suraxe par les soninke. Bamako Sign Lg. [BOG] Mali seul C.E.C.I., B.P. 109, Bamako Not related to other sign languages. Another community of deaf people in Bamako use a West African variety of American Sign Language. Bamanan<kan> [BAM] RCI, BF Appelle bamanankan par gouvt malien. Appelle bambara-orthographe franchise par gouvt malien et par bcp d'europeens. Dialectes:Bamako, Somono, Segou, San, Beledugu, Ganadugu, Wasulu, Sikasso. Banka<gooma> [BXW] Mali seul Appelle samogho par des gen£ralistes diachroniques. Parle a l'ouest de Danderesso (au nord de Sikasso). Kona<bere> [BBO] BF Appelle northern bobo madare par SIL BF. Appelle' black bobo [perj] par certains anglophones. Appelle' bobo-fin [perj] par certains bambaraphones. Appelle bobo par ceux qui generalize trop (il y a 2 varietes au BF). Ne le confondez pas avec le bomu. Bomu ou Bore [BMQ] BF Appelle bobo par gouvt malien. Boomu—un ancien orthographe du gouvt malien. Appelle' bobo oule [pej] par certains bambaraphones. Langues Maliennes.rtf Page 05/18/06 2 Appelle' red bobo [pej] par certains anglephones. -

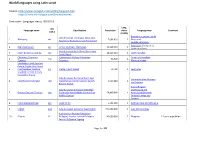

World Languages Using Latin Script

World languages using Latin script Source: http://www.omniglot.com/writing/langalph.htm https://www.ethnologue.com/browse/names Sort order : Language status, ISO 639-3 Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Botswana, Lesotho, South Indo-European, Germanic, West, Low 1. Afrikaans, afr 7,096,810 1 Africa and Saxon-Low Franconian, Low Franconian SwazilandNamibia Azerbaijan,Georgia,Iraq 2. Azeri,Azerbaijani azj Turkic, Southern, Azerbaijani 24,226,940 1 Jordan and Syria Indo-European Balto-Slavic Slavic West 3. Czech Bohemian Cestina ces 10,619,340 1 Czech Republic Czech-Slovak Chamorro,Chamorru Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian Guam and Northern 4. cha 94,700 1 Tjamoro Chamorro Mariana Islands Seychelles Creole,Seselwa Creole, Creole, Ilois, Kreol, 5. Kreol Seselwa, Seselwa, crs Creole, French based 72,700 1 Seychelles Seychelles Creole French, Seychellois Creole Indo-European Germanic North East Denmark Finland Norway 6. DanishDansk Rigsdansk dan Scandinavian Danish-Swedish Danish- 5,520,860 1 and Sweden Riksmal Danish AustriaBelgium Indo-European Germanic West High Luxembourg and 7. German Deutsch Tedesco deu German German Middle German East 69,800,000 1 NetherlandsDenmark Middle German Finland Norway and Sweden 8. Estonianestieesti keel ekk Uralic Finnic 1,132,500 1 Estonia Latvia and Lithuania 9. English eng Indo-European Germanic West English 341,000,000 1 over 140 countries Austronesian Malayo-Polynesian 10. Filipino fil Philippine Greater Central Philippine 45,000,000 1 Filippines L2 users population Central Philippine Tagalog Page 1 of 48 World languages using Latin script Lang, ISO Language name Classification Population status Language map Comment 639-3 (EGIDS) Denmark Finland Norway 11. -

OCP Effects in Dagaare*

OCP effects in Dagaare* Abstract In tone languages, adjacent high tones are often avoided. Different languages resolve the problem in different ways, but different resolutions can be found even in one and the same language. Dagaare (Gur, Niger-Congo) exhibits four different responses to a sequence of high tones: the second tone dissimilates, the second tone is downstepped, the two tones merge, or adjacent high tones are simply tolerated. The choice is morphologically and lexically conditioned. We present evidence that adjacent high tones are resolved only if they belong to the same tonal foot. We account for the different resolution patterns by assuming that morphemes may specify partial rankings: the tone of the complex word is the concatenation of the tones of its constituent morphemes, evaluated by the union of their partial rankings. * [Acknowledgements suppressed.] The following abbreviations are used: 3.SG ‘third person singular’, A ‘adjective’, COMP ‘complementiser’, DEF ‘definite article’, DEM ‘demonstrative’, FACT ‘factitive marker’, IMPF ‘imperfective aspect’, N ‘noun’, NOM ‘nominalization’, PERF ‘perfective aspect’, PL ‘plural’, SG ‘singular’. 1 1 Introduction In tone languages, adjacent high tones are often avoided. For example, Myers (1997) notes that different Bantu languages resolve HH sequences in different ways and different resolutions can be found even in one and the same language. One of the tones can be deleted or retracted from the other (Shona, Rimi, Chichewa); the tones can merge into a single high tone (Shona, Kishambaa); processes that would create such sequences are blocked (Shona); and sometimes adjacent high tones are simply tolerated (Kishambaa). Myers shows how all these outcomes can be derived from the OBLIGATORY CONTOUR PRINCIPLE (OCP, Goldsmith 1976, Leben 1973) which prohibits adjacent identical elements, but crucially only if the OCP is interpreted as a violable constraint in the sense of Optimality Theory (Prince & Smolensky 1993/2004). -

