Flying-Foxes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predicted the Impacts of Climate Change and Extreme-Weather Events on the Future

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Predicted the impacts of climate change and extreme-weather events on the future distribution of fruit bats in Australia Vishesh L. Diengdoh1, e: [email protected], ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-0797-9261 Stefania Ondei1 - e: [email protected] Mark Hunt1, 3 - e: [email protected] Barry W. Brook1, 2 - e: [email protected] 1School of Natural Sciences, University of Tasmania, Private Bag 55, Hobart TAS 7005 Australia 2ARC Centre of Excellence for Australian Biodiversity and Heritage, Australia 3National Centre for Future Forest Industries, Australia Corresponding Author: Vishesh L. Diengdoh Acknowledgements We thank John Clarke and Vanessa Round from Climate Change in Australia (https://www.climatechangeinaustralia.gov.au/)/ Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) for providing the data on extreme weather events. This work was supported by the Australian Research Council [grant number FL160100101]. Conflict of Interest None. Author Contributions bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.05.13.443960; this version posted May 14, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. -

Living with Wildlife - Flying Foxes Fact Sheet No

LIVING WITH WILDLIFE - FLYING FOXES FACT SHEET NO. 0063 Living with wildlife - Flying Foxes What are flying foxes? flying foxes use to mark their territory and to attract females during the mating season. Flying foxes, also known as fruit bats, are winged mammals belonging to the sub-order group of megabats. Unlike the smaller insectivorous microbats, the Do flying foxes carry diseases? animal navigates using their eye sight and smell, as opposed to echolocation, Like most wildlife and pets, flying foxes may carry diseases that can affect and feed on nectar, pollen and fruit. Flying foxes forage from over 100 humans. Australian Bat Lyssavirus can be transmitted directly from flying species of native plants and may supplement this diet with introduced plants foxes to humans. The risk of contracting Lyssavirus is extremely low, with found in gardens, orchards and urban areas. transmission only possible through direct contact of saliva from an infected Of the four species of flying foxes native to mainland Australia, three reside animal with a skin penetrating bite or scratch. in the Gladstone Region. These species include the grey-headed flying fox Flying foxes are natural hosts of the Hendra virus, however, there is no (Pteropus poliocephalus), black flying fox (Pteropus alecto) and little red evidence that the virus can be transmitted directly to humans. It is believed flying fox (Pteropus scapulatus). that the virus is transmitted from flying foxes to horses through exposure to All of these species are protected under the Nature Conservation Act urine or birthing fluids. Vaccination is the most effective way of reducing the 1992 and the grey-headed flying fox is also listed as ‘vulnerable’ under the risk of the virus infecting horses. -

Daytime Behaviour of the Grey-Headed Flying Fox Pteropus Poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an Autumn/Winter Roost

DAYTIME BEHAVIOUR OF THE GREY-HEADED FLYING FOX PTEROPUS POLIOCEPHALUS TEMMINCK (PTEROPODIDAE: MEGACHIROPTERA) AT AN AUTUMN/WINTER ROOST K.A. CONNELL, U. MUNRO AND F.R. TORPY Connell KA, Munro U and Torpy FR, 2006. Daytime behaviour of the grey-headed flying fox Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck (Pteropodidae: Megachiroptera) at an autumn/winter roost. Australian Mammalogy 28: 7-14. The grey-headed flying fox (Pteropus poliocephalus Temminck) is a threatened large fruit bat endemic to Australia. It roosts in large colonies in rainforest patches, mangroves, open forest, riparian woodland and, as native habitat is reduced, increasingly in vegetation within urban environments. The general biology, ecology and behaviour of this bat remain largely unknown, which makes it difficult to effectively monitor, protect and manage this species. The current study provides baseline information on the daytime behaviour of P. poliocephalus in an autumn/winter roost in urban Sydney, Australia, between April and August 2003. The most common daytime behaviours expressed by the flying foxes were sleeping (most common), grooming, mating/courtship, and wing spreading (least common). Behaviours differed significantly between times of day and seasons (autumn and winter). Active behaviours (i.e., grooming, mating/courtship, wing spreading) occurred mainly in the morning, while sleeping predominated in the afternoon. Mating/courtship and wing spreading were significantly higher in April (reproductive period) than in winter (non-reproductive period). Grooming was the only behaviour that showed no significant variation between sample periods. These results provide important baseline data for future comparative studies on the behaviours of flying foxes from urban and ‘natural’ camps, and the development of management strategies for this species. -

Checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia

CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation i ii CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation By Ibnu Maryanto Maharadatunkamsi Anang Setiawan Achmadi Sigit Wiantoro Eko Sulistyadi Masaaki Yoneda Agustinus Suyanto Jito Sugardjito RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) iii © 2019 RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI) Cataloging in Publication Data. CHECKLIST OF THE MAMMALS OF INDONESIA: Scientific, English, Indonesia Name and Distribution Area Table in Indonesia Including CITES, IUCN and Indonesian Category for Conservation/ Ibnu Maryanto, Maharadatunkamsi, Anang Setiawan Achmadi, Sigit Wiantoro, Eko Sulistyadi, Masaaki Yoneda, Agustinus Suyanto, & Jito Sugardjito. ix+ 66 pp; 21 x 29,7 cm ISBN: 978-979-579-108-9 1. Checklist of mammals 2. Indonesia Cover Desain : Eko Harsono Photo : I. Maryanto Third Edition : December 2019 Published by: RESEARCH CENTER FOR BIOLOGY, INDONESIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCES (LIPI). Jl Raya Jakarta-Bogor, Km 46, Cibinong, Bogor, Jawa Barat 16911 Telp: 021-87907604/87907636; Fax: 021-87907612 Email: [email protected] . iv PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION This book is a third edition of checklist of the Mammals of Indonesia. The new edition provides remarkable information in several ways compare to the first and second editions, the remarks column contain the abbreviation of the specific island distributions, synonym and specific location. Thus, in this edition we are also corrected the distribution of some species including some new additional species in accordance with the discovery of new species in Indonesia. -

Flying-Fox Dispersal Feasibility Study Cassia Wildlife Corridor, Coolum Beach and Tepequar Drive Roost, Maroochydore

Sunshine Coast Council Flying-Fox Dispersal Feasibility Study Cassia Wildlife Corridor, Coolum Beach and Tepequar Drive Roost, Maroochydore. Environmental Operations May 2013 0 | Page Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 Purpose ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Flying-fox Mitigation Strategies .......................................................................................................... 2 State and Federal Permits ................................................................................................................... 4 Roost Management Plan .................................................................................................................... 4 Risk ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Flying-fox Dispersal Success in Australia ............................................................................................. 6 References .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Cassia Wildlife Corridor ................................................................................................................ 8 Background ........................................................................................................................................ -

TAILORMADE PEDIGREE for HOLDTHASIGREEN (FR)

28/04/2019 TAILORMADE PEDIGREE TAILORMADE PEDIGREE for HOLDTHASIGREEN (FR) Storm Cat (USA) Storm Bird (CAN) Sire: (Bay 1983) Terlingua (USA) HOLD THA T TIGER (USA) (Chesnut 2000) Beware of The Cat (USA) Caveat (USA) HOLDTHASIGREEN (FR) (Chesnut 1986) T C Kitten (USA) (Chesnut gelding 2012) Muhtathir (GB) Elmaamul (USA) Dam: (Chesnut 1995) Majmu (USA) GREENT ATHIR (FR) (Chesnut 2004) Lady Honorgreen (FR) Hero's Honor (USA) (Bay 1995) Homer Green 4Sx6Dx4D Northern Dancer, 5Sx5D Nearctic, 5Sx5D Natalma, 5Sx6S Bold Ruler, 6Sx6S Mahmoud, 6Sx6D Nearco, 6Sx6D Lady Angela, 6Sx6D Native Dancer, 6Sx6D Almahmoud, 6Sx6Dx6D Ribot, 6Dx6D Hail To Reason Last 5 starts 01/04/2019 2nd PRIX RIGHT ROYAL (Listed Race) Chantilly 15f £9,369 28/10/2018 1st PRIX ROYALOAK (Group 1) Chantilly 15f £176,982 06/10/2018 2nd QATAR PRIX DU CADRAN (Group 1) Parislongchamp 20f £60,690 09/09/2018 2nd PRIX GLADIATEUR (Group 3) Parislongchamp 15f 110y £14,159 19/08/2018 1st DARLEY PRIX KERGORLAY (Group 2) Deauville 15f £65,575 HOLDTHASIGREEN (FR), (FR 115), won 12 races (12f.15f.) in France from 4 to 6 years, 2018 and £598,547 including Prix Royal Oak, Chantilly, Gr.1, Darley Prix Kergorlay, Deauville, Gr.2, Grand Prix de Lyon Etape du Defi Galop, LyonParilly, L., G. P. de Nantes Etape du Defi du Galop, Nantes, L., Prix du Carrousel, MaisonsLaffitte, L., Prix Max Sicard Etape du Defi du Galop, Toulouse, L., Prix Right Royal, MaisonsLaffitte, L. (twice) and Prix Hubert Baguenault de Puchesse, Vichy, L., placed 11 times including second in Qatar Prix du Cadran, Parislongchamp, Gr.1, Qatar Prix Gladiateur, Chantilly, Gr.3 (twice), Prix Right Royal, Chantilly, L. -

