Pictures at an Exhibition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music You Know & Schubert

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, April 29, 2016, 8:00pm MUSIC YOU KNOW: STORYTELLING David Robertson, conductor Celeste Golden Boyer, violin BERNSTEIN Candide Overture (1956) (1918-1990) PONCHIELLI Dance of the Hours from La Gioconda (1876) (1834-1886) VITALI/ Chaconne in G minor for Violin and Orchestra (ca. 1705/1911) orch. Charlier (1663-1745) Celeste Golden Boyer, violin INTERMISSION HUMPERDINCK Prelude to Hänsel und Gretel (1893) (1854-1921) DUKAS The Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1897) (1865-1935) STEFAN FREUND Cyrillic Dreams (2009) (b. 1974) David Halen, violin Alison Harney, violin Jonathan Chu, viola Daniel Lee, cello WAGNER/ Ride of the Valkyries from Die Walküre (1856) arr. Hutschenruyter (1813-1883) 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This concert is part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral Series. This concert is part of the Whitaker Foundation Music You Know Series. This concert is supported by University College at Washington University. David Robertson is the Beofor Music Director and Conductor. The concert of Friday, April 29, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Mr. and Mrs. Andrew C. Taylor. The concert of Friday, April 29, is the Joanne and Joel Iskiwitch Concert. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of the Delmar Gardens Family and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 A FEW THINGS YOU MIGHT NOT KNOW ABOUT MUSIC YOU KNOW BY EDDIE SILVA For those of you who stayed up late to watch The Dick Cavett Show on TV, you may recognize Leonard Bernstein’s Candide Overture as the theme song played by the band led by Bobby Rosengarden. -

Service Books of the Orthodox Church

SERVICE BOOKS OF THE ORTHODOX CHURCH THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. BASIL THE GREAT THE LITURGY OF THE PRESANCTIFIED GIFTS 2010 1 The Service Books of the Orthodox Church. COPYRIGHT © 1984, 2010 ST. TIKHON’S SEMINARY PRESS SOUTH CANAAN, PENNSYLVANIA Second edition. Originally published in 1984 as 2 volumes. ISBN: 978-1-878997-86-9 ISBN: 978-1-878997-88-3 (Large Format Edition) Certain texts in this publication are taken from The Divine Liturgy according to St. John Chrysostom with appendices, copyright 1967 by the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America, and used by permission. The approval given to this text by the Ecclesiastical Authority does not exclude further changes, or amendments, in later editions. Printed with the blessing of +Jonah Archbishop of Washington Metropolitan of All America and Canada. 2 CONTENTS The Entrance Prayers . 5 The Liturgy of Preparation. 15 The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom . 31 The Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great . 101 The Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. 181 Appendices: I Prayers Before Communion . 237 II Prayers After Communion . 261 III Special Hymns and Verses Festal Cycle: Nativity of the Theotokos . 269 Elevation of the Cross . 270 Entrance of the Theotokos . 273 Nativity of Christ . 274 Theophany of Christ . 278 Meeting of Christ. 282 Annunciation . 284 Transfiguration . 285 Dormition of the Theotokos . 288 Paschal Cycle: Lazarus Saturday . 291 Palm Sunday . 292 Holy Pascha . 296 Midfeast of Pascha . 301 3 Ascension of our Lord . 302 Holy Pentecost . 306 IV Daily Antiphons . 309 V Dismissals Days of the Week . -

