UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY of HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY OF HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK PAUL STEFAN ML 41O M23S831 c.2 MUSI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Presented to the FACULTY OF Music LIBRARY by Estate of Robert A. Fenn GUSTAV MAHLER A Study of His Personality and tf^ork BY PAUL STEFAN TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN EY T. E. CLARK NEW YORK : G. SCHIRMER COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY G. SCHIRMER 24189 To OSKAR FRIED WHOSE GREAT PERFORMANCES OF MAHLER'S WORKS ARE SHINING POINTS IN BERLIN'S MUSICAL LIFE, AND ITS MUSICIANS' MOST SPLENDID REMEMBRANCES, THIS TRANSLATION IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BERLIN, Summer of 1912. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The present translation was undertaken by the writer some two years ago, on the appearance of the first German edition. Oskar Fried had made known to us in Berlin the overwhelming beauty of Mahler's music, and it was intended that the book should pave the way for Mahler in England. From his appearance there, we hoped that his genius as man and musi- cian would be recognised, and also that his example would put an end to the intolerable existing chaos in reproductive music- making, wherein every quack may succeed who is unscrupulous enough and wealthy enough to hold out until he becomes "popular." The English musician's prayer was: "God pre- serve Mozart and Beethoven until the right man comes," and this man would have been Mahler. Then came Mahler's death with such appalling suddenness for our youthful enthusiasm. Since that tragedy, "young" musicians suddenly find themselves a generation older, if only for the reason that the responsibility of continuing Mah- ler's ideals now rests upon their shoulders in dead earnest. -

Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: the Success of Arthur Honeggerâ•Žs Antigone in Vichy France

Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 7 2021 Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France Emma K. Schubart University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur Recommended Citation Schubart, Emma K. (2021) "Musical Hybridization and Political Contradiction: The Success of Arthur Honegger’s Antigone in Vichy France," Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 7 , Article 4. Retrieved from: https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/bjur/vol7/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Scholarship at Digital Commons @ Butler University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Butler Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Butler University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUTLER JOURNAL OF UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH, VOLUME 7 MUSICAL HYBRIDIZATION AND POLITICAL CONTRADICTION: THE SUCCESS OF ARTHUR HONEGGER’S ANTIGONE IN VICHY FRANCE EMMA K. SCHUBART, UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, CHAPEL HILL MENTOR: SHARON JAMES Abstract Arthur Honegger’s modernist opera Antigone appeared at the Paris Opéra in 1943, sixteen years after its unremarkable premiere in Brussels. The sudden Parisian success of the opera was extraordinary: the work was enthusiastically received by the French public, the Vichy collaborationist authorities, and the occupying Nazi officials. The improbable wartime triumph of Antigone can be explained by a unique confluence of compositional, political, and cultural realities. Honegger’s compositional hybridization of French and German musical traditions, as well as his opportunistic commercial motivations as a Swiss composer working in German-occupied France, certainly aided the success of the opera. -

Emily Jackson, Soprano Kathryn Piña, Soprano Mark Metcalf, Collaborative Pianist

Presents Emily Jackson, soprano Kathryn Piña, soprano Mark Metcalf, collaborative pianist Friday, April 23, 2021 ` 8:30 PM PepsiCo Recital Hall Program Cuatro Madrigales Amatorios Joaquín Rodrigo (1901-1999) 1. ¿Con qué la lavaré? 2. Vos me matásteis 3. ¿De dónde venís, amore? 4. De los álamos vengo, madre Ms. Piña Three Irish Folksong Settings John Corigliano (b. 1938) 1. The Salley Gardens 2. The Foggy Dew 3. She Moved Thro’The Fair Ms. Jackson Dr. Kristen Queen, flute Selections from 24 Canzoncine Isabella Colbran (1785-1845) Benché ti sia crudel T’intendo, si mio cor Professor Mallory McHenry, harp In uomini, in soldati from Cosi fan tutte W. A. Mozart (1756-1791) Ms. Piña Er Ist Gekommen in Sturm und Regen Clara Schumann Die Lorelei (1819-1896) O wär ich schön from Fidelio Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Ms. Jackson Of Memories and Dreams Patrick Vu (b. 1998) 1. Spring Heart Cleaning 2. Honey 3. Iris 4. On the Hillside *world premiere* Ms. Piña Patrick Vu, collaborative pianist Selections from Clarières dans le ciel Lili Boulanger (1893-1918) Parfois, je suis triste Nous nous aimerons tant Ms. Jackson Tarantelle Gabriel Fauré (1845-1924) Ms. Jackson and Ms. Piña This recital is given in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Bachelor’s Degree of Music with a vocal emphasis. Ms. Piña is a student of Dr. James Rodriguez and Emily Jackson is a student of Professor Angela Turner Wilson. The use of recording equipment or taking photographs is prohibited. Please silence all electronic devices including watches, pagers and phones. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

