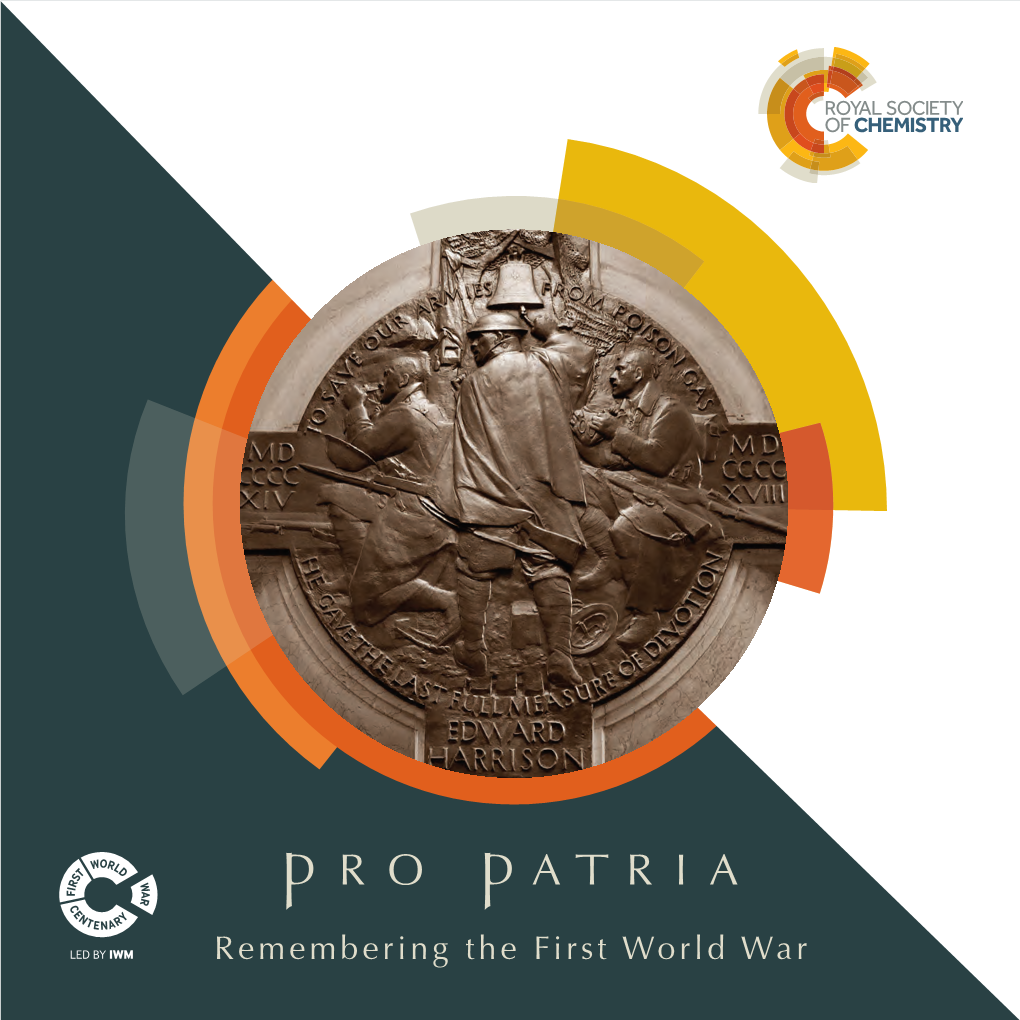

Remembering the First World War 1 Remembering the First World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater London Authority

Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London March 2009 Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London A report by Experian for the Greater London Authority March 2009 copyright Greater London Authority March 2009 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978 1 84781 227 8 This publication is printed on recycled paper Experian - Business Strategies Cardinal Place 6th Floor 80 Victoria Street London SW1E 5JL T: +44 (0) 207 746 8255 F: +44 (0) 207 746 8277 This project was funded by the Greater London Authority and the London Development Agency. The views expressed in this report are those of Experian Business Strategies and do not necessarily represent those of the Greater London Authority or the London Development Agency. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................... 5 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 5 CONSUMER EXPENDITURE PROJECTIONS .................................................................................... 6 CURRENT COMPARISON FLOORSPACE PROVISION ....................................................................... 9 RETAIL CENTRE TURNOVER........................................................................................................ 9 COMPARISON GOODS FLOORSPACE REQUIREMENTS -

