A Critical Analysis of the Nature of Things (To Include the Play Itself)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kathleen Lonsdale

Edited by KATHLEEN LONSDALE PRICE 3/6 Quakers Visit Russia Ediled by KATHLEEN LONSDALE Published by the Eash West Reialions Group of the Frle/idt' Peace Cotn/tti.dee, Friends House, Euston Road, London, N. IK t. First Edition July 1952 Reprinted October 1952 QUAKERS VISIT RUSSIA Edited by KATHLEEN LONSDALE Declaration to Charles II, 1660 "JKe utterly deny all outward wars and strife, and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretence whatever; this is our testimony to the whole world. The Spirit of Christ by which we are guided is not changeable, so as once to command us from a thing as evil and again to move unto it; and we certainly know and testify to the world, that the Spirit of Christ, which leads us into all Truth, will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the Kingdom of Christ nor for the Kingdoms of this world.” Message of Goodwill to AM Men, 1956 (frwd In Engltih, French, German and Jtustton') "In face of deepening fear and mutual distrust throughout the world, the Society of Friends (Quakers) is moved to declare goodwill to all men everywhere. Friends appeal for the avoidance of words and deeds that increase suspicion and ill- feeling, for renewed efforts at understanding and for positive attempts to build a true peace. They are convinced that reconciliation is possible. They hope that this simple word, translated into many tongues, may itself help to create the new spirit in which the resources of the world will be diverted from war dike purposes and applied to the welfare of mankind.” Hl CONTENTS Chapter 1. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE STORY BEHIND THE STORIES British and Dominion War Correspondents in the Western Theatres of the Second World War Brian P. D. Hannon Ph.D. Dissertation The University of Edinburgh School of History, Classics and Archaeology March 2015 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Acknowledgements ……………………………………………………………… 5 Introduction ……………………………………………………………………… 6 The Media Environment ……………...……………….……………………….. 28 What Made a Correspondent? ……………...……………………………..……. 42 Supporting the Correspondent …………………………………….………........ 83 The Correspondent and Censorship …………………………………….…….. 121 Correspondent Techniques and Tools ………………………..………….......... 172 Correspondent Travel, Peril and Plunder ………………………………..……. 202 The Correspondents’ Stories ……………………………….………………..... 241 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………. 273 Bibliography ………………………………………………………………...... 281 Appendix …………………………………………...………………………… 300 3 ABSTRACT British and Dominion armed forces operations during the Second World War were followed closely by a journalistic army of correspondents employed by various media outlets including news agencies, newspapers and, for the first time on a large scale in a war, radio broadcasters. -

Isms Through a Prism

MONDAY, JANUARY 20, 2020 In honor of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day, we are exploring various forms of biases that create schisms. We encourage your introspection. isms through a prism ableism ageism Let’s not be oblivious Judge not youth or age BY CHERYL CHARLES BY ELYSE CARMOSINO I got out of bed this morning, al- Since a New York Times article de- though perhaps a bit more gingerly clared the rise in popularity of mil- than I did in my younger days. lennial and Gen Z internet meme Yes, these exercise routines leave me “OK boomer” to be “the end of friend- a little more sore, for a whole lot longer. ly generational relations,” the topic But I’ve always been able to walk, and of age-related discrimination on both move, and get pretty much anywhere ends of the scale has resurfaced as a ableism, A7 ageism, A7 Ableism Ageism Colorism Heterosexism Racism Se xism PAGE DESIGN | MARK SUTHERLAND colorism heterosexism racism sexism A paler Who’s to say Let’s look Still a long shade of bias what’s normal? beyond color way to go BY THOR JOURGENSEN BY GAYLA CAWLEY BY STEVE KRAUSE BY CAROLINA TRUJILLO I had a friend who was For the past couple of To start with, racism is Sex·ism (noun) prejudice, Puerto Rican and proud of years, I’ve been writing a an insidious social condi- stereotyping, or discrimi- her family’s roots in Spain. bi-weekly column and have tion. Every time we think nation, typically against Her skin was as light as intentionally steered clear we’ve conquered it, or at women, on the basis of sex. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Bourgeois Like Me

