Do Androids Dream of Computer Music? Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Music Conference 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Nuevo DOOM Eternal, Ya Disponible Para Las Principales Plataformas

El nuevo DOOM Eternal, ya disponible para las principales plataformas Bethesda Softworks®, una empresa de ZeniMax® Media, ha anunciado que ya está disponible DOOM® Eternal para Xbox One, el sistema de entretenimiento informático PlayStation 4, PC y Google Stadia, tanto en versión digital como en tiendas físicas de todo el mundo. DOOM Eternal, un título desarrollado por id Software, recibió los premios al mejor juego de acción y el mejor juego para PC en el E3 2019, y ha aparecido en más de 350 listas con los juegos más deseados de 2020. Es la secuela directa de DOOM (2016), ganador del premio al Mejor juego de acción de 2016 en los Game Awards. “DOOM Eternal es el juego más ambicioso que nuestro estudio haya creado nunca —ha declarado Marty Stratton, productor ejecutivo de id Software—.La magnitud y la escala de la campaña y del modo BATTLEMODE son fieles testimonios de la pasión y el talento de toda la gente que trabaja en id Software. Nos lo hemos pasado en grande desarrollandoDOOM Eternal y estamos deseando que los jugadores puedan participar de la emoción de esta épica aventura”. Imagen promocional del nuevo DOOM DOOM ETERNAL ofrece a los jugadores un rompecabezas de combate agresivo y exigente en el que deben dominar nuevas armas y habilidades en el mayor, más profundo y más vertiginoso título de la historia de la saga. Con el motor idTech® 7 y una fabulosa banda sonora compuesta por Mick Gordon, el juego toma todo cuanto gustó a los jugadores en DOOM (2016), y le añade un sistema de combate aún más refinado, demonios nuevos y clásicos, un potentísimo y novedoso arsenal y mundos increíbles nunca vistos hasta la fecha. -

Kingpin, Vous Devrez Insérer Le CD Du Jeu Dans Votre Lecteur De CD-ROM Et Suivre 2) Abaisser La Qualité Des Effets Sonores

A LIRE AVANT TOUTE UTILISATION D’UN JEU VIDEO PAR VOUS-MEME OU PAR VOTRE ENFANT. I – Précautions à prendre dans tous les cas pour l’utilisation d’un jeu vidéo Evitez de jouer si vous êtes fatigué ou si vous manquez de sommeil. Assurez-vous que vous jouez dans une pièce bien éclairée en modérant la luminosité de votre écran. Lorsque vous utilisez un jeu vidéo susceptible d’être connecté à un écran, jouez à bonne distance de cet écran de télévision et aussi loin que le permet le cordon de raccordement. Guide Stratégique de Kingpin En cours d’utilisation, faites des pauses de dix à quinze minutes toutes les heures. II. – Avertissement sur l’épilepsie Pour devenir Certaines personnes sont susceptibles de faire des crises d’épilepsie comportant, le cas échéant, des pertes de conscience à la vue, notamment, de certains types de stimulations lumineuses fortes : succession rapide , d’images ou répétition de figures géométriques simples, d’éclairs ou d’explosions. Ces personnes s’exposent Kingpin à des crises lorsqu’elles jouent à certains jeux vidéo comportant de telles stimulations, alors même qu’elles n’ont pas d’antécédent médical ou n’ont jamais été sujettes elles-mêmes à des crises d’épilepsie. causez vite et Si vous-même ou un membre de votre famille avez déjà présenté des symptômes liés à l’épilepsie (crise ou perte de conscience) en présence de stimulations lumineuses, consultez votre médecin avant toute bien, et tirez utilisation. Les parents se doivent également d’être particulièrement attentifs à leurs enfants lorsqu’ils jouent avec des mieux encore. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

JMCS Newspaper.1

School IT John Muir Charter GR CCC Pomona Volume 1, Issue 1 November 2008 California Conservation Corps—Pomona Satellite DOWN UNDER, AS SEEN BY JOSH BEHRENS This month’s article is about none other than our esteemed Red Hat, Josh Behrens. Josh has recently returned from a trip to In this Issue: Australia. Josh left on Au- Australia; Josh Behrens gust 17th, and returned a Student Spotlight few weeks ago on October 17th. While asking him Spotlight on Staff; Lisa about his time there, the May subject of food came up, CORPSMEMBER SPOTLIGHT Music Review and we had to ask him what was the most exotic Malinda Allen Gaming Review or rather weird object he Random Photo ate. Josh gave us 2 an- Malinda Allen started here at the Pomona Satellite after having spent almost a year at the San Francisco Conser- Fire-Bag Checklist swers, the first being “Vegemite” Which is a pea- vation Corps. Malinda is almost finished with her High Monrovia Haunted Trail nut butter like spread that School graduation requirements and plans on attending Poetry Corner is actually made of yeast Community College. With an engaging personality and extract He also mentioned an infectious sense of humor, it is easy to see why Ma- Hard at Work... kangaroo meat which he linda is well regarded by her co-workers.. ∗ John Muir Charter School said was very lean and ten- Malinda is a loyal friend who cares deeply about social students work an 8-hour der and he said “it was the issues, including the environment. day “on the grade”. -

