The Sorcerer's Apprentice Paul Dukas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY of HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK

IGUSTAV MAHLER Ik STUDY OF HIS PERSONALITY 6 WORK PAUL STEFAN ML 41O M23S831 c.2 MUSI UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO Presented to the FACULTY OF Music LIBRARY by Estate of Robert A. Fenn GUSTAV MAHLER A Study of His Personality and tf^ork BY PAUL STEFAN TRANSLATED FROM THE GERMAN EY T. E. CLARK NEW YORK : G. SCHIRMER COPYRIGHT, 1913, BY G. SCHIRMER 24189 To OSKAR FRIED WHOSE GREAT PERFORMANCES OF MAHLER'S WORKS ARE SHINING POINTS IN BERLIN'S MUSICAL LIFE, AND ITS MUSICIANS' MOST SPLENDID REMEMBRANCES, THIS TRANSLATION IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BERLIN, Summer of 1912. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The present translation was undertaken by the writer some two years ago, on the appearance of the first German edition. Oskar Fried had made known to us in Berlin the overwhelming beauty of Mahler's music, and it was intended that the book should pave the way for Mahler in England. From his appearance there, we hoped that his genius as man and musi- cian would be recognised, and also that his example would put an end to the intolerable existing chaos in reproductive music- making, wherein every quack may succeed who is unscrupulous enough and wealthy enough to hold out until he becomes "popular." The English musician's prayer was: "God pre- serve Mozart and Beethoven until the right man comes," and this man would have been Mahler. Then came Mahler's death with such appalling suddenness for our youthful enthusiasm. Since that tragedy, "young" musicians suddenly find themselves a generation older, if only for the reason that the responsibility of continuing Mah- ler's ideals now rests upon their shoulders in dead earnest. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Music as Representational Art Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1vv9t9pz Author Walker, Daniel Publication Date 2014 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Daniel Walker 2014 © Copyright by Daniel Walker 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Volume I Music as Representational Art Volume II Awakening by Daniel Walker Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair There are two volumes to this dissertation; the first is a monograph, and the second is a musical composition, both of which are described below. Volume I Music is a language that can be used to express a vast range of ideas and emotions. It has been part of the human experience since before recorded history, and has established a unique place in our consciousness, and in our hearts by expressing that which words alone cannot express. ii My individual interest in the musical language is its use in telling stories, and in particular in the form of composition referred to as program music; music that tells a story on its own without the aid of images, dance or text. The topic of this dissertation follows this line of interest with specific focus on the compositional techniques and creative approach that divide program music across a representational spectrum from literal to abstract. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2017). Michael Finnissy - The Piano Music (10 and 11) - Brochure from Conference 'Bright Futures, Dark Pasts'. This is the other version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17523/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] BRIGHT FUTURES, DARK PASTS Michael Finnissy at 70 Conference at City, University of London January 19th-20th 2017 Bright Futures, Dark Pasts Michael Finnissy at 70 After over twenty-five years sustained engagement with the music of Michael Finnissy, it is my great pleasure finally to be able to convene a conference on his work. This event should help to stimulate active dialogue between composers, performers and musicologists with an interest in Finnissy’s work, all from distinct perspectives. It is almost twenty years since the publication of Uncommon Ground: The Music of Michael Finnissy (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1998). -

Sounding Nostalgia in Post-World War I Paris

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Tristan Paré-Morin University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Recommended Citation Paré-Morin, Tristan, "Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3399. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3399 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sounding Nostalgia In Post-World War I Paris Abstract In the years that immediately followed the Armistice of November 11, 1918, Paris was at a turning point in its history: the aftermath of the Great War overlapped with the early stages of what is commonly perceived as a decade of rejuvenation. This transitional period was marked by tension between the preservation (and reconstruction) of a certain prewar heritage and the negation of that heritage through a series of social and cultural innovations. In this dissertation, I examine the intricate role that nostalgia played across various conflicting experiences of sound and music in the cultural institutions and popular media of the city of Paris during that transition to peace, around 1919-1920. I show how artists understood nostalgia as an affective concept and how they employed it as a creative resource that served multiple personal, social, cultural, and national functions. Rather than using the term “nostalgia” as a mere diagnosis of temporal longing, I revert to the capricious definitions of the early twentieth century in order to propose a notion of nostalgia as a set of interconnected forms of longing. -

Paris, 1918-45

un :al Chapter II a nd or Paris , 1918-45 ,-e ed MARK D EVOTO l.S. as es. 21 March 1918 was the first day of spring. T o celebrate it, the German he army, hoping to break a stalemate that had lasted more than three tat years, attacked along the western front in Flanders, pushing back the nv allied armies within a few days to a point where Paris was within reach an oflong-range cannon. When Claude Debussy, who died on 25 M arch, was buried three days later in the Pere-Laehaise Cemetery in Paris, nobody lingered for eulogies. The critic Louis Laloy wrote some years later: B. Th<' sky was overcast. There was a rumbling in the distance. \Vas it a storm, the explosion of a shell, or the guns atrhe front? Along the wide avenues the only traffic consisted of militarr trucks; people on the pavements pressed ahead hurriedly ... The shopkeepers questioned each other at their doors and glanced at the streamers on the wreaths. 'II parait que c'ctait un musicicn,' they said. 1 Fortified by the surrender of the Russians on the eastern front, the spring offensive of 1918 in France was the last and most desperate gamble of the German empire-and it almost succeeded. But its failure was decisive by late summer, and the greatest war in history was over by November, leaving in its wake a continent transformed by social lb\ convulsion, economic ruin and a devastation of human spirit. The four-year struggle had exhausted not only armies but whole civiliza tions. -