World War I Casualty Biographies

St Martins-Milford World War I Casualty Biographies This memorial plaque to WW1 is in St Martin’s Church, Milford. There over a 100 listed names due to the fact that St Martin’s church had one of the largest congregations at that time. The names have been listed as they are on the memorial but some of the dates on the memorial are not correct. Sapper Edward John Ezard B Coy, Signal Corps, Royal Engineers- Son of Mr. and Mrs. J Ezard of Manchester- Husband of Priscilla Ezard, 32, Newton Cottages, The Friary, Salisbury- Father of 1 and 5 year old- Born in Lancashire in 1883- Died in hospital 24th August 1914 after being crushed by a lorry. Buried in Bavay Communal Cemetery, France (12 graves) South Part. Private George Hawkins 1st Battalion Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry- Son of George and Caroline Hawkins, 21 Trinity Street, Salisbury- Born in 1887 in Shrewton- He was part of the famous Mon’s retreat- His body was never found- Died on 21st October 1914. (818 died on that day). Commemorated on Le Touret Memorial, France. Panel 19. Private Reginald William Liversidge 1st Dorsetshire Regiment- Son of George and Ellen Liversidge of 55, Culver Street, Salisbury- Born in 1892 in Salisbury- He was killed during the La Bassee/Armentieres battles- His body was never found- Died on 22nd October 1914 Commemorated on Le Touret Memorial, France. Panel 22. Corporal Thomas James Gascoigne Shoeing Smith, 70th Battery Royal Field Artillery- Husband of Edith Ellen Gascoigne, 54 Barnard Street, Salisbury- Born in Croydon in 1887-Died on wounds on 30th September 1914. -

The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2Nd December 1917

Centre for First World War Studies A Moonlight Massacre: The Night Operation on the Passchendaele Ridge, 2nd December 1917 by Michael Stephen LoCicero Thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts & Law June 2011 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract The Third Battle of Ypres was officially terminated by Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig with the opening of the Battle of Cambrai on 20 November 1917. Nevertheless, a comparatively unknown set-piece attack – the only large-scale night operation carried out on the Flanders front during the campaign – was launched twelve days later on 2 December. This thesis, a necessary corrective to published campaign narratives of what has become popularly known as „Passchendaele‟, examines the course of events from the mid-November decision to sanction further offensive activity in the vicinity of Passchendaele village to the barren operational outcome that forced British GHQ to halt the attack within ten hours of Zero. A litany of unfortunate decisions and circumstances contributed to the profitless result. -

The First World War Centenary Sale | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 1 October 2014 21999

ALE S ENARY ENARY T WORLD WAR CEN WORLD WAR T Wednesday 1 October 2014 Wednesday Knightsbridge, London THE FIRS THE FIRST WORLD WAR CENTENARY SALE | Knightsbridge, London | Wednesday 1 October 2014 21999 THE FIRST WORLD WAR CENTENARY SALE Wednesday 1 October 2014 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London BONHAMS ENQUIRIES SALE NUMBER IMPORTANT INFORMATION Montpelier Street 21999 The United States Government Knightsbridge Books, Manuscripts, has banned the import of ivory London SW7 1HH Photographs and Ephemera CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing www.bonhams.com Matthew Haley £20 ivory are indicated by the symbol +44 (0)20 7393 3817 Ф printed beside the lot number VIEWING [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder in this catalogue. Sunday 28 September information including after-sale 11am to 3pm Medals collection and shipment. Monday 29 September John Millensted 9am to 4.30pm +44 (0)20 7393 3914 Please see back of catalogue Tuesday 30 September [email protected] for important notice to bidders 9am to 4.30pm Wednesday 1 October Militaria ILLUSTRATIONS 9am to 11am David Williams Front cover: Lot 105 +44 (0)20 7393 3807 Inside front cover: Lot 48 BIDS [email protected] Inside back cover: Lot 128 +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Back cover: Lot 89 +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Pictures and Prints To bid via the internet Thomas Podd please visit www.bonhams.com +44 (0)20 7393 3988 [email protected] New bidders must also provide proof of identity when submitting Collectors bids. Failure to do this may result Lionel Willis in your bids not being processed. -

Hydro-Power and the Promise of Modernity and Development in Ghana: Comparing the Akosombo and Bui Dam Projects

