Simon-Pierre Perret and Marie-Laure Ragot, Paul Dukas Journal of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906)

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906) Paul Dukas (1865-1935) was a French composer, critic, scholar and teacher. A studious man, of retiring personality, he was intensely self-critical, and as a perfectionist he abandoned and destroyed many of his compositions. His best known work is the orchestral piece The Sorcerer's Apprentice (L'apprenti sorcier), the fame of which became a matter of irritation to Dukas. In 2011, the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians observed, "The popularity of L'apprenti sorcier and the exhilarating film version of it in Disney's Fantasia possibly hindered a fuller understanding of Dukas, as that single work is far better known than its composer." Among his other surviving works are the opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue (Ariadne and Bluebeard, 1897, later championed by Toscanini and Beecham), a symphony (1896), two substantial works for solo piano (Sonata, 1901, and Variations, 1902) and a sumptuous oriental ballet La Péri (1912). Described by the composer as a "poème dansé" it depicts a young Persian prince who travels to the ends of the Earth in a quest to find the lotus flower of immortality, coming across its guardian, the Péri (fairy). Because of the very quiet opening pages of the ballet score, the composer added a brief "Fanfare pour précéder La Peri" which gave the typically noisy audiences of the day time to settle in their seats before the work proper began. Today the prelude is a favorite among orchestral brass sections. At a time when French musicians were divided into conservative and progressive factions, Dukas adhered to neither but retained the admiration of both. -

Polyeucte, by Paul Dukas. David Procházka, the University of Akron

The University of Akron From the SelectedWorks of David Procházka 2018 Polyeucte, by Paul Dukas. David Procházka, The University of Akron Available at: https://works.bepress.com/david-prochazka/1/ Paul Dukas (b. Paris, 1 October 1865 - d. Paris, 17 May 1935) Polyeucte Overturefor orchestra ( 1891 ) Preface Paul Abraham Dukas was a French musician who worked as a critic, composer, editor, teacher, and inspector of music institutions across France. He was the middle of three children. His mother was a pianist, and his father was a banker. The familywas of Jewish descent, but seemed to focus more on thecultural life of Paris than on religious matters. Show ing some musical talent in his adolescence, Dukas' fatherencouraged him to enroll in the Conservatoire de Paris, which he did at the age of 16. It was here that Dukas began a life-long friendshipwith Claude Debussy, who was three years his senior. While Dukas was moderately successfulas a student, the crowning Prix de Rome eluded him in four successive years. In 1886 and 1887, he did not reach the finals; in 1888 he submitted the cantata Vel/eda, and in 1889 he offeredthe cantata Semele, neither of which were chosen as the winning composition. Discouraged, Dukas leftthe Conservatoire to fulfill his military service. He returnedto Paris and began a dual career as critic and composer in 1891. With time, Dukas also became a music editor, working on modem editions of works by Rameau, Couperin, Scarlatti, and Beethoven. He returnedto the Conservatoireto teach orchestration ( 1910-1913) and composition (beginning in 1928); he also taught at the Ecole Nonnale. -

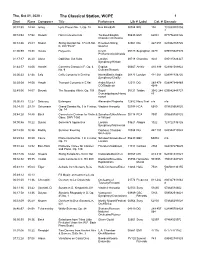

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Oct 01, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 12:24 Grieg Lyric Pieces No. 1, Op. 12 Eva Knardahl 00984 BIS 104 731859000104 2 00:14:5417:52 Rosetti Horn Concerto in E Tuckwell/English 00835 EMI 62031 077776203126 Chamber Orchestra 00:33:46 25:43 Mozart String Quartet No. 17 in B flat, Emerson String 02061 DG 427 657 028942765726 K. 458 "Hunt" Quartet 01:00:5915:38 Dukas Polyeucte Czech 05728 Supraphon 3479 099925347925 Philharmonic/Almeida 01:17:37 26:20 Alwyn Odd Man Out Suite London 08718 Chandos 9243 095115924327 Symphony/Hickox 01:44:5714:06 Handel Concerto Grosso in F, Op. 6 English 00667 Archiv 410 899 028941089922 No. 9 Concert/Pinnock 02:00:33 27:35 Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Harrell/Berlin Radio 00473 London 414 387 028941438720 Symphony/Chailly 02:29:0814:58 Haydn Trumpet Concerto in E flat Andre/Munich 12311 DG 289 479 028947946489 CO/Stadlmair 4648 02:45:06 14:07 Dvorak The Noonday Witch, Op. 108 Royal 05127 Teldec 3942-244 639842448727 Concertgebouw/Harno 87 ncourt 03:00:4312:27 Debussy Estampes Alexandre Pirojenko 12882 Novy Svet n/a n/a 03:14:1029:18 Schumann Grand Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Vladimir Horowitz 02598 RCA 6680 078635668025 Op. 14 03:44:28 14:48 Bach Concerto in D minor for Violin & Spivakov/Utkin/Mosco 00114 RCA 7991 078635799125 Oboe, BWV 1060 w Virtuosi 04:00:4610:22 Dukas Sorcerer's Apprentice London 03621 Allegro 1022 723722336126 Symphony/Mackerras 04:12:08 16:26 Kodaly Summer Evening Orpheus Chamber 10084 DG 447 109 028944710922 Orchestra 04:29:3430:20 Fauré Piano Quartet No. -