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions

Wichita Symphony Youth Orchestras Acceptable Repertoire for Youth Talent Auditions Repertoire not listed below may be acceptable, but must be pre-approved. Contact Tiffany Bell at [email protected] to request approval for repertoire not on this list. Violin Bach: Concerto No. 1 in A Minor Bach: Concerto No. 2 in E Major Barber: Concerto, Op. 14, first movement Beethoven: Concerto in D Major, Op. 61 Beethoven: Romance No. 1 in G Major Beethoven: Romance No. 2 in F Major Brahms: Concerto, third movement Bruch: Concerto No. 1 in G Minor, Op. 26, any movement Bruch: Scottish Fantasy Conus: Concerto in E Minor, first movement Dvorak: Romance Haydn: Concerto in C Major, Hob.VIIa Kabalevsky: Concerto, Op. 48, first or third movement Khachaturian: Violin Concert, Allegro Vivace, first movement Lalo: Symphonie Espagnole, first or fifth movement Mendelssohn: Concerto in E Minor, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 3 in G Major, K. 216, any movement Mozart: Concerto No. 4 in D Major, K. 218, first movement Mozart: Concerto No. 5 in A Major, K. 219, first movement Saint-Saens: Introduction and Rondo Capriccios, Op. 28 Saint-Saens: Concerto No. 3 in B Minor, Op. 61 Saint-Saens: Havanaise Sarasate: Zigeunerweisen, Op. 20 Sibelius: Concerto in D Minor, fist movement Tchaikovsky: Concerto, third movement Vitali: Chaconne Wieniawski: Legend, Op. 17 Wieniawski: Concerto in D Minor Viola J.C. Bach/Casadesus: Concerto in C Minor, Adagio-Allegro Bach: Concerto in D Minor, first movement Forsythe: Concerto for Viola, first movement Handel/Casadesus: Concerto in B Minor Hoffmeister Concerto Stamitz: Concerto in D Major Telemann: Concerto in G Major Cello Boccherini: Concerto Bruch: Kol Nidrei Dvorak: Concerto in B Minor, Op. -

June 2018 UCL ALUMNI LONDON GROUP

UCL Alumni London Group Events, January - June 2018 UCL ALUMNI Contact: John McKenzie (Administrator), 51 Clifford Road, Barnet, Herts EN5 5PD (020 8447 1396) LONDON GROUP 1. Thursday 25 January, at 2.15 pm. Prime-mover: Dennis Wilmot (Psychology 1983) Wine Tasting Tasting: Argentina, not just Malbec! Venue: the Nyholm Room, UCL Chemistry Department. London Group events, January – June 2018 Something to counteract the post-Christmas blues, starting with some Chandon sparkling white wine (Méthode Traditionelle). Taste wines from the highest winery in the world, plus other wines from high- altitude Salta in the north. Also wine from cold Patagonia in the south, plus of course Malbec and the Dear Fellow Alumni Malbec blends from Mendoza including wine costing £34 per bottle. There are more wines to taste and at a lower price than last time due to the ‘in-house’ UCL venue. Snacks from M & S / Waitrose including British Once again, I would like to thank our Prime Movers who have organised these events, which make cheeses are included. up an outstanding programme; I do hope that you will be able to attend many of them and would £30. Maximum number 15. urge you to bring friends as guests, especially former UCL students and staff, in the hope that they will wish to join the London Group in their own right. As ever we are open to suggestions from members for future events and warmly welcome anyone wishing to Prime Move an event to join the Organising Team, which meets monthly at UCL. 2. Friday 2 February, at 11.15 am. -

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906)

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906) Paul Dukas (1865-1935) was a French composer, critic, scholar and teacher. A studious man, of retiring personality, he was intensely self-critical, and as a perfectionist he abandoned and destroyed many of his compositions. His best known work is the orchestral piece The Sorcerer's Apprentice (L'apprenti sorcier), the fame of which became a matter of irritation to Dukas. In 2011, the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians observed, "The popularity of L'apprenti sorcier and the exhilarating film version of it in Disney's Fantasia possibly hindered a fuller understanding of Dukas, as that single work is far better known than its composer." Among his other surviving works are the opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue (Ariadne and Bluebeard, 1897, later championed by Toscanini and Beecham), a symphony (1896), two substantial works for solo piano (Sonata, 1901, and Variations, 1902) and a sumptuous oriental ballet La Péri (1912). Described by the composer as a "poème dansé" it depicts a young Persian prince who travels to the ends of the Earth in a quest to find the lotus flower of immortality, coming across its guardian, the Péri (fairy). Because of the very quiet opening pages of the ballet score, the composer added a brief "Fanfare pour précéder La Peri" which gave the typically noisy audiences of the day time to settle in their seats before the work proper began. Today the prelude is a favorite among orchestral brass sections. At a time when French musicians were divided into conservative and progressive factions, Dukas adhered to neither but retained the admiration of both. -