Question Formation in Efutu by Eugenia Serwaah Cobbina

University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh QUESTION FORMATION IN EFUTU BY EUGENIA SERWAAH COBBINA (10166154) THIS THESIS IS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF GHANA, LEGON, IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF M.PHIL LINGUISTICS DEGREE. JUNE, 2013 University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh i DECLARATION I declare that except for references to works which have been duly acknowledged, this dissertation is a result of my original research has neither in whole nor in part been submitted for another degree elsewhere. CANDIDATE ……………………………………… …………….… EUGENIA SERWAAH COBBINA DATE SUPERVISORS ……………………… …………….… PROF. KOFI K. SAAH DATE …………………………… ….…………… PROF. NANA ABA A. AMFO DATE University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Daniel Paa Wusu Cobbina and Agnes Adwoa Pokua Cobbina Parents who strive for their children to see further than they have, Who sacrifice their dreams so that their children can have one. University of Ghana http://ugspace.ug.edu.gh iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT To God be the glory for His loving kindness and tender mercies. If I have seen further, it is by standing on ye shoulders of giants - Isaac Newton. My sincerest thanks go to my ever patient supervisors Prof. Kofi K. Saah and Prof. Nana Aba A. Amfo, for your pieces of advice, corrections and invaluable suggestions; I say, may God show you favour, for without you, this work would not have been. Also to the head of department, Prof. Kofi Agyekum and the lecturers of the Linguistics Department, Legon, Prof. Alan Duthie, Prof. Akosua Anyidoho, Dr. -

The Levirate Custom of Inheriting Widows Among the Supyire People of Mali: Theological Pointers for Christian Marriage’

‘The Levirate Custom of Inheriting Widows among the Supyire People of Mali: Theological pointers for Christian marriage’ Michael William Thomas Jemphrey OCMS, Ph.D. November 2011 ABSTRACT The Supyire people of Mali practise levirate: when a woman is married, she permanently joins her husband’s family, and the marriage is not terminated by his death. Rather, it continues, with one of the husband’s younger brothers or cousins inheriting her and acting as a substitute levirate husband. The thesis describes how levirate is an integral part of the Supyire institution of marriage, how it gives marriage permanence, supporting the social structure, linking descent groups, determining access to land and providing a milieu for socializing children. The thesis highlights the experiences, positive and negative, that Supyire men and women have had of levirate, as related in interviews. It then begins to construct a practical theology of Supyire marriage by reflecting on it through four metaphors applied to Christ and his mission (redeemer, bridegroom, head of the church and the image of God) and the qualities particularly associated with these four metaphors (mercy, joyful love, permanent unity and respect for human dignity respectively). Despite its imperfections, the Supyire system of levirate gives security to widows and the fatherless, allows them continued access to farmland and thus to a livelihood, and can be a channel for Christ to mediate and teach about his faithful love. On these bases it is argued that levirate should be recognized by the church as a valid stage of marriage rather than treated as adultery or fornication. The thesis also reflects on the negative impact of sin on Supyire levirate and how marriage and levirate could be redeemed, with God at its centre rather than on the periphery. -

Nasal Vowel Patterns in West Africa” 1 [email protected]

UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2013) Nicholas Rolle UC Berkeley 1 “Nasal vowel patterns in West Africa” [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION Nasal vowels are a common feature of West African phonologies, and have received a significant amount of attention concerning their (suprasegmental) representation, their interaction with nasal consonants, and their phonetic realization. Numerous authors have presented surveys of varying degrees of (targeted) depth which address the distribution of contrastive nasal vowels in (West) Africa, including Hyman (1972), Williamson (1973), Ruhlen (1978), Maddieson (1984, 2007), Clements (2000), Clements & Rialland (2006), and Hajek (2011). Building on this literature, this present study provides a more extensive survey on contrastive nasal vowels in West Africa, and specifically studies the types of systematic gaps found. For example, the language Togo-Remnant language Bowili has a 7 oral vowel inventory canonical of West Africa /i e ɛ a ɔ o u/, as well as a full set of nasal counterparts /ĩ ẽ ɛ ̃ ã ɔ̃ õ ũ/ (Williamson 1973). In contrast, the Gur language Bariba has the same 7 oral vowel inventory, though a more limited nasal set /ĩ ɛ ̃ ã ɔ̃ ũ/, missing mid-high vowels */ẽ õ/ (Hyman 1972:201). Using this as a starting point, this paper addresses the following questions: . What are the recurring patterns one finds in West African nasal vowel systems and inventories? o What restrictions are there on mid vowels in the nasal inventory? . In which families/areal zones do we find these patterns? . To which factors can we attribute these patterns? o Genetic – Vertical inheritance o Areal – Horizontal spread o Universal Phonetic – Parallel Developments . -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Aguna in Benin Aja in Benin Population: 20,000 Population: 993,000 World Popl: 38,000 World Popl: 1,228,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: Yoruba People Cluster: Guinean Main Language: Aguna Main Language: Aja Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Partially reached Status: Significantly reached Evangelicals: 8.0% Evangelicals: 11.0% Chr Adherents: 35.0% Chr Adherents: 30.0% Scripture: Translation Needed Scripture: Portions www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Kerry Olson "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Anii in Benin Anufo, Chokossi in Benin Population: 47,000 Population: 25,000 World Popl: 66,000 World Popl: 229,000 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 3 People Cluster: Guinean People Cluster: Guinean Main Language: Anii Main Language: Anufo Main Religion: Islam Main Religion: Islam Status: Unreached Status: Partially reached Evangelicals: 1.00% Evangelicals: 5.0% Chr Adherents: 2.00% Chr Adherents: 10.0% Scripture: Unspecified Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Kerry Olson Source: Anonymous "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Batonu, Baruba in Benin Biali in Benin Population: 953,000 Population: 167,000 World Popl: 1,381,000 World Popl: 173,600 Total Countries: 4 Total -