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Bourgeois Like Me: Architecture, Literature, and the Making of the Middle Class in Post- War London A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in English by Elizabeth Marly Floyd Committee in charge: Professor Maurizia Boscagli, Chair Professor Enda Duffy Professor Glyn Salton-Cox June 2019 The dissertation of Elizabeth Floyd is approved. _____________________________________________ Enda Duffy _____________________________________________ Glyn Salton-Cox _____________________________________________ Maurizia Boscagli, Committee Chair June 2019 Bourgeois Like Me: Architecture, Literature, and the Making of the Middle Class in Post- War Britain Copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Floyd iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project would not have been possible without the incredible and unwavering support I have received from my colleagues, friends, and family during my time at UC Santa Barbara. First and foremost, I would like to thank my committee for their guidance and seeing this project through its many stages. My ever-engaging chair, Maurizia Boscagli, has been a constant source of intellectual inspiration. She has encouraged me to be a true interdisciplinary scholar and her rigor and high intellectual standards have served as an incredible example. I cannot thank her enough for seeing potential in my work, challenging my perspective, and making me a better scholar. Without her support and guidance, I could not have embarked on this project, let alone finish it. She has been an incredible mentor in teaching and advising, and I hope to one day follow her example and inspire as many students as she does with her engaging, thoughtful, and rigorous seminars. -

TRAPPING a STAR in a MAGNETIC DOUGHNUT the Physics of Magnetic Confinement Fusion

Spring 2016, Number 8 Department of Physics Newsletter TRAPPING A STAR IN A MAGNETIC DOUGHNUT The physics of magnetic confinement fusion RATTLING DARK MATTER THE CAGE: IN OUR GALAXY Making new superconductors Novel dynamics is bringing the Galaxy's and gravitational waves: using lasers dark matter into much sharper focus a personal reaction ALUMNI STORIES EVENTS PEOPLE Richard JL Senior and Elspeth Garman Remembering Dick Dalitz; Oxford Five minutes with Geoff Stanley; reflect on their experiences celebrates Nobel Prize; Physics Challenge Awards and Prizes Day and many more events www.physics.ox.ac.uk SCIENCE NEWS SCIENCE NEWS www.physics.ox.ac.uk/research www.physics.ox.ac.uk/research Prof James Binney FRS Right: Figure 2. The red arrows show the direction of the Galaxy’s gravitational field by our current DARK MATTER reckoning. The blue lines show the direction the field would have if the disc were massless. The mass © JOHN CAIRNS JOHN © IN OUR GALAXY of the disc tips the field direction In the Rudolf Peierls Centre for Theoretical Physics novel dynamics is towards the equatorial plane. A more massive disc would tip it bringing the Galaxy's dark matter into much sharper focus further. Far right: Figure 3. The orbits in In 1937 Fritz Zwicky pointed out that in clusters of clouds of hydrogen to large distances from the centre of the R plane of two stars that both galaxies like that shown in Fig. 1, galaxies move much NGC 3198. The data showed that gas clouds moved on z move past the Sun with a speed of faster than was consistent with estimates of the masses perfectly circular orbits at a speed that was essentially 72 km s−1. -

Postmodernist Occasions: Language, Fictionality and History in South Asian Novels

i Postmodernist Occasions: Language, Fictionality and History in South Asian Novels By Ayesha Ashraf MA English Literature, Sardar Bahadur Khan Women University Quetta, 2006 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In English To FACULTY OF ENGLISH STUDIES NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES, ISLAMABAD ©Ayesha Ashraf 2017 ii NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF MODERN LANGUAGES FACULTY OF ENGLISH STUDIES THESIS AND DEFENSE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have read the following thesis, examined the defense, are satisfied with the overall exam performance, and recommend the thesis to the Faculty of English Studies for acceptance: Thesis Title: Postmodernist Occasions: Language, Fictionality and History in South Asian Novels Submitted By: Ayesha Ashraf Registration #: 589-M.Phil/Lit/2011(Jan) Doctor of Philosophy Degree name in full English Literature Name of Discipline Prof. Dr. Munawar Iqbal Gondal _______________________ Name of Research Supervisor Signature of Research Supervisor Prof. Dr. Muhammad Safeer Awan _______________________ Name of Dean (FOES) Signature of Dean (FOES) Maj. Gen. Muhammad Jaffar (R) _______________________ Name of Rector (for PhD Thesis) Signature of Rector Date iii Candidate Declaration Form I Ayesha Ashraf Daughter of Muhammad Ashraf Registration # 589-M.Phil/Lit/2011(Jan) Discipline English Literature Candidate of Doctor of Philosophy at the National University of Modern Languages do hereby declare that the thesis Postmodernist Occasions: Language, Fictionality and History in South Asian Novels submitted by me in partial fulfillment of PhD degree, is my original work, and has not been submitted or published earlier. I also solemnly declare that it shall not, in future, be submitted by me for obtaining any other degree from this or any other university or institution. -

