The New Q, Masculinity and the Craig Era Bond Films Claire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Bond a 50 The

JAMES BOND: SIGNIFYING CHANGING IDENTITY THROUGH THE COLD WAR AND BEYOND By Christina A. Clopton Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Arts Supervisor: Professor Alexander Astrov CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 Word Count: 12,928 Abstract The Constructivist paradigm of International Relations (IR) theory has provided for an ‘aesthetic turn’ in IR. This turn can be applied to popular culture in order to theorize about the international system. Using the case study of the James Bond film series, this paper investigates the continuing relevancy of the espionage series through the Cold War and beyond in order to reveal new information about the nature of the international political system. Using the concept of the ‘empty signifier,’ this work establishes the shifting identity of James Bond in relation to four thematic icons in the films: the villains, locations, women and technology and their relation to the international political setting over the last 50 years of the films. Bond’s changing identity throughout the series reveals an increasingly globalized society that gives prominence to David Chandler’s theory about ‘empire in denial,’ in which Western states are ever more reluctant to take responsibility for their intervention abroad. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Professor Alexander Astrov for taking a chance with me on this project and guiding me through this difficult process. I would also like to acknowledge the constant support and encouragement from my IRES colleagues through the last year. -

The James Bond Quiz Eye Spy...Which Bond? 1

THE JAMES BOND QUIZ EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 1. 3. 2. 4. EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 5. 6. WHO’S WHO? 1. Who plays Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights? 2. Who makes his final appearance as M in Moonraker? 3. Which Bond character has diamonds embedded in his face? 4. In For Your Eyes Only, which recurring character does not appear for the first time in the series? 5. Who plays Solitaire in Live And Let Die? 6. Which character is painted gold in Goldfinger? 7. In Casino Royale, who is Solange married to? 8. In Skyfall, which character is told to “Think on your sins”? 9. Who plays Q in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? 10. Name the character who is the head of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Service in You Only Live Twice? EMOJI FILM TITLES 1. 6. 2. 7. ∞ 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. GUESS THE LOCATION 1. Who works here in Spectre? 3. Who lives on this island? 2. Which country is this lake in, as seen in Quantum Of Solace? 4. Patrice dies here in Skyfall. Name the city. GUESS THE LOCATION 5. Which iconic landmark is this? 7. Which country is this volcano situated in? 6. Where is James Bond’s family home? GUESS THE LOCATION 10. In which European country was this iconic 8. Bond and Anya first meet here, but which country is it? scene filmed? 9. In GoldenEye, Bond and Xenia Onatopp race their cars on the way to where? GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. In which Bond film did the iconic Aston Martin DB5 first appear? 2. -

Fleming? of Dr

BOOKING KING'S KILLER • • ...Or Maybe Ayn Fleming? Was the murderer of Dr. ers are politicians, bureaucrats, Martin Luther King Jr. a man self-styled intellectuals who are , influenced by two characters in evil and must be destroyed. Galt 1 contemporary fiction—one a glo- denounces mysticism and glori- I rified individualist who hates so- fies reason. His gospel is aboli- ciety and the other an Ian Flem- ti-m of the income tax, an end to ing arch villain? foreign aid and of social welfare legislation. At the end, as Galt The name of the man listed on and his cohorts fly to their At- the registration card of the car linked to the lantis they see New York writh- white Mustang ing in its last convulsions. slaying is "Eric Slarvo Galt." The FBI has been unable to find Ernst Stavro Blofeld is the an,thing to indicate that any. inuch-less philosophical villain sueh a person exists. of "Thunderball" and two other Fleming novels. Ili Ayn Rand's 1937 novel, "At- las Shrugged," the leader of a If the man who murderL tiny minority of people de- King was influenced by tie scribed as able, creative and ul- views of the fictional characters tra-conservative is "John Galt," or even just concocted an alia. And in some of Ian Fleming's from a combination of th James Bond stories, the leading names, an investigator migh enemy of the status quo is called An artist's unofficial concep- draw the conclusion that the fu "Ernst Stavro Blofeld." tion of Galt. -

MI6 Confirms Activision's 007 Status - Quantum of Solace(TM) Video Game Makes Retail Debut