HYDRO-POWER AND THE PROMISE OF MODERNITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN GHANA: COMPARING THE AKOSOMBO AND BUI DAM PROJECTS Stephan F. Miescher, University of California, Santa Barbara & Dzodzi Tsikata, University of Ghana n 2007, as Ghanaians were suffering another electricity crisis with frequent power outages, President J. A. Kufuor celebrated I in a festive mode the sod cutting for the country’s third large hydro-electric dam at Bui across the Black Volta in the Brong Ahafo Region.1 The new 400 megawatt (MW) power project promises to guarantee Ghana’s electricity supply and to develop neglected parts of the north. The Bui Dam had been planned since the 1920s as part of the original Volta River Project: harnessing the river by producing ample electricity for processing the country’s bauxite. In the early 1960s, when President Kwame Nkrumah began to implement the Volta River Project by building the Akosombo Dam, Bui was supposed to follow as part of a grand plan for the industrialization and modernization of Ghana and Africa. Since the 1980s, periodic electricity crises due to irregular rainfall have undermined Ghana’s reliance on Akosombo. By the turn of the century, these crises had created a sense of urgency to realize the Bui project in spite of an increasing international critique of large dams. Although there is more than a forty-year gap between the 1 See press reporting in Daily Mail, 24 August 2007, and the Ghanaian Chroni- cle, 27 August 2007. The sod cutting ceremony, analogous to a grass-cutting or ribbon-cutting event, symbolically marks the beginning of construction for a major infrastructure project. -

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften Des Historischen Kollegs

The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Schriften des Historischen Kollegs Herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching Kolloquien 91 The Purpose of the First World War War Aims and Military Strategies Herausgegeben von Holger Afflerbach An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Schriften des Historischen Kollegs herausgegeben von Andreas Wirsching in Verbindung mit Georg Brun, Peter Funke, Karl-Heinz Hoffmann, Martin Jehne, Susanne Lepsius, Helmut Neuhaus, Frank Rexroth, Martin Schulze Wessel, Willibald Steinmetz und Gerrit Walther Das Historische Kolleg fördert im Bereich der historisch orientierten Wissenschaften Gelehrte, die sich durch herausragende Leistungen in Forschung und Lehre ausgewiesen haben. Es vergibt zu diesem Zweck jährlich bis zu drei Forschungsstipendien und zwei Förderstipendien sowie alle drei Jahre den „Preis des Historischen Kollegs“. Die Forschungsstipendien, deren Verleihung zugleich eine Auszeichnung für die bisherigen Leis- tungen darstellt, sollen den berufenen Wissenschaftlern während eines Kollegjahres die Möglich- keit bieten, frei von anderen Verpflichtungen eine größere Arbeit abzuschließen. Professor Dr. Hol- ger Afflerbach (Leeds/UK) war – zusammen mit Professor Dr. Paul Nolte (Berlin), Dr. Martina Steber (London/UK) und Juniorprofessor Simon Wendt (Frankfurt am Main) – Stipendiat des Historischen Kollegs im Kollegjahr 2012/2013. Den Obliegenheiten der Stipendiaten gemäß hat Holger Afflerbach aus seinem Arbeitsbereich ein Kolloquium zum Thema „Der Sinn des Krieges. Politische Ziele und militärische Instrumente der kriegführenden Parteien von 1914–1918“ vom 21. -

The Western Front the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Westernthe Front

Ed 2 June 2015 2 June Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Western Front The Western Creative Media Design ADR003970 Edition 2 June 2015 The Somme Battlefield: Newfoundland Memorial Park at Beaumont Hamel Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The Somme Battlefield: Lochnagar Crater. It was blown at 0728 hours on 1 July 1916. Mike St. Maur Sheil/FieldsofBattle1418.org The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 1 The Western Front 2nd Edition June 2015 ii | THE WESTERN FRONT OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR ISBN: 978-1-874346-45-6 First published in August 2014 by Creative Media Design, Army Headquarters, Andover. Printed by Earle & Ludlow through Williams Lea Ltd, Norwich. Revised and expanded second edition published in June 2015. Text Copyright © Mungo Melvin, Editor, and the Authors listed in the List of Contributors, 2014 & 2015. Sketch Maps Crown Copyright © UK MOD, 2014 & 2015. Images Copyright © Imperial War Museum (IWM), National Army Museum (NAM), Mike St. Maur Sheil/Fields of Battle 14-18, Barbara Taylor and others so captioned. No part of this publication, except for short quotations, may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the permission of the Editor and SO1 Commemoration, Army Headquarters, IDL 26, Blenheim Building, Marlborough Lines, Andover, Hampshire, SP11 8HJ. The First World War sketch maps have been produced by the Defence Geographic Centre (DGC), Joint Force Intelligence Group (JFIG), Ministry of Defence, Elmwood Avenue, Feltham, Middlesex, TW13 7AH. United Kingdom. -