The Perceptual Attraction of Pre-Dominant Chords 1

Running Head: THE PERCEPTUAL ATTRACTION OF PRE-DOMINANT CHORDS 1 The Perceptual Attraction of Pre-Dominant Chords Jenine Brown1, Daphne Tan2, David John Baker3 1Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University 2University of Toronto 3Goldsmiths, University of London [ACCEPTED AT MUSIC PERCEPTION IN APRIL 2021] Author Note Jenine Brown, Department of Music Theory, Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA; Daphne Tan, Faculty of Music, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada; David John Baker, Department of Computing, Goldsmiths, University of London, London, United Kingdom. Corresponding Author: Jenine Brown, Peabody Institute of The John Hopkins University, 1 E. Mt. Vernon Pl., Baltimore, MD, 21202, [email protected] 1 THE PERCEPTUAL ATTRACTION OF PRE-DOMINANT CHORDS 2 Abstract Among the three primary tonal functions described in modern theory textbooks, the pre-dominant has the highest number of representative chords. We posit that one unifying feature of the pre-dominant function is its attraction to V, and the experiment reported here investigates factors that may contribute to this perception. Participants were junior/senior music majors, freshman music majors, and people from the general population recruited on Prolific.co. In each trial four Shepard-tone sounds in the key of C were presented: 1) the tonic note, 2) one of 31 different chords, 3) the dominant triad, and 4) the tonic note. Participants rated the strength of attraction between the second and third chords. Across all individuals, diatonic and chromatic pre-dominant chords were rated significantly higher than non-pre-dominant chords and bridge chords. Further, music theory training moderated this relationship, with individuals with more theory training rating pre-dominant chords as being more attracted to the dominant. -

Doom.Bethesda.Net

PUBLISHER: Bethesda Softworks DEVELOPER: id Software RELEASE DATE: 22nd November 2019 PLATFORM: Xbox One/PlayStation 4/PC/Nintendo Switch GENRE: First-Person Shooter GAME DESCRIPTION: Developed by id Software, DOOM® Eternal™ is the direct sequel to DOOM®, winner of The Game Awards’ Best Action Game of 2016. Experience the ultimate combination of speed and power as you rip-and-tear your way across dimensions with the next leap in push-forward, first-person combat. Powered by idTech 7 and set to an all-new pulse- pounding soundtrack composed by Mick Gordon, DOOM Eternal puts you in control of the unstoppable DOOM Slayer as you blow apart new and classic demons with powerful weapons in unbelievable and never-before-seen worlds. As the DOOM Slayer, you return to find Earth has suffered a demonic invasion. Raze Hell and discover the Slayer’s origins and his enduring mission to rip and tear…until it is done. FEATURES: Slayer Threat Level at Maximum Gain access to the latest demon-killing tech with the DOOM Slayer’s advanced Praetor Suit, including a shoulder- mounted flamethrower and the retractable wrist-mounted DOOM Blade. Upgraded guns and mods, such as the Super Shotgun’s new distance-closing Meat Hook attachment, and abilities like the Double Dash make you faster, stronger, and more versatile than ever. Unholy Trinity You can’t kill demons when you’re dead, and you can’t stay alive without resources. Take what you need from your enemies: Glory kill for extra health, incinerate for armor, and chainsaw demons to stock up on ammo. -

