Paul Dukas' Approach to Orchestration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY of HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY OF HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK PAUL STEFAN ML 41O M23S831 c.2 MUSI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Presented to the FACULTY OF Music LIBRARY by Estate of Robert A. Fenn GUSTAV MAHLER A Study of His Personality and tf^ork BY PAUL STEFAN TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN EY T. E. CLARK NEW YORK : G. SCHIRMER COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY G. SCHIRMER 24189 To OSKAR FRIED WHOSE GREAT PERFORMANCES OF MAHLER'S WORKS ARE SHINING POINTS IN BERLIN'S MUSICAL LIFE, AND ITS MUSICIANS' MOST SPLENDID REMEMBRANCES, THIS TRANSLATION IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BERLIN, Summer of 1912. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The present translation was undertaken by the writer some two years ago, on the appearance of the first German edition. Oskar Fried had made known to us in Berlin the overwhelming beauty of Mahler's music, and it was intended that the book should pave the way for Mahler in England. From his appearance there, we hoped that his genius as man and musi- cian would be recognised, and also that his example would put an end to the intolerable existing chaos in reproductive music- making, wherein every quack may succeed who is unscrupulous enough and wealthy enough to hold out until he becomes "popular." The English musician's prayer was: "God pre- serve Mozart and Beethoven until the right man comes," and this man would have been Mahler. Then came Mahler's death with such appalling suddenness for our youthful enthusiasm. Since that tragedy, "young" musicians suddenly find themselves a generation older, if only for the reason that the responsibility of continuing Mah- ler's ideals now rests upon their shoulders in dead earnest. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Music as Representational Art Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vv9t9pz Author Walker, Daniel Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Daniel Walker 2014 © Copyright by Daniel Walker 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening by Daniel Walker Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair There are two volumes to this dissertation; the first is a monograph, and the second is a musical composition, both of which are described below. Volume I Music is a language that can be used to express a vast range of ideas and emotions. It has been part of the human experience since before recorded history, and has established a unique place in our consciousness, and in our hearts by expressing that which words alone cannot express. ii My individual interest in the musical language is its use in telling stories, and in particular in the form of composition referred to as program music; music that tells a story on its own without the aid of images, dance or text. The topic of this dissertation follows this line of interest with specific focus on the compositional techniques and creative approach that divide program music across a representational spectrum from literal to abstract. -

Ondine - Diary of a Ballet Online

6qNin [Download free ebook] Ondine - Diary of a Ballet Online [6qNin.ebook] Ondine - Diary of a Ballet Pdf Free Hans Werner Henze ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #4990267 in Books 2015-10-30Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.50 x .31 x 5.51l, .54 #File Name: 185273095176 pages | File size: 15.Mb Hans Werner Henze : Ondine - Diary of a Ballet before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Ondine - Diary of a Ballet: 2 of 2 people found the following review helpful. Dear Hans, thanks for sharing, you're the cat's pajamas. Better, you're The Cat's Fugue.By J. FaulkThese extracts, melded together, from the composer's diary were published in Germany in 1959 and in English in 2003.In 1957 Ashton and Henze meet in Ischia to convert the old German folktale Undine into a ballet scenario that choreographer, composer, and the great ballerina Fonteyn can find inspiring (as well as the traditionalist London audience). The tale commences in the hut of a fisherman and his wife and their foundling daughter, actually an ondine. The girl immediately falls in love (so far as an ondine can) with the guest Knight. It takes Ashton and Henze a long time to jettison this commonplace setting. Meanwhile, Henze's diary wanders off into appreciation of Italian life.Henze goes to London to write the music and his diary shares the milieu with us. Designer Lila De Nobili comes over from Paris and joins in the ever-shifting ideas. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

Piano; Trio for Violin, Horn & Piano) Eric Huebner (Piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (Violin); Adam Unsworth (Horn) New Focus Recordings, Fcr 269, 2020