The Durham Light Infantry and the Somme 1916

The Durham Light Infantry and The Somme 1916 by John Bilcliffe edited and amended in 2016 by Peter Nelson and Steve Shannon Part 4 The Casualties. Killed in Action, Died of Wounds and Died of Disease. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License You can download this work and share it with others as long as it is credited, but you can’t change it in any way or use it commercially © John Bilcliffe. Email [email protected] Part 4 Contents. 4.1: Analysis of casualties sustained by The Durham Light Infantry on the Somme in 1916. 4.2: Officers who were killed or died of wounds on the Somme 1916. 4.3: DLI Somme casualties by Battalion. Note: The drawing on the front page of British infantrymen attacking towards La Boisselle on 1 July 1916 is from Reverend James Birch's war diary. DCRO: D/DLI 7/63/2, p.149. About the Cemetery Codes used in Part 4 The author researched and wrote this book in the 1990s. It was designed to be published in print although, sadly, this was not achieved during his lifetime. Throughout the text, John Bilcliffe used a set of alpha-numeric codes to abbreviate cemetery names. In Part 4 each soldier’s name is followed by a Cemetery Code and, where known, the Grave Reference, as identified by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Here are two examples of the codes and what they represent: T2 Thiepval Memorial A5 VII.B.22 Adanac Military Cemetery, Miraumont: Section VII, Row B, Grave no. -

James Anthony Horne 2Nd Lieutenant, 16 Th Battalion London Regiment (Queen’S Westminster Rifles) !

! James Anthony Horne 2nd Lieutenant, 16 th Battalion London Regiment (Queen’s Westminster Rifles) ! James Anthony Horne was born on 3 August 1892 and was baptised on 1 September that year in the Parish Church of St. James, Islington. The ceremony was performed by James’s father the Reverend Joseph White Horne, Vicar of St. James at that time. The family address is given as St. James Vicarage, Islington. In 1901 Joseph became Vicar at St. Mary Magdalene, Monkton, Kent, and the family, by this time including three children, took up residence in the Vicarage there. The Census of that year shows a nurse (domestic), a cook and two housemaids also resident at the Vicarage so the family obviously had plenty of help and lived in some comfort. Their stay in Monkton was fairly short however, and by 1905 they were living at Ivy House, High Street, Highgate, North London, where they were to remain until the outbreak of the war. They moved once more to reside briefly at Chesham Bois, Buckinghamshire, with Joseph by that time being retired, but returned to London, firstly to Highgate and subsequently to Kensington where he was to live out the remainder of his life. James received his secondary school education at Highgate School which he entered in September 1904. He left in July 1910 having been awarded a Choral Exhibition to Christ’s College, Cambridge. He studied there for four years gaining honours in both parts of the Theological Tripos and being awarded his B.A. Degree. As one would expect, he had a fine voice and he regularly performed as a member of a vocal quartet. -

1953 New Year Honours 1953 New Year Honours

12/19/2018 1953 New Year Honours 1953 New Year Honours The New Year Honours 1953 for the United Kingdom were announced on 30 December 1952,[1] to celebrate the year passed and mark the beginning of 1953. This was the first New Year Honours since the accession of Queen Elizabeth II. The Honours list is a list of people who have been awarded one of the various orders, decorations, and medals of the United Kingdom. Honours are split into classes ("orders") and are graded to distinguish different degrees of achievement or service, most medals are not graded. The awards are presented to the recipient in one of several investiture ceremonies at Buckingham Palace throughout the year by the Sovereign or her designated representative. The orders, medals and decorations are awarded by various honours committees which meet to discuss candidates identified by public or private bodies, by government departments or who are nominated by members of the public.[2] Depending on their roles, those people selected by committee are submitted to Ministers for their approval before being sent to the Sovereign for final The insignia of the Grand Cross of the approval. As the "fount of honour" the monarch remains the final arbiter for awards.[3] In the case Order of St Michael and St George of certain orders such as the Order of the Garter and the Royal Victorian Order they remain at the personal discretion of the Queen.[4] The recipients of honours are displayed here as they were styled before their new honour, and arranged by honour, with classes (Knight, Knight Grand Cross, etc.) and then divisions (Military, Civil, etc.) as appropriate. -