MI6 Confirms Activision's 007 Status - Quantum of Solace(TM) Video Game Makes Retail Debut Quantum of Solace Theme Song to Rock Guitar Hero(R) World Tour in November SANTA MONICA, Calif., Oct 31, 2008 /PRNewswire-FirstCall via COMTEX News Network/ -- Can't wait for the new movie to step into the shoes of James Bond? Activision Publishing, Inc. (Nasdaq: ATVI) today announced that the Quantum of Solace(TM) video game, based on the eagerly anticipated "Quantum of Solace" and prior "Casino Royale" James Bond films, is dashing into European retail outlets today, and will be available in North American stores on November 4, 2008. Developed under license from EON Productions Ltd and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc. (MGM), the Quantum of Solace video game equips players with the weapons, espionage and hand-to-hand combat skills and overall charm needed to survive the covert lifestyle of legendary 007 secret agent James Bond. "Activision's Quantum of Solace video game marks the first time players can become the newly re-imagined, dangerous and cunningly efficient James Bond as portrayed by Daniel Craig," said Rob Kostich, Head of Marketing for Licensed Properties, Activision Publishing. "We're extremely pleased to release the game day and date with the new movie, so for those of us waiting for the new era in Bond gaming, Quantum of Solace has arrived." The Quantum of Solace video game balances a unique variety of gameplay elements, blending intense first-person action with a new third-person cover combat system, enabling players to strategically choose the best combat tactics for each situation. -

Things Are Not Enough Bond, Stiegler, and Technics

Things Are Not Enough Bond, Stiegler, and Technics CLAUS-ULRICH VIOL Discussions of Bond’s relationship with technology frequently centre around the objects he uses, the things he has at his disposal: what make is the car, what products have been placed in the flm, are the flm’s technical inventions realistic, visionary even !his can be observed in cinema foyers, fan circles, the media, as well as academia. #$en these discussions take an admiring turn, with commentators daz%led by the technological foresight of the flmic ideas; ' quite ofen too, especially in academic circles, views tend to be critical, connecting Bond’s technological overkill to some compensatory need in the character, seeing the technological objects as (props) that would and should not have to be ' *ee, for instance, publications like The Science of James Bond by Gresh and ,einberg -.//01, who set out to provide an “informative look at the real2world achievements and brilliant imaginations) behind the Bond gadgets, asking how realistic or “fant2 astic) the adventures and the equipment are and promising to thus probe into (the limits of science, the laws of nature and the future of technology” -back cover1" 3arker’s similar Death Rays, Jet Packs, Stunts and Supercars -.//41 includes discussions of the physics behind the action scenes -like stunts and chases1, but there remains a heavy preponderance of (ama%ing devices), (gadgets and gi%mos), “incredible cars), (reactors) and (guns) -v2vi1" ,eb pages and articles about (Bond Gadgets that 5ave Become 6eal), “Bond Gadgets 7ou 8an 9ctually Buy”, “Bond Gadgets that 8ould ,ork in 6eal :ife) and the like are legion. -

Rory Kinnear

RORY KINNEAR Film: Peterloo Henry Hunt Mike Leigh Peterloo Ltd Watership Down Cowslip Noam Murro 42 iBoy Ellman Adam Randall Wigwam Films Spectre Bill Tanner Sam Mendes EON Productions Trespass Against Us Loveage Adam Smith Potboiler Productions Man Up Sean Ben Palmer Big Talk Productions The Imitation Game Det Robert Nock Morten Tydlem Black Bear Pictures Cuban Fury Gary James Griffiths Big Talk Productions Limited Skyfall Bill Tanner Sam Mendes Eon Productions Broken* Bob Oswald Rufus Norris Cuba Pictures Wild Target Gerry Jonathan Lynne Magic Light Quantum Of Solace Bill Tanner Marc Forster Eon Productions Television: Guerrilla Ch Insp Nic Pence John Ridley & Sam Miller Showtime Quacks Robert Andy De Emmony Lucky Giant The Casual Vacancy Barry Fairbrother Jonny Campbell B B C Penny Dreadful (Three Series) Frankenstein's Creature Juan Antonio Bayona Neal Street Productions Lucan Lord Lucan Adrian Shergold I T V Studios Ltd Count Arthur Strong 1 + 2 Mike Graham Linehan Retort Southcliffe David Sean Durkin Southcliffe Ltd The Hollow Crown Richard Ii Various Neal Street Productions Loving Miss Hatto Young Barrington Coupe Aisling Walsh L M H Film Production Ltd Richard Ii Bolingbroke Rupert Goold Neal Street Productions Black Mirror; National Anthem Michael Callow Otto Bathurst Zeppotron Edwin Drood Reverend Crisparkle Diarmuid Lawrence B B C T V Drama Lennon Naked Brian Epstein Ed Coulthard Blast Films First Men Bedford Damon Thomas Can Do Productions Vexed Dan Matt Lipsey Touchpaper T V Cranford (two Series) Septimus Hanbury Simon Curtis B B C Beautiful People Ross David Kerr B B C The Thick Of It Ed Armando Iannucci B B C Waking The Dead James Fisher Dan Reed B B C Ashes To Ashes Jeremy Hulse Ben Bolt Kudos For The Bbc Minder Willoughby Carl Nielson Freemantle Steptoe & Sons Alan Simpson Michael Samuels B B C Plus One (pilot) Rob Black Simon Delaney Kudos Messiah V Stewart Dean Harry Bradbeer Great Meadow Rory Kinnear 1 Markham Froggatt & Irwin Limited Registered Office: Millar Court, 43 Station Road, Kenilworth, Warwickshire CV8 1JD Registered in England N0. -

