06 Greenwood Press Proof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

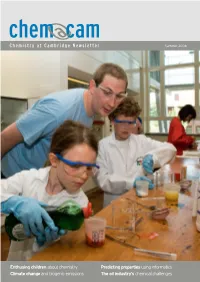

Enthusing Children About Chemistry Climate Change and Biogenic Emissions Predicting Properties Using Informatics the Oil Industr

Summer 2008 Enthusing children about chemistry Predicting properties using informatics Climate change and biogenic emissions The oil industry’s chemical challenges As I see it... So are you finding it increasingly diffi - Oil exploration doesn’t just offer a career for engineers – cult to attract good chemists? chemists are vital, too. Sarah Houlton spoke to Schlumberger’s It can be a challenge, yes. Many of the com - pany’s chemists are recruited here, and they Tim Jones about the crucial role of chemistry in the industry often move on to other sites such as Houston or Paris, but finding them in the first place can be a challenge. Maybe one reason is that the oil People don’t think of Schlumberger as We can’t rely on being able to find suitable industry doesn’t have the greatest profile in a chemistry-using company, but an chemistries in other industries, either, mainly chemistry, and people think it employs engi - engineering one. How important is because of the high temperatures and pressures neers, not chemists. But it’s something the chemistry in oil exploration? that we have to be able to work at. Typically, the upstream oil industry cannot manage without, It’s essential! There are many challenges for upper temperature norm is now 175°C, but even if they don’t realise it! For me, maintaining chemistry in helping to maintain or increase oil we’re increasingly looking to go over 200°C. – if not enhancing – our recruitment is perhaps production. It’s going to become increasingly For heavy oil, where we heat the oil up with one of the biggest issues we face. -

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY Theo James presenting a bouquet to HM The Queen on the occasion of her bicentenary visit, 7 December 1999. by Frank A.J.L. James The Director, Susan Greenfield, looks on Front page: Façade of the Royal Institution added in 1837. Watercolour by T.H. Shepherd or more than two hundred years the Royal Institution of Great The Royal Institution was founded at a meeting on 7 March 1799 at FBritain has been at the centre of scientific research and the the Soho Square house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph popularisation of science in this country. Within its walls some of the Banks (1743-1820). A list of fifty-eight names was read of gentlemen major scientific discoveries of the last two centuries have been made. who had agreed to contribute fifty guineas each to be a Proprietor of Chemists and physicists - such as Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday, a new John Tyndall, James Dewar, Lord Rayleigh, William Henry Bragg, INSTITUTION FOR DIFFUSING THE KNOWLEDGE, AND FACILITATING Henry Dale, Eric Rideal, William Lawrence Bragg and George Porter THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION, OF USEFUL MECHANICAL - carried out much of their major research here. The technological INVENTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS; AND FOR TEACHING, BY COURSES applications of some of this research has transformed the way we OF PHILOSOPHICAL LECTURES AND EXPERIMENTS, THE APPLICATION live. Furthermore, most of these scientists were first rate OF SCIENCE TO THE COMMON PURPOSES OF LIFE. communicators who were able to inspire their audiences with an appreciation of science. -

Historical Group

Historical Group NEWSLETTER and SUMMARY OF PAPERS No. 67 Winter 2015 Registered Charity No. 207890 COMMITTEE Chairman: Dr J A Hudson ! Dr C Ceci (RSC) Graythwaite, Loweswater, Cockermouth, ! Dr N G Coley (Open University) Cumbria, CA13 0SU ! Dr C J Cooksey (Watford, Hertfordshire) [e-mail [email protected]] ! Prof A T Dronsfield (Swanwick, Secretary: Prof. J. W. Nicholson ! Derbyshire) 52 Buckingham Road, Hampton, Middlesex, ! Prof E Homburg (University of TW12 3JG [e-mail: [email protected]] ! Maastricht) Membership Prof W P Griffith ! Prof F James (Royal Institution) Secretary: Department of Chemistry, Imperial College, ! Dr M Jewess (Harwell, Oxon) London, SW7 2AZ [e-mail [email protected]] ! Dr D Leaback (Biolink Technology) Treasurer: Dr P J T Morris ! Mr P N Reed (Steensbridge, Science Museum, Exhibition Road, South ! Herefordshire) Kensington, London, SW7 2DD ! Dr V Quirke (Oxford Brookes University) [e-mail: [email protected]] !Prof. H. Rzepa (Imperial College) Newsletter Dr A Simmons !Dr A Sella (University College) Editor Epsom Lodge, La Grande Route de St Jean, St John, Jersey, JE3 4FL [e-mail [email protected]] Newsletter Dr G P Moss Production: School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS [e-mail [email protected]] http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/rschg/ http://www.rsc.org/membership/networking/interestgroups/historical/index.asp 1 RSC Historical Group Newsletter No. 67 Winter 2015 Contents From the Editor 2 ROYAL SOCIETY OF CHEMISTRY HISTORICAL GROUP NEWS The Life and Work of Sir John Cornforth CBE AC FRS 3 Royal Society of Chemistry News 4 Feedback from the Summer 2014 Newsletter – Alwyn Davies 4 Another Object to Identify – John Nicholson 4 Published Histories of Chemistry Departments in Britain and Ireland – Bill Griffith 5 SOCIETY NEWS News from the Historical Division of the German Chemical Society – W.H. -