Martin Stig Anderson

MARTIN STIG ANDERSON SELECTED CREDITS WOLFENSTEIN: YOUNGBLOOD (MachineGames) (2019) CONTROL (Remedy Entertainment) (2019) SHADOW OF THE TOMB RAIDER (Eidos-Montréal) (2018) WOLFENSTEIN II: THE NEW COLOSSUS (MachineGames) (2017) INSIDE (Playdead) (2016) BIOGRAPHY Martin Stig Andersen is a Danish composer best known for his award-winning work within video games. In 2009 he created the audio for Playdead’s video game ‘Limbo’ which won Outstanding Achievement in Sound Design at the InteractiVe Achievement Awards, the IndieCade Sound Award 2010, and was nominated for Use of Audio at the BAFTA Video Games Awards 2011. Following the release of ‘Limbo’, Andersen created and directed the audio for Playdead’s ‘Inside’ which won Best Audio at the Game DeVelopers Choice Awards and has receiVed music and sound design nominations at The Game Awards, The InteractiVe AchieVement Awards and the BAFTA Video Games awards amongst others. In 2017 he composed the score for MachineGames' Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus alongside Mick Gordon which receiVed nominations at The InteractiVe AchieVement Awards, New York Game Awards amongst others. With a background in the fields of acousmatic music, sound installations, electroacoustic performance, and Video art, Martin is known for exploring dynamic relationship between sound and image as a means to reVealing new stories and emotional experiences. His work is often characterized by blurring the dividing line between music and sound design and while he coVers the whole spectrum he is also collaborating with other composers and sound designers in creating unified sound worlds. Being a sought-after speaker, he frequently lectures at conferences such as GDC, DeVelop, and the School of Sound in London. -

Take a Road Trip Through Hell in EA and Grasshopper Manufacture's Psycho-Punk Action Thriller Shadows of the Damned

Take a Road Trip Through Hell in EA and Grasshopper Manufacture's Psycho-Punk Action Thriller Shadows of the Damned REDWOOD CITY, Calif.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Electronic Arts Inc. (NASDAQ:ERTS) and legendary Japanese developer Grasshopper Manufacture today announced that Shadows of the Damned™ is now available at retail stores across North America. Created by renowned developers Suda51 (director of No More Heroes), Shinji Mikami (director of Resident Evil) and music composer Akira Yamaoka (sound director of Silent Hill), Shadows of the Damned combines visceral, grindhouse-style action with a psychologically twisted setting to provide a truly one-of-a-kind vision of hell, and is already receiving worldwide critical acclaim, with Game Informer giving it 9.25 out and 10, stating "Shadows of the Damned is a road trip to Hell well worth taking." GamesMaster UK also says that the game is "a kitsch, punk rock and roll assault on the senses," scoring it 90% out of 100%. Heavily influenced by grindhouse-style projects, Shadows of the Damned takes gamers on a demented journey through a tortured underworld where death and destruction are around every corner. Playing as professional demon hunter Garcia Hotspur, gamers must harness the power of the light to save Paula — the love of his life — from the Lord of Demons. Manipulating this balance of light versus dark gameplay in different settings and scenarios, gamers can discover new ways to defeat vicious enemies and solve mind-boggling puzzles. Along this hellish adventure, players will be aided by Johnson, a former demon with the ability to transform into an arsenal of upgradeable, supernatural weapons, giving Garcia the power to rip apart the forces of the damned and ultimately protect what he loves most. -

Quake II Readme File

Quake II ReadMe File CONTENTS I. Story II. Installation III. Setup a. Goal of the Game b. Game Structure c. Main Menu d. Game e. Multiplayer Menu Selection f. Video Menu Selection g. Options h. On-Screen Information During Gameplay IV. Getting Around Stroggos a. Movement b. Dying V. Multiplayer Quake II a. Join Network Server b. Start Network Server c. Player Setup VI. TCM Intel Brief: Classified VII. Technical Information a. System Requirements b. Release Notes c. About Direct X d. What is OpenGL? - About the Quake II 3D Accelerated Engine e. More on Quake II Video VIII. Customer Support IX. Credits ==================== == I. The Story == ==================== Long shadows claw desperately away from your dusty combat boots, fueled by the relentless sun of a late Texas afternoon. Shading your eyes against the glare, you squint for the thousandth time at the line of soldiers ahead of you. It stretches on endlessly across the rubble, disappearing at last into the cool shadows of a troop carrier. Soon you'll walk up the ramp into the ship, climb into your one-man cocoon, tear through the interplanetary gateway, and smash down light-years away from the blowing sand and blasted ruins that surround the Dallas-Metro crater. "What the hell is taking so long?!" you snarl, slamming the battered barrel of your side arm, the blaster, against your scarred palm. "I've waited long enough. Time to kick some Strogg ass." Slightly rocking back and forth under the sweltering August sun, you spit out of the side of your mouth, rub your eyes, and think back to the day when the wretched creatures first attaced. -