2019 CCPA Solo Competition: Approved Repertoire List FLUTE

2019 CCPA Solo Competition: Approved Repertoire List Please submit additional repertoire, including concertante pieces, to both Dr. Andrizzi and to your respective Department Head for consideration before the application deadline. FLUTE Arnold, Malcolm: Concerto for flute and strings, Op. 45 strings Arnold, Malcolm: Concerto No 2, Op. 111 orchestra Bach, Johann Sebastian: Suite in B Minor BWV1067, Orchestra Suite No. 2, strings Bach, Carl Philipp Emanuel: Concerto in D Minor Wq. 22, strings Berio, Luciano: Serenata for flute and 14 instruments Bozza, Eugene: Agrestide Op. 44 (1942) orchestra Bernstein, Leonard: Halil, nocturne (1981) strings, percussion Bloch, Ernest: Suite Modale (1957) strings Bloch, Ernest: "TWo Last Poems... maybe" (1958) orchestra Borne, Francois: Fantaisie Brillante on Bizet’s Carmen orchestra Casella, Alfredo: Sicilienne et Burlesque (1914-17) orchestra Chaminade, Cecile: Concertino, Op. 107 (1902) orchestra Chen-Yi: The Golden Flute (1997) orchestra Corigliano, John: Voyage (1971, arr. 1988) strings Corigliano, John: Pied Piper Fantasy (1981) orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto No. 7 in E Minor, orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto No. 10 in D Major, orchestra Devienne, Francois: Concerto in D Major, orchestra Doppler, Franz: Hungarian Pastoral Fantasy, Op. 26, orchestra Feld, Heinrich: Fantaisie Concertante (1980) strings, percussion Foss, Lucas: Renaissance Concerto (1985) orchestra Godard, Benjamin: Suite Op. 116; Allegretto, Idylle, Valse (1889) orchestra Haydn, Joseph: Concerto in D Major, H. VII f, D1 Hindemith, Paul: Piece for flute and strings (1932) Hoover, Katherine: Medieval Suite (1983) orchestra Hovhaness, Alan: Elibris (name of the DaWn God of Urardu) Op. 50, (1944) Hue, Georges: Fantaisie (1913) orchestra Ibert, Jaques: Concerto (1933) orchestra Jacob, Gordon: Concerto No. -

Louis Lortie Sunday, April 9, 2017 at 3:00 Pm This Is the 714Th Concert in Koerner Hall

Invesco Piano Concerts Louis Lortie Sunday, April 9, 2017 at 3:00 pm This is the 714th concert in Koerner Hall ALL FRYDERYK CHOPIN PROGRAM 12 Études, Op. 10 Étude No. 1, in C Major (‘Waterfall’) Étude No. 2, in A Minor (‘Chromatic’) Étude No. 3, in E Major (‘Tristesse’) Étude No. 4, in C-sharp Minor (‘Torrent’) Étude No. 5, in G-flat Major (‘Black Keys’) Étude No. 6, in E-flat Minor Étude No. 7, in C Major (‘Torrent’) Étude No. 8, in F Major (‘Sunshine’) Étude No. 9, in F Minor Étude No. 10, in A-flat Major Étude No. 11, in E-flat Major (‘Arpeggio’) Étude No. 12, in C Minor (‘Revolutionary’) 12 Études, Op. 25 Étude No. 1, in A-flat Major (‘Aeolian harp’) Étude No. 2, in F Minor (‘Bees’) Étude No. 3, in F Major (‘Cartwheel’/‘Horseman’) Étude No. 4, in A Minor Étude No. 5, in E Minor (‘Wrong notes’) Étude No. 6, in G-sharp Minor (‘Thirds’) Étude No. 7, in C-sharp Minor (‘Cello’) Étude No. 8, in D-flat Major (‘Sixths’) Étude No. 9, in G-flat Major (‘Butterfly’) Étude No. 10, in B Minor (‘Octaves’) Étude No. 11, in A Minor (‘Winter wind’) Étude No. 12, in C Minor (‘Ocean’) INTERMISSION 24 Preludes, Op. 28 1. Prelude in C Major (Agitato) 2 Prelude in A Minor (Lento) 3. Prelude in G Major (Vivace) 4. Prelude in E Minor (Largo) 5. Prelude in D Major (Molto allegro) 6 Prelude in B Minor (Lento assai) 7. Prelude in A Major (Andantino) 8. -