RSC/SCI Joint Colloids Group Newsletter – Summer 2015

RSC/SCI Joint Colloids Group Newsletter – Summer 2015 Contents: Editors Introduction: In this newsletter, you will find a description of the very recent event organised alongside the award of Chair’s welcome 2 the Rideal medal to Prof. Paul Luckham. There is also a particularly interesting interview of Paul Rideal medal 3 highlighting some specific areas of his career to date. Other events recently organised and hosted by the committee are reported on. We also Reports on conferences 5 announce here upcoming UK meetings of interest. Upcoming meetings 8 A particular request is made at the end of the newsletter for active members of the colloid Your committee needs you 9 community in UK to get involved with the events we organise and with the committee activities in general. We would particularly appreciate enquiries from younger members of the community, including students. Claire Pizzey and Olivier Cayre 1 CHAIR’S WELCOME Welcome to the Joint Colloid Group Cambridge. We then have an award meeting for the 2014 and 2015 McBain Medal Winners Summer 2015 newsletter. Professor Rachel O’Reilly (University of Warwick) and Professor Giuseppe Battaglia (University College London) on 8th December 2015 at SCI in 2015 has already been a busy year for the Joint London. Planning has also started for the 2017 UK Colloids Group. We have already organised two Colloid Multi-day meeting. This is our flagship meetings this year: Arrested Gels: Dynamics, event and I am keen for us to build on the success Structure and Applications in March, in Cambridge of the first two meetings. -

Instituto De Química Física Rocasolano Del Consejo Superior De Investigaciones Científi Cas

Física y Química en la Colina de los Chopos Instituto de Química Física Rocasolano del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científi cas Física y Química en la Colina de los Chopos Instituto de Química Física Rocasolano del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científi cas Editores Carlos González Ibáñez Antonio Santamaría García CONSEJO SUPERIOR DE INVESTIGACIONES CIENTÍFICAS MADRID 2008 Física y Química en la Colina de los Chopos Instituto de Química Física Rocasolano del Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas Editores: CARLOS GONZÁLEZ IBÁÑEZ Investigador científico y vicedirector del Instituto de Química-Física Rocasolano del CSIC ANTONIO SANTAMARÍA GARCÍA Científico titular de la Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos y Área de Cultura Científica del CSIC Reservados todos los derechos por la legislación en materia de Propiedad Intelectual. Ni la totalidad ni parte de este libro, in- cluido el diseño de la cubierta, puede reproducirse, almacenarse o transmitirse en manera alguna por ningún medio ya sea elec- trónico, químico, mecánico, óptico, informático, de grabación o de fotocopia, sin permiso previo por escrito de la editorial. Las noticias, asertos y opiniones contenidos en esta obra son de la exclusiva responsabilidad del autor o autores. La editorial, por su parte, sólo se hace responsable del interés científico de sus publicaciones. Fotografía de cubierta: Base 12 © De cada texto: su autor. © De la presente edición: CSIC. ISBN: 00-00000-000-0 NIPO: 00-00000-000-0 Depósito legal: M-00.000-2008 Diseño y maquetación: Closas-Orcoyen, -

Chem@Cam 51.Pdf

Spring 2015 Synthetic polymers with DNA properties Automated synthesis : joining the dots Wood preservation on the Mary Rose The impact of atmospheric chemistry As I see it... How did your education lead to your job as a journalist? Cambridge chemistry (and Chem@Cam) alumnus Phillip Broadwith I really enjoyed chemistry at school, and is now business editor at Chemistry World. He explains to Sarah after my A-levels I spent a year in indus - try at GlaxoWellcome (as it then was) in Houlton how he got there, and what makes his job so exciting Ware. I was doing analytical chemistry, testing how new valve designs for chemistry community, at least at a asthma inhalers affect how the drug superficial level. Sometimes we spot inside is delivered. During my degree I connections between scientific fields was geared up to work in pharma – I that seem disparate, and it’s the same on went back to the same lab the summer the business side – you get a view of after my first year, then had a synthetic what’s going on in the tumultuously placement at GSK in Harlow after my changing landscape, and can pick out second, and another summer doing trends. Being in the middle gives us the synthesis with AstraZeneca at Alderley opportunity to see things as they are Park after my third year. happening, and draw them together. I stayed on in Cambridge for a total Our new editor is keen that we should synthesis PhD with Jon Burton – he was become more involved in the chemical fantastic to work with and was doing sciences community, and use that top- interesting chemistry. -

