Things Are Not Enough Bond, Stiegler, and Technics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Bond in Our Sights: a Close Look at 'A View to a Kill

James Bond in Our Sights: A Close Look at 'a View to a Kill' - Andrew Mcness - 2011 - 124 pages - Author Solutions, 2011 - 9781465382399 DailyMail.com tracked down the 81-year-old's home to a quiet community just outside the coastal city of Arecibo on Puerto Rico's north coast. Blue tarps are seen atop her grandmother's home, which appears to still sustain damage since the passing of Hurricane Maria and Hurricane Irma. A woman who identified herself as AOC's aunt told us, 'We are private people, we don't talk about our family. We don't speak for the community'. Her aunt said: 'In this area people need a lot of help. Largely seen by fans and critics alike as the overly-formulaic orphan child of the 1970’s smash Bond hits, A View To A Kill (1985), the 14th instalment of the modern cinematic classic, is the film in question in Andrew McNess’s "James Bond In Our Sights". McNess puts up an exuberant display of a film critic’s sharp, trenchant observations and a complete fan’s reverence for the condign qualities of Ian Fleming’s cool and womanising spy-hero. The film marked Roger Moore’s final performance as Agent 007. However, in the author’s superbly well-reasoned contention, A View to a Kill's intriguing, ev But a closer look at character motivation, development, relationships, and some plot structure shows that the film actually goes out of it's way to try something new, on a rather epic canvas. I found this aspect of the book fascinating and it made me re-watch the movie with a new sense of appreciation. I am already a huge supporter of the underrated A View to a Kill and was quite delighted to find this book. -

James Bond a 50 The

JAMES BOND: SIGNIFYING CHANGING IDENTITY THROUGH THE COLD WAR AND BEYOND By Christina A. Clopton Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Masters of Arts Supervisor: Professor Alexander Astrov CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2014 Word Count: 12,928 Abstract The Constructivist paradigm of International Relations (IR) theory has provided for an ‘aesthetic turn’ in IR. This turn can be applied to popular culture in order to theorize about the international system. Using the case study of the James Bond film series, this paper investigates the continuing relevancy of the espionage series through the Cold War and beyond in order to reveal new information about the nature of the international political system. Using the concept of the ‘empty signifier,’ this work establishes the shifting identity of James Bond in relation to four thematic icons in the films: the villains, locations, women and technology and their relation to the international political setting over the last 50 years of the films. Bond’s changing identity throughout the series reveals an increasingly globalized society that gives prominence to David Chandler’s theory about ‘empire in denial,’ in which Western states are ever more reluctant to take responsibility for their intervention abroad. CEU eTD Collection i Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to Professor Alexander Astrov for taking a chance with me on this project and guiding me through this difficult process. I would also like to acknowledge the constant support and encouragement from my IRES colleagues through the last year. -

The James Bond Quiz Eye Spy...Which Bond? 1

THE JAMES BOND QUIZ EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 1. 3. 2. 4. EYE SPY...WHICH BOND? 5. 6. WHO’S WHO? 1. Who plays Kara Milovy in The Living Daylights? 2. Who makes his final appearance as M in Moonraker? 3. Which Bond character has diamonds embedded in his face? 4. In For Your Eyes Only, which recurring character does not appear for the first time in the series? 5. Who plays Solitaire in Live And Let Die? 6. Which character is painted gold in Goldfinger? 7. In Casino Royale, who is Solange married to? 8. In Skyfall, which character is told to “Think on your sins”? 9. Who plays Q in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service? 10. Name the character who is the head of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Service in You Only Live Twice? EMOJI FILM TITLES 1. 6. 2. 7. ∞ 3. 8. 4. 9. 5. 10. GUESS THE LOCATION 1. Who works here in Spectre? 3. Who lives on this island? 2. Which country is this lake in, as seen in Quantum Of Solace? 4. Patrice dies here in Skyfall. Name the city. GUESS THE LOCATION 5. Which iconic landmark is this? 7. Which country is this volcano situated in? 6. Where is James Bond’s family home? GUESS THE LOCATION 10. In which European country was this iconic 8. Bond and Anya first meet here, but which country is it? scene filmed? 9. In GoldenEye, Bond and Xenia Onatopp race their cars on the way to where? GENERAL KNOWLEDGE 1. In which Bond film did the iconic Aston Martin DB5 first appear? 2. -

