Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Itcontents 9..22

INTERNATIONAL TABLES FOR CRYSTALLOGRAPHY Volume F CRYSTALLOGRAPHY OF BIOLOGICAL MACROMOLECULES Edited by MICHAEL G. ROSSMANN AND EDDY ARNOLD Advisors and Advisory Board Advisors: J. Drenth, A. Liljas. Advisory Board: U. W. Arndt, E. N. Baker, S. C. Harrison, W. G. J. Hol, K. C. Holmes, L. N. Johnson, H. M. Berman, T. L. Blundell, M. Bolognesi, A. T. Brunger, C. E. Bugg, K. K. Kannan, S.-H. Kim, A. Klug, D. Moras, R. J. Read, R. Chandrasekaran, P. M. Colman, D. R. Davies, J. Deisenhofer, T. J. Richmond, G. E. Schulz, P. B. Sigler,² D. I. Stuart, T. Tsukihara, R. E. Dickerson, G. G. Dodson, H. Eklund, R. GiegeÂ,J.P.Glusker, M. Vijayan, A. Yonath. Contributing authors E. E. Abola: The Department of Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research W. Chiu: Verna and Marrs McLean Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Institute, La Jolla, CA 92037, USA. [24.1] Biology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas 77030, USA. [19.2] P. D. Adams: The Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Department of Molecular J. C. Cole: Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge Biophysics and Biochemistry, Yale University, New Haven, CT 06511, USA. CB2 1EZ, England. [22.4] [18.2, 25.2.3] M. L. Connolly: 1259 El Camino Real #184, Menlo Park, CA 94025, USA. F. H. Allen: Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, 12 Union Road, Cambridge [22.1.2] CB2 1EZ, England. [22.4, 24.3] K. D. Cowtan: Department of Chemistry, University of York, York YO1 5DD, U. W. Arndt: Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Medical Research Council, Hills England. -

Kathleen Lonsdale

Edited by KATHLEEN LONSDALE PRICE 3/6 Quakers Visit Russia Ediled by KATHLEEN LONSDALE Published by the Eash West Reialions Group of the Frle/idt' Peace Cotn/tti.dee, Friends House, Euston Road, London, N. IK t. First Edition July 1952 Reprinted October 1952 QUAKERS VISIT RUSSIA Edited by KATHLEEN LONSDALE Declaration to Charles II, 1660 "JKe utterly deny all outward wars and strife, and fightings with outward weapons, for any end, or under any pretence whatever; this is our testimony to the whole world. The Spirit of Christ by which we are guided is not changeable, so as once to command us from a thing as evil and again to move unto it; and we certainly know and testify to the world, that the Spirit of Christ, which leads us into all Truth, will never move us to fight and war against any man with outward weapons, neither for the Kingdom of Christ nor for the Kingdoms of this world.” Message of Goodwill to AM Men, 1956 (frwd In Engltih, French, German and Jtustton') "In face of deepening fear and mutual distrust throughout the world, the Society of Friends (Quakers) is moved to declare goodwill to all men everywhere. Friends appeal for the avoidance of words and deeds that increase suspicion and ill- feeling, for renewed efforts at understanding and for positive attempts to build a true peace. They are convinced that reconciliation is possible. They hope that this simple word, translated into many tongues, may itself help to create the new spirit in which the resources of the world will be diverted from war dike purposes and applied to the welfare of mankind.” Hl CONTENTS Chapter 1. -

