Edward M. Eyring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Alumni Newsletter

ALUMNI NEWSLETTER SCHOOL OF CHEMICAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS at Urbana-Champaign NO. 11, WINTER 1976-77 The State of the Union (Comments by H. S. Gutowsky, director of the School of Chemical Sciences) Following the tradition of the last three issues of the Alumni Newsletter, I have put together a synopsis of some selected material that appears in much more detail in the 1975-76 Annual Report of the School of Chemical Sci ences and is not covered elsewhere in this issue. If you would like more details, let me know and I will be happy to forward you a copy of the com plete annual report. Instructional Program Two steps were taken dw·ing the past year to address the fact that 75 per cent or more of our chemistry graduates take positions in industry without learning much in their programs about the nature of industrial careers. Professor Peter Beak organized a special topics course, Chemistry 433, Re search in Industry, given in the fall semester. Early in the course, Dr. J. K. Stille from the University of Iowa presented a series of ten lectures on the fundamentals of industrial and polymer chemistry. This was followed by eleven weekly lectures from industrial speakers active in chemical roles. The program attracted a good deal of interest among our students and staff and its beneficial effects were visible to industrial recruiters interviewing here near its end. The second step was the inauguration of a cooperative program with Monsanto Company (St. Louis) for the summer employment of graduate students. Three entering graduate students participated in the summer of 1976, and it is hoped to extend the program to a larger number of students (and other companies) as well as to faculty next summer. -

Cold Fusion: Comments on the State of Scientific Proof

SPECIAL SECTION: LOW ENERGY NUCLEAR REACTIONS Cold fusion: comments on the state of scientific proof Michael C. H. McKubre* SRI International, Menlo Park, CA, USA examples of error given at any level of scientific sophisti- Early criticisms were made of the scientific claims made by Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons in cation. If pressed the authority of experts in the fields of 1989 on their observation of heat effects in electro- nuclear or particle physics are invoked, or early publica- chemically driven palladium–deuterium experiments tions of null results by ‘influential laboratories’ – that were consistent with nuclear but not chemical or Caltech, MIT, Bell Labs, Harwell. Almost to a man these stored energy sources. These criticisms were prema- experts have long ago retired or deceased, and the authors ture and adverse. In the light of 25 years further study of these early publications of ‘influential laboratories’ of the palladium–deuterium system, what is the state have long since left the field and not returned. The issue of proof of Fleischmann and Pons’ claims? of ‘long ago’ is important as it establishes a time window in which information was gathered sufficient for some to Keywords: Cold fusion, Fleischmann, Pons, scientific draw a permanent conclusion – some time between 23 proof. March 1989 and ‘long ago’. Absurdly for a matter of this seeming importance, ‘long ago’ usually dates to the Spring Meeting of the American Physical Society (APS) Introduction on 1 May 1989. So the whole matter was reported and then comprehensively dismissed within 40 days (and, THE question under discussion is whether the phenome- presumably, 40 nights). -

Tribute to Josef Michl

Editorial Editorial TributeTribute to JosefJosef Michl Michl IgorIgor Alabugin Alabugin 1,1,** andand Petr Petr Klán Klá n2,*2, * 1 1 Department of of Chemistry Chemistry and and Biochemistry, Biochemistry, Florida Florida State University,State University, Tallahassee, Tallahassee, Fl 32306, Fl USA 32306, USA 2 2 Department of of Chemistry Chemistry and and RECETOX, RECETOX, Faculty Faculty of Science, of Science, Masaryk Masa University,ryk University, Kamenice Kamenice 5, 5, 625 00 Brno,Brno, Czech Czech Republic Republic * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.A.); [email protected] (P.K.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.A.); [email protected] (P.K.) It is our great pleasure to introduce the Festschrift of Chemistry to honor professor JosefIt Michl is our (Figure great pleasure 1) on the to o introduceccasion of the hisFestschrift 80th birthdayof Chemistry and toto recognize honor professor his exceptional Josefcontributions Michl (Figure to 1the) on fields the occasion of organic of his photoc 80th birthdayhemistry, and quantum to recognize chemis his exceptionaltry, biradicals and contributionsbiradicaloids, to electronic the fields of and organic vibrational photochemistry, spectroscopy, quantum magnetic chemistry, circular biradicals dichroism, and sili- biradicaloids,con and boron electronic chemistry, and vibrational supramolecular spectroscopy, chem magneticistry, singlet circular fission, dichroism, and molecular silicon ma- andchines. boron chemistry, supramolecular chemistry, singlet fission, and molecular machines. -

