The RSC and SCI Joint Colloids Group's Three Awards: the Legacies of Graham, Mcbain and Rideal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary Journal Item How to cite: Stenhouse, Brigitte (2020). Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary. The Mathematical Intelligencer (Early Access). For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2020 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1007/s00283-020-09998-6 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Mister Mary Somerville: Husband and Secretary BRIGITTE STENHOUSE ary Somerville’s life as a mathematician and mathematician). Although no scientific learned society had a savant in nineteenth-century Great Britain was formal statute barring women during Somerville’s lifetime, MM heavily influenced by her gender; as a woman, there was nonetheless a great reluctance even toallow women her access to the ideas and resources developed and into the buildings, never mind to endow them with the rights circulated in universities and scientific societies was highly of members. Except for the visit of the prolific author Margaret restricted. However, her engagement with learned institu- Cavendish in 1667, the Royal Society of London did not invite tions was by no means nonexistent, and although she was women into their hallowed halls until 1876, with the com- 90 before being elected a full member of any society mencement of their second conversazione [15, 163], which (Societa` Geografica Italiana, 1870), Somerville (Figure 1) women were permitted to attend.1 As late as 1886, on the nevertheless benefited from the resources and social nomination of Isis Pogson as a fellow, the Council of the Royal networks cultivated by such institutions from as early as Astronomical Society chose to interpret their constitution as 1812. -

The European Physical Journal E Soft Matter

Announcing a new section of The European Physical Journal E Soft Matter ‘Soft matter’ is a generic term that has come to refer to a large group of condensed systems including polymers, supramolecular assemblies of purpose-designed organic molecules, liquid crystals, colloids, lyotropic systems, emulsions, biopolymers, and biomembranes. These are systems – often complex fluids – that display a strong response to weak external perturba- tions and also share many other common properties. Their similarities have led to the grad- ual emergence of the research field of soft matter sciences. Soft matter sciences include the 123 study of structured and surface-dominated materials such as microemulsions, block-copoly- mer mesophases, foams, and granular matter, whose properties are governed by slow internal dynamics and sensitivity to extremely weak external perturbations. Other characteristic features of these systems include entropic forces and colloidal or mesoscopic length scales, whose investigation demands new experimental techniques such as micromanipulation. The study of soft condensed matter has already stimulated fruitful interactions between physicists, chemists, and engineers, and is now reaching out to biologists. Most importantly, complex fluids have many applications in every- day life, and fundamental research on soft matter is often closely linked to industrial research. A broad interdiscipli- nary community encompassing all these areas of science has emerged over the last thirty years, and with it our knowledge of soft matter has grown considerably. A great many European scientists now believe that a journal dedicated to all aspects of soft matter science is urgently needed. The new section, EPJ E – Soft Matter, of The European Physical Journal aims to fill this need. -

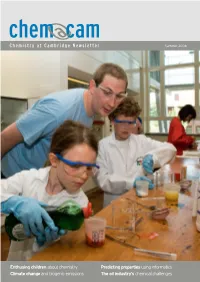

Enthusing Children About Chemistry Climate Change and Biogenic Emissions Predicting Properties Using Informatics the Oil Industr

Summer 2008 Enthusing children about chemistry Predicting properties using informatics Climate change and biogenic emissions The oil industry’s chemical challenges As I see it... So are you finding it increasingly diffi - Oil exploration doesn’t just offer a career for engineers – cult to attract good chemists? chemists are vital, too. Sarah Houlton spoke to Schlumberger’s It can be a challenge, yes. Many of the com - pany’s chemists are recruited here, and they Tim Jones about the crucial role of chemistry in the industry often move on to other sites such as Houston or Paris, but finding them in the first place can be a challenge. Maybe one reason is that the oil People don’t think of Schlumberger as We can’t rely on being able to find suitable industry doesn’t have the greatest profile in a chemistry-using company, but an chemistries in other industries, either, mainly chemistry, and people think it employs engi - engineering one. How important is because of the high temperatures and pressures neers, not chemists. But it’s something the chemistry in oil exploration? that we have to be able to work at. Typically, the upstream oil industry cannot manage without, It’s essential! There are many challenges for upper temperature norm is now 175°C, but even if they don’t realise it! For me, maintaining chemistry in helping to maintain or increase oil we’re increasingly looking to go over 200°C. – if not enhancing – our recruitment is perhaps production. It’s going to become increasingly For heavy oil, where we heat the oil up with one of the biggest issues we face. -