Syapnony Orcncstrs INCORPORATED THIRTY-NINTH SEASON ^^^N^ I9I9-I920

m I \ \ .• BOSTON SYAPnONY ORCnCSTRS INCORPORATED THIRTY-NINTH SEASON ^^^n^ I9I9-I920 PRoGRT^^nnC ^'21 1| Established 1833 WEBSTERi AND i ATLAS i NATIONAL BANKi OF BOSTON \ WASHINGTON AND COURT STREETS AMORY ELIOT President RAYMOND B. COX. Vice-President In ?mI\^'t.^?^<! ^\ ^"i!*' JOSEPH L. FOSTER. Vice-President and Cashier ARTHUR WTL^.Vbst.CMhie'r EDWARD M. HOWLAND, Vice-President HAROLD A. YEAMES, Asst Cashier Capital $1,000,000 Surplus and Profits $1,600,000 Deposits $11,000,000 The well-estabKshed position of this bank in the community^ the character of its Board of Directors, and its reputation as a solid, conservative institution recommend it as a particularly desirable depository for Accounts of TRUSTEES, EXECUTORS and INDIVIDUALS For commercial accounts it is known as A STRONG BANK OF DEPENDABLE SERVICE DIRECTORS CHARLES B. BARNES GRANVILLE E. FOSS JOSEPH S. BIGELOW ROBERT H. GARDINER FESSENDEN S. BLANCHARD EDWARD W. GREW THEODORE G. BREMER OLIVER HALL WILLIAM R. CORDINGLEY WALTER HUNNEWELL RAYMOND B. COX HOMER B. RICHARDSON AMORY ELIOT DUDLEY P^ROGERS ROGER ERNST THOMAS W. THACHER JOHN W. FARWELL WALTER TUFTS SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Telephones Ticket Office j { Back Bay' 1492 Branch Lxchange ( Administration Umces ) ^ Bd at Oil SfmpIboBf OirduBstra INCORPORATED THIRTY-NINTH SEASON, 1919-1920 PIERRE MONTEUX, Conductor ^"^oi"^:rammt) of tt. T'\vm^\]}J''{{Te>[ Concerts WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE FRIDAY AFTERNOON. APRIL 9 AT 2.30 O'CLOCK SATURDAY EVENING, APRIL 10 AT 8.00 O'CLOCK COPYRIGHT, 1920, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INCORPORATED W. H. BRENNAN. Manager G. -

Polyeucte Pierre Corneille (1606-1684)

1/19 Data Polyeucte Pierre Corneille (1606-1684) Langue : Français Genre ou forme de l’œuvre : Œuvres textuelles Date : 1643 Note : Tragédie en 5 actes Domaines : Littératures Détails du contenu (3 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Voir aussi (1) Polyeucte : film , Camille de Morlhon (1911) (1869-1952) Voir l'œuvre musicale (1) Polyeucte. H 498 , Marc Antoine Charpentier (1679) (1643-1704) Table des matières (1) Paris : Garnier frères , 1880 (1880) data.bnf.fr 2/19 Data Éditions de Polyeucte (236 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Livres (197) Polyeucte martyr, tragédie , Pierre Corneille Polyeucte martyr, tragédie , Pierre Corneille (par P. Corneille) (1606-1684), (S. l.) , (S. d.) chrétienne en cinq actes (1606-1684), Paris : Barbré , [s. d.] Polyeucte , Pierre Corneille Corneille. Polyeucte , Pierre Corneille (1606-1684), [Édition non (1606-1684), Paris, Gigord précisée] ; (Hué, impr. de Vien-De) , (s. d.). In-16 (175 x 120), 128 p. [D. L. Impr.] -XcTh- . 10887. Polyeucte , A. Naudin, Pierre Corneille Polyeucte martyr, tragédie , Pierre Corneille (1606-1684), Paris : Jules (par P. Corneille) (1606-1684), (S. l.) , (S. d.) Delalain , [s.d.] Corneille. Polyeucte, , Pierre Corneille [Anecdotes sur] Polyeucte, , Pierre Corneille martyr, tragédie chrétienne. (1606-1684), Genève, tragédie... (1606-1684), (S. l. n. d.) Texte annoté par M. Raoux Georg , (s. d.). In-16, 111 p. [Don 338682] -XcTh- Polyeucte martyr , Pierre Corneille Polyeucte , Pierre Corneille (2002) (1606-1684), Paris : (1996) (1606-1684), [Paris] : Librairie générale française -