Glass Shards • Page 2

GlassNEWSLETTER OF THE NATIONAL Shards AMERICAN GLASS CLUB www.glassclub.org Founded 1933 A Non-Profit Organization Summer 2016 News Highlights from the 2016 Seminar in Norfolk There were many wonderful experi- Museum. After her lecture, we were historic glassblowing techniques, blew ences that the attendees of the 2016 divided into two small groups and re- one of his favorite styles, a pillar- Seminar shared during the three-day ceived the rare opportunity of visiting molded pitcher. Although we have all gathering but a few events were high- the Ceramic and Glass Vault. Attend- seen glassblowing demonstrations lights of the Seminar. After visiting ees sat around tables and objects from countless times, Art, who was assisted the incredible home of Carolyn and the collection were discussed, passed by a Studio staff member, had the Richard Barry, filled with the amazing around, and handled. group captivated by working and art and spectacular contemporary glass, Another highlight was the glass- discussing each step in the process. the attendees traveled to the DeWitt blowing demonstration by NAGC Amazingly, Art had not blown a piece Wallace Museum of Decorative Arts Second Vice President Art Reed. The of glass for four years since concen- at Colonial Williamsburg. Chrysler Museum of Art acquired an trating on his wooden glassblowing Suzanne Hood, Curator of Ceramics old bank across the street from the block and mold business. and Glass at the Colonial Williamsburg museum and renovated the building Both the visit to Colonial Williams- Foundation (CWF) gave us an informa- into a glass studio. The Studio has be- burg’s DeWitt Wallace Museum of tive lecture about the glass collection come one of the most popular venues Decorative Arts and the glassblowing and why the CWF acquired the pieces. -

Glassblowers of Venice Kept Their Art So Secret That It Almost Died out by Associated Press, Adapted by Newsela Staff on 02.11.16 Word Count 620

Glassblowers of Venice kept their art so secret that it almost died out By Associated Press, adapted by Newsela staff on 02.11.16 Word Count 620 Glassblower William Gudenrath puts enamel on a bowl with techniques used by Renaissance Venetians at the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York, Jan. 22, 2016. Gudenrath spent decades researching how Renaissance glassmakers produced objects that are now considered works of art. Photo: AP/Mike Groll ALBANY, N.Y. — A modern-day glassblower believes he has unraveled the mysteries of Venetian glassmaking that was crafted during the Renaissance. The Renaissance was a cultural movement in Europe that lasted from the 1300s to the 1600s. During that period, glassmakers' secrets were closely guarded by the Venetian government. Anyone who spoke of them could be killed. Specially Skilled Craftsmen Today's glassblowers work with gas-fired furnaces and electric-powered ovens called kilns. Their studios are well lit and have proper air ventilation. The craftsmen of Murano, an island near Venice, Italy, did not have such technology. Yet they turned out pieces of art popular in museums today. The techniques, or the methods they used to make the objects, remained sought after for centuries. William Gudenrath spent years studying Venetian glass collections at American and European museums. He compared them with newer glasswork from Venice. He experimented on his own and traveled to Italy many times. Gudenrath combined all of his knowledge to produce an online guide. Guiding Modern Artists The guide is called "The Techniques of Renaissance Venetian Glassworking." It was recently posted on the website of the Corning Museum of Glass in New York. -

Calendar of Events

SEPTEMBER – OCTOBER, 2015 NEWSLETTER CALENDAR OF EVENTS CONFLUENCE Hired IRIS, PEONY AND UNIQUE The Master Plan Committee along with other interested stakeholders came together PLANT SALE over a four-month period and selected CONFLUENCE to provide master September 12 &13 plan services for the Arboretum. The committee reviewed fourteen proposals and interviewed three companies before selecting CONFLUENCE. Saturday & Sunday 9 a.m. – 4 p.m. CONFLUENCE was founded in Des Moines in 1998 and has since expanded throughout the Midwest, with additional offices in Cedar Find the best and brightest “stars” Rapids, Sioux Falls, Kansas City and Minneapolis. The company is for your garden. comprised of landscape architects and planners focused on bringing together people and ideas to create meaningful and memorable places within specific environments. PUMPKIN CARVING Thursday, October 15 Master planning is a collaborative process that consist of the evaluation 5 p.m. – 8:30 p.m. of current facilities, programs and services along with the long-term needs for facilities, programs and services. The finished product pulls Carve a pumpkin for displaying at together all of the elements desired for the Arboretum into a comprehensive the Arboretum’s Halloween events. plan. CONFLUENCE will also provide graphics to illustrate future Arboretum improvements. The master plan will be utilized to excite The Arboretum will provide dinner. and energize people about the Arboretum and be used as the road map for future development. AR “BOO” WEEN Committee Members: Dean Bowden, Don Draper, Donald Lewis, Saturday, October 17 Linda Grieve, Doug Gustafson, Wayne Koos, Kathy Law, Joe McNally, 1 p.m. -