Remembering the First World War 1 Remembering the First World War

Remembering the First World War 1 Remembering the First World War Contents 3 Introduction 4 The Chemical Society Memorial 26 The Institute of Chemistry Memorial 42 The Men Who Came Home 53 The Role of Women Chemists 2 Introduction In his speech at the Anniversary Dinner of 3 the Chemical Society on Friday 14 March 1913, invited guest H. G. Wells spoke of the public perception of chemistry and his personal awe at what science had the potential to achieve. In the majestic rooms of the Hotel Metropole in London, the renowned novelist spoke of how he had always tried to make the scientific man, the hero. Believing that science was the ‘true romance’ more than the traditional tales of knights rescuing damsels in distress, he felt that the small band of working chemists were rapidly changing the conditions of human life. Wells spoke of his belief that while chemists had not made war impossible, they had made it preposterous; as most of Europe had been arming itself with weapons that chemists had been putting into their hands, they had come to realise that these weapons had the potential to destroy everything; the cost of war would far outweigh any benefit. Preposterous or not, war was declared the following year and among the attendees of the 1913 dinner was 23 year old Eric Rideal. Three years’ later, he saw first-hand, the chaos and destruction wrought by war as he worked to supply water to troops on the Somme. Hundreds more members of the Chemical Society and the Institute of Chemistry fought for their country between 1914 and 1918; 82 of those that had died were subsequently commemorated on the First World War memorials that now hang in the premises of the Royal Society of Chemistry in London. -

The Development of Catalysis

Trim Size: 6.125in x 9.25in Single Columnk Zecchina ffirs.tex V2 - 02/20/2017 1:50pm Page i The Development of Catalysis k k k Trim Size: 6.125in x 9.25in Single Columnk Zecchina ffirs.tex V2 - 02/20/2017 1:50pm Page iii The Development of Catalysis A History of Key Processes and Personas in Catalytic Science and Technology Adriano Zecchina Salvatore Califano k k k Trim Size: 6.125in x 9.25in Single Columnk Zecchina ffirs.tex V2 - 02/20/2017 1:50pm Page iv Copyright © 2017 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 750-4470, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions. Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. -

*Accepted Manuscript***********

www.technology.matthey.com Johnson Matthey’s international journal of research exploring science and technology in industrial applications ************Accepted Manuscript*********** This article is an accepted manuscript It has been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but has not yet been copyedited, house styled, proofread or typeset. The fi nal published version may contain differences as a result of the above procedures It will be published in the July 2018 issue of the Johnson Matthey Technology Review Please visit the website http://www.technology.matthey.com/ for Open Access to the article and the full issue once published Editorial team Manager Dan Carter Editor Sara Coles Senior Information Offi cer Elisabeth Riley Johnson Matthey Technology Review Johnson Matthey Plc Orchard Road Royston SG8 5HE UK Tel +44 (0)1763 253 000 Email [email protected] Foettinger_06a_SC ACCEPTED MANUSCRIPT 11/04/2018 < https://doi.org/10.1595/205651318X15234323420569> <First page number: TBC> In situ and Operando Spectroscopy: A Powerful Approach Towards Understanding of Catalysts Liliana Lukashuk1 Institute of Materials Chemistry, Technische Universität Wien, Getreidemarkt 9/BC/01, 1060 Vienna, Austria 1Current address: Johnson Matthey Technology Centre, PO Box 1, Belasis Avenue, Billingham, Cleveland, TS23 1LB, UK Karin Foettinger* Institute of Materials Chemistry, Technische Universität Wien, Getreidemarkt 9/BC/01, 1060 Vienna, Austria *Email: <[email protected]> <ABSTRACT> The improvement of catalytic processes is strongly related to the better performance of catalysts (i.e., higher conversion, selectivity, yield, and stability). Additionally, the desired catalysts should meet the requirements of being “low cost” as well as “environmentally and user-friendly”. All these requirements can only be met by catalyst development and optimization following new approaches in design and synthesis. -