Abstracts Abstracts

180 Abstracts Abstracts Giselher Schubert: Paul Dukas: Melancholy Assets As a composer, music critic and composition teacher, Paul Dukas counts among the most representative French musicians of the turn to the 20th cen- tury. Even though he attended the Conservatoire de Paris, he had to pass for a self-taught person. He held close and friendly contact with almost all composers of his time, yet he was basically a loner. His compositorial work is conceivably small, and after 1911, he hardly published any works though his creativity did not ebb at all. His music reviews belong to the most substantial contributions to the musical life of the time; composers like Joaquin Rodrigo or Olivier Messiaen studied with him. In the 1920s, during a time of traditions getting lost, Dukas tried in several essays to regain tradition in an original way. Übersetzung: Claudia Brusdeylins * Dominik Rahmer: »Minerve instruisant Euterpe«. On the Musical Criticism of Paul Dukas’ Dukas’ activity as a music critic occupied a dominant part of his early career. His substantial analyses differ greatly from the contemporary day-to-day critique or the subjective and biased articles like those of his friend Debussy. While Dukas’ methodological approach shows parallels to contemporary lit- erary criticism as Ferdinand Brunetière’s »critique érudite«, his historiographi- cal thinking is marked by the influence of the 19th-ct. philosopher Herbert Spencer. Dukas’ writings aim at fostering the appreciation of a broad range of music from different aesthetic strains, at least until World War I, after which he shifted his attention to teaching. * Arne Stollberg: Between »musique traductrice« and »musique pure«. -

DUKAS Complete Piano Music

557053bk Dukas 13/06/2003 9:57 am Page 8 DDD DUKAS 8.557053 Complete Piano Music Piano Sonata Variations on a Theme of Rameau Chantal Stigliani, Piano Paul Dukas (1865-1935) Photo LIPNITZKI - VIOLLE 8.557053 8 557053bk Dukas 13/06/2003 9:57 am Page 2 Paul Dukas (1865-1935) l’on ne saurait déceler la moindre faiblesse – de ton, de Les sept premières variations sont essentiellement Complete Piano Music pensée, d’écriture- et où la conclusion, grandiose, élargit mélodiques : I, contrepoint ; II, fermeté rythmique ; III et en une suprême dimension les données énoncées dans IV : le thème évolue à la basse, au soprano, d’une main à Paul Dukas was born in Paris on 1st October 1865 and The great Sonata in E flat minor is composed on a les toutes premières mesures. l’autre ; V, polyphonie modulante ; VI, imitation en died there on 17th May 1935. Although his catalogue of grander scale altogether. Dedicated to Saint-Saëns, it Le triptyque Variations, Interlude et Finale terminé écho ; VII, capricante. published works is small, it is of the highest quality, was first performed in Paris’s Salle Pleyel on 10th May en février 1902 et créé également par Risler le 23 mars Les variations VIII à XI s’animent : en arpèges consisting essentially of one overture, Polyeucte, one 1901 by Edouard Risler. It followed the sweeping 1903 à la SNM constitue un autre défi : que la moindre (VIII), en rythme de gigue (IX), de sarabande (X), dans symphony, one symphonic scherzo (the immortal Symphony in C and L’apprenti sorcier of 1896-97 and is idée musicale peut générer d’impressionnants un climat très doux (X). -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Branch Exchange Telephone, Ticket and Administration Offices, Com. 1492 FIFTY-FIFTH SEASON, 1935-1936 CONCERT BULLETIN of the Boston Symphony Orchestra INCORPORATED Dr. SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor RICHARD Burgin, Assistant Conductor with historical and descriptive notes By John N. Burk COPYRIGHT, 1935, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. The OFFICERS and TRUSTEES of the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. Bentley W. Warren President Henry B. Sawyer Vice-President Ernest B. Dane Treasurer Allston Burr Roger I. Lee Henry B. Cabot William Phillips Ernest B. Dane Henry B. Sawyer N. Penrose Hallowell Pierpont L. Stackpole M. A. De Wolfe Howe Edward A. Taft Bentley W. Warren G. E. JUDD, Manager C. W. SPALDING, Assistant Manager [49] c£ wM cemAanu ib to betue (obia/ek ab (oxectde-r- and monetae ^ronm ok zJ^K^tee <w ab S^laent. <mu7Tuearb o>£ exfoewience and a wm/uete o^ant^aiion ename ab fa omsk eJlicient and AwmAt bewwce. Old Colony Trust Company 17 COURT STREET, BOSTON ^Allied with The First National Bank of Boston [50] Contents Title Page ......... Page 49 Programme ......... 53 Analytical Notes: Mozart Symphony in E-flat major ... 55 Dukas "La Peri," Danced Poem .... 62 Strauss "Death and Transfiguration" ... 78 Strauss "Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks" . 84 The First Critics of "Till" ...... 86 Entr'acte: Prunieres "Farewell to Dukas" . 71 Frederick Pickering Cabot, first President of the Boston Symphony Orchestra .....= 65 The Next Programme ....... 89 Events in Symphony Hall ...... 90 Concert Announcements ...... 91 Teachers' Directory ....... 93-96 Personnel ....... Opposite page 96 [51] Cfjantler & Co. TREMONT AND WEST STREETS Magnificent Jap Mink Coats $295 Unusual values at this price These coats have all the at- tributes of style and quality. -

