Behavioural and Neural Responses to Facial Disfigurement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Bond a 50 The

JAMES BOND: SIGNIFYING CHANGING IDENTITY THROUGH THE COLD WAR AND BEYOND By Christina A. Clopton Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Arts Supervisor: Professor Alexander Astrov CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 Word Count: 12,928 Abstract The Constructivist paradigm of International Relations (IR) theory has provided for an ‘aesthetic turn’ in IR. This turn can be applied to popular culture in order to theorize about the international system. Using the case study of the James Bond film series, this paper investigates the continuing relevancy of the espionage series through the Cold War and beyond in order to reveal new information about the nature of the international political system. Using the concept of the ‘empty signifier,’ this work establishes the shifting identity of James Bond in relation to four thematic icons in the films: the villains, locations, women and technology and their relation to the international political setting over the last 50 years of the films. Bond’s changing identity throughout the series reveals an increasingly globalized society that gives prominence to David Chandler’s theory about ‘empire in denial,’ in which Western states are ever more reluctant to take responsibility for their intervention abroad. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Professor Alexander Astrov for taking a chance with me on this project and guiding me through this difficult process. I would also like to acknowledge the constant support and encouragement from my IRES colleagues through the last year. -

Things Are Not Enough Bond, Stiegler, and Technics

Things Are Not Enough Bond, Stiegler, and Technics CLAUS-ULRICH VIOL Discussions of Bond’s relationship with technology frequently centre around the objects he uses, the things he has at his disposal: what make is the car, what products have been placed in the flm, are the flm’s technical inventions realistic, visionary even !his can be observed in cinema foyers, fan circles, the media, as well as academia. #$en these discussions take an admiring turn, with commentators daz%led by the technological foresight of the flmic ideas; ' quite ofen too, especially in academic circles, views tend to be critical, connecting Bond’s technological overkill to some compensatory need in the character, seeing the technological objects as (props) that would and should not have to be ' *ee, for instance, publications like The Science of James Bond by Gresh and ,einberg -.//01, who set out to provide an “informative look at the real2world achievements and brilliant imaginations) behind the Bond gadgets, asking how realistic or “fant2 astic) the adventures and the equipment are and promising to thus probe into (the limits of science, the laws of nature and the future of technology” -back cover1" 3arker’s similar Death Rays, Jet Packs, Stunts and Supercars -.//41 includes discussions of the physics behind the action scenes -like stunts and chases1, but there remains a heavy preponderance of (ama%ing devices), (gadgets and gi%mos), “incredible cars), (reactors) and (guns) -v2vi1" ,eb pages and articles about (Bond Gadgets that 5ave Become 6eal), “Bond Gadgets 7ou 8an 9ctually Buy”, “Bond Gadgets that 8ould ,ork in 6eal :ife) and the like are legion. -

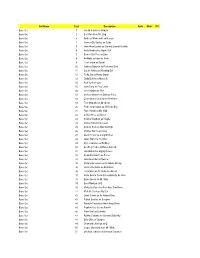

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

International Spy Museum

International Spy Museum Searchable Master Script, includes all sections and areas Area Location, ID, Description Labels, captions, and other explanatory text Area 1 – Museum Lobby M1.0.0.0 ΚΑΤΆΣΚΟΠΟΣ SPY SPION SPIJUN İSPİYON SZPIEG SPIA SPION ESPION ESPÍA ШПИОН Language of Espionage, printed on SCHPION MAJASUSI windows around entrance doors P1.1.0.0 Visitor Mission Statement For Your Eyes Only For Your Eyes Only Entry beyond this point is on a need-to-know basis. Who needs to know? All who would understand the world. All who would glimpse the unseen hands that touch our lives. You will learn the secrets of tradecraft – the tools and techniques that influence battles and sway governments. You will uncover extraordinary stories hidden behind the headlines. You will meet men and women living by their wits, lurking in the shadows of world affairs. More important, however, are the people you will not meet. The most successful spies are the unknown spies who remain undetected. Our task is to judge their craft, not their politics – their skill, not their loyalty. Our mission is to understand these daring professionals and their fallen comrades, to recognize their ingenuity and imagination. Our goal is to see past their maze of mirrors and deception to understand their world of intrigue. Intelligence facts written on glass How old is spying? First record of spying: 1800 BC, clay tablet from Hammurabi regarding his spies. panel on left side of lobby First manual on spy tactics written: Over 2,000 years ago, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. 6 video screens behind glass panel with facts and images. -