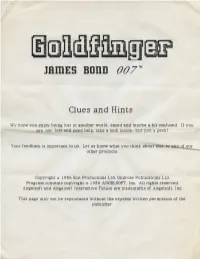

Goldfinger-Hints

JRIDES BORD Clues and Hints We hope you enjoy being lost in another world, dazed and maybe a bit confused. If you are too lo-stand need help, take a look inside- but just a peek! Your feedback is important to us. Let us know what you think about this. other products. Copyright © 1986 Eon Productions Ltd, Glidrose Publications Ltd. Program contents copyright © 1 986 ANGELSOFT , Inc. All rights reserved. Angelsoft and Angelsoft Interactive Fiction are trademarks of Angelsoft, Inc. This page may not. be reproduced without the express written permission of the publisher. • Thank you for buying Mindscape's Goldfinger. We trust you are enjoying it immensely. Now let's see if we can get you onto the right path towards defeating the evil villain Goldfinger before his dastardly plot sends the world economic community into total chaos. Use the hints sparingly 007. GOOD LUCK! -IN THE CAR CHASE- Q: I keep getting caught in the car chase! A: 007, you are noted for driving very sophisticated automobiles with lots of toys that might come in handy at times like this. Q: What kind of toys? A: Check the armrest, maybe it's more than it appears to be! Q: The lead Mercedes keeps catching me! A: There's an old saying, "things come in threes". Q: I still can't get away from the Mercedes! A: Remember your auto has some very special features. -AT THE LOOKOUT- Q: I've lost the Mercedes, what do I do now? A: Maybe you should take a closer look at the beautiful scene. -

'His Name's Bond ... James Bond'

1 Read and listen to the article. ‘His name’s Bond ... James Bond’ Who created the character of James Bond? The British writer Ian Fleming created James Bond in his 1953 novel Casino Royale. He wrote a series of books about the secret agent between 1953 and 1966. The books have sold more than 18 million copies around the world in many different languages. Who does James Bond work for? Bond works for MI6, the British Secret Services. His colleagues at MI6 don’t have names – they have letters. M is Bond’s boss and Q develops high-tech devices. What is James Bond’s code number? His code number is 007. In the first novel, Casino Royale, Bond kills two spies. The prefix 00 represents these two assassinations. Since then Bond has killed more than 150 villains! © Oxford University Press PHOTOCOPIABLE How does he defeat his enemies? His enemies are super-villains who want to control the world. Bond uses his intelligence, athleticism and high-tech weapons and devices. In the early stories these were guns or explosives that looked like everyday objects (a watch or a pen, for example). In later stories, the devices became more sophisticated and included x-ray glasses and a jetpack that he wore on his back to fly. In Die Another Day his favourite Aston Martin car became invisible! How many James Bond films have there been? There have been 22 official James Bond films. The first film was Dr No in 1962. It starred Sean Connery as Bond. The Bond films are the second most successful series of films in the history of cinema. -

“Licence to Save Energy” at Over 3,000 Metres Ts Gh Hli the Ice Q Design Restaurant Sits on the Peak of Gaislachkogl, in the Austrian Ski Resort of Sölden

“Licence to save energy” at over 3,000 metres ts gh hli The ice Q design restaurant sits on the peak of Gaislachkogl, in the Austrian ski resort of Sölden. It is famous for being the hig starting point of spectacular chase scenes in the James Bond film “Spectre”. The building, constructed on permafrost and of- ER UT fering a 360-degree panoramic view, features an automation solution from SAUTER to achieve outstanding energy efficiency. SA © Rudi Wyhlidal © Rudi Wyhlidal Skiers have left their tracks in the snow-covered mountain slopes of and a panoramic sun terrace. Thanks to the huge glass façade, Sölden in Austria for more than 100 years. During this time, the guests can also enjoy the breathtaking 360-degree panorama of the former mountain village has grown into a beloved winter sports des- Ötztal alpine landscape from the comfort of the building’s interior. tination in the Alps with exclusive accommodation and state-of-the-art lift systems. Challenged with unusual and extreme temperature conditions, this development required sound technical expertise throughout the In the 1960s, engineers started developing the area on the construction. At this altitude, the subsurface is frozen all year round. 3.056-metre-high Gaislachkogl peak. Some 50 years later, to meet Flexible foundations prevent subsidence and stop the building from increasing tourism demands and impress with something unique, shifting in the icy ground. The unusually short deadline also meant Sölden upgraded the cable car and replaced the outdated summit that SAUTER had to pull out all the stops. The team therefore some- restaurant. -