Part Iii: Feasibility Study C: New Landfill Site Survey

PART III: FEASIBILITY STUDY C: NEW LANDFILL SITE SURVEY Supporting Report Chapter III-C PART III-C: NEW LANDFILL SITE SURVEY 1 Introduction Boracay Island is one of the popular tourist resorts in the Philippines and the number of visitors has increased year by year and the amount of solid waste generated has rapidly increased and become one of the most serious problems on the Island. Following RA9003, the MOM closed the dumping site on Boracay Island and they try to develop a new Sanitary Landfill (SLF) in Brangay Kabulihan. This part includes the results of series of surveys for the development of the Kabulihan SLF. 2 Objectives The site survey aimed to provide sufficient information and data necessary for the planning for the SLF. Specifically, the objectives of the survey on the new SLF are: - To generate topographic, cross-sections and longitudinal profiles of the site, - To establish the geological setting of the site including seismic condition, - To determine the nature and characteristics of the geological strata, - To obtain surface water quality upstream, downstream and within the site and groundwater quality at the site both during dry and wet seasons, - To obtain the presence of landfill gases and record odor at and adjacent to the site, - To document other relevant environmental conditions including ecological conditions, - To prepare conceptual design of the new SLF as desk study for the feasibility study, - To estimate the cost of the development of new SLF, - To complete an environmental assessment, including appropriate mitigation measures and a suitable management program, and - Drafting of the report amended from the existing IEE Report. -

Figs1 ML Tree.Pdf

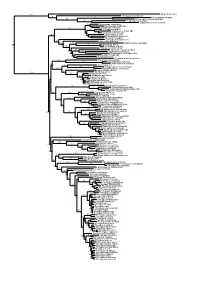

100 Megaderma lyra Rhinopoma hardwickei 71 100 Rhinolophus creaghi 100 Rhinolophus ferrumequinum 100 Hipposideros armiger Hipposideros commersoni 99 Megaerops ecaudatus 85 Megaerops niphanae 100 Megaerops kusnotoi 100 Cynopterus sphinx 98 Cynopterus horsfieldii 69 Cynopterus brachyotis 94 50 Ptenochirus minor 86 Ptenochirus wetmorei Ptenochirus jagori Dyacopterus spadiceus 99 Sphaerias blanfordi 99 97 Balionycteris maculata 100 Aethalops alecto 99 Aethalops aequalis Thoopterus nigrescens 97 Alionycteris paucidentata 33 99 Haplonycteris fischeri 29 Otopteropus cartilagonodus Latidens salimalii 43 88 Penthetor lucasi Chironax melanocephalus 90 Syconycteris australis 100 Macroglossus minimus 34 Macroglossus sobrinus 92 Boneia bidens 100 Harpyionycteris whiteheadi 69 Harpyionycteris celebensis Aproteles bulmerae 51 Dobsonia minor 100 100 80 Dobsonia inermis Dobsonia praedatrix 99 96 14 Dobsonia viridis Dobsonia peronii 47 Dobsonia pannietensis 56 Dobsonia moluccensis 29 Dobsonia anderseni 100 Scotonycteris zenkeri 100 Casinycteris ophiodon 87 Casinycteris campomaanensis Casinycteris argynnis 99 100 Eonycteris spelaea 100 Eonycteris major Eonycteris robusta 100 100 Rousettus amplexicaudatus 94 Rousettus spinalatus 99 Rousettus leschenaultii 100 Rousettus aegyptiacus 77 Rousettus madagascariensis 87 Rousettus obliviosus Stenonycteris lanosus 100 Megaloglossus woermanni 100 91 Megaloglossus azagnyi 22 Myonycteris angolensis 100 87 Myonycteris torquata 61 Myonycteris brachycephala 33 41 Myonycteris leptodon Myonycteris relicta 68 Plerotes anchietae -

