Polyeucte, by Paul Dukas. David Procházka, the University of Akron

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Service Books of the Orthodox Church

SERVICE BOOKS OF THE ORTHODOX CHURCH THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. BASIL THE GREAT THE LITURGY OF THE PRESANCTIFIED GIFTS 2010 1 The Service Books of the Orthodox Church. COPYRIGHT © 1984, 2010 ST. TIKHON’S SEMINARY PRESS SOUTH CANAAN, PENNSYLVANIA Second edition. Originally published in 1984 as 2 volumes. ISBN: 978-1-878997-86-9 ISBN: 978-1-878997-88-3 (Large Format Edition) Certain texts in this publication are taken from The Divine Liturgy according to St. John Chrysostom with appendices, copyright 1967 by the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America, and used by permission. The approval given to this text by the Ecclesiastical Authority does not exclude further changes, or amendments, in later editions. Printed with the blessing of +Jonah Archbishop of Washington Metropolitan of All America and Canada. 2 CONTENTS The Entrance Prayers . 5 The Liturgy of Preparation. 15 The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom . 31 The Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great . 101 The Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. 181 Appendices: I Prayers Before Communion . 237 II Prayers After Communion . 261 III Special Hymns and Verses Festal Cycle: Nativity of the Theotokos . 269 Elevation of the Cross . 270 Entrance of the Theotokos . 273 Nativity of Christ . 274 Theophany of Christ . 278 Meeting of Christ. 282 Annunciation . 284 Transfiguration . 285 Dormition of the Theotokos . 288 Paschal Cycle: Lazarus Saturday . 291 Palm Sunday . 292 Holy Pascha . 296 Midfeast of Pascha . 301 3 Ascension of our Lord . 302 Holy Pentecost . 306 IV Daily Antiphons . 309 V Dismissals Days of the Week . -

Allusions and Historical Models in Gaston Leroux's the Phantom of the Opera

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Honors Theses Carl Goodson Honors Program 2004 Allusions and Historical Models in Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera Joy A. Mills Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons, Other Theatre and Performance Studies Commons, and the Translation Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mills, Joy A., "Allusions and Historical Models in Gaston Leroux's The Phantom of the Opera" (2004). Honors Theses. 83. https://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/honors_theses/83 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Carl Goodson Honors Program at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gaston Leroux's 1911 novel, The Phantom of the Opera, has a considerable number of allusions, some of which are accessible to modern American audiences, like references to Romeo and Juilet. Many of the references, however, are very specific to the operatic world or to other somewhat obscure fields. Knowledge of these allusions would greatly enhance the experience of readers of the novel, and would also contribute to their ability to interpret it. Thus my thesis aims to be helpful to those who read The Phantom of the Opera by providing a set of notes, as it were, to explain the allusions, with an emphasis on the extended allusion of the Palais Garnier and the historical models for the heroine, Christine Daae. Notes on Translations At the time of this writing, three English translations are commercially available of The Phantom of the Opera. -

The Reception of Herculanum in the Contemporary Press

The reception of Herculanum in the contemporary press Gunther Braam How can the success of an opera in its own time be examined and studied? Quite simply, by working out the number of performances and the total amount of receipts generated, then by creating – and assess - ing – the most extensive dossier possible of the reviews which appeared in the contemporary press. herculanum : from playbill to box office With regard to the number of performances, the Journal de l’Opéra , today held in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, is fortunately at our dis - posal. Nevertheless, this needs to be analysed carefully, not overlooking the fact that the presence of an opera in the repertory might well result from reasons other than artistic ones, such as the departure of a direct- or, those connected with the singers entrusted with the leading roles, the destruction of scenery (often as a result of fires), for political reasons or for all kinds of other possibilities. Examples which could be mentioned include Tannhäuser by Wagner (1861), or – why not also – the less well- known La Nonne sanglante by Gounod (1854): far from being unsuccess - ful in terms of audience levels, these two operas were withdrawn after three performances for Tannhäuser , and eleven for La Nonne sanglant e; the average receipts for the two operas were respectively 8,890 and 6,140 francs (in comparison, the receipts for a performance of Les Huguenots 77 félicien david: herculanum in 1859, typically ranged between 6,000 and 7,000 francs). How does Herculanum compare to other -