Annual Report of the Colonies, Kenya, 1934

COLONIAL REPORTS—ANNUAL No. 1722 Annual Report on the Social and Economic Progress of the People of the KENYA COLONY AND PROTECTORATE, 1934 (For Reports for 1932 and 1933 see Nos. 1659 and 168S respectively (Price 2s. od. each),) Cmvn Copyright Reserved LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses: Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120 George Street, Edinburgh 2) York Street, Manchester 1 j 1 St. Andrew's Crescent, Cardiff} 80 Chichester Street, Belfast| or through any Bookseller 1935 Price a;, od. Net 58-1722 ANNUAL REPORT ON THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC PROGRESS OF THE PEOPLE OF KENYA COLONY AND PROTECTORATE, 1934 CONTENTS PAGE I. GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE, AND HISTORY 2 II. GOVERNMENT 5 III. POPULATION 10 IV. HEALTH 13 V. HOUSING 15 VI. PRODUCTION 15 VII. COMMERCE 19 VIII. WAGES AND COST OF LIVING 29 IX. EDUCATION AND WELFARE INSTITUTIONS 31 X. COMMUNICATIONS AND TRANSPORT 33 XI. BANKING, CURRENCY, AND WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 38 XII. PUBLIC WORKS 39 XIII. JUSTICE, POLICE, AND PRISONS 40 XIV. LEGISLATION 44 XV. PUBLIC FINANCE AND TAXATION 46 APPENDIX. LIST OF SELECTED PUBLICATIONS 52 MAP. I.—GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE, AND HISTORY. Geography. The Colony and Protectorate of Kenya is traversed centrally from east to west by the Equator and from north to south by meridian line 37£° East of Greenwich. It extends from 4° North to 4° South of the Equator and from 34° East longitude to 41° East. The land area is 219,730 square miles and the water area includes the larger portion of Lake Rudolf and the eastern waters of Victoria Nyanza including the Kavirondo Gulf. -

The London Gazette, July 26, 1910

5400 THE LONDON GAZETTE, JULY 26, 1910. 4th Battalion, The Hampshire Regiment; Neville iQth (County of London) Battalion, The London- Reeks to be Second Lieutenant. Dated 27th Regiment (Paddington Rifles); Captain and May, 1910. Honorary Major Alfred D. Bayliffe to be- Frank Arthur Searle Hinton to be Second Major. Dated 28th June, 1910. Lieutenant. (To be supernumerary.) Dated Lieutenant William R. Walter to be Captain. 8th June, 1910. Dated 28th June, 1910. 6th Battalion, The South Staffordshire Regiment: 18^ (County of London) Battalion, The London George Henry Muras to be Second Lieu- Regiment (London Irish Rifles); Second Lieu- tenant. Dated 8th June, 1910. tenant Augustine ap Ellis to be Lieutenant. Dated 28th June, 1910. 4th Battalion. The Welsh Regiment; Arthur Stanley Williams to be Second Lieutenant. 23rd (County of London) Battalion, The London Dated 18th June, 1910. Regiment; the undermentioned officers are seconded, under the conditions of paragraph 6th (Glamorgan) Battalion, The Welsh Regiment; 114, Territorial Force Regulations:— Lieutenant Charles F. E. Gough to be Captain. Lieutenant Montgomery R.' Harris. Dated Dated 1st March, 1910. 20th November, 1909. oth Battalion, The Sherwood foresters {Notting- Lieutenant Roger J. Cholmeley. Dated 26tit hamshire and Derbyshire Regiment'); Second December, 1909. Lieutenant Frederick W. Wragg to be Lieu- Lieutenant Burton William Eills Getbing,. tenant. Dated 23rd January, 1910. The Northumberland Fusiliers, to be Adjutant, Lieutenant Frederick E. M. Doone to be vice Captain Thomas W. Bullock, The Dorset- Captain. Dated 1st April, 1910. shire Regiment, who vacates that appointment. Second Lieutenant Stewart J. Aldous to be Dated 12th July, 1910. Lieutenant. Dated 1st April, 1910.