2010–2011 Our Mission

ANNUAL REPORT 2010–2011 OUR MISSION The Indianapolis Museum of Art serves the creative interests of its communities by fostering exploration of art, design, and the natural environment. The IMA promotes these interests through the collection, presentation, interpretation, and conservation of its artistic, historic, and environmental assets. FROM THE CHAIRMAN 02 FROM THE MELVIN & BREN SIMON DIRECTOR AND CEO 04 THE YEAR IN REVIEW 08 EXHIBITIONS 18 AUDIENCE ENGAGEMENT 22 PUBLIC PROGRAMS 24 ART ACQUISITIONS 30 LOANS FROM THE COLLECTION 44 DONORS 46 IMA BOARD OF GOVERNORS 56 AFFILIATE GROUP LEADERSHIP 58 IMA STAFF 59 FINANCIAL REPORT 66 Note: This report is for fiscal year July 2010 through June 2011. COVER Thornton Dial, American, b. 1928, Don’t Matter How Raggly the Flag, It Still Got to Tie Us Together (detail), 2003, mattress coils, chicken wire, clothing, can lids, found metal, plastic twine, wire, Splash Zone compound, enamel, spray paint, on canvas on wood, 71 x 114 x 8 in. James E. Roberts Fund, Deaccession Sculpture Fund, Xenia and Irwin Miller Fund, Alice and Kirk McKinney Fund, Anonymous IV Art Fund, Henry F. and Katherine DeBoest Memorial Fund, Martha Delzell Memorial Fund, Mary V. Black Art Endowment Fund, Elizabeth S. Lawton Fine Art Fund, Emma Harter Sweetser Fund, General Endowed Art Fund, Delavan Smith Fund, General Memorial Art Fund, Deaccessioned Contemporary Art Fund, General Art Fund, Frank Curtis Springer & Irving Moxley Springer Purchase Fund, and the Mrs. Pierre F. Goodrich Endowed Art Fund 2008.182 BACK COVER Miller House and Garden LEFT The Wood Pavilion at the IMA 4 | FROM THE CHAIRMAN FROM THE CHAIRMAN | 5 RESEARCH LEADERSHIP From the In addition to opening the new state-of-the-art Conservation Science Laboratory this past March, the IMA has fulfilled the challenge grant from the Andrew W. -

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY Theo James presenting a bouquet to HM The Queen on the occasion of her bicentenary visit, 7 December 1999. by Frank A.J.L. James The Director, Susan Greenfield, looks on Front page: Façade of the Royal Institution added in 1837. Watercolour by T.H. Shepherd or more than two hundred years the Royal Institution of Great The Royal Institution was founded at a meeting on 7 March 1799 at FBritain has been at the centre of scientific research and the the Soho Square house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph popularisation of science in this country. Within its walls some of the Banks (1743-1820). A list of fifty-eight names was read of gentlemen major scientific discoveries of the last two centuries have been made. who had agreed to contribute fifty guineas each to be a Proprietor of Chemists and physicists - such as Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday, a new John Tyndall, James Dewar, Lord Rayleigh, William Henry Bragg, INSTITUTION FOR DIFFUSING THE KNOWLEDGE, AND FACILITATING Henry Dale, Eric Rideal, William Lawrence Bragg and George Porter THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION, OF USEFUL MECHANICAL - carried out much of their major research here. The technological INVENTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS; AND FOR TEACHING, BY COURSES applications of some of this research has transformed the way we OF PHILOSOPHICAL LECTURES AND EXPERIMENTS, THE APPLICATION live. Furthermore, most of these scientists were first rate OF SCIENCE TO THE COMMON PURPOSES OF LIFE. communicators who were able to inspire their audiences with an appreciation of science. -