Behavioural and Neural Responses to Facial Disfigurement

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Behavioural and Neural Responses to Facial Disfgurement Franziska Hartung 1,2, Anja Jamrozik 1, Miriam E. Rosen1, Geofrey Aguirre 1, David B. Sarwer 3 & Anjan Chatterjee 1,2 Received: 30 October 2018 Faces are among the most salient and relevant visual and social stimuli that humans encounter. Accepted: 15 May 2019 Attractive faces are associated with positive character traits and social skills and automatically evoke Published: xx xx xxxx larger neural responses than faces of average attractiveness in ventral occipito-temporal cortical areas. Little is known about the behavioral and neural responses to disfgured faces. In two experiments, we tested the hypotheses that people harbor a disfgured is bad bias and that ventral visual neural responses, known to be amplifed to attractive faces, represent an attentional efect to facial salience rather than to their rewarding properties. In our behavioral study (N = 79), we confrmed the existence of an implicit ‘disfgured is bad’ bias. In our functional MRI experiment (N = 31), neural responses to photographs of disfgured faces before treatment evoked greater neural responses within ventral occipito-temporal cortex and diminished responses within anterior cingulate cortex. The occipito- temporal activity supports the hypothesis that these areas are sensitive to attentional, rather than reward properties of faces. The relative deactivation in anterior cingulate cortex, informed by our behavioral study, may refect suppressed empathy and social cognition and indicate evidence of a possible neural mechanism underlying dehumanization. Physical appearance has a profound impact on a person’s life. Beautiful people are preferred and enjoy many advantages compared to average-looking people1. -

The Man with the Golden Eye: Designing the James Bond Films Free Download

THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN EYE: DESIGNING THE JAMES BOND FILMS FREE DOWNLOAD Peter Lamont,Marcus Hearn | 176 pages | 22 Nov 2016 | Signum Books (Imprint of Flashpoint Media Ltd) | 9780995519114 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom 007 James Bond Golden Eye 1995 Part 01 As with nuclear missiles, two keys are used so that no single person can launch. News, advice and insights for the most interesting man in the room. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. James Bond Sean Bean The episode first aired February 16, Edit Did You Know? James Bond Sean Bean The opening is fine. Highly recommended Richly illustrated with The Man with the Golden Eye: Designing the James Bond Films of rare and previously unseen stills, this revealing memoir takes the reader on a unique journey through five decades of filmmaking. I'm a hard-core James Bond fan. There are no discussion topics on this book yet. Bottom of the Barrell. January 6, Hardcoverpages. James Bond woos a mob boss' daughter and goes undercover to uncover the true reason for Ernst Stavro Blofeld's allergy research in the Swiss Alps involving beautiful women from around the world. James Bond is sent to stop a diabolically brilliant heroin magnate armed with a complex organisation and a reliable psychic tarot card reader. Download as PDF Printable version. The Guardian UK. James Bond action film the best one that was ever made. Jim Calzacorto added it Apr 25, Movies Seen This Year Admiral Chuck Farrell Constantine Gregory Den of The Man with the Golden Eye: Designing the James Bond Films. -

Reading Bond Films Through the Lens of “Religion” Discourse of “The West and the Rest”

Teemu Taira Reading Bond Films through the Lens of “Religion” Discourse of “the West and the Rest” ABSTRACT “Religion” has been absent from the study of James Bond films. Similarly, James Bond has been absent from studies on religion and popular culture. This article aims to fill the gap by examining 25 Bond films through the lens of “religion”. The analysis suggests that there are a number of references to “religion” in Bond films, although “religion” is typi- cally not a main topic of the films. Furthermore, there is a detectable pattern in the films: “religion” belongs primarily to what is regarded as not belonging to “the West” and “the West” is considered modern, developed and rational as opposed to the backward, exotic and “religious” “Rest”. When “religion” appears in “the West”, it is seen positively if it is related to Christianity and confined to the private sphere and to the rites of passage. In this sense, representations of “religion” in Bond films contribute to what Stuart Hall named the discourse of “the West and the Rest”, thus playing a role in the maintenance of the idea of “the West”. This will be demonstrated by focusing on four thematic ex- amples from the films: mythical villains, imperialist attitude to “religion” outside “the West”, “religion” central in the plot (voodoo and tarot), Christianity in “the West”. This article also provides grounds for suggesting that reading Bond films through the lens of “religion” contributes to both Bond studies and studies on religion and popular culture. KEYWORDS Religion, Film, James Bond, Popular Culture, the West, Discourse, Representation, Myth, Colonialism, Imperialism, Christianity, Secular, Rationality BIOGRAPHY Teemu Taira is Senior Lecturer in Study of Religion, University of Helsinki, and Docent in Study of Religion, University of Turku. -