Désordre (Etudes pour Piano; Trio for violin, horn & piano) Eric Huebner (piano); Yuki Numata Resnick (violin); Adam Unsworth (horn) New focus Recordings, fcr 269, 2020 Kodály & Ligeti: Cello Works Hellen Weiß (Violin); Gabriel Schwabe (Violoncello) Naxos, NX 4202, 2020 Ligeti – Concertos (Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Chamber Concerto for 13 instrumentalists, Melodien) Joonas Ahonen (piano); Christian Poltéra (violoncello); BIT20 Ensemble; Baldur Brönnimann (conductor) BIS-2209 SACD, 2016 LIGETI – Les Siècles Live : Six Bagatelles, Kammerkonzert, Dix pièces pour quintette à vent Les Siècles; François-Xavier Roth (conductor) Musicales Actes Sud, 2016 musica viva vol. 22: Ligeti · Murail · Benjamin (Lontano) Pierre-Laurent Aimard (piano); Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra; George Benjamin, (conductor) NEOS, 11422, 2016 Shai Wosner: Haydn · Ligeti, Concertos & Capriccios (Capriccios Nos. 1 and 2) Shai Wosner (piano); Danish National Symphony Orchestra; Nicolas Collon (conductor) Onyx Classics, ONYX4174, 2016 Bartók | Ligeti, Concerto for piano and orchestra, Concerto for cello and orchestra, Concerto for violin and orchestra Hidéki Nagano (piano); Pierre Strauch (violoncello); Jeanne-Marie Conquer (violin); Ensemble intercontemporain; Matthias Pintscher (conductor) Alpha, 217, 2015 Chorwerk (Négy Lakodalmi Tánc; Nonsense Madrigals; Lux æterna) Noël Akchoté (electric guitar) Noël Akchoté Downloads, GLC-2, 2015 Rameau | Ligeti (Musica Ricercata) Cathy Krier (piano) Avi-Music – 8553308, 2014 Zürcher Bläserquintett: -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

View Concert Program

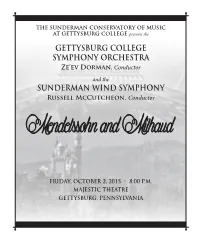

THE SUNDERMAN CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC AT GETTYSBURG COLLEGE presents the GETTYSBURG COLLEGE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Ze’ev Dorman, Conductor and the SUNDERMAN WIND SYMPHONY Russell McCutcheon, Conductor Friday, OctOber 2, 2015 • 8:00 p.m. MAJESTIC THEATRE GETTYSBURG, PENNSYLVANIA blank Program SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ZE’EV DORMAN, CONDUCTOR Symphony No.9 in C Major ............................................................................................Felix Mendelssohn -Bartholdy (1809-1847) I. Grave, Allegro II. Andante III. Scherzo IV. Allegro vivace — Intermission — WIND SYMPHONY Russell McCutcheon, Conductor Fanfare from “La Péri” ............................................................................................................... Paul Dukas (1865 – 1935) Asclepius .......................................................................................................................Michael Daugherty (b. 1954) Sechs Tänze, Op. 71 .................................................................................................................. Rolf Rudin (b. 1961) I. Breit schreitend II. Very fast III. Giocoso IV. Breit und wuchtig V. Con eleganza VI. Molto vivace Suite Française ....................................................................................................................Darius Milhaud (1892 – 1974) I. Normandy II. Brittany III. Île-de-France IV. Alsace-Lorraine V. Provence Program Notes Tonight’s program alternates between Germany and France, with a diversion to the United States in-between. The Symphony Orchestra -

June 29 to July 5.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES June 29 - July 5, 2020 PLAY DATE : Mon, 06/29/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto 6:11 AM Johann Nepomuk Hummel Serenade for Winds 6:31 AM Johan Helmich Roman Concerto for Violin and Strings 6:46 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Symphony 7:02 AM Johann Georg Pisendel Concerto forViolin,Oboes,Horns & Strings 7:16 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Sonata No. 32 7:30 AM Jean-Marie Leclair Violin Concerto 7:48 AM Antonio Salieri La Veneziana (Chamber Symphony) 8:02 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Mensa sonora, Part III 8:12 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 34 8:36 AM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. 3 9:05 AM Leroy Anderson Concerto for piano and orchestra 9:25 AM Arthur Foote Piano Quartet 9:54 AM Leroy Anderson Syncopated Clock 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem: Communio: Lux aeterna 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Sonata No. 21, K 304/300c 10:23 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart DON GIOVANNI Selections 10:37 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata for 2 pianos 10:59 AM Felix Mendelssohn String Quartet No. 3 11:36 AM Mauro Giuliani Guitar Concerto No. 1 12:00 PM Danny Elfman A Brass Thing 12:10 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Schwärmereien Concert Waltz 12:23 PM Franz Liszt Un Sospiro (A Sigh) 12:32 PM George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue 12:48 PM John Philip Sousa Our Flirtations 1:00 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony No. 6 1:43 PM Michael Kurek Sonata for Viola and Harp 2:01 PM Paul Dukas La plainte, au loin, du faune...(The 2:07 PM Leos Janacek Sinfonietta 2:33 PM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. -