June 2018 UCL ALUMNI LONDON GROUP

UCL Alumni London Group Events, January - June 2018 UCL ALUMNI Contact: John McKenzie (Administrator), 51 Clifford Road, Barnet, Herts EN5 5PD (020 8447 1396) LONDON GROUP 1. Thursday 25 January, at 2.15 pm. Prime-mover: Dennis Wilmot (Psychology 1983) Wine Tasting Tasting: Argentina, not just Malbec! Venue: the Nyholm Room, UCL Chemistry Department. London Group events, January – June 2018 Something to counteract the post-Christmas blues, starting with some Chandon sparkling white wine (Méthode Traditionelle). Taste wines from the highest winery in the world, plus other wines from high- altitude Salta in the north. Also wine from cold Patagonia in the south, plus of course Malbec and the Dear Fellow Alumni Malbec blends from Mendoza including wine costing £34 per bottle. There are more wines to taste and at a lower price than last time due to the ‘in-house’ UCL venue. Snacks from M & S / Waitrose including British Once again, I would like to thank our Prime Movers who have organised these events, which make cheeses are included. up an outstanding programme; I do hope that you will be able to attend many of them and would £30. Maximum number 15. urge you to bring friends as guests, especially former UCL students and staff, in the hope that they will wish to join the London Group in their own right. As ever we are open to suggestions from members for future events and warmly welcome anyone wishing to Prime Move an event to join the Organising Team, which meets monthly at UCL. 2. Friday 2 February, at 11.15 am. -

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906)

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906) Paul Dukas (1865-1935) was a French composer, critic, scholar and teacher. A studious man, of retiring personality, he was intensely self-critical, and as a perfectionist he abandoned and destroyed many of his compositions. His best known work is the orchestral piece The Sorcerer's Apprentice (L'apprenti sorcier), the fame of which became a matter of irritation to Dukas. In 2011, the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians observed, "The popularity of L'apprenti sorcier and the exhilarating film version of it in Disney's Fantasia possibly hindered a fuller understanding of Dukas, as that single work is far better known than its composer." Among his other surviving works are the opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue (Ariadne and Bluebeard, 1897, later championed by Toscanini and Beecham), a symphony (1896), two substantial works for solo piano (Sonata, 1901, and Variations, 1902) and a sumptuous oriental ballet La Péri (1912). Described by the composer as a "poème dansé" it depicts a young Persian prince who travels to the ends of the Earth in a quest to find the lotus flower of immortality, coming across its guardian, the Péri (fairy). Because of the very quiet opening pages of the ballet score, the composer added a brief "Fanfare pour précéder La Peri" which gave the typically noisy audiences of the day time to settle in their seats before the work proper began. Today the prelude is a favorite among orchestral brass sections. At a time when French musicians were divided into conservative and progressive factions, Dukas adhered to neither but retained the admiration of both. -

La Fille Du Régiment

LELELELE BUGUE BUGUEBUGUEBUGUE Salle Eugène Le Roy Réservation : Maison de la Presse Le Bugue 05 53 07 22 83 Gaetano Donizetti LA FILLE DU RÉGIMENT Orpheline, Marie was taken in by Sergeant Sulpice, who employs him as a cantinière in his regiment. Crazy in love with Marie, the young peasant Tonio engages in the battalion to see her every day. When the Marquise of Berkenfield reveals the true identity of Mary, who is her daughter, the young woman could be separated forever from Tonio. Acclaimed by the lyric press, South African soprano Pretty Yende returns to the stage of the Met opposite the tenor Javier Camarena for an opera of great vocal virtuosity under the baton of Enrique Mazzola. The alchemist Donizetti's expertise once again acts with this unique blend of melancholy and joy. Tenor Javier Camarena and soprano Pretty Yende team up for a feast of bel canto vocal fireworks—including the show-stopping tenor aria “Ah! Mes amis … Pour mon âme,” with its nine high Cs. Alessandro Corbelli and Maurizio Muraro trade off as the comic Sergeant Sulpice, with mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe as the outlandish Marquise of Berkenfield. And in an exciting piece of casting, stage and screen icon Kathleen Turner makes her Met debut in the speaking role of the Duchess of Krakenthorp. Enrique Mazzola conducts. Conductor Marie Marquise Enrique Pretty Stéphanie Mazzola Yende Blythe soprano Mezzo soprano Duchess Tonio Sulpice Kathleen Javier Maurizio Turner Camarena Muraro actress tenor Bass Production : Laurent Pelly DATE : 2nd March 2019 Time : 6.25pm Opera en 2 acts by Giacomo Puccini LA FILLE DU RÉGIMENT World Premiere : Opéra Comique, Paris, 1840. -