JOURNAL DES DÉBATS, 19 Mai 1907, Pp. 1-2. Allons, Décidément, C

JOURNAL DES DÉBATS, 19 mai 1907, pp. 1-2. Allons, décidément, c’est Ariane et Barbe-Bleue qui a pris le pas sur le Chandelier… Voici un ouvrage considérable, et dont l’importance est double à nos yeux, car le poème est de M. Maurice Mæterlinck, vers qui tant de compositeurs se tournent aujourd’hui depuis le grand succès de son Pelléas et Mélisande orné d’une musique qu’il semblait tout d’abord réprouver, et la partition a pour auteur un des plus brillants coloristes qui soient dans l’art des sons parmi les jeunes représentants de l’école française. En effet, M. Paul Dukas n’a pas tout à fait quarante-deux ans révolus et s’il en est encore à faire ses premiers pas sur la scène, il a déjà pris une place importante dans les concerts et le succès remporté de tous côtés par son Apprenti Sorcier, une des pages de musique descriptive les plus spirituelles et les plus richement instrumentées qui se puissent voir, l’a tiré de pair après la réussite déjà fort honorable de son ouverture de Polyeucte et de sa grande Symphonie, très solidement écrites l’une et l’autre, où perçait un rare instinct de la couleur orchestrale et des effets des timbres; mais qui ne l’avaient pas encore poussé en pleine lumière. Après avoir donné ces témoignages de plus en plus remarqués d’un talent très sur – n’oublions pas de citer aussi sa sonate pour piano seul et ses variations sur un thème de Rameau – M. Dukas a vu s’offrir à lui l’occasion de rattraper le temps perdu et de se poser, au théâtre, à côté de tant de compositeurs qui furent ou plus favorisés que lui au concours de Rome, puisqu’il n’y obtint qu’un second prix en 1888, ou mieux servis par les circonstances, et qui l’ont devancé depuis longtemps sur l’une ou l’autre de ces grandes scènes lyriques: nul doute qu’il ne sache y réussir. -

Pascal Dusapin Nicolas Hodges PANTOMIME Piano À QUIA · AUFGANG Carolin Widmann Paulwenn DU DEM WIND

PASCALPASCAL ROPHÉ ROPHÉ albert Roussel Le Festin de l’araignée BALLET-Pascal Dusapin Nicolas Hodges PANTOMIME piano À QUIA · AUFGANG Carolin Widmann PaulWENN DU DEM WIND... violin Dukas Natascha Petrinsky mezzo-soprano L’Apprenti sorcier Orchestre National des Polyeucte Pays de la Loire ouverture Pascal Rophé ORCHESTRE NATIONAL DES PAYS DE LA LOIRE PASCAL ROPHÉ BIS-2262 DUKAS, Paul (1865—1935) 1 Polyeucte (1891) 14'23 Overture to the tragedy by Pierre Corneille ROUSSEL, Albert (1869—1937) Le Festin de l’Araignée (The Spider’s Feast), Op. 17 (1912—13) 32'45 Pantomime ballet in one act to a libretto by Gilbert de Voisins 2 Prélude — Un Jardin (Prelude — A Garden) 4'29 Sitting in her web, a spider watches the surroundings 3 Entrée des Fourmis (Entrance of the Ants) 3'10 The ants discover a rose petal. Struggling to lift it they carry it off. Left alone, the spider dreamily watches the garden. — She checks the strength of the thread and mends the web. 4 Entrée des Bousiers (Entrance of the Dung Beetles) 1'02 The ants return and prepare to carry off another petal when a butterfly appears. 5 Danse du Papillon (Dance of the Butterfly) 4'14 The spider lures the butterfly towards her web. — Caught in the web the butterfly struggles to get free. — Death of the butterfly. The spider rejoices. — She frees the butterfly from the web and takes it to her larder. 6 Danse de l’Araignée (The Spider Dances) 1'52 Suddenly fruits come crashing down from a tree. The spider jumps backwards. -