Edward M. Eyring

The Chemistry Department 1946-2000 Written by: Edward M. Eyring Assisted by: April K. Heiselt & Kelly Erickson Henry Eyring and the Birth of a Graduate Program In January 1946, Dr. A. Ray Olpin, a physicist, took command of the University of Utah. He recruited a number of senior people to his administration who also became faculty members in various academic departments. Two of these administrators were chemists: Henry Eyring, a professor at Princeton University, and Carl J. Christensen, a research scientist at Bell Laboratories. In the year 2000, the Chemistry Department attempts to hire a distinguished senior faculty member by inviting him or her to teach a short course for several weeks as a visiting professor. The distinguished visitor gets the opportunity to become acquainted with the department and some of the aspects of Utah (skiing, national parks, geodes, etc.) and the faculty discover whether the visitor is someone they can live with. The hiring of Henry Eyring did not fit this mold because he was sought first and foremost to beef up the graduate program for the entire University rather than just to be a faculty member in the Chemistry Department. Had the Chemistry Department refused to accept Henry Eyring as a full professor, he probably would have been accepted by the Metallurgy Department, where he had a courtesy faculty appointment for many years. Sometime in early 1946, President Olpin visited Princeton, NJ, and offered Henry a position as the Dean of the Graduate School at the University of Utah. Henry was in his scientific heyday having published two influential textbooks (Samuel Glasstone, Keith J. -

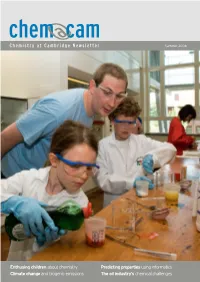

Enthusing Children About Chemistry Climate Change and Biogenic Emissions Predicting Properties Using Informatics the Oil Industr

Summer 2008 Enthusing children about chemistry Predicting properties using informatics Climate change and biogenic emissions The oil industry’s chemical challenges As I see it... So are you finding it increasingly diffi - Oil exploration doesn’t just offer a career for engineers – cult to attract good chemists? chemists are vital, too. Sarah Houlton spoke to Schlumberger’s It can be a challenge, yes. Many of the com - pany’s chemists are recruited here, and they Tim Jones about the crucial role of chemistry in the industry often move on to other sites such as Houston or Paris, but finding them in the first place can be a challenge. Maybe one reason is that the oil People don’t think of Schlumberger as We can’t rely on being able to find suitable industry doesn’t have the greatest profile in a chemistry-using company, but an chemistries in other industries, either, mainly chemistry, and people think it employs engi - engineering one. How important is because of the high temperatures and pressures neers, not chemists. But it’s something the chemistry in oil exploration? that we have to be able to work at. Typically, the upstream oil industry cannot manage without, It’s essential! There are many challenges for upper temperature norm is now 175°C, but even if they don’t realise it! For me, maintaining chemistry in helping to maintain or increase oil we’re increasingly looking to go over 200°C. – if not enhancing – our recruitment is perhaps production. It’s going to become increasingly For heavy oil, where we heat the oil up with one of the biggest issues we face. -

George De Hevesy in America

Journal of Nuclear Medicine, published on July 13, 2019 as doi:10.2967/jnumed.119.233254 George de Hevesy in America George de Hevesy was a Hungarian radiochemist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1943 for the discovery of the radiotracer principle (1). As the radiotracer principle is the foundation of all diagnostic and therapeutic nuclear medicine procedures, Hevesy is widely considered the father of nuclear medicine (1). Although it is well-known that he spent time at a number of European institutions, it is not widely known that he also spent six weeks at Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, in the fall of 1930 as that year’s Baker Lecturer in the Department of Chemistry (2-6). “[T]he Baker Lecturer gave two formal presentations per week, to a large and diverse audience and provided an informal seminar weekly for students and faculty members interested in the subject. The lecturer had an office in Baker Laboratory and was available to faculty and students for further discussion.” (7) There is also evidence that, “…Hevesy visited Harvard [University, Cambridge, MA] as a Baker Lecturer at Cornell in 1930…” (8). Neither of the authors of this Note/Letter was aware of Hevesy’s association with Cornell University despite our longstanding ties to Cornell until one of us (WCK) noticed the association in Hevesy’s biographical page on the official Nobel website (6). WCK obtained both his undergraduate degree and medical degree from Cornell in Ithaca and New York City, respectively, and spent his career in nuclear medicine. JRO did his nuclear medicine training at Columbia University and has subsequently been a faculty member of Weill Cornell Medical College for the last eleven years (with a brief tenure at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (affiliated with Cornell)), and is now the program director of the Nuclear Medicine residency and Chief of the Molecular Imaging and Therapeutics Section. -