Fiche AC Gounod.Qxd

Les fiches pédagogiques - Compositeur CHARLES GOUNOD(1818 - 1893)hhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh Il naît à Paris le 17 juin 1818. Issu d’une famille d’artistes (père peintre et mère pro- fesseur de piano) il est attiré assez jeune vers ces matières. Après avoir obtenu son baccalauréat en 1835 , il décide de devenir musicien malgré les réticences de sa mère. A partir de 1838, il poursuit des études au conservatoire et obtient le premier Grand prix de Rome l’année suivante. Accompagné d’Hector le Fuel (architecte), il arrive à Rome le 27 janvier 1840 où la Villa Médicis est dirigée par Jean-Auguste- Dominique Ingres. Il se lie avec la sœur de Félix Mendelssohn qui lui fait découvrir les romantiques allemands. Il écrit ses premières mélodies en 1842, notamment sa Messe de Rome et un Requiem. En 1843, après un détour par Vienne, Berlin ou en- core Leipzig, il est de retour à Paris et dirige la musique à l’église des Missions étrangères jusqu’en 1848, date à laquelle cesse sa vocation religieuse. Soutenu par l’influente Pauline Viardot, il obtient une commande de l’Opéra de Paris : Sapho. La création de l’opéra le 16 avril 1851 ne fait pas grand bruit et sa reprise à Londres le 8 août est catastrophique. En revanche ses mélodies et sa musique chorale ren- contre un certain succès. Le 20 avril 1852, Gounod épouse Anna Zimmerman et à la mort de son beau-père, s'installe dans une magnifique demeure à St Cloud. En 1858, sa mère disparait alors que le succès à l'opéra arrive avec Le Médecin malgré lui (1858) et Faust (1859) où il se montre d'une sensualité délicate et émouvante et où il révèle un sens théatral évident. -

Read Book \\ Polyeucte: Opera En Quatre Actes (Classic Reprint

3XHIZ4JT0C # Polyeucte: Opera En Quatre Actes (Classic Reprint) (Paperback) eBook Polyeucte: Opera En Quatre A ctes (Classic Reprint) (Paperback) By Jules Barbier To get Polyeucte: Opera En Quatre Actes (Classic Reprint) (Paperback) eBook, remember to refer to the web link beneath and save the file or have access to additional information that are highly relevant to POLYEUCTE: OPERA EN QUATRE ACTES (CLASSIC REPRINT) (PAPERBACK) book. Our web service was introduced with a want to serve as a total on the internet digital catalogue that provides usage of large number of PDF book assortment. You will probably find many kinds of e-guide and other literatures from the paperwork data base. Specific well-liked subjects that distribute on our catalog are trending books, solution key, test test question and solution, guideline sample, exercise manual, test sample, user manual, owners guidance, support instruction, restoration manual, and many others. READ ONLINE [ 3.23 MB ] Reviews The ebook is straightforward in study better to fully grasp. It is actually loaded with knowledge and wisdom I am just delighted to tell you that here is the best pdf i have read through during my very own lifestyle and may be he greatest ebook for at any time. -- Dr. Karelle Glover Totally one of the better publication I have actually read through. It really is rally fascinating throgh studying time period. Its been printed in an extremely simple way and is particularly just following i finished reading through this ebook in which basically modified me, modify the way i think. -- Mrs. Maudie Weimann 0PUAYYAMFX > Polyeucte: Opera En Quatre Actes (Classic Reprint) (Paperback) PDF Related PDFs Games with Books : 28 of the Best Childrens Books and How to Use Them to Help Your Child Learn - From Preschool to Third Grade [PDF] Follow the web link listed below to download "Games with Books : 28 of the Best Childrens Books and How to Use Them to Help Your Child Learn - From Preschool to Third Grade" PDF file. -