South Bay Chamber Music Society April 26 & 28, 2019 Trio Ondine

South Bay Chamber Music Society April 26 & 28, 2019 Trio Ondine Alison Bjorkedal, harp Alma Lisa Fernandez, viola Boglárka Kiss, flute Program Notes by Boglárka Kiss, D.M.A. Many standard chamber music ensembles, such as the string quartet or piano trio, have long histories with origins that are difficult to pinpoint. Not so with the flute, viola, harp formation: The first major composition written for the group was the Sonate by Claude Debussy in 1915. Inspired by the unique timbral possibilities of this trio, countless composers followed in Debussy’s footsteps, creating a rich 20th-century repertoire for the ensemble. Today’s program features works by American, French and German composers, a couple of transcriptions, as well as Debussy’s beloved and groundbreaking Sonate. Aperitif Lucas Richman (b. 1964) Lucas Richman is an award-winning conductor and composer who enjoys a diverse career. He has served as Music Director for the Bangor Symphony Orchestra since 2010 and recently completed a 12-year tenure as Music Director for the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra. Mr. Richman received a GRAMMY Award in 2011 for having conducted the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on Christopher Tin’s classical/world fusion album, Calling All Dawns. Mr. Richman’s numerous collaborations with film composers as their conductor has yielded recorded scores for many films, while his own compositions have been performed by over two hundred orchestras across the United States. He has fulfilled commissions for countless organizations including Aperitif for the Debussy Trio. The piece is a buoyant work in a traditional A-B-A form, bound together by rhythmic permutations of a five-note motive, the first of which is heard at the onset of the piece. -

Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: a Performance Guide

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones May 2016 Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Fine Arts Commons, Music Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Repository Citation Vander Wyst, Erin Elizabeth, "Kimmo Hakola's Diamond Street and Loco: A Performance Guide" (2016). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 2754. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/9112202 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KIMMO HAKOLA’S DIAMOND STREET AND LOCO: A PERFORMANCE GUIDE By Erin Elizabeth Vander Wyst Bachelor of Fine Arts University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2007 Master of Music in Performance University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee 2009 -

NORTHERN STARS MUSIC from the NORDIC and BALTIC REGIONS NAXOS • MARCO POLO • ONDINE • PROPRIUS • SWEDISH SOCIETY • DACAPO Northern Stars

NORTHERN STARS MUSIC FROM THE NORDIC AND BALTIC REGIONS NAXOS • MARCO POLO • ONDINE • PROPRIUS • SWEDISH SOCIETY • DACAPO Northern Stars Often inspired by folk tradition, nature, landscape and a potent spirit of independence, the music of Scandinavia, Finland and the Baltic states is distinctive and varied, with each country’s music influenced by its neighbours, yet shaped and coloured by its individual heritage. Traveling composers such as Sweden’s Joseph Kraus introduced 18th and early 19th century classical trends from Germany and Italy, but with national identity gaining increasing importance as Romantic ideals took hold, influential and distinctive creative lines were soon established. The muscular strength of Carl Nielsen’s symphonies grew out of the Danish nationalist vigor shown by Friedrich Kuhlau and Niels Gade, extending to names such as Per Nørgård today. Gade was a teacher of Edvard Grieg, who owes his position as Norway’s leading composer, at least in part, to the country’s traditional folk music and the poignant lyricism of the Hardanger fiddle. The music of Finland is dominated by the rugged symphonies of Jean Sibelius, and his Finlandia ensured his status as an enduring national symbol. Sibelius successfully combined the lessons of Viennese romanticism with a strong Nordic character, and this pragmatic approach has generated numerous contemporary giants such as Aus Sallinen, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Kalevi Aho and Kaija Saariaho. Turbulent history in the Baltic States partially explains a conspicuous individualism amongst the region’s composers, few more so than with Arvo Pärt, whose work distils the strong Estonian vocal tradition into music of striking intensity and crystalline beauty.