Multi-Level Voting in Vertically Simultaneous Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Political Corruption in Ukraine

NATIONAL SECURITY & DEFENCE π 7 (111) CONTENTS POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UKRAINE: ACTORS, MANIFESTATIONS, 2009 PROBLEMS OF COUNTERING (Analytical Report) ................................................................................................... 2 Founded and published by: SECTION 1. POLITICAL CORRUPTION AS A PHENOMENON: APPROACHES TO DEFINITION ..................................................................3 SECTION 2. POLITICAL CORRUPTION IN UKRAINE: POTENTIAL ACTORS, AREAS, MANIFESTATIONS, TRENDS ...................................................................8 SECTION 3. FACTORS INFLUENCING THE EFFECTIVENESS OF COUNTERING UKRAINIAN CENTRE FOR ECONOMIC & POLITICAL STUDIES POLITICAL CORRUPTION ......................................................................33 NAMED AFTER OLEXANDER RAZUMKOV SECTION 4. CONCLUSIONS AND PROPOSALS ......................................................... 40 ANNEX 1 FOREIGN ASSESSMENTS OF THE POLITICAL CORRUPTION Director General Anatoliy Rachok LEVEL IN UKRAINE (INTERNATIONAL CORRUPTION RATINGS) ............43 Editor-in-Chief Yevhen Shulha ANNEX 2 POLITICAL CORRUPTION: SPECIFICITY, SCALE AND WAYS Layout and design Oleksandr Shaptala OF COUNTERING IN EXPERT ASSESSMENTS ......................................44 Technical & computer support Volodymyr Kekuh ANNEX 3 POLITICAL CORRUPTION: SCALE AND WAYS OF COUNTERING IN PUBLIC PERCEPTIONS AND ASSESSMENTS ...................................49 This magazine is registered with the State Committee ARTICLE of Ukraine for Information Policy, POLITICAL -

For Free Distribution

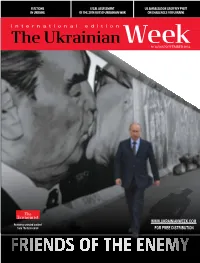

ELECTIONS LeGAL ASSESSMENT US AMBASSADOR GeOFFREY PYATT IN UKRAINE OF THE 2014 RuSSO-UKRAINIAN WAR ON CHALLENGES FOR UKRAINE № 14 (80) NOVEMBER 2014 WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM Featuring selected content from The Economist FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION |CONTENTS BRIEFING Lobbymocracy: Ukraine does not have Rapid Response Elections: The victory adequate support in the West, either in of pro-European parties must be put political circles, or among experts. The to work toward rapid and irreversible situation with the mass media and civil reforms. Otherwise it will quickly turn society is slightly better into an equally impressive defeat 28 4 Leonidas Donskis: An imagined dialogue on several clichés and misperceptions POLITICS 30 Starting a New Life, Voting as Before: Elections in the Donbas NEIGHBOURS 8 Russia’s gangster regime – the real story Broken Democracy on the Frontline: “Unhappy, poorly dressed people, 31 mostly elderly, trudged to the polls Karen Dawisha, the author of Putin’s to cast their votes for one of the Kleptocracy, on the loyalty of the Russian richest people in Donetsk Oblast” President’s team, the role of Ukraine in his grip 10 on power, and on Russia’s money in Europe Poroshenko’s Blunders: 32 The President’s bloc is painfully The Bear, Master of itsT aiga Lair: reminiscent of previous political Russians support the Kremlin’s path towards self-isolation projects that failed bitterly and confrontation with the West, ignoring the fact that they don’t have a realistic chance of becoming another 12 pole of influence in the world 2014 -