The Quantum of Missus Guide to the James Bond Films

THE QUANTUM OF MISSUS GUIDE TO THE JAMES BOND FILMS Bond : Barry Nelson as CIA agent “card sense” Jimmy Bond Villains : Le Chiffre (Peter Lorre) Allies : Valerie Mathis Clarence Leiter Locations: France Villain’s Plot: Le Chiffre intends to win at baccarat in order to make money for the USSR The one with: black and white TV show Bond : Sean Connery Villains : Dr. No Allies : Honey Ryder (Ursula Andress) Felix Leiter (Jack Lord) M (Bernard Lee) Miss Moneypenny (Lois Maxwell) Sylvia Trench Gadgets: Geiger counter Locations: Jamaica Villain’s Plot: Jamming US and Soviet rocket controls and communications on behalf of SPECTRE and to get revenge for his seeking employment with both superpowers being declined. Theme song : James Bond Theme, Three Blind Mice, Under The Mango Tree The one with: the woman in the white bikini coming out of the sea; Bond being a “very nerrr-vus passin-jurr” Bond : Sean Connery Villains : Ernst Stavro Blofeld (unseen) Rosa Klebb “Red” Grant Allies: Tatiana Romanova Kerim Bey M Major Boothroyd/Q (Desmond Llewelyn) Miss Moneypenny Gadgets: Briefcase containing gold sovereigns, knife, exploding capabilities, compact rifle and ammunition Locations: Istanbul, Venice Villain’s plot: Recently defected SMERSH agent Rosa Klebb is charged by Blofeld, head of SPECTRE, with carrying out a plot to embarrass the Russians and the British by (a) stealing a coding machine from the Russians and (b) filming Bond having sex with the Russian cipher clerk who, believing she is working under Moscow’s orders, will entice him to Istanbul -

Of Migrants and Men: Networks and Nations in the Millennial Bond Text

Of Migrants and Men: Networks and Nations in the Millennial Bond Text EDWARD P. COMENTALE AND STEPHEN WATT “In this image [heimat] we, the countless million of migrants (whether guest workers, exiles, refugees, or intellectuals…) recognize ourselves not as outsiders but as vanguards of the future !ll we nomads share in the colla"se of settledness # - %ilém 'lusser, The Freedom of the Migrant: Objections to Nationalism (())*) “+he text is a fetish object and this fetish desires me +he text chooses me, b- a whole dis$ "osition of invisible screens, selective ba.es/ vocabular-, references, readability, etc.0 and, lost in the midst of a text. there is alwa-s the other, the author # - 1oland 2arthes, The Pleasure of the Text (3455) “Bond ceases to be a subject for "s-chiatr- and remains at the most a "h-siological object (exce"t for a return to "s-chic diseases in the last, unt-"ical novel in the series, The Man with the Golden Gun)…In the last "ages of Casino Royale, 'leming,in fact, renounces all "s-$ chology as the motive of narrative and decides to transfer characters and situations to the level of an objective structural strategy # - 7mberto Eco, The Role of the Reader: !xplorations in the #emiotics of Texts (3454) +hese three excer"ts suggest the intimatel- connected aims of this article on the evolution of 9ames 2ond in both contemporar- cinema and, more broadl-, the twent-$:rst centur- +hese aims, after %ilém 'lusser, might be termed assess$ ments of heimat construed not onl- as homes “encased in m-sti:cation# and Edward P. -