The 007Th Minute Ebook Edition

“What a load of crap. Next time, mate, keep your drug tripping private.” JACQUES A person on Facebook. STEWART “What utter drivel” Another person on Facebook. “I may be in the minority here, but I find these editorial pieces to be completely unreadable garbage.” Guess where that one came from. “No, you’re not. Honestly, I think of this the same Bond thinks of his obituary by M.” Chap above’s made a chum. This might be what Facebook is for. That’s rather lovely. Isn’t the internet super? “I don’t get it either and I don’t have the guts to say it because I fear their rhetoric or they’d might just ignore me. After reading one of these I feel like I’ve walked in on a Specter round table meeting of which I do not belong. I suppose I’m less a Bond fan because I haven’t read all the novels. I just figured these were for the fans who’ve read all the novels including the continuation ones, fan’s of literary Bond instead of the films. They leave me wondering if I can even read or if I even have a grasp of the language itself.” No comment. This ebook is not for sale but only available as a free download at Commanderbond.net. If you downloaded this ebook and want to give something in return, please make a donation to UNICEF, or any other cause of your personal choice. BOOK Trespassers will be masticated. Fnarr. BOOK a commanderbond.net ebook COMMANDERBOND.NET BROUGHT TO YOU BY COMMANDERBOND.NET a commanderbond.net book Jacques I. -

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

A Queer Analysis of the James Bond Canon

MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL May 2019 Copyright 2019 by Grant C. Hester ii MALE BONDING: A QUEER ANALYSIS OF THE JAMES BOND CANON by Grant C. Hester This dissertation was prepared under the direction of the candidate's dissertation advisor, Dr. Jane Caputi, Center for Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, Communication, and Multimedia and has been approved by the members of his supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of the Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Khaled Sobhan, Ph.D. Interim Dean, Graduate College iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Jane Caputi for guiding me through this process. She was truly there from this paper’s incubation as it was in her Sex, Violence, and Hollywood class where the idea that James Bond could be repressing his homosexuality first revealed itself to me. She encouraged the exploration and was an unbelievable sounding board every step to fruition. Stephen Charbonneau has also been an invaluable resource. Frankly, he changed the way I look at film. His door has always been open and he has given honest feedback and good advice. Oliver Buckton possesses a knowledge of James Bond that is unparalleled. I marvel at how he retains such information. -

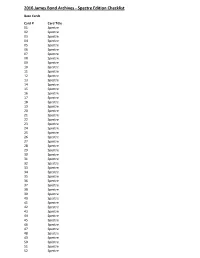

2016 James Bond Archives - Spectre Edition Checklist

2016 James Bond Archives - Spectre Edition Checklist Base Cards Card # Card Title 01 Spectre 02 Spectre 03 Spectre 04 Spectre 05 Spectre 06 Spectre 07 Spectre 08 Spectre 09 Spectre 10 Spectre 11 Spectre 12 Spectre 13 Spectre 14 Spectre 15 Spectre 16 Spectre 17 Spectre 18 Spectre 19 Spectre 20 Spectre 21 Spectre 22 Spectre 23 Spectre 24 Spectre 25 Spectre 26 Spectre 27 Spectre 28 Spectre 29 Spectre 30 Spectre 31 Spectre 32 Spectre 33 Spectre 34 Spectre 35 Spectre 36 Spectre 37 Spectre 38 Spectre 39 Spectre 40 Spectre 41 Spectre 42 Spectre 43 Spectre 44 Spectre 45 Spectre 46 Spectre 47 Spectre 48 Spectre 49 Spectre 50 Spectre 51 Spectre 52 Spectre 53 Spectre 54 Spectre 55 Spectre 56 Spectre 57 Spectre 58 Spectre 59 Spectre 60 Spectre 61 Spectre 62 Spectre 63 Spectre 64 Spectre 65 Spectre 66 Spectre 67 Spectre 68 Spectre 69 Spectre 70 Spectre 71 Spectre 72 Spectre 73 Spectre 74 Spectre 75 Spectre 76 Spectre Diamond Are Forever Throwback Cards (1:6 packs) Card # Card Title 01 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 02 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 03 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 04 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 05 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 06 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 07 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 08 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 09 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 10 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 11 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 12 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 13 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 14 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 15 Diamond Are Forever Throwback Set 16 Diamond Are Forever -