Elliot Levey

Elliot Levey Agents Ruth Young Associate Agent Phoebe Trousdell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Lauren Morgan [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Assistant Alex Campbell [email protected] +44 (0)20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company MURDER ON THE Rabbi Kenneth Branagh Twentieth Century Fox ORIENT EXPRESS DENIAL Roger Levey Mick Jackson Krasnoff / Foster Entertainment FALLEN Dr. Watkins Scott Hicks Lotus Entertainment/ Mayhem Pictures THE MASTER OF YORK Menachem Kieron Quirke Eagle Lion Monster Films FLORENCE FOSTER Edgar Booth Stephen Frears Florence Film Ltd JENKINS Cunningham Jr United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE LADY IN THE VAN Director Nicholas Hytner Van Production Ltd. SPOOKS Philip Emmerson Bharat Nalluri Shine Pictures & Kudos PHILOMENA Alex Stephen Frears Lost Child Limited THE WALL Stephen Cam Christiansen National film Board of Canada THE QUEEN Stephen Frears Granada FILTH AND WISDOM Madonna HSI London SONG OF SONGS Isaac Josh Appignanesi AN HOUR IN PARADISE Benjamin Jan Schutte BOOK OF JOHN Nathanael Philip Saville DOMINOES Ben Mirko Seculic JUDAS AND JESUS Eliakim Charles Carner Paramount QUEUES AND PEE Ben Despina Catselli Pinhead Films JASON AND THE Canthus Nick Willing Hallmark ARGONAUTS JESUS Tax Collector Roger Young Andromeda Prods DENIAL Roger Levey Denial LTD Television Production Character Director Company -

Videojuegos, Cultura Y Sociedad

PRESURA VIDEOJUEGOS, CULTURA Y SOCIEDAD NÚMERO XVII MÚSICA Y VIDEOJUEGOS El número XVII, XVII estilo y dirigida a un ni- números de Presura en cho, no aspira a ser un un año. Un número que éxito de masas, pero que no es redondo pero que cada vez seamos más y para mi significa muchí- más es algo a lo que no simo, hemos alcanzado estamos acostumbrados la mayoría de edad. El y nos encanta. Como proyecto no para de cre- sabéis no conseguimos PRESURA cer, estas semanas he- ningún beneficio econó- VIDEOJUEGOS, CULTURA Y SOCIEDAD mos retomado, con éxito, mico con Presura, voso- la actividad en la web. tros, como decía La Cabra Nuestras redes sociales Mecánica, sois nuestra siguen creciendo y todo única riqueza. Sin más, esto es gracias a voso- disfrutad de nuestra ma- tros. Una revista como yoría de edad. Bienveni- Presura, tan ceñida a un dos de nuevo a Presura. ALBERTO VENEGAS RAMOS. Profesor de Histo- al Shams o Témpora Ma- ria en la educación se- gazine y estudiante del cundaria, estudiante de máster Estudios Árabes Antropología Social e e Islámicos Contempo- PRESENTACIÓN investigador en temas ráneos de la Universidad relacionados con la iden- Autónoma de Madrid. tidad en el mundo islá- Colabor de medios como mico además de redactor FS Gamer, CTXT, eldiaro. MÚSICA Y VIDEOJUEGOS. en páginas como Baab es o Akihabara Blues. [email protected] NÚMERO XVII. @albertoxvenegas ATRAVESANDO LA BRECHA VIRTUAL: MÚSICA, VIDEOJUEGOS Y REALIDAD AUMENTADA DE ROBERTO CARLOS FERNÁNDEZ CONTENIDOS: SÁNCHEZ. PÁGINA 16 TRIBUNA - PÁGINA 10 LA MÚSICA Y EL VIDEOJUEGO ABSOLUTO, DE ÍKER GARCÍA ROSO. -

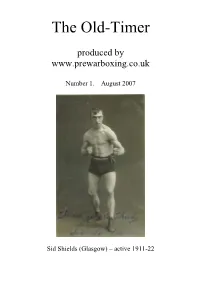

The Old-Timer

The Old-Timer produced by www.prewarboxing.co.uk Number 1. August 2007 Sid Shields (Glasgow) – active 1911-22 This is the first issue of magazine will concentrate draw equally heavily on this The Old-Timer and it is my instead upon the lesser material in The Old-Timer. intention to produce three lights, the fighters who or four such issues per year. were idols and heroes My prewarboxing website The main purpose of the within the towns and cities was launched in 2003 and magazine is to present that produced them and who since that date I have historical information about were the backbone of the directly helped over one the many thousands of sport but who are now hundred families to learn professional boxers who almost completely more about their boxing were active between 1900 forgotten. There are many ancestors and frequently and 1950. The great thousands of these men and they have helped me to majority of these boxers are if I can do something to learn a lot more about the now dead and I would like preserve the memory of a personal lives of these to do something to ensure few of them then this boxers. One of the most that they, and their magazine will be useful aspects of this exploits, are not forgotten. worthwhile. magazine will be to I hope that in doing so I amalgamate boxing history will produce an interesting By far the most valuable with family history so that and informative magazine. resource available to the the articles and features The Old-Timer will draw modern boxing historian is contained within are made heavily on the many Boxing News magazine more interesting.