Ukraine and Occupied Crimea

y gathering 39 local scholars, experts, and civil society activists specialized in racism and human rights, the fourth edition of the European Islamophobia Report addresses a still timely and politically important issue. All 34 country Breports included in this book follow a unique structure that is convenient, first, for com- EUROPEAN paring country reports and, second, for selected readings on a particular topic such as politics, employment, or education with regards to Islamophobia across Europe. ISLAMOPHOBIA The present report investigates in detail the underlying dynamics that directly or indirectly support the rise of anti-Muslim racism in Europe. This extends from Islamophobic state- ments spread in national media to laws and policies that restrain the fundamental rights REPORT of European Muslim citizens. As a result, the European Islamophobia Report 2018 dis- cusses the impact of anti-Muslim discourse on human rights, multiculturalism, and the 2018 state of law in Europe. This fourth edition of our report highlights how European societies are challenged by the ENES BAYRAKLI • FARID HAFEZ (Eds) rise of violent far-right groups that do not only preach hatred of Muslims but also partici- pate in the organization of bloody terror attacks. The rise of far-right terrorist groups such as AFO (Action of Operational Forces) in France or the network Hannibal in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland confirms EUROPOL’s alarming surveys on the growing danger of right-wing terrorism. This year, SETA worked in cooperation with the Leopold Weiss Institute, an Austrian NGO based in Vienna dedicated to the research of Muslims in Europe. In addition, the Euro- pean Union has funded the European Islamophobia Report 2018 through the program EUROPEAN ISLAMOPHOBIA REPORT 2018 “Civil Society Dialogue Between EU and Turkey (CSD-V)”. -

Ukraine at the Crossroad in Post-Communist Europe: Policymaking and the Role of Foreign Actors Ryan Barrett [email protected]

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 1-20-2018 Ukraine at the Crossroad in Post-Communist Europe: Policymaking and the Role of Foreign Actors Ryan Barrett [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Barrett, Ryan, "Ukraine at the Crossroad in Post-Communist Europe: Policymaking and the Role of Foreign Actors" (2018). Dissertations. 725. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/725 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ukraine at the Crossroad in Post-Communist Europe: Policymaking and the Role of Foreign Actors Ryan Barrett M.A. Political Science, The University of Missouri - Saint Louis, 2015 M.A. International Relations, Webster University, 2010 B.A. International Studies, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School at the The University of Missouri - Saint Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor Philosophy in Political Science May 2018 Advisory Committee: Joyce Mushaben, Ph.D. Jeanne Wilson, PhD. Kenny Thomas, Ph.D. David Kimball, Ph.D. Contents Introduction 1 Chapter I. Policy Formulation 30 Chapter II. Reform Initiatives 84 Chapter III. Economic Policy 122 Chapter IV. Energy Policy 169 Chapter V. Security and Defense Policy 199 Conclusion 237 Appendix 246 Bibliography 248 To the Pat Tillman Foundation for graciously sponsoring this important research Introduction: Ukraine at a Crossroads Ukraine, like many European countries, has experienced a complex history and occupies a unique geographic position that places it in a peculiar situation be- tween its liberal future and communist past; it also finds itself tugged in two opposing directions by the gravitational forces of Russia and the West. -

Temptation to Control

PrESS frEEDOM IN UKRAINE : TEMPTATION TO CONTROL ////////////////// REPORT BY JEAN-FRANÇOIS JULLIARD AND ELSA VIDAL ////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// AUGUST 2010 /////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// PRESS FREEDOM: REPORT OF FACT-FINDING VISIT TO UKRAINE ///////////////////////////////////////////////////////// 2 Natalia Negrey / public action at Mykhaylivska Square in Kiev in November of 2009 Many journalists, free speech organisations and opposition parliamentarians are concerned to see the government becoming more and more remote and impenetrable. During a public meeting on 20 July between Reporters Without Borders and members of the Ukrainian parliament’s Committee of Enquiry into Freedom of Expression, parliamentarian Andrei Shevchenko deplored not only the increase in press freedom violations but also, and above all, the disturbing and challenging lack of reaction from the government. The data gathered by the organisation in the course of its monitoring of Ukraine confirms that there has been a significant increase in reports of press freedom violations since Viktor Yanukovych’s election as president in February. LEGISlaTIVE ISSUES The government’s desire to control journalists is reflected in the legislative domain. Reporters Without Borders visited Ukraine from 19 to 21 July in order to accomplish The Commission for Establishing Freedom the first part of an evaluation of the press freedom situation. of Expression, which was attached to the presi- It met national and local media representatives, members of press freedom dent’s office, was dissolved without explanation NGOs (Stop Censorship, Telekritika, SNUJ and IMI), ruling party and opposition parliamentarians and representatives of the prosecutor-general’s office. on 2 April by a decree posted on the president’s At the end of this initial visit, Reporters Without Borders gave a news conference website on 9 April. -