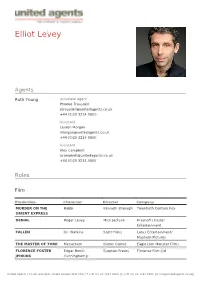

Elliot Levey

Elliot Levey Agents Ruth Young Associate Agent Phoebe Trousdell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Lauren Morgan [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Alex Campbell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company MURDER ON THE Rabbi Kenneth Branagh Twentieth Century Fox ORIENT EXPRESS DENIAL Roger Levey Mick Jackson Krasnoff / Foster Entertainment FALLEN Dr. Watkins Scott Hicks Lotus Entertainment/ Mayhem Pictures THE MASTER OF YORK Menachem Kieron Quirke Eagle Lion Monster Films FLORENCE FOSTER Edgar Booth Stephen Frears Florence Film Ltd JENKINS Cunningham Jr United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE LADY IN THE VAN Director Nicholas Hytner Van Production Ltd. SPOOKS Philip Emmerson Bharat Nalluri Shine Pictures & Kudos PHILOMENA Alex Stephen Frears Lost Child Limited THE WALL Stephen Cam Christiansen National film Board of Canada THE QUEEN Stephen Frears Granada FILTH AND WISDOM Madonna HSI London SONG OF SONGS Isaac Josh Appignanesi AN HOUR IN PARADISE Benjamin Jan Schutte BOOK OF JOHN Nathanael Philip Saville DOMINOES Ben Mirko Seculic JUDAS AND JESUS Eliakim Charles Carner Paramount QUEUES AND PEE Ben Despina Catselli Pinhead Films JASON AND THE Canthus Nick Willing Hallmark ARGONAUTS JESUS Tax Collector Roger Young Andromeda Prods DENIAL Roger Levey Denial LTD Television Production Character Director Company -

Crystallography News British Crystallographic Association

Crystallography News British Crystallographic Association Issue No. 99 December 2006 ISSN 1467-2790 BCA Spring Meeting 2007 - Canterbury p8-15 ECM Meeting p16-19 ACA - Honolulu p21-22 Awards of Medals p25-26 Meetings of Interest p27 Crystallography News December 2006 Contents From the President . 2 Council Members . 3 BCA From the Editor . 4 Administrative Office, Elaine Fulton, From Professor P Dolding Beedle. 5 Northern Networking Events Ltd. Puzzle Corner . 6 1 Tennant Avenue, College Milton South, East Kilbride, Glasgow G74 5NA Peter Main - Honorary Fellow . 6 Scotland, UK Tel: + 44 1355 244966 Fax: + 44 1355 249959 BCA 2007 Meeting . .8-13 e-mail: [email protected] BCA 2007 Meeting Timetable . 14-15 CRYSTALLOGRAPHY NEWS is is published quarterly (March, June, September and December) by the ECM . 16-19 British Crystallographic Association, and printed by William Anderson and Sons Ltd, Glasgow. Text should Groups . 20 preferably be sent electronically as MSword documents (any version - .doc, .rtf or .txt files). Diagrams and ACA . 21-22 figures are most welcome, but please send them separately from text as .jpg, .gif, .tif, or .bmp files. Items may include technical articles, news about Books . 23 people (e.g. awards, honours, retirements etc.), reports on past meetings of interest to His Worship Moreton Moore ................................... 23 crystallographers, notices of future meetings, historical reminiscences, letters to the editor, book, hardware or Obituary: Desmond Cunningham . 24 software reviews. Please ensure that items for inclusion in the March 2007 issue are sent to the Editor to arrive before 25th January 2007. Awards of Medals . 25-26 Bob Gould 33 Charterhall Road IUCr Wins Award . -

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting. -

Do Androids Dream of Computer Music? Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017

Do Androids Dream of Computer Music? Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017 Hosted by Elder Conservatorium of Music, The University of Adelaide. September 28th to October 1st, 2017 Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017, Adelaide, South Australia Keynote Speaker: Professor Takashi Ikegami Published by The Australasian University of Tokyo Computer Music Association Paper & Performances Jury: http://acma.asn.au Stephen Barrass September 2017 Warren Burt Paul Doornbusch ISSN 1448-7780 Luke Dollman Luke Harrald Christian Haines All copyright remains with the authors. Cat Hope Robert Sazdov Sebastian Tomczak Proceedings edited by Luke Harrald & Lindsay Vickery Barnabas Smith. Ian Whalley Stephen Whittington All correspondence with authors should be Organising Committee: sent directly to the authors. Stephen Whittington (chair) General correspondence for ACMA should Michael Ellingford be sent to [email protected] Christian Haines Luke Harrald Sue Hawksley The paper refereeing process is conducted Daniel Pitman according to the specifications of the Sebastian Tomczak Australian Government for the collection of Higher Education research data, and fully refereed papers therefore meet Concert / Technical Support Australian Government requirements for fully-refereed research papers. Daniel Pitman Michael Ellingford Martin Victory With special thanks to: Elder Conservatorium of Music; Elder Hall; Sud de Frank; & OzAsia Festival. DO ANDROIDS DREAM OF COMPUTER MUSIC? COMPUTER MUSIC IN THE AGE OF MACHINE