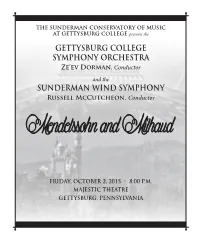

View Concert Program

THE SUNDERMAN CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC AT GETTYSBURG COLLEGE presents the GETTYSBURG COLLEGE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Ze’ev Dorman, Conductor and the SUNDERMAN WIND SYMPHONY Russell McCutcheon, Conductor Friday, OctOber 2, 2015 • 8:00 p.m. MAJESTIC THEATRE GETTYSBURG, PENNSYLVANIA blank Program SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ZE’EV DORMAN, CONDUCTOR Symphony No.9 in C Major ............................................................................................Felix Mendelssohn -Bartholdy (1809-1847) I. Grave, Allegro II. Andante III. Scherzo IV. Allegro vivace — Intermission — WIND SYMPHONY Russell McCutcheon, Conductor Fanfare from “La Péri” ............................................................................................................... Paul Dukas (1865 – 1935) Asclepius .......................................................................................................................Michael Daugherty (b. 1954) Sechs Tänze, Op. 71 .................................................................................................................. Rolf Rudin (b. 1961) I. Breit schreitend II. Very fast III. Giocoso IV. Breit und wuchtig V. Con eleganza VI. Molto vivace Suite Française ....................................................................................................................Darius Milhaud (1892 – 1974) I. Normandy II. Brittany III. Île-de-France IV. Alsace-Lorraine V. Provence Program Notes Tonight’s program alternates between Germany and France, with a diversion to the United States in-between. The Symphony Orchestra -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 096 203 SO 007 735 AUTHOR Pearl, Jesse; Carter, Raymond TITLE Music Listening--The Classical Period (1720-1815), Music: 5635.793. INSTITUTION Dade County Public Schools, Miami, Fla. PUB DATE 72 NOTE 42p.; An Authorized Course of Instruction for the Quinmester Program; SO 007 734-737 are related documents PS PRICE MP-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Aesthetic Education; Course Content; Course Objectives; Curriculum Guides; *Listening Habits; *Music Appreciation; *Music Education; Mucic Techniques; Opera; Secondary Grades; Teaching Techniques; *Vocal Music IDENTIFIERS Classical Period; Instrumental Music; *Quinmester Program ABSTRACT This 9-week, Quinmester course of study is designed to teach the principal types of vocal, instrumental, and operatic compositions of the classical period through listening to the styles of different composers and acquiring recognition of their works, as well as through developing fastidious listening habits. The course is intended for those interested in music history or those who have participated in the performing arts. Course objectives in listening and musicianship are listed. Course content is delineated for use by the instructor according to historical background, musical characteristics, instrumental music, 18th century opera, and contributions of the great masters of the period. Seven units are provided with suggested music for class singing. resources for student and teacher, and suggestions for assessment. (JH) US DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH EDUCATION I MIME NATIONAL INSTITUTE -

June 29 to July 5.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES June 29 - July 5, 2020 PLAY DATE : Mon, 06/29/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto 6:11 AM Johann Nepomuk Hummel Serenade for Winds 6:31 AM Johan Helmich Roman Concerto for Violin and Strings 6:46 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Symphony 7:02 AM Johann Georg Pisendel Concerto forViolin,Oboes,Horns & Strings 7:16 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Sonata No. 32 7:30 AM Jean-Marie Leclair Violin Concerto 7:48 AM Antonio Salieri La Veneziana (Chamber Symphony) 8:02 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Mensa sonora, Part III 8:12 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 34 8:36 AM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. 3 9:05 AM Leroy Anderson Concerto for piano and orchestra 9:25 AM Arthur Foote Piano Quartet 9:54 AM Leroy Anderson Syncopated Clock 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem: Communio: Lux aeterna 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Sonata No. 21, K 304/300c 10:23 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart DON GIOVANNI Selections 10:37 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata for 2 pianos 10:59 AM Felix Mendelssohn String Quartet No. 3 11:36 AM Mauro Giuliani Guitar Concerto No. 1 12:00 PM Danny Elfman A Brass Thing 12:10 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Schwärmereien Concert Waltz 12:23 PM Franz Liszt Un Sospiro (A Sigh) 12:32 PM George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue 12:48 PM John Philip Sousa Our Flirtations 1:00 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony No. 6 1:43 PM Michael Kurek Sonata for Viola and Harp 2:01 PM Paul Dukas La plainte, au loin, du faune...(The 2:07 PM Leos Janacek Sinfonietta 2:33 PM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. -