Separatists and Russian Nationalist-Extremist Allies of The

Separatists and Russian nationalist-extremist allies of the Party of Regions call for union with Russia Today at 17:38 | Taras Kuzio The signing of an accord to prolong the Black Sea Fleet in the Crimea by 25 years not only infringes the Constitution again, but also threatens Ukraine’s territorial integrity. If a president is willing to ignore the Constitution on two big questions in less than two months in office, what will he have done to the Constitution after 60 months in office? As somebody wrote on my Facebook profile yesterday, the Constitution is now “toilet paper.” The threat to Ukraine’s territorial integrity is deeper. Since President Viktor Yanukovych’s election, Russian nationalist-extremist allies of the Party of Regions have begun to radicalize their activities. Their mix of Russophile and Sovietophile ideological views are given encouragement by cabinet ministers such as Minister of Education Dmytro Tabachnyk and First Deputy Prime Minister Volodymyr Semynozhenko. Calls, which look increasingly orchestrated, are made to change Ukraine’s national anthem, adopt Russian as a state language, transform Ukraine into a federal state and coordinate the writing of educational textbooks with Russia. On Monday, Russian nationalist-extremist allies of the Party of Regions in the Crimea organized a meeting on the anniversary of the Crimea’s annexation by the Russian empire that demanded a full military, political and economic union with Russia. Russian nationalist-extremists in the Crimea were marginalized by ex-President Leonid Kuchma after he abolished the Crimean presidential institution in 1995. Then Deputy Prime Minister Yevhen Marchuk undertook measures to subvert and undermine the Russian nationalist-extremists who came to power in the peninsula in 1994. -

THE WARP of the SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-Westernism, Russophilia, Traditionalism

HELSINKI COMMITTEE FOR HUMAN RIGHTS IN SERBIA studies17 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism... BELGRADE, 2016 THE WARP OF THE SERBIAN IDENTITY Anti-westernism, russophilia, traditionalism… Edition: Studies No. 17 Publisher: Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia www.helsinki.org.rs For the publisher: Sonja Biserko Reviewed by: Prof. Dr. Dubravka Stojanović Prof. Dr. Momir Samardžić Dr Hrvoje Klasić Layout and design: Ivan Hrašovec Printed by: Grafiprof, Belgrade Circulation: 200 ISBN 978-86-7208-203-6 This publication is a part of the project “Serbian Identity in the 21st Century” implemented with the assistance from the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Open Society Foundation – Serbia. CONTENTS Publisher’s Note . 5 TRANSITION AND IDENTITIES JOVAN KOMŠIĆ Democratic Transition And Identities . 11 LATINKA PEROVIĆ Serbian-Russian Historical Analogies . 57 MILAN SUBOTIĆ, A Different Russia: From Serbia’s Perspective . 83 SRĐAN BARIŠIĆ The Role of the Serbian and Russian Orthodox Churches in Shaping Governmental Policies . 105 RUSSIA’S SOFT POWER DR. JELICA KURJAK “Soft Power” in the Service of Foreign Policy Strategy of the Russian Federation . 129 DR MILIVOJ BEŠLIN A “New” History For A New Identity . 139 SONJA BISERKO, SEŠKA STANOJLOVIĆ Russia’s Soft Power Expands . 157 SERBIA, EU, EAST DR BORIS VARGA Belgrade And Kiev Between Brussels And Moscow . 169 DIMITRIJE BOAROV More Politics Than Business . 215 PETAR POPOVIĆ Serbian-Russian Joint Military Exercise . 235 SONJA BISERKO Russia and NATO: A Test of Strength over Montenegro . -

The Impact of Changes in Electoral Systems: a Comparative Analysis of the Local Election in Ukraine in 2006 and 2010