Winter 2019-20/2

Second Thoughts and Short Reviews Winter 2019-2020/2 By Brian Wilson, Dan Morgan and Johan van Veen Reviews are by Brian Wilson unless otherwise stated. Winter #1 is here and Autumn 2019 #2 here. Index [page numbers in brackets; later page numbers may be slightly displaced] BACH Six Partitas for harpsichord (Clavier Übung I) - Ton Koopman_Challenge Classics [7] - Cantatas Nos. 82, 84 and 199 – Christine Schäfer_Sony [7] BANTOCK Violin Sonata No.3; SCOTT Viola Sonata; SACHEVERELL COKE Violin Sonata No.1 - Rupert Marshall-Luck; Matthew Rickard_EM Records [20] BARTH, GADE, KUHLAU – 19th Century Danish Overtures - Aarhus Symphony Orchestra/Jean Thorel _DaCapo [14] BEETHOVEN 250 – new and old releases_Various performers and labels [10] - Piano Concertos Nos. 1-5 – Rudolf Brautigam; Kölner Akademie/Michael Willens_BIS [12] - Late String Quartets – Cypress Quartet_Avie [13] - String Quartet No.14 – Jaspere Quartet_Sono Luminus [13] BERNARDI Lux æterna – Voces Suaves_Arcana [3] BRIDGE Phantasie for string quartet; HOLST Phantasy on British Folksongs; GOOSSENS Phantasy Quartet for strings; HOWELLS Phantasy String Quartet; HOLBROOKE First Quartet Fantasie; HURLSTONE Phantasie for string quartet - The Bridge Quartet_EM Records [19] BUXTEHUDE Membra Jesu Nostri - RossoPorpora Ensemble/Testolin_Stradivarius[4] CIMAROSA 21 Organ Sonatas – Andrea Chezzi_Brilliant Classics [10] COLONNA O splendida dies – Scherzi Musicali/Achten_Ricercar [5] DUKAS L’Apprenti Sorcier; Polyeucte Overture – Loire Orchestra/Pascal Rophé_BIS (with ROUSSEL) [17] ELGAR Violin Sonata: see GURNEY GESUALDO Madrigals – Exaudi Ensemble/Weeks_Winter and Winter [3] GOOSSENS Phantasy Concerto for Violin and Orchestra; Symphony No.2 – Tasmin Little; Melbourne SO/Andrew Davis_Chandos [20] GÓRECKI Symphony No.3 – Adeliade SO/Yuasa_ABC [22] GURNEY Violin Sonata in E-flat; SAINSBURY Soliloquy for Solo Violin; ELGAR Violin Sonata - Rupert Marshall-Luck; Matthew Rickard (piano)_EM Records [19] HAYDN Symphonies Nos. -

The Sorcerer's Apprentice Paul Dukas

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice Paul Dukas (1865–1935) Written: 1897 Movements: One Style: Romantic Duration: 11 minutes Near the end of his life, the composer Paul Dukas burned all but a very small portion of his life’s work. If he were alive today, he may have wished that he left more music around, because his reputation rests on one piece. Here in America, were it not for Mickey Mouse and Disney’s 1940 film Fantasia, contemporary American audiences might know nothing of Paul Dukas. Paul Dukas’ father was a banker and his mother was an accomplished pianist who died when he was only five. Although he played the piano as a child, Paul didn’t show any real aptitude toward music until he turned fourteen. When he was sixteen, he enrolled at the Paris Conservatory, where he befriended the slightly older Claude Debussy. Even though Paul did well as a student, he dropped out. He was frustrated that he couldn’t win any of those prizes, like the coveted Prix de Rome, that helped establish so many composers. After a short stint in the military, he started a career as a music critic and composed. He wrote an overture in 1892, Polyeucte, that received some acclaim, as did his Symphony in C, which he wrote four years later. However, it was in 1897, when he wrote The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, that the world suddenly acknowledged Paul Dukas. Later, he wrote an opera based on the story of Bluebeard that is still admired in France. Dukas set such high standards for himself that he rarely released any of his music.