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

Further Reading: Michael Faraday

Further Reading: Michael Faraday General reading Geoffrey Cantor, Michael Faraday: Sandemanian and Scientist. A Study of Science and Religion in the Nineteenth Century, (London, 1991). David Gooding, Experiment and the Making of Meaning: Human Agency in Scientific Observation and Experiment, (Dordrecht, 1991). David Gooding and Frank A.J.L. James (eds.), Faraday Rediscovered: Essays on the Life and Work of Michael Faraday, 1791‐1867, (London, 1985). Frank A.J.L. James (ed.), ‘The Common Purposes of Life’: Science and society at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, (Aldershot, 2002). Frank A.J.L. James, Michael Faraday: A very short Introduction. (Oxford, 2010) Alan E. Jeffreys, Michael Faraday: A List of His Lectures and Published Writings, (London, 1960). Published books by Faraday, mainly collections of papers and lecture notes, some published after his death: Chemical Manipulation, Being Instructions to Students in Chemistry. (1827). Experimental Researches in Electricity, Vol I, II& III (1837, 1844, 1855) Experimental Researches in Chemistry and Physics (1859). W. Crookes. ed. A Course of six lectures on the Various Forces of Matter (1860) W. Crookes. ed. A Course of six lectures on the Chemical History of a Candle, (1861) W. Crookes. ed. On the Various Forces in Nature. (1873) The liquefaction of gases (1896.) Published texts by Faraday The vast majority of Faraday’s manuscripts, apart from letters, have been published on microfilm and cd. Frank A.J.L. James, Guide to the Microfilm edition of the Manuscripts of Michael Faraday (1791‐1867) from the Collections of the Royal Institution, The Institution of Electrical Engineers, The Guildhall Library [and] The Royal Society, (2nd ed., Wakefield, 2001). -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

The Scottish Genealogist

THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGY SOCIETY THE SCOTTISH GENEALOGIST INDEX TO VOLUMES LIX-LXI 2012-2014 Published by The Scottish Genealogy Society The Index covers the years 2012-2014 Volumes LIX-LXI Compiled by D.R. Torrance 2015 The Scottish Genealogy Society – ISSN 0330 337X Contents Please click on the subject to be visited. ADDITIONS TO THE LIBRARY APPRECIATIONS ARTICLE TITLES BOOKMARKS BOOK REVIEWS CONTRIBUTORS FAMILY TREES GENERAL INDEX ILLUSTRATIONS INTRODUCTION QUERIES INTRODUCTION Where a personal or place name is mentioned several times in an article, only the first mention is indexed. LIX, LX, LXI = Volume number i. ii. iii. iv = Part number 1- = page number ; - separates part numbers within the same volume : - separates volume numbers BOOKMARKS The contents of this CD have been bookmarked. Select the second icon down at the left-hand side of the document. Use the + to expand a section and the – to reduce the selection. If this icon is not visible go to View > Show/Hide > Navigation Panes > Bookmarks. Recent Additions to the Library (compiled by Joan Keen & Eileen Elder) LIX.i.43; ii.102; iii.154: LX.i.48; ii.97; iii.144; iv.188: LXI.i.33; ii.77; iii.114; Appreciations 2012-2014 Ainslie, Fred LIX.i.46 Ferguson, Joan Primrose Scott LX.iv.173 Hampton, Nettie LIX.ii.67 Willsher, Betty LIX.iv.205 Article Titles 2012-2014 A Call to Clan Shaw LIX.iii.145; iv.188 A Case of Adultery in Roslin Parish, Midlothian LXI.iv.127 A Knight in Newhaven: Sir Alexander Morrison (1799-1866) LXI.i.3 A New online Medical Database (Royal College of Physicians) -