7655 Libretto Online Layout 1

DYNAMIC Charles Gounod POLYEUCTE Opera in four acts Libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré LIBRETTO with parallel English translation CD 1 CD 1 1 PRELUDE 1 PRELUDE ACTE PREMIER FIRST ACT PREMIER TABLEAU FIRST TABLEAU La chambre de Pauline. Porte au fond. A droite, l’autel des dieux domestiques. Une The apartments of Paulina. A door in the back. On the right, the altar of the lampe placée sur l’autel éclaire la scène. household gods. A lamp on the altar illuminates the scene. Scène Première First scene Pauline, Stratonice, Suivantes. Paulina, Stratonice, Maids. Au lever du rideau, les Suivantes, groupées autour de Stratonice, sont occupées à As the curtain rises, the Maids, assembled around Stratonice, are busy carrying out divers travaux. Pauline est penchée sur l’autel des dieux domestiques. different tasks. Paulina is leaning over the altar of the household gods. 2 Le Chœur – Déjà dans l’azur des cieux 2 Chorus – In the blue skies Apparaît de Phœbé le char silencieux ; Phebus’s silent chariot already appears; C’est l’heure du travail nocturne ; It is time for our night tasks; Apprêtez vos fuseaux, puisez l’huile dans l’urne ; Prepare your spindles, draw oil from the urn; Le doux sommeil plus tard viendra fermer vos yeux. Later sweet slumber will close your eyes. Stratonice – A chacune de nous sa tâche accoutumée. Stratonice – Each of us to their own tasks. (S’approchant de Pauline) (Approaching Paulina) Mais vous, ô mon enfant, maîtresse bien-aimée, But you, my child, beloved mistress, Quel noir souci tient votre âme alarmée ? What dark worry troubles your heart? Pauline – J’implore tout bas les dieux familiers Paulina – I implore the household gods, Gardiens de nos amours, gardiens de nos foyers !.. -

Sfcm.Edu/Bachelor-Of-Music Bachelor of Music Candidates for The

sfcm.edu/bachelor-of-music Bachelor of Music Candidates for the Bachelor of Music degree are required to complete a minimum of 127 credits for graduation. Bachelor of Music candidates must satisfactorily complete at least 28 credits in residence at the Conservatory during the junior and/or senior years. A maximum of six years is allowed between time of entrance and completion of the Bachelor of Music degree. Students who major in either performance or composition typically receive weekly 50-minute lessons. All students are allowed 14 lessons in the fall semester and 15 lessons in the spring semester. Private instruction must be taken with a member of the Conservatory collegiate faculty. Recitals And Juries At the conclusion of each academic year, students will be required to perform before faculty jurors. Students who enter in January will play their jury examinations in December of that calendar year. These examinations determine whether the student has satisfactorily completed yearly requirements in the major instrument and influence continuing eligibility for scholarship assistance. The jury examination is taken into account when determining the grade for PVL 100/110/112R. Jury examination and recital requirements vary according to the major field. These requirements including repertoire are listed below by individual major instrument following the course requirements. No required recitals or juries can be given unless the student is registered for PVL 100/110/112R at the time of the recital or jury. No required recitals or juries can be given outside of the regular collegiate sessions. Exceptions to this policy are only given in extreme cases. -

Louis Lortie Volume 2 Bridgeman Images / 1942) – Portrait by Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861

In paradisum A FAURÉ R ECITAL Louis Lortie Volume 2 Gabriel Fauré, c. 1887 Portrait by Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861 – 1942) / Bridgeman Images Gabriel Fauré (1845 – 1924) 1 Pie Jesu from Requiem, Op. 48 (1887 – 88) 3:47 Transcribed for solo piano by Louis Lortie Paisible et illuminé – Très lointain – A tempo – [Très lointain] – Un poco meno mosso 2 Barcarolle No. 12, Op. 106 bis (1915) 3:16 in E flat major • in Es-Dur • en mi bémol majeur Allegretto giocoso 3 Nocturne No. 11, Op. 104 No. 1 (1913) 4:55 in F sharp minor • in fis-Moll • en fa dièse mineur In memoriam Noémi Lalo Molto moderato 4 Ballade, Op. 19 (1877 – 79) 14:33 in F sharp major • in Fis-Dur • en fa dièse majeur Andante cantabile – Lento – Allegro moderato – Andante – Un poco più mosso – Allegro – Andante – Allegro moderato 3 5 Nocturne No. 7, Op. 74 (1898) 8:05 in C sharp minor • in cis-Moll • en ut dièse mineur À Mme Adéla Maddison Molto lento – Un poco più mosso – Tempo I – Allegro – Molto lento – Un poco più mosso Thème et variations, Op. 73 (1895) 15:27 in C sharp minor • in cis-Moll • en ut dièse mineur À Mademoiselle Thérèse Roger 6 [Thème.] Quasi Adagio – 1:33 7 Variation 1. Lo stesso tempo – 0:55 8 Variation 2. Più mosso – 0:45 9 Variation 3. Un poco più mosso – 0:39 10 Variation 4. Lo stesso tempo – 1:17 11 Variation 5. Un poco più mosso – 0:40 12 Variation 6. Molto Adagio – 1:45 13 Variation 7. -