Famous Composers and Their Music

iiii! J^ / Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Brigham Young University http://www.archive.org/details/famouscomposerst05thom HAROLD BLEBLffiR^^ PROVO. UTAH DANIEL FRANCOIS ESPRIT AUBER From an engraving by C. Deblois, 7867. 41 .'^4/ rii'iiMia-"- '^'', Itamous COMPOSERS AND THEIR MUSIC EXTRA ILLUSTPATED EDITION o/' 1901 Edited by Theodore Thomas John Knowlej Paine (^ Karl Klauser ^^ n .em^fssfi BOSTON M'^ J B MILLET COMPANY m V'f l'o w i-s -< & Copyright, 1891 — 1894— 1901, By J. B. Millet Company. DANIEL FRANCOIS ESPRIT AUBER LIFE aiore peaceful, happy and making for himself a reputation in the fashionable regular, nay, even monotonous, or world. He was looked upon as an agreeable pianist one more devoid of incident than and a graceful composer, with sparkling and original Auber's, has never fallen to the ideas. He pleased the ladies by his irreproachable lot of any musician. Uniformly gallantry and the sterner sex by his wit and vivacity. harmonious, with but an occasional musical dis- During this early period of his life Auber produced sonance, the symphony of his life led up to its a number of lietier, serenade duets, and pieces of dramatic climax when the dying composer lay sur- drawing-room music, including a trio for the piano, rounded by the turmoil and carnage of the Paris violin and violoncello, which was considered charm- Commune. Such is the picture we draw of the ing by the indulgent and easy-going audience who existence of this French composer, in whose garden heard it. Encouraged by this success, he wrote a of life there grew only roses without thorns ; whose more imp^i/rtant work, a concerto for violins with long and glorious career as a composer ended only orchestra, which was executed by the celebrated with his life ; who felt that he had not lived long Mazas at one of the Conservatoire concerts. -

An Inquiry Into Modes of Existence

An Inquiry into Modes of Existence An Inquiry into Modes of Existence An Anthropology of the Moderns · bruno latour · Translated by Catherine Porter Harvard University Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2013 Copyright © 2013 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America The book was originally published as Enquête sur les modes d'existence: Une anthropologie des Modernes, copyright © Éditions La Découverte, Paris, 2012. The research has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (fp7/2007-2013) erc Grant ‘ideas’ 2010 n° 269567 Typesetting and layout: Donato Ricci This book was set in: Novel Mono Pro; Novel Sans Pro; Novel Pro (christoph dunst | büro dunst) Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Latour, Bruno. [Enquête sur les modes d'existence. English] An inquiry into modes of existence : an anthropology of the moderns / Bruno Latour ; translated by Catherine Porter. pages cm “The book was originally published as Enquête sur les modes d'existence : une anthropologie des Modernes.” isbn 978-0-674-72499-0 (alk. paper) 1. Civilization, Modern—Philosophy. 2. Philosophical anthropology. I. Title. cb358.l27813 2013 128—dc23 2012050894 “Si scires donum Dei.” ·Contents· • To the Reader: User’s Manual for the Ongoing Collective Inquiry . .xix Acknowledgments . xxiii Overview . xxv • ·Introduction· Trusting Institutions Again? . 1 A shocking question addressed to a climatologist (02) that obliges us to distinguish values from the ac- counts practitioners give of them (06). Between modernizing and ecologizing, we have to choose (08) by proposing a different system of coordinates (10). -