AHMED H. ZEWAIL 26 February 1946 . 2 August 2016

AHMED H. ZEWAIL 26 february 1946 . 2 august 2016 PROCEEDINGS OF THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY VOL. 162, NO. 2, JUNE 2018 biographical memoirs t is often proclaimed that a stylist is someone who does and says things in memorable ways. From an analysis of his experimental Iprowess, his written contributions, his lectures, and even from the details of the illustrations he used in his published papers or during his lectures to scientific and other audiences, Ahmed Zewail, by this or any other definition, was a stylist par excellence. For more than a quarter of a century, I interacted with Ahmed (and members of his family) very regularly. Sometimes he and I spoke several times a week during long-distance calls. Despite our totally different backgrounds we became the strongest of friends, and we got on with one another like the proverbial house on fire. We collaborated scientifi- cally and we adjudicated one another’s work, as well as that of others. We frequently exchanged culturally interesting stories. We each relished the challenge of delivering popular lectures. In common with very many others, I deem him to be unforgettable, for a variety of different reasons. He was one of the intellectually ablest persons that I have ever met. He possessed elemental energy. He executed a succession of brilliant experiments. And, almost single-handedly, he created the subject of femtochemistry, with all its magnificent manifestations and ramifications. From the time we first began to exchange ideas, I felt a growing affinity for his personality and attitude. This was reinforced when I told him that, ever since I was a teenager, I had developed a deep interest in Egyptology and a love for modern Egypt. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Keeping the Promise: Phys Rev Completes Online Archive the Physical Review Be Explored

August/September 2001 NEWS Volume 10, No. 8 A Publication of The American Physical Society http://www.aps.org/apsnews Keeping the Promise: Phys Rev Completes Online Archive The Physical Review be explored. The earliest volumes institutions and others to link to Online Archive or of the journals can be examined at APS publications, both current ma- PRL Gets a PROLA is now com- length, in detail and at ease. Histo- terial and PROLA. Authors are also plete: every paper in rians and biographers can track the free to mount their Physical Review New Face every journal that APS expansion of the knowledge of papers on their own sites. has published since physics that took place over the PROLA is composed of scanned 1893 (excepting the previous century in Physical Review. images of the printed journals, op- present and past three Research published in Physical Re- tical character recognition (OCR) years, which are held view by any particular author or material, and a searchable separately for current group or institution can be col- richly-tagged XML bibliographic subscribers) mounted lected and perused with a search database. Each year, another year online in a friendly, of PROLA and a second search of of this material is added to PROLA Bob Kelly/APS powerful, fully search- PROLA team at APS Editorial Office in Ridge, NY: Louise current content. Journalists can ac- from the current subscription con- able system. The project Bogan; Paul Dlug; Mark Doyle, Project Manager; Maxim cess physics Nobel Prize winning tent; 1997 was added in January took just under ten Gregoriev; Gerard Young; Rosemary Clark. -

A Brief History of Nuclear Astrophysics

A BRIEF HISTORY OF NUCLEAR ASTROPHYSICS PART I THE ENERGY OF THE SUN AND STARS Nikos Prantzos Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris Stellar Origin of Energy the Elements Nuclear Astrophysics Astronomy Nuclear Physics Thermodynamics: the energy of the Sun and the age of the Earth 1847 : Robert Julius von Mayer Sun heated by fall of meteors 1854 : Hermann von Helmholtz Gravitational energy of Kant’s contracting protosolar nebula of gas and dust turns into kinetic energy Timescale ~ EGrav/LSun ~ 30 My 1850s : William Thompson (Lord Kelvin) Sun heated at formation from meteorite fall, now « an incadescent liquid mass » cooling Age 10 – 100 My 1859: Charles Darwin Origin of species : Rate of erosion of the Weald valley is 1 inch/century or 22 miles wild (X 1100 feet high) in 300 My Such large Earth ages also required by geologists, like Charles Lyell A gaseous, contracting and heating Sun 푀⊙ Mean solar density : ~1.35 g/cc Sun liquid Incompressible = 4 3 푅 3 ⊙ 1870s: J. Homer Lane ; 1880s :August Ritter : Sun gaseous Compressible As it shrinks, it releases gravitational energy AND it gets hotter Earth Mayer – Kelvin - Helmholtz Helmholtz - Ritter A gaseous, contracting and heating Sun 푀⊙ Mean solar density : ~1.35 g/cc Sun liquid Incompressible = 4 3 푅 3 ⊙ 1870s: J. Homer Lane ; 1880s :August Ritter : Sun gaseous Compressible As it shrinks, it releases gravitational energy AND it gets hotter Earth Mayer – Kelvin - Helmholtz Helmholtz - Ritter A gaseous, contracting and heating Sun 푀⊙ Mean solar density : ~1.35 g/cc Sun liquid Incompressible = 4 3 푅 3 ⊙ 1870s: J. -