STUDIA VOL. 36 POLITOLOGICZNE STUDIA I ANALIZY Olena Yatsunska The impact of changes in electoral systems: a comparative analysis of the local election in Ukraine in 2006 and 2010 KEY WORDS: local government, local elections, proportional electoral system, majoritarian electoral system, mixed majoritarian-proportional electoral system, Ukraine STUDIA I ANALIZY Having gained independence in 1991 Ukraine, like most Central and East- ern European countries, faced the need for radical Constitutional reforms, with reorganization of local government figuring high in the agenda. Like other post-soviet countries, Ukraine had to decide on the starting point and like in the neighboring countries, democratic euphoria of the early 1990s got the upper hand: local authorities were elected on March 18, 1990, while the Law On Local People’s Deputies of Ukrainian SSR and Local Self-government was adopted by Verkhovna Rada of Ukrainian SSR on December 7, 1990. Ukrain- ian Researchers in the field of local government and its reforms concur with the opinion that the present dissatisfactory state of that institution was con- ditioned by the first steps made by Ukrainian Politicians at the beginning of the ‘transition’ period. Without clear perspective of reform, during more than 20 years of Independence, Ukrainian local government has abided dozens of laws, sometimes rather contradictory and has survived more than 10 stages of restructuring. Evolution of election legislation in Ukraine is demonstrated by Table 1. The table shows that since 1994 three electoral systems have been tested in Ukraine: 1, Majoritarian, 2, Proportional except elections to village and settlement councils and 3, ‘Mixed’ system (50% Majoritarian+50% Proportional). -

The Ukrainian Weekly 2002, No.18

www.ukrweekly.com INSIDE:• Kyiv’s foreign policy: pro-Ukrainian or pro-Kuchma? — page 3. • Vote for the top Ukrainian stamps of 2001 — pages 11-13. • “A Ukrainian Summer” — a special 12-page insert. Published by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association Vol. LXX HE KRAINIANNo. 18 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MAY 5, 2002 EEKLY$1/$2 in Ukraine T U Verkhovna Rada preparesW for new convocation Chornobyl anniversary by Roman Woronowycz which the two organizations with the most seats Kyiv Press Bureau in the new Parliament have failed to find com- marked with conference mon understanding on even the most minor of KYIV – With little headway made in an effort matters. Dmytro Tabachnyk, a leading figure in to form a parliamentary majority, the Verkhovna the United Ukraine Parliamentary faction (for- at United Nations Rada undertook organizational preparations for by Andrew Nynka merly the For a United Ukraine Bloc), which has the opening session of its new convocation by claimed 165 seats in the new convocation, said UNITED NATIONS – Activists and envi- appointing a Communist as the leader of the he was not optimistic that his faction and the ronmentalists participating in an international steering committee that laid the groundwork for second largest faction, Our Ukraine, would be conference on health and the environment the first session of the Parliament. able to find common understanding to form a The vote to approve Adam Martyniuk, a for- gathered here on April 26 to mark the 16th large center-right majority. He said he thought mer second chairman in the last Parliament and anniversary of the explosion of the No. -

NATO in Europe: Between Weak European Allies and Strong

Croatian International Relations Review - CIRR XXIII (80) 2017, 5-32 ISSN 1848-5782 Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, UDC 327(1-622NATO:4:470) DOI 10.1515/cirr-2017-0019 XXIII (80) - 2017 NATO in Europe: Between Weak European Allies and Strong Influence of Russian Federation Lidija Čehulić Vukadinović, Monika Begović, Luka Jušić Abstract After the collapse of the bipolar international order, NATO has been focused on its desire to eradicate Cold War divisions and to build good relations with Russia. However, the security environment, especially in Europe, is still dramatically changing. The NATO Warsaw Summit was focused especially on NATO’s deteriorated relations with Russia that affect Europe’s security. At the same time, it looked at bolstering deterrence and defence due to many concerns coming from eastern European allies about Russia’s new attitude in international relations. The Allies agreed that a dialogue with Russia rebuilding mutual trust needs to start. In the times when Europe faces major crisis from its southern and south-eastern neighbourhood - Western Balkan countries, Syria, Libya and Iraq - and other threats, such as terrorism, coming from the so-called Islamic State, causing migration crises, it is necessary to calm down relations with Russia. The article brings out the main purpose of NATO in a transformed world, with the accent on Europe, that is constantly developing new security conditions while tackling new challenges and threats. KEY WORDS: NATO, EU, Russia, security and stability 5 Introduction Vol.XVIII, No. 66 - 2012 Vol.XVIII, XXIII (80) - 2017 The NATO summit in Warsaw, the second meeting on a high level since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, represents a cornerstone in the adaptation of the alliance to that new complex security scenario in international relations. -

Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Gospodarki Krajowej W Kutnie

Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie NR 14 GRUDZIEŃ 2020 PÓŁROCZNIK ISSN 2353-8392 KUTNO 2020 Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie Wydział Studiów Europejskich Rada Programowo-Naukowa Przewodniczący Rady: prof. dr hab. Anatoliy Romanyuk, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie Zastępca Przewodniczącego: dr hab. Zbigniew Białobłocki, Wyższa Szkoła Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie Członkowie: prof. dr hab. Wiera Burdiak, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. Jurija Fedkowycza w Czerniowcach prof. dr hab. Walerij Bebyk, Narodowy Uniwersytet Kijowski im. Tarasa Szewczenki prof. dr hab. Markijan Malski, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie prof. zw. dr hab. Lucjan Ciamaga, Wyższa Szkoła Gospodarki Krajowej w Kutnie dr hab. Krzysztof Hajder, Uniwersytet im. A. Mickiewicza w Poznaniu prof. dr hab. Walenty Baluk, Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie prof. nadzw. dr Vitaliy Lytvin, Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie prof. Pavel Pavlov, PhD, Prorektor ds Badań i Nauki Wolnego Uniwersytetu Warneńskiego prof. Galya Gercheva D.Sc, Rektor Wolnego Uniwersytetu Warneńskiego, ks. dr hab. Kazimierz Pierzchała, Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski Jana Pawła II Recenzenci zewnętrzni: prof. dr hab. Nataliya Antonyuk, Uniwersytet Opolski prof. dr hab. Walerij Denisenko Uniwersytet Narodowy im. I. Franko we Lwowie prof. zw. dr hab. Bogdan Koszel, Uniwersytet im. A. Mickiewicza w Poznaniu prof. dr hab. Janusz Soboń, Akademia im. Jakuba z Paradyża w Gorzowie Wielkopolskim prof. dr hab. Wasyl Klimonczuk, Narodowy Uniwersytet Przykarpacki im. Wasyla Stefanyka w Iwano Frankowsku prof. dr hab. Swietłana Naumkina, Narodowy Juznoukrainski Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny im. K. D. Uszynskiego w Odessie prof. dr hab. Galina Zelenjno, Instytut Etnopolitologii im. I. Kurasa w Kijowie dr hab. Krystyna Leszczyńska- Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie Redaktor naczelny: dr hab. -

Ukraine's 2006 Parliamentary And

THE INTERNATIONAL REPUBLICAN INSTITUTE ADVANCING DEMOCRACY WORLDWIDE UKRAINE PARLIAMENTARY AND LOCAL ELECTIONS MARCH 26, 2006 ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION FINAL REPORT Ukraine Parliamentary and Local Elections March 26, 2006 Election Observation Mission Final Report The International Republican Institute IRIadvancing democracy worldwide The International Republican Institute 1225 Eye Street, N.W. Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20005 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 I. Introduction 5 II. Pre-Election Period 7 A. Political Situation in Ukraine 2004-2006 7 B. Leading Electoral Blocs and Parties in the 2006 Elections 8 C. Campaign Period 11 III. Election Period 15 A. Pre-Election Meetings 15 B. Election Day 16 IV. Post-Election Analysis 19 V. Findings and Recommendations 21 Appendix I. IRI Preliminary Statement on the Ukrainian Elections 25 Appendix II. Election Observation Delegation Members 29 Appendix III. IRI in Ukraine 31 2006 Ukraine Parliamentary and Local Elections 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The International Republican Institute (IRI) received funding from the National Endowment for Democracy to deploy a 26- member international delegation to observe the pre-election en- vironment, voting and tabulation process for the March 26, 2006 elections in Ukraine. The March elections were Ukraine’s fourth parliamentary elec- tions since the country declared independence in 1991, as well as the fi rst conducted by the government of President Viktor Yushchenko. The 2006 elections were a test for the Yushchenko administration to conduct a free and fair election. The interna- tional community and mass media were watching to see if the new government would make use of administrative resources and other fraudulent means to secure the victory for its political bloc in the election.