The Man with the Golden Gun

MACMILLAN READERS UPPER LEVEL IAN FLEMING The Man with the Golden Gun Retold by Helen Holwill MACMILLAN 1 ‘Can I Help You?’ veryone thought that Commander James Bond, one of the E best agents in the British Secret Intelligence Service, was dead. A year ago the Head of the Secret Service, who was a man known only by the initial ‘M’, had chosen Bond to go to Japan on a highly important mission. His task had been to gather secret information from the Japanese about the Soviet Union. But the job had gone badly wrong and Bond had become involved in a dangerous battle with a known criminal called Blofeld. It was thought that Bond had killed Blofeld, but no one knew what had happened to Bond himself after the fight. He had simply disappeared. Those who knew him at the Secret Service had now given up any hope that he could still be alive. However, Bond was not dead; he had been captured by the Russians. They had taken him to a secret medical institute in Leningrad, where the KGB began trying to brainwash8 him. After many months of torture9, Bond had grown weaker and weaker and could take no more. The KGB had finally won their battle to control his mind. A man called ‘Colonel Boris’ had then spent several more months carefully preparing Bond for his return to England. He had told Bond exactly how to behave, what to wear and even which hotel to stay in. He had also told him who to contact at the Secret Service Headquarters and precisely how to answer their many questions. -

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

Theaters 3 & 4 the Grand Lodge on Peak 7

The Grand Lodge on Peak 7 Theaters 3 & 4 NOTE: 3D option is only available in theater 3 Note: Theater reservations are for 2 hours 45 minutes. Movie durations highlighted in Orange are 2 hours 20 minutes or more. Note: Movies with durations highlighted in red are only viewable during the 9PM start time, due to their excess length Title: Genre: Rating: Lead Actor: Director: Year: Type: Duration: (Mins.) The Avengers: Age of Ultron 3D Action PG-13 Robert Downey Jr. Joss Whedon 2015 3D 141 Born to be Wild 3D Family G Morgan Freeman David Lickley 2011 3D 40 Captain America : The Winter Soldier 3D Action PG-13 Chris Evans Anthony Russo/ Jay Russo 2014 3D 136 The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader 3D Adventure PG Georgie Henley Michael Apted 2010 3D 113 Cirque Du Soleil: Worlds Away 3D Fantasy PG Erica Linz Andrew Adamson 2012 3D 91 Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs 2 3D Animation PG Ana Faris Cody Cameron 2013 3D 95 Despicable Me 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2010 3D 95 Despicable Me 2 3D Animation PG Steve Carell Pierre Coffin 2013 3D 98 Finding Nemo 3D Animation G Ellen DeGeneres Andrew Stanton 2003 3D 100 Gravity 3D Drama PG-13 Sandra Bullock Alfonso Cuaron 2013 3D 91 Hercules 3D Action PG-13 Dwayne Johnson Brett Ratner 2014 3D 97 Hotel Transylvania Animation PG Adam Sandler Genndy Tartakovsky 2012 3D 91 Ice Age: Continetal Drift 3D Animation PG Ray Romano Steve Martino 2012 3D 88 I, Frankenstein 3D Action PG-13 Aaron Eckhart Stuart Beattie 2014 3D 92 Imax Under the Sea 3D Documentary G Jim Carrey Howard Hall -