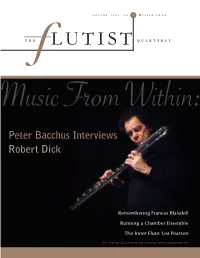

The Flutist Quarterly Volume Xxxv, N O

VOLUME XXXV , NO . 2 W INTER 2010 THE LUTI ST QUARTERLY Music From Within: Peter Bacchus Interviews Robert Dick Remembering Frances Blaisdell Running a Chamber Ensemble The Inner Flute: Lea Pearson THE OFFICIAL MAGAZINE OF THE NATIONAL FLUTE ASSOCIATION , INC :ME:G>:C8: I=: 7DA9 C:L =:69?D>CI ;GDB E:6GA 6 8ji 6WdkZ i]Z GZhi### I]Z cZl 8Vadg ^h EZVgaÉh bdhi gZhedch^kZ VcY ÓZm^WaZ ]ZVY_d^ci ZkZg XgZViZY# Djg XgV[ihbZc ^c ?VeVc ]VkZ YZh^\cZY V eZg[ZXi WaZcY d[ edlZg[ja idcZ! Z[[dgiaZhh Vgi^XjaVi^dc VcY ZmXZei^dcVa YncVb^X gVc\Z ^c dcZ ]ZVY_d^ci i]Vi ^h h^bean V _dn id eaVn# LZ ^ck^iZ ndj id ign EZVgaÉh cZl 8Vadg ]ZVY_d^ci VcY ZmeZg^ZcXZ V cZl aZkZa d[ jcbViX]ZY eZg[dgbVcXZ# EZVga 8dgedgVi^dc *). BZigdeaZm 9g^kZ CVh]k^aaZ! IC (,'&& -%%".),"(',* l l l # e Z V g a [ a j i Z h # X d b Table of CONTENTS THE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXV, N O. 2 W INTER 2010 DEPARTMENTS 5 From the Chair 51 Notes from Around the World 7 From the Editor 53 From the Program Chair 10 High Notes 54 New Products 56 Reviews 14 Flute Shots 64 NFA Office, Coordinators, 39 The Inner Flute Committee Chairs 47 Across the Miles 66 Index of Advertisers 16 FEATURES 16 Music From Within: An Interview with Robert Dick by Peter Bacchus This year the composer/musician/teacher celebrates his 60th birthday. Here he discusses his training and the nature of pedagogy and improvisation with composer and flutist Peter Bacchus. -

50Th Annual Concerto Concert

SCHOOL OF ART | COLLEGE OF MUSICAL ARTS | CREATIVE WRITING | THEATRE & FILM BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY 50th a n n u a l c o n c e r t o concert BOWLING GREEN STATE UNIVERSITY Summer Music Institute 2017 bgsu.edu/SMI featuring the SESSION ONE - June 11-16 bowling g r e e n Double Reed Strings philharmonia SESSION TWO - June 18-23 emily freeman brown, conductor Brass Recording Vocal Arts SESSION THREE - June 25-30 Musical Theatre saturday, february 25 Saxophone 2017 REGISTRATION OPENS FEBRUARY 1ST 8:00 p.m. For more information, visit BGSU.edu/SMI kobacker hall BELONG. STAND OUT. GO FAR. CHANGING LIVES FOR THE WORLD.TM congratulations to the w i n n e r s personnel of the 2016-2 017 Violin I Bass Trombone competition in music performance Alexandria Midcalf** Nicholas R. Young* Kyle McConnell* Brandi Main** Lindsay W. Diesing James Foster Teresa Bellamy** Adam Behrendt Jef Hlutke, bass Mary Solomon Stephen J. Wolf Morgan Decker, guest Ling Na Kao Cameron M. Morrissey Kurtis Parker Tuba Jianda Bai Flute/piccolo Diego Flores La Le Du Alaina Clarice* undergraduate - performance Nia Dewberry Samantha Tartamella Percussion/ Timpani Anna Eyink Michelle Whitmore Scott Charvet* Stephen Dubetz, clarinet Keisuke Kimura Jerin Fuller+ Elijah T omas Oboe/Cor Anglais Zachary Green+ Michelle Whitmore, flute Jana Zilova* Febe Harmon Violin II T omas Morris David Hirschfeld+ Honorable Mention: Samantha Tartamella, flute Sophia Schmitz Mayuri Yoshii Erin Reddick+ Bethany Holt Anthony Af ul Felix Reyes Zi-Ling Heah Jamie Maginnis Clarinet/Bass clarinet/ Harp graduate - performance Xiangyi Liu E-f at clarinet Michaela Natal Lindsay Watkins Lucas Gianini** Keyboard Kenneth Cox, flute Emily Topilow Hayden Giesseman Paul Shen Kyle J. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