International Spy Museum

International Spy Museum Searchable Master Script, includes all sections and areas Area Location, ID, Description Labels, captions, and other explanatory text Area 1 – Museum Lobby M1.0.0.0 ΚΑΤΆΣΚΟΠΟΣ SPY SPION SPIJUN İSPİYON SZPIEG SPIA SPION ESPION ESPÍA ШПИОН Language of Espionage, printed on SCHPION MAJASUSI windows around entrance doors P1.1.0.0 Visitor Mission Statement For Your Eyes Only For Your Eyes Only Entry beyond this point is on a need-to-know basis. Who needs to know? All who would understand the world. All who would glimpse the unseen hands that touch our lives. You will learn the secrets of tradecraft – the tools and techniques that influence battles and sway governments. You will uncover extraordinary stories hidden behind the headlines. You will meet men and women living by their wits, lurking in the shadows of world affairs. More important, however, are the people you will not meet. The most successful spies are the unknown spies who remain undetected. Our task is to judge their craft, not their politics – their skill, not their loyalty. Our mission is to understand these daring professionals and their fallen comrades, to recognize their ingenuity and imagination. Our goal is to see past their maze of mirrors and deception to understand their world of intrigue. Intelligence facts written on glass How old is spying? First record of spying: 1800 BC, clay tablet from Hammurabi regarding his spies. panel on left side of lobby First manual on spy tactics written: Over 2,000 years ago, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. 6 video screens behind glass panel with facts and images. -

Bakalářská Práce

TECHNICKÁ UNIVERZITA V LIBERCI FAKULTA TEXTILNÍ BAKALÁŘSKÁ PRÁCE LIBEREC 2011 LUCIE MICHALCOVÁ TECHNICKÁ UNIVERZITA V LIBERCI FAKULTA TEXTILNÍ BOND GIRLS BOND GIRLS LIBEREC 2011 LUCIE MICHALCOVÁ Poděkování Děkuji vedoucí bakalářské práce Mgr. Art Zuzaně Veselé za odborné rady a konzultace. Dále bych chtěla poděkovat Bc. Jakubovi Viktorovi za nafocení celé kolekce a modelkám Dominice a Katce. Děkuji také prodejně MIXER za zapůjčení obuvi. www.mixershoes.com Anotace Bakalářská práce se zabývá tématikou filmů o Jamesi Bondovi, konkrétně o Bond girls. V teoretické části je vypsaná chronologie všech filmů a hlavních hereckých představitelů Jamese Bonda. Dále je popsán stručný děj vybraných filmů a úlohy hlavních hrdinek. Je zde sledováno hlavně jejich odívání a kostýmy. U kaţdého filmu je zmíněn kostýmní výtvarník nebo designér, který modely vytvářel. Praktická část zahrnuje kolekci osmi modelů, určených pro budoucí Bond girls. Klíčová slova: filmy, James Bond, Bond girls, móda, kostýmy Annotation This project concerns about the theme of James Bond’s films, concretely about Bond girls. Theory part deals with chronology of all films and principal actors of James Bond. There is a jot description of selected films and roles of main female creatress. Their fashion and costumes is observed there. In every film there is a forenamed costumes artist or designer who created models. Practical part includes collection of eight models designate for future bond girls. Keywords: films, James Bond, Bond girls, fashion, costumes OBSAH 1 ÚVOD.......................................................................................................................