06 Greenwood Press Proof

Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 57 (1), 85–105 (2003) doi 10.1098/rsnr.2003.0197 AN ANTIPODEAN LABORATORY OF REMARKABLE DISTINCTION by NORMAN N. GREENWOOD1 FRS AND JOHN A. SPINK2 1Department of Chemistry, The University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, UK 2Department of History and Philosophy of Science, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, 3010, Australia SUMMARY In an astonishingly short period in September 1939, while on a brief visit from England, F.P. Bowden (FRS 1948) conceived the need, and obtained the approval of the Australian Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), to establish a wartime friction and bearings research laboratory within the University of Melbourne. He recruited a galaxy of young talent, which during the following six years made major contributions to four very diverse defence-related problems. The infant laboratory survived the peace and eventually evolved into the internationally admired Division of Tribophysics. Many of the original members of the group went on to distinguished careers in Australia, the UK and elsewhere. The story of the exciting early days of the laboratory and the subsequent achievements of its staff are briefly described. INTRODUCTION The year 2003 marks the centenary of the birth of F.P. Bowden FRS (figure 1). In September 1939, at the outbreak of World War II, Philip Bowden was on a brief family visit to Australia. He had been born in Hobart, Tasmania, in 1903 and obtained his BSc and MSc from the University of Tasmania.1 He then went to Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, as an Exhibition of 1851 Overseas Research Scholar to study for his PhD under Dr Eric Rideal (later Sir Eric Rideal FRS). -

Herschel, Humboldt and Imperial Science

CHAPTER 41 Herschel, Humboldt and Imperial Science Christopher Carter In science, the nineteenth century is known as the beginning of a systematic approach to geophysics, an age when terrestrial magnetism, meteorology and other worldwide phenomena were studied for the first time on a large scale. International efforts to study the earth’s climate, tides and magnetic field became common in the first half of this century, in large part because of the impetus given to the field by the work of Alexander von Humboldt. Due to Humboldt’s influence, a system of geomagnetic observatories soon covered most of the European continent.1 But one prominent nation remained outside of this system of observations. Despite Britain’s inherent interest in geomag- netic studies (due to its maritime concerns) the laissez-faire attitudes of the British political system weakened efforts to subsidize state funded scientific projects. Not until the 1830s did Britain join with other European nations in the geophysical arena. This cooperation was beneficial to the science, as it brought not only Britain’s considerable scientific resources to bear on the problem, but it also opened up Britain’s imperial holdings as new stations to expand the observational system. Humboldt’s 1836 letter to the Duke of Sussex (President of the Royal Society), suggesting the establishment of geomagnetic observatories in Brit- ish colonies, provides an initial point of reference for our investigations.2 However, while welcomed by the scientific community, Humboldt’s appeal 1. By 1835, continental geomagnetic stations were operating at Altona, Augsburg, Berlin, Breda, Breslau, Copenhagen, Freiburg, Goettingen, Hanover, Leipzig, Marburg, Milan, Munich, St. -

Charles Kemball Was One of the Most Distinguished British Chemists of His Generation