Honegger Pastorale D’Été Symphony No

HONEGGER PASTORALE D’ÉTÉ SYMPHONY NO. 4 UNE CANTATE DE NOËL VLADIMIR JUROWSKI conductor CHRISTOPHER MALTMAN baritone LONDON PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA and CHOIR NEW LONDON CHILDREN’S CHOIR 0058 Honegger booklet.indd 1 8/23/2011 10:24:50 AM HONEGGER PASTORALE D’ÉTÉ (SUMMER PASTORAL) Today the Swiss-born composer Arthur of birdsong on woodwind place Honegger Honegger is often remembered as a member more amongst the 19th-century French of ‘Les Six’ – that embodiment of 1920s landscape painters than les enfants terribles. Parisian modernist chic in music. How unjust. From this, Pastorale d’été builds to a rapturous It is true that for a while Honegger shared climax then returns – via a middle section some of the views of true ‘Sixists’ like Francis that sometimes echoes the pastoral Vaughan Poulenc and Darius Milhaud, particularly Williams – to the lazy, summery motion of when they were students together at the Paris the opening. Conservatoire. But even from the start he Stephen Johnson could not share his friends’ enthusiasm for the eccentric prophet of minimalism and Dadaism, Eric Satie, and he grew increasingly irritated with the group’s self-appointed literary SYMPHONY NO. 4 apologist, Jean Cocteau. It was soon clear that, despite the dissonant, metallic futurism of By the time Honegger came to write his Fourth works like Pacific 231 (1923), Honegger had Symphony in 1946, he was barely recognizable more respect for traditional forms and for as the former fellow traveller of the wilfully romantic expression than his friends could provocative Les Six. He had moved away from accept. Poulenc and Milhaud both dismissed any desire to shock or scandalize audiences: Honegger’s magnificent ‘dramatic psalm’ Le Roi instead, like Mozart, he strove ‘to write music David (‘King David’, 1923) as over-conventional. -

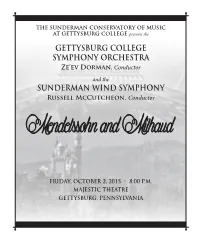

View Concert Program

THE SUNDERMAN CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC AT GETTYSBURG COLLEGE presents the GETTYSBURG COLLEGE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Ze’ev Dorman, Conductor and the SUNDERMAN WIND SYMPHONY Russell McCutcheon, Conductor Friday, OctOber 2, 2015 • 8:00 p.m. MAJESTIC THEATRE GETTYSBURG, PENNSYLVANIA blank Program SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ZE’EV DORMAN, CONDUCTOR Symphony No.9 in C Major ............................................................................................Felix Mendelssohn -Bartholdy (1809-1847) I. Grave, Allegro II. Andante III. Scherzo IV. Allegro vivace — Intermission — WIND SYMPHONY Russell McCutcheon, Conductor Fanfare from “La Péri” ............................................................................................................... Paul Dukas (1865 – 1935) Asclepius .......................................................................................................................Michael Daugherty (b. 1954) Sechs Tänze, Op. 71 .................................................................................................................. Rolf Rudin (b. 1961) I. Breit schreitend II. Very fast III. Giocoso IV. Breit und wuchtig V. Con eleganza VI. Molto vivace Suite Française ....................................................................................................................Darius Milhaud (1892 – 1974) I. Normandy II. Brittany III. Île-de-France IV. Alsace-Lorraine V. Provence Program Notes Tonight’s program alternates between Germany and France, with a diversion to the United States in-between. The Symphony Orchestra