John Meurig Thomas

obituary John Meurig Thomas (1932–2020) Sir John Meurig Thomas, who was one of the leading materials and catalytic scientists of his generation, sadly died in November 2020, aged 87. homas was born in Wales, the son of a enabling him to study one of the most coal miner, and his early life was spent significant conceptual developments in Tin the Gwendraeth Valley in South catalysis over the last decades — single-site Wales; throughout his life he remained catalysis. Thomas was an early explorer in passionately committed to his native developing this new field. His work land, its language and literature. He was focussed on using mesoporous silica both an undergraduate and postgraduate MCM-41 as a support or tether for new student at Swansea University and after single-site catalysts. MCM-41 provided a brief postdoctoral period at the Atomic ordered mesopores that could be tuned Weapons Establishment, Aldermaston, in diameter, thereby adding a degree of he was appointed a Lecturer at Bangor confinement for the single-site catalysts. University and subsequently Professor at Working with Maschmeyer, Sankar and Aberystwyth University. In 1978 he Credit: Kevin Quinlan / University of Delaware Rey, a landmark publication appeared in moved to the University of Cambridge 19957 in which metallocenes were grafted as Professor of Physical Chemistry and onto the walls of MCM-41 and were shown subsequently to London, where he was measurements of both long-range and to be a highly effective epoxidation catalyst Director of the Royal Institution from local structure on the same sample under for cyclohexene and pinene 1986–1991 — an ideal role for him as it identical reaction conditions. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Crystal Vision Dorothy Hodgkin & the Nobel Prize “Few Were Her Equal in Generosity of Spirit, Breadth of Mind, Cultivated Humaneness, Or Gift for Giving

Crystal Vision Dorothy Hodgkin & the Nobel Prize “Few were her equal in generosity of spirit, breadth of mind, cultivated humaneness, or gift for giving. She should be remembered not only for a lifetime’s succession of brilliantly achieved structures. While those who knew her, experienced her quiet and modest and extremely powerful influence, learned from her more than the positioning of atoms in the three-dimensional molecule, she will be remembered not only with respect, and reverence, and gratitude, but more than anything else, with love. Let that be her lasting memorial.” Anne Sayre, in the Autumn 1995 Newsletter of the American Crystallographic Association Cover image © Emilio Segre Visual Archives/American Institute of Physics/Science Photo Library Letter from the Principal Dr Alice Prochaska, Somerville College Many remarkable woman scientists have passed through Somerville, but few rival Dorothy Hodgkin, whose path-breaking work in crystallography showed a mind not only attuned to high science but one also able to envision a crystal structure from the pattern made by its X-ray diffraction. Her ability to ‘see’ molecules such as cholesterol, penicillin, vitamin B and insulin transformed her field. 2014 sees the fiftieth anniversary of Professor Hodgkin’s Nobel prize. It is also the International Year of Crystallography, marking the 100th anniversary of Max von Laue’s Nobel Prize for Physics, awarded for his discovery that X-rays could be diffracted by crystals. That discovery underpinned Dorothy Hodgkin’s work. We are proud that Somerville supported her at a time when there was widespread opposition to married women pursuing academic careers.