Tuesday Playlist

October 1, 2019: (Full-page version) Close Window “If we understood the world, we would realise that there is a logic of harmony underlying its manifold apparent dissonances.” — Jean Sibelius Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, 00:01 Buy Now! Wagner Overture ~ Rienzi Basel Symphony/Jordan Erato 88015 326965880152 Awake! 00:14 Buy Now! Beethoven String Quartet No. 11 in F minor, Op. 95 "Serioso" Moscow Soloists/Bashmet RCA Red Seal 60988 090266098828 00:38 Buy Now! Dvorak Sonatina in G, Op. 100 Galway/Moll RCA Red Seal 7802 078635780222 01:00 Buy Now! Dukas Sorcerer's Apprentice London Symphony/Mackerras Allegro 1022 723722336126 01:11 Buy Now! Albéniz Iberia, Book 1 Lang Lang Sony 71901 886977160124 01:33 Buy Now! Delius Violin Concerto Menuhin/Royal Philharmonic/Davies EMI Classics 64725 077776472522 02:01 Buy Now! Vivaldi Cello Concerto in C minor, RV 401 Dieltiens/Ensemble Explorations Harmonia Mundi 901655 794881441525 02:14 Buy Now! Schubert Serenade, D. 957 No. 4 Sly/Britton Analekta 2 9999 774204999926 02:18 Buy Now! Beethoven Septet in E flat, Op. 20 Members of New Vienna Octet London 414 576 028941457622 03:03 Buy Now! Mozart Piano Sonata No. 13 in B flat, K. 333 Vladimir Horowitz DG 423 287 02894232872 03:30 Buy Now! Strauss Jr. Accelerations Boston Pops/Fiedler RCA 6213 07863561232 03:40 Buy Now! Bach Cello Suite No. 1 in G, BWV 1007 Yo-Yo Ma Sony Classical 63203 074646320327 04:00 Buy Now! Debussy Two Arabesques Stoltzman/Allen RCA 60198 090266019823 04:09 Buy Now! Still Poem for Orchestra Fort Smith Symphony/Jeter Naxos 8.559603 636943960325 04:20 Buy Now! Elgar Piano Quintet in A minor, Op. -

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906)

Paul Dukas: Villanelle for Horn and Orchestra (1906) Paul Dukas (1865-1935) was a French composer, critic, scholar and teacher. A studious man, of retiring personality, he was intensely self-critical, and as a perfectionist he abandoned and destroyed many of his compositions. His best known work is the orchestral piece The Sorcerer's Apprentice (L'apprenti sorcier), the fame of which became a matter of irritation to Dukas. In 2011, the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians observed, "The popularity of L'apprenti sorcier and the exhilarating film version of it in Disney's Fantasia possibly hindered a fuller understanding of Dukas, as that single work is far better known than its composer." Among his other surviving works are the opera Ariane et Barbe-bleue (Ariadne and Bluebeard, 1897, later championed by Toscanini and Beecham), a symphony (1896), two substantial works for solo piano (Sonata, 1901, and Variations, 1902) and a sumptuous oriental ballet La Péri (1912). Described by the composer as a "poème dansé" it depicts a young Persian prince who travels to the ends of the Earth in a quest to find the lotus flower of immortality, coming across its guardian, the Péri (fairy). Because of the very quiet opening pages of the ballet score, the composer added a brief "Fanfare pour précéder La Peri" which gave the typically noisy audiences of the day time to settle in their seats before the work proper began. Today the prelude is a favorite among orchestral brass sections. At a time when French musicians were divided into conservative and progressive factions, Dukas adhered to neither but retained the admiration of both. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven (1770-1827)

21M011 (spring, 2006) Ellen T. Harris Lecture VII Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Like Monteverdi, who bridges the Renaissance and the Baroque, Beethoven stands between two eras, not fully encompassed by either. He inherited the Classical style through Mozart and Haydn, and this is represented in works from what is typically called his “first period” (to about 1800), during which time Beethoven performed actively as a virtuoso pianist. The “middle period” (about 1800 to 1818) saw Beethoven break through the classical templates as he wrestled with his increasing deafness, the growing inability to perform or conduct, and his disillusion with Napoleon, whom he had considered a hero of the French Revolution until Napoleon declared himself Emperor in 1804. 1802: Heiligenstadt Testament depicts Beethoven’s desolation over his deafness; 1803: composition of the 3rd Symphony, originally titled Bonaparte, but changed to Eroica after, 1804: Napoleon declares himself Emperor 1808: 5th Symphony in C minor, Op. 67 From Beethoven’s middle period come the works most often associated with Beethoven and with what is known of his personality: forceful, uncompromising, angry, willful, suffering, but overcoming extraordinary personal hardship, all of which traits are read into his music. The Romantic cult of the individual who represents himself in his music and of the genius who suffers for his art begins here with Beethoven. Beethoven’s “late period” (1818 to his death [1827]) becomes more introspective and abstract, as Beethoven’s deafness increasingly forces him to retreat into himself. Although the 9th Symphony dates from these years, it is the only symphony to do so, and, in many respects, is a throwback to the middle period.