Taira Teemu Reading Bond Films Through the Lens of Religion

Teemu Taira Reading Bond Films through the Lens of “Religion” Discourse of “the West and the Rest” ABSTRACT “Religion” has been absent from the study of James Bond films. Similarly, James Bond has been absent from studies on religion and popular culture. This article aims to fill the gap by examining 25 Bond films through the lens of “religion”. The analysis suggests that there are a number of references to “religion” in Bond films, although “religion” is typi- cally not a main topic of the films. Furthermore, there is a detectable pattern in the films: “religion” belongs primarily to what is regarded as not belonging to “the West” and “the West” is considered modern, developed and rational as opposed to the backward, exotic and “religious” “Rest”. When “religion” appears in “the West”, it is seen positively if it is related to Christianity and confined to the private sphere and to the rites of passage. In this sense, representations of “religion” in Bond films contribute to what Stuart Hall named the discourse of “the West and the Rest”, thus playing a role in the maintenance of the idea of “the West”. This will be demonstrated by focusing on four thematic ex- amples from the films: mythical villains, imperialist attitude to “religion” outside “the West”, “religion” central in the plot (voodoo and tarot), Christianity in “the West”. This article also provides grounds for suggesting that reading Bond films through the lens of “religion” contributes to both Bond studies and studies on religion and popular culture. KEYWORDS Religion, Film, James Bond, Popular Culture, the West, Discourse, Representation, Myth, Colonialism, Imperialism, Christianity, Secular, Rationality BIOGRAPHY Teemu Taira is Senior Lecturer in Study of Religion, University of Helsinki, and Docent in Study of Religion, University of Turku. -

James Bond Deck Building Game

® A JAMES BOND DECK BUILDING GAME RULE BOOK Ages 14+ “The name’s Bond. James Bond.” new Heroes you recruited. This way Legendary ®: James Bond 007 also your deck gets stronger and stronger Your First Game introduces two new card types: over time. Build up enough power, For your first game we suggest you Gadgets and Missions. Overview and you can defeat the Mastermind! play the movie Goldfinger. Follow Welcome to Legendary ®: But be careful: If the players fail too the setup rules on the following Gadgets work just like Bystanders James Bond 007! In this game you many Missions, the Mastermind page, using the specific card stacks in previous games — Villains can can play four classic Bond movies: wins the game! listed there. After your first game, acquire them and escape with them Goldfinger, The Man With The you can have fun playing the to help the Mastermind’s chances. Golden Gun, GoldenEye, or other three movies included in the Casino Royale. Can you foil How to Win game: The Man With The Golden Missions are tasks for you to Operation: Grand Slam and end Players must attack the Mastermind Gun, GoldenEye, and Casino Royale. complete. In most ways they work Goldfinger’s plot to contaminate the successfully four times. If they do Each movie uses different Heroes, just like a Villain — they enter gold supply of the United States? this, then the Mastermind is beaten Villains, Missions, Masterminds, and On Assignment, they can acquire Do you have the steely nerve to best once and for all, and all the players Schemes. -

Goodbye Mister Bond: 007'S Critical Advocacy for Feminism & Modernism

Goodbye Mister Bond: 007’s critical advocacy for feminism & modernism Dr. Harriet Harriss Royal College of Art, UK INTRODUCTION It’s not just villains that are fond of saying, “goodbye mister Bond”. Any viewer mindful of prejudice is likely to have wished that he - or rather his casually misogynistic attitudes to women – could get killed off on occasion, too. And yet, could James Bond be considered to be both a feminist and modernist advocate? If not, then why would the author - an architect and a feminist - find the way in which both women and modernist buildings are represented in all 24 Bond films politically affirming and even professionally inspiring - as opposed to simply sexist or oppressive (Funnell, 2011)? In the spirit of auto- ethnographic curiosity (Chang, 2008), this paper considers whether the way in which Bond films represent both women and modernist architecture amounts to negative stereotyping, or if they offer instead a critique of their mutually problematised status within society. RISKY WOMEN Whilst author Ian Fleming’s James Bond character has long been vilified as a sexist, the cinematic franchise continues smash box office records (Ashton, 2015). But what is it about the Bond franchise that women find appealing?. More recent iterations have seen the Bond character manifest “endearing cracks” and “weaknesses” (Cox, 2015), not unlike a concrete edifice, gently degrading. Previously it has been argued that the Bond series strategically incorporates second-wave feminist discourses, not as a means to alter Bond’s attitude to women, but rather, to alter the attitudes of the women around him to Bond (Chapman, 2000).