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows [Parts I &

Document generated on 09/25/2021 1:21 a.m. Séquences La revue de cinéma Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows [Parts I & II] Demi-tour de magie Harry Potter et les reliques de la mort (parties I et II) — Grande-Bretagne / États-Unis 2010 et 2011, 145 et 130 minutes Pamela Pianezza Number 274, September–October 2011 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/64903ac See table of contents Publisher(s) La revue Séquences Inc. ISSN 0037-2412 (print) 1923-5100 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Pianezza, P. (2011). Review of [Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows [Parts I & II] : demi-tour de magie / Harry Potter et les reliques de la mort (parties I et II) — Grande-Bretagne / États-Unis 2010 et 2011, 145 et 130 minutes]. Séquences, (274), 44–45. Tous droits réservés © La revue Séquences Inc., 2011 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ 44 Les films | Gros plan Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows [Part I] Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows [Parts I & II] Demi-tour de magie Lancée en 2001, la saga Harry Potter s’est imposée comme la franchise la plus ambitieuse (et rentable) de l’histoire du cinéma. -

Cineplex Store

Creative & Production Services, 100 Yonge St., 5th Floor, Toronto ON, M5C 2W1 File: AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920 Publication: Cineplex Mag Trim: 8” x 10.5” Deadline: September 2020 Bleed: 0.125” Safety: 7.5” x 10” Colours: CMYK In Market: September 2020 Notes: Designer: KB A simple conversation plus a tailored plan. Introducing Advice+ is an easier way to create a plan together that keeps you heading in the right direction. Talk to an Advisor about Advice+ today, only from Scotiabank. ® Registered trademark of The Bank of Nova Scotia. AD Advice+ E 8x10.5 0920.indd 1 2020-09-17 12:48 PM HOLIDAY 2020 CONTENTS VOLUME 21 #5 ↑ 2021 Movie Preview’s Ghostbusters: Afterlife COVER STORY 16 20 26 31 PLUS HOLIDAY SPECIAL GUY ALL THE 2021 MOVIE GIFT GUIDE We catch up with KING’S MEN PREVIEW Stressed about Canada’s most Writer-director Bring on 2021! It’s going 04 EDITOR’S Holiday gift-giving? lovable action star Matthew Vaughn and to be an epic year of NOTE Relax, whether you’re Ryan Reynolds to find star Ralph Fiennes moviegoing jam-packed shopping online or out how he’s spending tell us about making with 2020 holdovers 06 CLICK! in stores we’ve got his downtime. Hint: their action-packed and exciting new titles. you covered with an It includes spreading spy pic The King’s Man, Here we put the spotlight 12 SPOTLIGHT awesome collection of goodwill and talking a more dramatic on must-see pics like CANADA last-minute presents about next year’s prequel to the super- Top Gun: Maverick, sure to please action-comedy Free Guy fun Kingsman films F9, Black Widow -

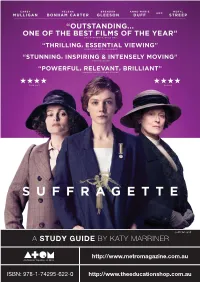

Suffragette Study Guide

© ATOM 2015 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN: 978-1-74295-622-0 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Running time: 106 minutes » SUFFRAGETTE Suffragette (2015) is a feature film directed by Sarah Gavron. The film provides a fictional account of a group of East London women who realised that polite, law-abiding protests were not going to get them very far in the battle for voting rights in early 20th century Britain. click on arrow hyperlink CONTENTS click on arrow hyperlink click on arrow hyperlink 3 CURRICULUM LINKS 19 8. Never surrender click on arrow hyperlink 3 STORY 20 9. Dreams 6 THE SUFFRAGETTE MOVEMENT 21 EXTENDED RESPONSE TOPICS 8 CHARACTERS 21 The Australian Suffragette Movement 10 ANALYSING KEY SEQUENCES 23 Gender justice 10 1. Votes for women 23 Inspiring women 11 2. Under surveillance 23 Social change SCREEN EDUCATION © ATOM 2015 © ATOM SCREEN EDUCATION 12 3. Giving testimony 23 Suffragette online 14 4. They lied to us 24 ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS 15 5. Mrs Pankhurst 25 APPENDIX 1 17 6. ‘I am a suffragette after all.’ 26 APPENDIX 2 18 7. Nothing left to lose 2 » CURRICULUM LINKS Suffragette is suitable viewing for students in Years 9 – 12. The film can be used as a resource in English, Civics and Citizenship, History, Media, Politics and Sociology. Links can also be made to the Australian Curriculum general capabilities: Literacy, Critical and Creative Thinking, Personal and Social Capability and Ethical Understanding. Teachers should consult the Australian Curriculum online at http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/ and curriculum outlines relevant to these studies in their state or territory.