CHARLES KEMBALL CBE, MA, ScD(Cantab), DSc(H-W,QUB), C Chem, FRSC, MRIA, FRS Charles Kemball was one of the most distinguished British chemists of his generation. He was born in Edinburgh in 1923, the only son of a distinguished dental surgeon, Charles Henry Kemball FRSE , and was educated at Edinburgh Academy. It was clear from an early age that he was very talented and even in the preparatory school at Edinburgh Academy his teacher found his speed at mental arithmetic rather disconcerting. Bright pupils were encouraged towards the Classics and it was only after the School Certificate Examination that a perceptive teacher persuaded him to move to the Sciences. He had an aptitude at shooting and was a member of the shooting VIII which won the Kinder Cup at Bisley in 1939. Subsequently he was captain of shooting and won the shooting cup in his final two years at the Academy. Despite his late move to sciences he won an Entrance Exhibition in Natural Sciences and went up to Trinity College Cambridge in 1940. At this time his interests lay more with Mathematics and Physics but he later moved to Chemistry and gained First Class Honours in Parts I and II of the Tripos. He went on to do research in the Department of Colloid Science under the direction of Professor E K Rideal, financed by a grant from the Ministry of Aircraft Production, to investigate problems in adhesion. In addition to some direct investigations into the strength of various adhesives for metals, the main work undertaken was a detailed study of the adsorption of vapours on the surface of mercury, to determine the magnitude of the forces attracting the molecules to the metal. -

Active Soft Matter

View Article Online / Journal Homepage / Table of Contents for this issue Soft Matter Dynamic Article LinksC< Cite this: Soft Matter, 2011, 7, 3050 www.rsc.org/softmatter EDITORIAL Active soft matter DOI: 10.1039/c1sm90014e Nature provides us with many examples appear in this themed issue. Within it, particular viscoelastic properties, by of complex materials, ranging from rela- various aspects and manifestations of enzymatic activity. In this issue, the tively passive, near equilibrium structures activity are explored in biological or bio- effects of activity on viscoelasticity are such as wood and bone to highly active, logically inspired systems. These range explored in systems ranging from highly far from equilibrium systems such as from the nanometre or single-molecule simplified in vitro constructs to living cells migrating cells. Living cells are kept out of level to the near macroscopic level of and even tissues. In addition to mechan- equilibrium in large part by metabolic collective behavior, and represent many ical and viscoelastic effects, local motor processes and energy-consuming enzymes different avenues and approaches to the activity also leads to non-thermal fluctu- such as molecular motors that generate study of active soft matter. ations,9,10 which are also studied in this forces and drive the machinery behind cell Activity can manifest itself in dynamic issue. locomotion and many other cellular patterns, such as vortices or asters, in At a more discrete level, the motion of processes; molecular motors are also the which stiff filaments radiate out from individual active particles, or modest basis of muscle contraction at the a common center,4 in analogy with the numbers of these, continues to surprise. -

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY Theo James presenting a bouquet to HM The Queen on the occasion of her bicentenary visit, 7 December 1999. by Frank A.J.L. James The Director, Susan Greenfield, looks on Front page: Façade of the Royal Institution added in 1837. Watercolour by T.H. Shepherd or more than two hundred years the Royal Institution of Great The Royal Institution was founded at a meeting on 7 March 1799 at FBritain has been at the centre of scientific research and the the Soho Square house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph popularisation of science in this country. Within its walls some of the Banks (1743-1820). A list of fifty-eight names was read of gentlemen major scientific discoveries of the last two centuries have been made. who had agreed to contribute fifty guineas each to be a Proprietor of Chemists and physicists - such as Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday, a new John Tyndall, James Dewar, Lord Rayleigh, William Henry Bragg, INSTITUTION FOR DIFFUSING THE KNOWLEDGE, AND FACILITATING Henry Dale, Eric Rideal, William Lawrence Bragg and George Porter THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION, OF USEFUL MECHANICAL - carried out much of their major research here. The technological INVENTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS; AND FOR TEACHING, BY COURSES applications of some of this research has transformed the way we OF PHILOSOPHICAL LECTURES AND EXPERIMENTS, THE APPLICATION live. Furthermore, most of these scientists were first rate OF SCIENCE TO THE COMMON PURPOSES OF LIFE. communicators who were able to inspire their audiences with an appreciation of science.