November 2008 Ensign

THE ENSIGN OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF LATTER-DAY SAINTS • NOVEMBER 2008 General Conference Addresses Five New Temples Announced COURTESY OF HOPE GALLERY Christ Teaching Mary and Martha, by Anton Dorph The Savior “entered into a certain village: and a certain woman named Martha received him into her house. And she had a sister called Mary, which also sat at Jesus’ feet, and heard his word” (Luke 10:38–39). NOVEMBER 2008 • VOLUME 38 • NUMBER 11 2 Conference Summary for the 178th SUNDAY MORNING SESSION 100 Testimony as a Process Semiannual General Conference 68 Our Hearts Knit as One Elder Carlos A. Godoy President Henry B. Eyring 102 “Hope Ya Know, We Had SATURDAY MORNING SESSION 72 Christian Courage: The Price a Hard Time” 4 Welcome to Conference of Discipleship Elder Quentin L. Cook President Thomas S. Monson Elder Robert D. Hales 106 Until We Meet Again 7 Let Him Do It with Simplicity 75 God Loves and Helps All President Thomas S. Monson Elder L. Tom Perry of His Children 10 Go Ye Therefore Bishop Keith B. McMullin GENERAL RELIEF SOCIETY MEETING Silvia H. Allred 78 A Return to Virtue 108 Fulfilling the Purpose 13 You Know Enough Elaine S. Dalton of Relief Society Elder Neil L. Andersen 81 The Truth of God Shall Go Forth Julie B. Beck 15 Because My Father Read the Elder M. Russell Ballard 112 Holy Temples, Sacred Covenants Book of Mormon 84 Finding Joy in the Journey Silvia H. Allred Elder Marcos A. Aidukaitis President Thomas S. Monson 114 Now Let Us Rejoice 17 Sacrament Meeting and the Barbara Thompson Sacrament SUNDAY AFTERNOON SESSION 117 Happiness, Your Heritage Elder Dallin H. -

Melanie S. Sanford

Melanie S. Sanford Department of Chemistry University of Michigan Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Tel. (734) 615-0451 Fax (734) 647-4865 [email protected] Research Group: http://www.umich.edu/~mssgroup/ EDUCATION: Ph.D., Chemistry June 2001 California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA Thesis Title: Synthetic and Mechanistic Investigations of Ruthenium Olefin Metathesis Catalysts B.S.; M.S. cum laude with Distinction in Chemistry June 1996 Yale University, New Haven, CT CURRENT POSITION: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI Moses Gomberg Distinguished University Professor of Chemistry September 2016 – present Arthur F. Thurnau Professor of Chemistry July 2011 – present PREVIOUS POSITIONS: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI Moses Gomberg Collegiate Professor of Chemistry January 2012 – Sept 2016 Professor of Chemistry September 2010 – June 2011 Associate Professor of Chemistry May 2007 – August 2010 William R. Roush Assistant Professor of Chemistry October 2006 – May 2007 Assistant Professor of Chemistry July 2003 – October 2006 Princeton University, Princeton, NJ NIH NRSA Postdoctoral Fellow August 2001 – June 2003 Advisor: Professor John T. Groves California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA Graduate Student August 1997 – July 2001 Advisor: Professor Robert H. Grubbs Yale University, New Haven, CT Undergraduate Student September 1994 – June 1996 Advisor: Professor Robert H. Crabtree Naval Research Laboratory, Washington, DC Summer Intern Summer 2003, 2004, 2005 Advisor: Dr. David W. Conrad AWARDS: Honorary Doctorate, University of South -