Codes for the Representation of Names of Languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 Code for Comprehensive Coverage of Languages

© ISO 2003 — All rights reserved ISO TC 37/SC 2 N 292 Date: 2003-08-29 ISO/CD 639-3 ISO TC 37/SC 2/WG 1 Secretariat: ON Codes for the representation of names of languages — Part 3: Alpha-3 code for comprehensive coverage of languages Codes pour la représentation de noms de langues ― Partie 3: Code alpha-3 pour un traitement exhaustif des langues Warning This document is not an ISO International Standard. It is distributed for review and comment. It is subject to change without notice and may not be referred to as an International Standard. Recipients of this draft are invited to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent rights of which they are aware and to provide supporting documentation. Document type: International Standard Document subtype: Document stage: (30) Committee Stage Document language: E C:\Documents and Settings\여동희\My Documents\작업파일\ISO\Korea_ISO_TC37\심의문서\심의중문서\SC2\N292_TC37_SC2_639-3 CD1 (E) (2003-08-29).doc STD Version 2.1 ISO/CD 639-3 Copyright notice This ISO document is a working draft or committee draft and is copyright-protected by ISO. While the reproduction of working drafts or committee drafts in any form for use by participants in the ISO standards development process is permitted without prior permission from ISO, neither this document nor any extract from it may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form for any other purpose without prior written permission from ISO. Requests for permission to reproduce this document for the purpose of selling it should be addressed as shown below or to ISO's member body in the country of the requester: [Indicate the full address, telephone number, fax number, telex number, and electronic mail address, as appropriate, of the Copyright Manger of the ISO member body responsible for the secretariat of the TC or SC within the framework of which the working document has been prepared.] Reproduction for sales purposes may be subject to royalty payments or a licensing agreement. -

The Numeral System of Proto-Niger-Congo: a Step-By-Step Reconstruction

The numeral system of Proto- Niger-Congo A step-by-step reconstruction Konstantin Pozdniakov language Niger-Congo Comparative Studies 2 science press Niger-Congo Comparative Studies Chief Editor: Valentin Vydrin (INALCO – LLACAN, CNRS, Paris) Editors: Larry Hyman (University of California, Berkeley), Konstantin Pozdniakov (IUF – INALCO – LLACAN, CNRS, Paris), Guillaume Segerer (LLACAN, CNRS, Paris), John Watters (SIL International, Dallas, Texas). In this series: 1. Watters, John R. (ed.). East Benue-Congo: Nouns, pronouns, and verbs. 2. Pozdniakov, Konstantin. The numeral system of Proto-Niger-Congo: A step-by-step reconstruction. The numeral system of Proto- Niger-Congo A step-by-step reconstruction Konstantin Pozdniakov language science press Konstantin Pozdniakov. 2018. The numeral system of Proto-Niger-Congo: A step-by-step reconstruction (Niger-Congo Comparative Studies 2). Berlin: Language Science Press. This title can be downloaded at: http://langsci-press.org/catalog/book/191 © 2018, Konstantin Pozdniakov Published under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Licence (CC BY 4.0): http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 978-3-96110-098-9 (Digital) 978-3-96110-099-6 (Hardcover) DOI:10.5281/zenodo.1311704 Source code available from www.github.com/langsci/191 Collaborative reading: paperhive.org/documents/remote?type=langsci&id=191 Cover and concept of design: Ulrike Harbort Typesetting: Sebastian Nordhoff Proofreading: Ahmet Bilal Özdemir, Alena Wwitzlack-Makarevich, Amir Ghorbanpour, Aniefon Daniel, Brett Reynolds, Eitan Grossman, Ezekiel Bolaji, Jeroen van de Weijer, Jonathan Brindle, Jean Nitzke, Lynell Zogbo, Rosetta Berger, Valentin Vydrin Fonts: Linux Libertine, Libertinus Math, Arimo, DejaVu Sans Mono Typesetting software:Ǝ X LATEX Language Science Press Unter den Linden 6 10099 Berlin, Germany langsci-press.org Storage and cataloguing done by FU Berlin Ирине Поздняковой Contents Acknowledgments vii Abbreviations ix 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Niger-Congo: the state of research and the prospects for recon- struction ..............................