Biography Cast in Irony: Caveats, Stylization, and Indeterminacy in the Biographical History Plays of Tom Stoppard and Michael Frayn, Written by Christopher M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Asolo Rep Continues Its 60Th Season with NOISES OFF Directed By

NOISES OFF Page 1 of 7 **FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE** February 25, 2019 Asolo Rep Continues its 60th Season with NOISES OFF Directed by Comedic Broadway Veteran Don Stephenson March 20 - April 20 (SARASOTA, February 25, 2019) — Asolo Rep continues its celebration of 60 years on stage with Tony Award®-winner Michael Frayn's rip-roaringly hilarious play NOISES OFF, one of the most celebrated farces of all time. Directed by comedic Broadway veteran Don Stephenson, NOISES OFF previews March 20 and 21, opens March 22 and runs through April 20 in rotating repertory in the Mertz Theatre, located in the FSU Center for the Performing Arts. A comedy of epic proportions, NOISES OFF has been the laugh-until-you-cry guilty pleasure of audiences for decades. With opening night just hours away, a motley company of actors stumbles through a frantic, final rehearsal of the British sex farce Nothing On, and things could not be going worse. Lines are forgotten, love triangles are unraveling, sardines are flying everywhere, and complete pandemonium ensues. Will the cast pull their act together on stage even if they can't behind the scenes? “With Don Stephenson, an extraordinary comedic actor and director at the helm, this production of NOISES OFF is bound to be one of the funniest theatrical experiences we have ever presented,” said Asolo Rep Producing Artistic Director Michael Donald Edwards. “I urge the Sarasota community to take a break and escape to NOISES OFF, a joyous celebration of the magic of live theatre.” Don Stephenson's directing work includes Titanic (Lincoln Center, MUNY), Broadway Classics (Carnegie Hall),Of Mice and Manhattan (Kennedy Center), A Comedy of Tenors (Paper Mill Playhouse) and more. -

NOV–DEC 2016 SEASON 50, ISSUE 3 Untitled-2 1

SAN FRANCISCO’S PREMIER NONPROFIT THEATER COMPANY NOV–DEC 2016 SEASON 50, ISSUE 3 “ City National helps keep my financial life in tune.” So much of my life is always shifting; a different city, a different piece of music, a different ensemble. I need people who I can count on to help keep my financial life on course so I can focus on creating and sharing the “adventures” of classical music. City National shares my passion and is instrumental in helping me bring classical music to audiences all over the world. They enjoy being a part of what I do and love. That is the essence of a successful relationship. City National is The way up® for me. Michael Tilson Thomas Conductor, Educator and Composer Hear Michael’s complete story at Findyourwayup.com/Tuned2SF Find your way up.SM Call (866) 618-5242 to speak with a personal banker. 16 City National Bank 16 City National 0 ©2 City National Personal Banking CNB MEMBER FDIC Untitled-2 1 8/10/16 12:13 PM B:8.625” T:8.375” S:7.375” B:11.125” T:10.875” S:9.875” We care for the city that helped you start a new chapter. Our kidney and transplant programs have higher than expected outcomes than any other hospital in the country. When you call this city home, you call CPMC your hospital. cpmc2020.org EAP full-page template.indd 1 10/7/16 4:47 PM 40775 Version:01 09-02-16 hr 40775_SFEncore_BStore 1 SF Ballet-Encore_Bookstore Saved at 09-02-2016 from by Printed At None Job info Approvals Fonts & Images Job 40775 Art Director Fonts Client Sutter Health Copywriter Helvetica Neue LT Std (75 Bold, 45 Light), Media Type Magazine Account Mgr Helvetica Neue (Bold) Live 7.375” x 9.875” Studio Artist Trim 8.375” x 10.875” Proofreader Images Bleed 8.625” x 11.125” Pubs SF Ballet Notes Inks SF Encore Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black None November 2016 Volume 15, No. -

The Best According To

Books | The best according to... http://books.guardian.co.uk/print/0,,32972479299819,00.html The best according to... Interviews by Stephen Moss Friday February 23, 2007 Guardian Andrew Motion Poet laureate Choosing the greatest living writer is a harmless parlour game, but it might prove more than that if it provokes people into reading whoever gets the call. What makes a great writer? Philosophical depth, quality of writing, range, ability to move between registers, and the power to influence other writers and the age in which we live. Amis is a wonderful writer and incredibly influential. Whatever people feel about his work, they must surely be impressed by its ambition and concentration. But in terms of calling him a "great" writer, let's look again in 20 years. It would be invidious for me to choose one name, but Harold Pinter, VS Naipaul, Doris Lessing, Michael Longley, John Berger and Tom Stoppard would all be in the frame. AS Byatt Novelist Greatness lies in either (or both) saying something that nobody has said before, or saying it in a way that no one has said it. You need to be able to do something with the English language that no one else does. A great writer tells you something that appears to you to be new, but then you realise that you always knew it. Great writing should make you rethink the world, not reflect current reality. Amis writes wonderful sentences, but he writes too many wonderful sentences one after another. I met a taxi driver the other day who thought that. -