Page 1 of 56 in the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for THE

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA CITY OF PHILADELPHIA, : GUARDIAN CIVIC LEAGUE OF : CIVIL ACTION NO. PHILADELPHIA, ASPIRA, INC. OF : PENNSYLVANIA, RESIDENTS : 2000-CV-2463 ADVISORY BOARD, NORTHEAST : HOME SCHOOL AND BOARD, and : PHILADELPHIA CITIZENS FOR : CHILDREN AND YOUTH, : : Plaintiffs; : : v. : : BERETTA U.S.A., CORP., : BROWNING, INC., BRYCO ARMS, : INC., COLT’S MANUFACTURING : CO., GLOCK, INC., HARRINGTON & : RICHARDSON, INC., : INTERNATIONAL ARMAMENT : INDUSTRIES, INC., KEL-TEC, CNC, : LORCIN ENGINEERING CO., : NAVEGAR, INC., PHOENIX/RAVEN : ARMS, SMITH & WESSON CORP., : STURM, RUGER & CO., and TAURUS : INTERNATIONAL FIREARMS, : ET AL., : : Defendants. : O P I N I O N Date: December 20, 2000 Schiller, J. Page 1 of 56 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................. 3 STANDARD FOR MOTION TO DISMISS ......................................... 4 REGULATION OF FIREARMS .................................................. 5 FACTS ALLEGED IN THE COMPLAINT ......................................... 6 DISCUSSION ................................................................ 8 I. Philadelphia’s suit is barred by the Uniform Firearms Act (“UFA”) .......... 8 A. Section 6120 ................................................ 8 B. Section 6120(a.1) (“UFA Amendment”) ......................... 10 1. Plain meaning ........................................ 10 2. Impetus for statute .................................... 11 3. Legislative history ................................... -

George Porter

G EORGE P O R T E R Flash photolysis and some of its applications Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1967 One of the principal activities of man as scientist and technologist has been the extension of the very limited senses with which he is endowed so as to enable him to observe phenomena with dimensions very different from those he can normally experience. In the realm of the very small, microscopes and micro- balances have permitted him to observe things which have smaller extension or mass than he can see or feel. In the dimension of time, without the aid of special techniques, he is limited in his perception to times between about one twentieth of a second ( the response time of the eye) and about 2·10 9 seconds (his lifetime). Y et most of the fundamental processes and events, particularly those in the molecular world which we call chemistry, occur in milliseconds or less and it is therefore natural that the chemist should seek methods for the study of events in microtime. My own work on "the study of extremely fast chemical reactions effected by disturbing the equilibrium by means of very short pulses of energy" was begun in Cambridge twenty years ago. In 1947 I attended a discussion of the Faraday Society on "The Labile Molecule". Although this meeting was en- tirely concerned with studies of short lived chemical substances, the four hundred pages of printed discussion contain little or no indication of the im- pending change in experimental approach which was to result from the intro- . -

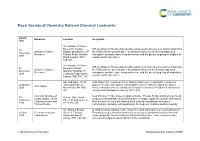

RSC Branding

Royal Society of Chemistry National Chemical Landmarks Award Honouree Location Inscription Date The Institute of Cancer Research, Chester ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Institute of Cancer Beatty Laboratories, 237 the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Research Fulham Road, Chelsea carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Road, London, SW3 ovarian and breast cancer. 6JB, UK The Institute of Cancer ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Research, Royal Institute of Cancer the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Marsden Hospital, 15 Research carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Cotswold Road, Sutton, ovarian and breast cancer. London, SM2 5NG, UK Ape and Apple, 28-30 John Dalton Street was opened in 1846 by Manchester Corporation in honour of 26 October John Dalton Street, famous chemist, John Dalton, who in Manchester in 1803 developed the Atomic John Dalton 2016 Manchester, M2 6HQ, Theory which became the foundation of modern chemistry. President of Manchester UK Literary and Philosophical Society 1816-1844. Chemical structure of Near this site in 1903, James Colquhoun Irvine, Thomas Purdie and their team found 30 College Gate, North simple sugars, James a way to understand the chemical structure of simple sugars like glucose and lactose. September Street, St Andrews, Fife, Colquhoun Irvine and Over the next 18 years this allowed them to lay the foundations of modern 2016 KY16 9AJ, UK Thomas Purdie carbohydrate chemistry, with implications for medicine, nutrition and biochemistry.