Assembling Life

ASSEMBLING LIFE. Models, the cell, and the reformations of biological science, 1920-1960 Max Stadler Centre for the History of Science, Technology and Medicine Imperial College, London University of London PhD dissertation 1 I certify that all the intellectual contents of this thesis are of my own, unless otherwise stated. London, October 2009 Max Stadler 2 Acknowledgments My thanks to: my friends and family; esp. my mother and Julia who didn't mind their son and brother becoming a not-so-useful member of society, helped me survive in the real world, and cheered me up when things ; my supervisor, Andrew Mendelsohn, for many hours of helping me sort out my thoughts and infinite levels of enthusiasm (and Germanisms-tolerance); my second supervisor, David Edgerton, for being the intellectual influence (I thought) he was; David Munns, despite his bad musical taste and humour, as a brother-in-arms against disciplines; Alex Oikonomou, for being a committed smoker; special thanks (I 'surmise') to Hermione Giffard, for making my out-of-the-suitcase life much easier, for opening my eyes in matters of Frank Whittle and machine tools, and for bothering to proof-read parts of this thesis; and thanks to all the rest of CHoSTM; thanks also, for taking time to read and respond to over-length drafts and chapters: Cornelius Borck; Stephen Casper; Michael Hagner; Rhodrie Hayward; Henning Schmidgen; Fabio de Sio; Sktili Sigurdsson; Pedro Ruiz Castell; Andrew Warwick; Abigail Woods; to Anne Harrington for having me at the History of Science Department, Harvard, and to Hans- Joerg Rheinberger for having me at the Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science in Berlin; thanks, finally, to all those who in some way or another encouraged, accompanied and/or enabled the creation and completion of this thing, especially: whoever invented the internet; Hanna Rose Shell; and the Hans Rausing Fund. -

The Faraday Society and the Birth of Polymer Science

SpringerBriefs in Molecular Science History of Chemistry Series Editor Seth C. Rasmussen, Fargo, USA For further volumes: http://www.springer.com/series/10127 Jacobus Henricus Van’t Hoff (1852–1911, Nobel 1901) Grandfather of Polymer Science Edgar Fahs Smith Collection, University of Pennsylvania Libraries Gary Patterson A Prehistory of Polymer Science 123 Gary Patterson Department of Chemistry Carnegie Mellon University 4400 Fifth Avenue Pittsburgh, PA 15213 USA e-mail: [email protected] ISSN 2191-5407 e-ISSN 2191-5415 ISBN 978-3-642-21636-7 e-ISBN 978-3-642-21637-4 DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-21637-4 Springer Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York Library of Congress Control Number: 2011940054 Ó The Author(s) 2012 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broad- casting, reproduction on microfilm or in any other way, and storage in data banks. Duplication of this publication or parts thereof is permitted only under the provisions of the German Copyright Law of September 9, 1965, in its current version, and permission for use must always be obtained from Springer. Violations are liable to prosecution under the German Copyright Law. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. Printed on acid-free paper Springer is part of Springer Science+Business Media (www.springer.com) Preface The present volume examines the time period before there was a coherent sci- entific community devoted to the study of macromolecules. -

The RSC and SCI Joint Colloids Group's Three Awards: the Legacies of Graham, Mcbain and Rideal

The RSC and SCI Joint Colloids Group’s Three Awards: the Legacies of Graham, McBain and Rideal Brian Vincent School of Chemistry, University of Bristol, BS8 1TS, UK [email protected] Introduction Thomas Graham William McBain Sir Eric Rideal (1805-1869) (1882-1953) (1890-1974) The UK Joint Colloids Group (JCG) is a joint working group of the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Colloid and Interface Science Group and the Society of Chemical Industry’s Colloid and Surface Chemistry Group. The JCG committee administers three joint RSC/SCI awards. These awards recognise and honour current outstanding researchers in the subject, at varying stages of their careers: the Thomas Graham Lecture for persons in mid-career, the McBain Medal for early-stage researchers and the Sir Eric Rideal Award and Lecture for life- time achievement. Thomas Graham, James William McBain and Sir Eric Rideal are three of the “big names” in the history of colloid and interface science in the UK. They were the leading lights in the establishment of three pioneering academic centres of research in this subject: University College London (UCL), Bristol University and Cambridge University, respectively. The purpose of this article is to discuss the contributions to colloid and interface science made by Graham, McBain and Rideal, at their respective institutions, and to describe briefly how research in this field continued at each of these major centres in their wake. Thomas Graham and University College London Thomas Graham was born in Glasgow in 1805 and educated at Glasgow High School. He enrolled at the University of Glasgow in 1819, to study chemistry, receiving his MA in 1824.