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter

The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter Number 29 November 2007 ABS Website: http://abs.ausbats.org.au ABS Listserver: http://listserv.csu.edu.au/mailman/listinfo/abs ISSN 1448-5877 The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter, Number 29, November 2007 – Instructions for contributors – The Australasian Bat Society Newsletter will accept contributions under one of the following two sections: Research Papers, and all other articles or notes. There are two deadlines each year: 31st March for the April issue, and 31st October for the November issue. The Editor reserves the right to hold over contributions for subsequent issues of the Newsletter, and meeting the deadline is not a guarantee of immediate publication. Opinions expressed in contributions to the Newsletter are the responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australasian Bat Society, its Executive or members. For consistency, the following guidelines should be followed: • Emailed electronic copy of manuscripts or articles, sent as an attachment, is the preferred method of submission. Manuscripts can also be sent on 3½” floppy disk, preferably in IBM format. Please use the Microsoft Word template if you can (available from the editor). Faxed and hard copy manuscripts will be accepted but reluctantly! Please send all submissions to the Newsletter Editor at the email or postal address below. • Electronic copy should be in 11 point Arial font, left and right justified with 16 mm left and right margins. Please use Microsoft Word; any version is acceptable. • Manuscripts should be submitted in clear, concise English and free from typographical and spelling errors. Please leave two spaces after each sentence. -

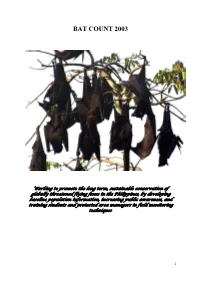

Bat Count 2003

BAT COUNT 2003 Working to promote the long term, sustainable conservation of globally threatened flying foxes in the Philippines, by developing baseline population information, increasing public awareness, and training students and protected area managers in field monitoring techniques. 1 A Terminal Report Submitted by Tammy Mildenstein1, Apolinario B. Cariño2, and Samuel Stier1 1Fish and Wildlife Biology, University of Montana, USA 2Silliman University and Mt. Talinis – Twin Lakes Federation of People’s Organizations, Diputado Extension, Sibulan, Negros Oriental, Philippines Photo by: Juan Pablo Moreiras 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Large flying foxes in insular Southeast Asia are the most threatened of the Old World fruit bats due to deforestation, unregulated hunting, and little conservation commitment from local governments. Despite the fact they are globally endangered and play essential ecological roles in forest regeneration as seed dispersers and pollinators, there have been only a few studies on these bats that provide information useful to their conservation management. Our project aims to promote the conservation of large flying foxes in the Philippines by providing protected area managers with the training and the baseline information necessary to design and implement a long-term management plan for flying foxes. We focused our efforts on the globally endangered Philippine endemics, Acerodon jubatus and Acerodon leucotis, and the bats that commonly roost with them, Pteropus hypomelanus, P. vampyrus lanensis, and P. pumilus which are thought to be declining in the Philippines. Local participation is an integral part of our project. We conducted the first national training workshop on flying fox population counts and conservation at the Subic Bay area. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Retinotopic Organization of the Primary Visual Cortex of Flying Foxes (Pteropus Poliocephalus and Pteropus Scapulatus)

THE JOURNAL OF COMPARATIVE NEUROLOGY 33555-72 ( 1993) Retinotopic Organization of the Primary Visual Cortex of Flying Foxes (Pteropus poliocephalus and Pteropus scapulatus) MARCELLO G.P. ROSA, LEISA M. SCHMID, LEAH A. KRUBITZER, AND JOHN D. PETTIGREW Vision, Touch and Hearing Research Centre, Department of Physiology and Pharmacology, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia QLD 4072, Australia ABSTRACT The representation of the visual field in the occipital cortex was studied by multiunit recordings in seven flying foxes (Pteropus spp.), anesthetized with thiopentone/NzO and immobilized with pancuronium bromide. On the basis of its visuotopic organization and architecture, the primary visual area (Vl) was distinguished from neighboring areas. Area V1 occupies the dorsal surface of the occipital pole, as well as most of the tentorial surface of the cortex, the posterior third of the mesial surface of the brain, and the upper bank of the posterior portion of the splenial sulcus. In each hemisphere, it contains a precise, visuotopically organized representation of the entire extent of the contralateral visual hemifield. The representation of the vertical meridian, together with 8-15" of ipsilateral hemifield, forms the anterior border of V1 with other visually responsive areas. The representation of the horizontal meridian runs anterolateral to posteromedial, dividing V1 so that the lower visual quadrant is represented medially, and the upper quadrant laterally. The total surface area of V1 is about 140 mm2for P. poliocephalus, and 110 mm2 for P. scapulatus. The representation of the central visual field is greatly magnified relative to that of the periphery. The cortical magnification factor decreases with increasing eccentricity, following a negative power function.