7655 Libretto Online Layout 1

DYNAMIC Charles Gounod POLYEUCTE Opera in four acts Libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré LIBRETTO with parallel English translation CD 1 CD 1 1 PRELUDE 1 PRELUDE ACTE PREMIER FIRST ACT PREMIER TABLEAU FIRST TABLEAU La chambre de Pauline. Porte au fond. A droite, l’autel des dieux domestiques. Une The apartments of Paulina. A door in the back. On the right, the altar of the lampe placée sur l’autel éclaire la scène. household gods. A lamp on the altar illuminates the scene. Scène Première First scene Pauline, Stratonice, Suivantes. Paulina, Stratonice, Maids. Au lever du rideau, les Suivantes, groupées autour de Stratonice, sont occupées à As the curtain rises, the Maids, assembled around Stratonice, are busy carrying out divers travaux. Pauline est penchée sur l’autel des dieux domestiques. different tasks. Paulina is leaning over the altar of the household gods. 2 Le Chœur – Déjà dans l’azur des cieux 2 Chorus – In the blue skies Apparaît de Phœbé le char silencieux ; Phebus’s silent chariot already appears; C’est l’heure du travail nocturne ; It is time for our night tasks; Apprêtez vos fuseaux, puisez l’huile dans l’urne ; Prepare your spindles, draw oil from the urn; Le doux sommeil plus tard viendra fermer vos yeux. Later sweet slumber will close your eyes. Stratonice – A chacune de nous sa tâche accoutumée. Stratonice – Each of us to their own tasks. (S’approchant de Pauline) (Approaching Paulina) Mais vous, ô mon enfant, maîtresse bien-aimée, But you, my child, beloved mistress, Quel noir souci tient votre âme alarmée ? What dark worry troubles your heart? Pauline – J’implore tout bas les dieux familiers Paulina – I implore the household gods, Gardiens de nos amours, gardiens de nos foyers !.. -

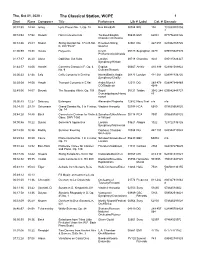

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Thu, Oct 01, 2020 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 12:24 Grieg Lyric Pieces No. 1, Op. 12 Eva Knardahl 00984 BIS 104 731859000104 2 00:14:5417:52 Rosetti Horn Concerto in E Tuckwell/English 00835 EMI 62031 077776203126 Chamber Orchestra 00:33:46 25:43 Mozart String Quartet No. 17 in B flat, Emerson String 02061 DG 427 657 028942765726 K. 458 "Hunt" Quartet 01:00:5915:38 Dukas Polyeucte Czech 05728 Supraphon 3479 099925347925 Philharmonic/Almeida 01:17:37 26:20 Alwyn Odd Man Out Suite London 08718 Chandos 9243 095115924327 Symphony/Hickox 01:44:5714:06 Handel Concerto Grosso in F, Op. 6 English 00667 Archiv 410 899 028941089922 No. 9 Concert/Pinnock 02:00:33 27:35 Lalo Cello Concerto in D minor Harrell/Berlin Radio 00473 London 414 387 028941438720 Symphony/Chailly 02:29:0814:58 Haydn Trumpet Concerto in E flat Andre/Munich 12311 DG 289 479 028947946489 CO/Stadlmair 4648 02:45:06 14:07 Dvorak The Noonday Witch, Op. 108 Royal 05127 Teldec 3942-244 639842448727 Concertgebouw/Harno 87 ncourt 03:00:4312:27 Debussy Estampes Alexandre Pirojenko 12882 Novy Svet n/a n/a 03:14:1029:18 Schumann Grand Sonata No. 3 in F minor, Vladimir Horowitz 02598 RCA 6680 078635668025 Op. 14 03:44:28 14:48 Bach Concerto in D minor for Violin & Spivakov/Utkin/Mosco 00114 RCA 7991 078635799125 Oboe, BWV 1060 w Virtuosi 04:00:4610:22 Dukas Sorcerer's Apprentice London 03621 Allegro 1022 723722336126 Symphony/Mackerras 04:12:08 16:26 Kodaly Summer Evening Orpheus Chamber 10084 DG 447 109 028944710922 Orchestra 04:29:3430:20 Fauré Piano Quartet No.