PHILIP ROTH and the STRUGGLE of MODERN FICTION by JACK

PHILIP ROTH AND THE STRUGGLE OF MODERN FICTION by JACK FRANCIS KNOWLES A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) July 2020 © Jack Francis Knowles, 2020 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, the dissertation entitled: Philip Roth and The Struggle of Modern Fiction in partial fulfillment of the requirements submitted by Jack Francis Knowles for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Examining Committee: Ira Nadel, Professor, English, UBC Supervisor Jeffrey Severs, Associate Professor, English, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Michael Zeitlin, Associate Professor, English, UBC Supervisory Committee Member Lisa Coulthard, Associate Professor, Film Studies, UBC University Examiner Adam Frank, Professor, English, UBC University Examiner ii ABSTRACT “Philip Roth and The Struggle of Modern Fiction” examines the work of Philip Roth in the context of postwar modernism, tracing evolutions in Roth’s shifting approach to literary form across the broad arc of his career. Scholarship on Roth has expanded in both range and complexity over recent years, propelled in large part by the critical esteem surrounding his major fiction of the 1990s. But comprehensive studies of Roth’s development rarely stray beyond certain prominent subjects, homing in on the author’s complicated meditations on Jewish identity, a perceived predilection for postmodern experimentation, and, more recently, his meditations on the powerful claims of the American nation. This study argues that a preoccupation with the efficacies of fiction—probing its epistemological purchase, questioning its autonomy, and examining the shaping force of its contexts of production and circulation— roots each of Roth’s major phases and drives various innovations in his approach. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

E.M. Parry Designer

E.M. Parry Designer E.M. Parry is a transgender, trans-disciplinary artist and theatre- maker, best known for theatre design, specialising in work which centres queer bodies and narratives. They are an Associate Artist at Shakespeare’s Globe, a Linbury Prize Finalist, winner of the Jocelyn Herbert Award, and shared an Olivier Award for Outstanding Achievement as part of the team behind Rotterdam, for which they designed set and costumes. Agents Dan Usztan Assistant [email protected] Charlotte Edwards 0203 214 0873 [email protected] 0203 214 0924 Credits In Development Production Company Notes DORIAN Reading Rep Dir. Owen Horsley 2021 Written by Phoebe Eclair-Powell and Owen Horsley Theatre Production Company Notes STAGING PLACES: UK Victoria and Albert Museum Designs included in exhibition DESIGN FOR PERFORMANCE 2019 AS YOU LIKE IT Shakespeare's Globe Revival of 2018 production 2019 United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE STRANGE New Vic Theatre Dir. Anna Marsland UNDOING OF By David Grieg PRUDENCIA HART 2019 ROTTERDAM Hartshorn Hook UK tour of Olivier Award-winning production 2019 TRANSLYRIA Sogn og Fjordane Teater, Dir. Frode Gjerlow 2019 Norway By William Shakespeare & Frode Gjerlow GRIMM TALES Unicorn Theatre Dir. Kirsty Housley 2018 Adapted from Philip Pullman's Grimm Tales by Philip Wilson SKETCHING Wilton's Music Hall Dir. Thomas Hescott 2018 By James Graham AS YOU LIKE IT Shakespeare's Globe Dir. Federay Holmes and Elle While 2018 By William Shakespeare HAMLET Shakespeare's Globe Dir. -