Polyeucte, by Paul Dukas. David Procházka, the University of Akron

The University of Akron From the SelectedWorks of David Procházka 2018 Polyeucte, by Paul Dukas. David Procházka, The University of Akron Available at: https://works.bepress.com/david-prochazka/1/ Paul Dukas (b. Paris, 1 October 1865 - d. Paris, 17 May 1935) Polyeucte Overturefor orchestra ( 1891 ) Preface Paul Abraham Dukas was a French musician who worked as a critic, composer, editor, teacher, and inspector of music institutions across France. He was the middle of three children. His mother was a pianist, and his father was a banker. The familywas of Jewish descent, but seemed to focus more on thecultural life of Paris than on religious matters. Show ing some musical talent in his adolescence, Dukas' fatherencouraged him to enroll in the Conservatoire de Paris, which he did at the age of 16. It was here that Dukas began a life-long friendshipwith Claude Debussy, who was three years his senior. While Dukas was moderately successfulas a student, the crowning Prix de Rome eluded him in four successive years. In 1886 and 1887, he did not reach the finals; in 1888 he submitted the cantata Vel/eda, and in 1889 he offeredthe cantata Semele, neither of which were chosen as the winning composition. Discouraged, Dukas leftthe Conservatoire to fulfill his military service. He returnedto Paris and began a dual career as critic and composer in 1891. With time, Dukas also became a music editor, working on modem editions of works by Rameau, Couperin, Scarlatti, and Beethoven. He returnedto the Conservatoireto teach orchestration ( 1910-1913) and composition (beginning in 1928); he also taught at the Ecole Nonnale. -

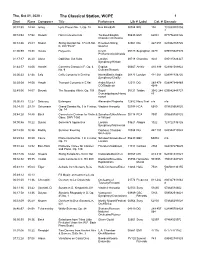

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Oct 01, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 12:24 Grieg Lyric Pieces No. 1, Op. 12 Eva Knardahl 00984 BIS 104 731859000104 2 00:14:5417:52 Rosetti Horn Concerto in E Tuckwell/English 00835 EMI 62031 077776203126 Chamber Orchestra 00:33:46 25:43 Mozart String Quartet No. 17 in B flat, Emerson String 02061 DG 427 657 028942765726 K. 458 "Hunt" Quartet 01:00:5915:38 Dukas Polyeucte Czech 05728 Supraphon 3479 099925347925 Philharmonic/Almeida 01:17:37 26:20 Alwyn Odd Man Out Suite London 08718 Chandos 9243 095115924327 Symphony/Hickox 01:44:5714:06 Handel Concerto Grosso in F, Op. 6 English 00667 Archiv 410 899 028941089922 No. 9 Concert/Pinnock 02:00:33 27:35 Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Harrell/Berlin Radio 00473 London 414 387 028941438720 Symphony/Chailly 02:29:0814:58 Haydn Trumpet Concerto in E flat Andre/Munich 12311 DG 289 479 028947946489 CO/Stadlmair 4648 02:45:06 14:07 Dvorak The Noonday Witch, Op. 108 Royal 05127 Teldec 3942-244 639842448727 Concertgebouw/Harno 87 ncourt 03:00:4312:27 Debussy Estampes Alexandre Pirojenko 12882 Novy Svet n/a n/a 03:14:1029:18 Schumann Grand Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Vladimir Horowitz 02598 RCA 6680 078635668025 Op. 14 03:44:28 14:48 Bach Concerto in D minor for Violin & Spivakov/Utkin/Mosco 00114 RCA 7991 078635799125 Oboe, BWV 1060 w Virtuosi 04:00:4610:22 Dukas Sorcerer's Apprentice London 03621 Allegro 1022 723722336126 Symphony/Mackerras 04:12:08 16:26 Kodaly Summer Evening Orpheus Chamber 10084 DG 447 109 028944710922 Orchestra 04:29:3430:20 Fauré Piano Quartet No.