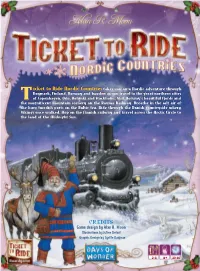

Rules EN 2015 TTR2 Rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2

[T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:51 Page2 icket to Ride Nordic Countries takes you on a Nordic adventure through Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden as you travel to the great northern cities T of Copenhagen, Oslo, Helsinki and Stockholm. Visit Norway's beautiful fjords and the magnificent mountain scenery on the Rauma Railway. Breathe in the salt air of the busy Swedish ports on the Baltic Sea. Ride through the Danish countryside where Vikings once walked. Hop-on the Finnish railway and travel across the Arctic Circle to the land of the Midnight Sun. CREDITS Game design by Alan R. Moon Illustrations by Julien Delval Graphic Design by Cyrille Daujean 2-3 8+ 30-60’ [T2RNordic] rules EN 2015_TTR2 rules Nordic EN 18/05/15 15:52 Page3 Components 1 Globetrotter Bonus card u 1 Board map of Scandinavian train routes for the most completed tickets u 120 Colored Train cars (40 each in 3 different colors, plus a few spare) 46 Destination u 157 Illustrated cards: Ticket cards 110 Train cards : 12 of each color, plus 14 Locomotives ∫ ∂ u 3 Wooden Scoring Markers (1 for each player matching the train colors) u 1 Rules booklet Setting up the Game Place the board map in the center of the table. Each player takes a set of 40 Colored Train Cars along with its matching Scoring Marker. Each player places his Scoring Marker on the starting π location next to the 100 number ∂ on the Scoring Track running along the map's border. Throughout the game, each time a player scores points, he will advance his marker accordingly. -

Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature

Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature By Derek M. Ettensohn M.A., Brown University, 2012 B.A., Haverford College, 2006 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at Brown University PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND MAY 2014 © Copyright 2014 by Derek M. Ettensohn This dissertation by Derek M. Ettensohn is accepted in its present form by the Department of English as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Date ___________________ _________________________ Olakunle George, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date ___________________ _________________________ Timothy Bewes, Reader Date ___________________ _________________________ Ravit Reichman, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date ___________________ __________________________________ Peter Weber, Dean of the Graduate School iii Abstract of “Globalism, Humanitarianism, and the Body in Postcolonial Literature” by Derek M. Ettensohn, Ph.D., Brown University, May 2014. This project evaluates the twinned discourses of globalism and humanitarianism through an analysis of the body in the postcolonial novel. In offering celebratory accounts of the promises of globalization, recent movements in critical theory have privileged the cosmopolitan, transnational, and global over the postcolonial. Recognizing the potential pitfalls of globalism, these theorists have often turned to transnational fiction as supplying a corrective dose of humanitarian sentiment that guards a global affective community against the potential exploitations and excesses of neoliberalism. While authors such as Amitav Ghosh, Nuruddin Farah, and Rohinton Mistry have been read in a transnational, cosmopolitan framework––which they have often courted and constructed––I argue that their theorizations of the body contain a critical, postcolonial rejoinder to the liberal humanist tradition that they seek to critique from within. -

Joyce's Jewish Stew: the Alimentary Lists in Ulysses

Colby Quarterly Volume 31 Issue 3 September Article 5 September 1995 Joyce's Jewish Stew: The Alimentary Lists in Ulysses Jaye Berman Montresor Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Quarterly, Volume 31, no.3, September 1995, p.194-203 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Montresor: Joyce's Jewish Stew: The Alimentary Lists in Ulysses Joyce's Jewish Stew: The Alimentary Lists in Ulysses by JAYE BERMAN MONTRESOR N THEIR PUN-FILLED ARTICLE, "Towards an Interpretation ofUlysses: Metonymy I and Gastronomy: A Bloom with a Stew," an equally whimsical pair ofcritics (who prefer to remain pseudonymous) assert that "the key to the work lies in gastronomy," that "Joyce's overriding concern was to abolish the dietary laws ofthe tribes ofIsrael," and conclude that "the book is in fact a stew! ... Ulysses is a recipe for bouillabaisse" (Longa and Brevis 5-6). Like "Longa" and "Brevis'"interpretation, James Joyce's tone is often satiric, and this is especially to be seen in his handling ofLeopold Bloom's ambivalent orality as a defining aspect of his Jewishness. While orality is an anti-Semitic assumption, the source ofBloom's oral nature is to be found in his Irish Catholic creator. This can be seen, for example, in Joyce's letter to his brother Stanislaus, penned shortly after running off with Nora Barnacle in 1904, where we see in Joyce's attention to mealtimes the need to present his illicit sexual relationship in terms of domestic routine: We get out ofbed at nine and Nora makes chocolate. -

Performing History Studies in Theatre History & Culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY

Performing history studies in theatre history & culture Edited by Thomas Postlewait Performing HISTORY theatrical representations of the past in contemporary theatre Freddie Rokem University of Iowa Press Iowa City University of Iowa Press, Library of Congress Iowa City 52242 Cataloging-in-Publication Data Copyright © 2000 by the Rokem, Freddie, 1945– University of Iowa Press Performing history: theatrical All rights reserved representations of the past in Printed in the contemporary theatre / by Freddie United States of America Rokem. Design by Richard Hendel p. cm.—(Studies in theatre http://www.uiowa.edu/~uipress history and culture) No part of this book may be repro- Includes bibliographical references duced or used in any form or by any and index. means, without permission in writing isbn 0-87745-737-5 (cloth) from the publisher. All reasonable steps 1. Historical drama—20th have been taken to contact copyright century—History and criticism. holders of material used in this book. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), The publisher would be pleased to make in literature. 3. France—His- suitable arrangements with any whom tory—Revolution, 1789–1799— it has not been possible to reach. Literature and the revolution. I. Title. II. Series. The publication of this book was generously supported by the pn1879.h65r65 2000 University of Iowa Foundation. 809.2Ј9358—dc21 00-039248 Printed on acid-free paper 00 01 02 03 04 c 54321 for naama & ariel, and in memory of amitai contents Preface, ix Introduction, 1 1 Refractions of the Shoah on Israeli Stages: -

Savoring the Classical Tradition in Drama

SAVORING THE CLASSICAL TRADITION IN DRAMA MEMORABLE PRESENTATIONS BY THE SHAKESPEARE GUILD I N P R O U D COLLABORATION WIT H THE NATIONAL ARTS CLUB THE PLAYERS, NEW YORK CITY THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION JIM DALE ♦ Friday, January 24 In the 1950s and ’60s JIM DALE was known primarily as a singer and songwriter, with such hits as Oscar nominee “Georgy Girl” to his credit. Meanwhile he was earning plaudits as a film and television comic, with eleven Carry On features that made him a NATIONAL ARTS CLUB household name in Britain. Next came stage roles like 15 Gramercy Park South Autolycus and Bottom with Laurence Olivier’s National Manhattan Theatre Company, and Fagin in Cameron Mackintosh’s PROGRAM AT 6:00 P.M. Oliver. In 1980 he collected a Tony Award for his title Admission Free, But role in Barnum. Since then he has been nominated for Reservations Requested Tony, Drama Desk, and other honors for his work in such plays as Candide, Comedians, Joe Egg, Me and My Girl, and Scapino. As if those accolades were not enough, he also holds two Grammy Awards and ten Audie Awards as the “voice” of Harry Potter. We look forward to a memorable evening with one of the most versatile performers in entertainment history. RON ROSENBAUM ♦ Monday, March 23 Most widely known for Explaining Hitler, a 1998 best-seller that has been translated into ten languages, RON ROSENBAUM is also the author of The Secret Parts of Fortune, Those Who Forget the Past, and How the End Begins: The Road to a Nuclear World War III. -

William and Mary Theatre Main Stage Productions

WILLIAM AND MARY THEATRE MAIN STAGE PRODUCTIONS 1926-1927 1934-1935 1941-1942 The Goose Hangs High The Ghosts of Windsor Park Gas Light Arms and the Man Family Portrait 1927-1928 The Romantic Age The School for Husbands You and I The Jealous Wife Hedda Gabler Outward Bound 1935-1936 1942-1943 1928-1929 The Unattainable Thunder Rock The Enemy The Lying Valet The Male Animal The Taming of the Shrew The Cradle Song *Bach to Methuselah, Part I Candida Twelfth Night *Man of Destiny Squaring the Circle 1929-1930 1936-1937 The Mollusc Squaring the Circle 1943-1944 Anna Christie Death Takes a Holiday Papa is All Twelfth Night The Gondoliers The Patriots The Royal Family A Trip to Scarborough Tartuffe Noah Candida 1930-1931 Vergilian Pageant 1937-1938 1944-1945 The Importance of Being Earnest The Night of January Sixteenth Quality Street Just Suppose First Lady Juno and the Paycock The Merchant of Venice The Mikado Volpone Enter Madame Liliom Private Lives 1931-1932 1938-1939 1945-1946 Sun-Up Post Road Pygmalion Berkeley Square RUR Murder in the Cathedral John Ferguson The Pirates of Penzance Ladies in Retirement As You Like It Dear Brutus Too Many Husbands 1932-1933 1939-1940 1946-1947 Outward Bound The Inspector General Arsenic and Old Lace Holiday Kind Lady Arms and the Man The Recruiting Officer Our Town The Comedy of Errors Much Ado About Nothing Hay Fever Joan of Lorraine 1933-1934 1940-1941 1947-1948 Quality Street You Can’t Take It with You The Skin of Our Teeth Hotel Universe Night Must Fall Blithe Spirit The Swan Mary of Scotland MacBeth