K. Savage, “The Self-Made Monument: George Washington and the Fight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

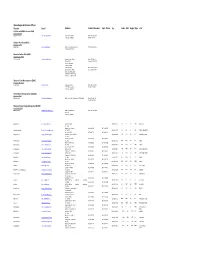

Alaska Regional Directors Offices Director Email Address Contact Numbers Supt

Alaska Regional Directors Offices Director Email Address Contact Numbers Supt. Phone Fax Code ABLI RegionType Unit U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) Alaska Region (FWS) HASKETT,GEOFFREY [email protected] 1011 East Tudor Road Phone: 907‐ 786‐3309 Anchorage, AK 99503 Fax: 907‐ 786‐3495 Naitonal Park Service(NPS) Alaska Region (NPS) MASICA,SUE [email protected] 240 West 5th Avenue,Suite 114 Phone:907‐644‐3510 Anchoorage,AK 99501 Bureau of Indian Affairs(BIA) Alaska Region (BIA) VIRDEN,EUGENE [email protected] Bureau of Indian Affairs Phone: 907‐586‐7177 PO Box 25520 Telefax: 907‐586‐7252 709 West 9th Street Juneau, AK 99802 Anchorage Agency Phone: 1‐800‐645‐8465 Bureau of Indian Affairs Telefax:907 271‐4477 3601 C Street Suite 1100 Anchorage, AK 99503‐5947 Telephone: 1‐800‐645‐8465 Bureau of Land Manangement (BLM) Alaska State Office (BLM) CRIBLEY,BUD [email protected] Alaska State Office Phone: 907‐271‐5960 222 W 7th Avenue #13 FAX: 907‐271‐3684 Anchorage, AK 99513 United States Geological Survey(USGS) Alaska Area (USGS) BARTELS,LESLIE lholland‐[email protected] 4210 University Dr., Anchorage, AK 99508‐4626 Phone:907‐786‐7055 Fax: 907‐ 786‐7040 Bureau of Ocean Energy Management(BOEM) Alaska Region (BOEM) KENDALL,JAMES [email protected] 3801 Centerpoint Drive Phone: 907‐ 334‐5208 Suite 500 Anchorage, AK 99503 Ralph Moore [email protected] c/o Katmai NP&P (907) 246‐2116 ANIA ANTI AKR NPRES ANIAKCHAK P.O. Box 7 King Salmon, AK 99613 (907) 246‐3305 (907) 246‐2120 Jeanette Pomrenke [email protected] P.O. -

Building Stones of the National Mall

The Geological Society of America Field Guide 40 2015 Building stones of the National Mall Richard A. Livingston Materials Science and Engineering Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA Carol A. Grissom Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA Emily M. Aloiz John Milner Associates Preservation, 3200 Lee Highway, Arlington, Virginia 22207, USA ABSTRACT This guide accompanies a walking tour of sites where masonry was employed on or near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It begins with an overview of the geological setting of the city and development of the Mall. Each federal monument or building on the tour is briefly described, followed by information about its exterior stonework. The focus is on masonry buildings of the Smithsonian Institution, which date from 1847 with the inception of construction for the Smithsonian Castle and continue up to completion of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. The building stones on the tour are representative of the development of the Ameri can dimension stone industry with respect to geology, quarrying techniques, and style over more than two centuries. Details are provided for locally quarried stones used for the earliest buildings in the capital, including A quia Creek sandstone (U.S. Capitol and Patent Office Building), Seneca Red sandstone (Smithsonian Castle), Cockeysville Marble (Washington Monument), and Piedmont bedrock (lockkeeper's house). Fol lowing improvement in the transportation system, buildings and monuments were constructed with stones from other regions, including Shelburne Marble from Ver mont, Salem Limestone from Indiana, Holston Limestone from Tennessee, Kasota stone from Minnesota, and a variety of granites from several states. -

Founding Fathers" in American History Dissertations

EVOLVING OUR HEROES: AN ANALYSIS OF FOUNDERS AND "FOUNDING FATHERS" IN AMERICAN HISTORY DISSERTATIONS John M. Stawicki A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2019 Committee: Andrew Schocket, Advisor Ruth Herndon Scott Martin © 2019 John Stawicki All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This thesis studies scholarly memory of the American founders and “Founding Fathers” via inclusion in American dissertations. Using eighty-one semi-randomly and diversely selected founders as case subjects to examine and trace how individual, group, and collective founder interest evolved over time, this thesis uniquely analyzes 20th and 21st Century Revolutionary American scholarship on the founders by dividing it five distinct periods, with the most recent period coinciding with “founders chic.” Using data analysis and topic modeling, this thesis engages three primary historiographic questions: What founders are most prevalent in Revolutionary scholarship? Are social, cultural, and “from below” histories increasing? And if said histories are increasing, are the “New Founders,” individuals only recently considered vital to the era, posited by these histories outnumbering the Top Seven Founders (George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Paine) in founder scholarship? The thesis concludes that the Top Seven Founders have always dominated founder dissertation scholarship, that social, cultural, and “from below” histories are increasing, and that social categorical and “New Founder” histories are steadily increasing as Top Seven Founder studies are slowly decreasing, trends that may shift the Revolutionary America field away from the Top Seven Founders in future years, but is not yet significantly doing so. -

National Treasure Movie Study.Pdf

Terms of use © Copyright 2019 Learn in Color. All rights reserved. All rights reserved. This file is for personal and classroom use only. You are not allowedto re- sell this packet or claim it as your own. You may not alter this file. You may photocopy it only for personal, non-commercial uses, such as your immediate family or classroom. If you have any questions, comments, problems, or future product suggestions, feel free to shoot me an e-mail! :) Movie Studies: Novel Studies: • The Courageous Heart of Irena Sendler • I Am David by Anne Holm • The Emperor’s New Groove • Louisiana’s Way Home by Kate DiCa- • The Giver millo • The Greatest Showman • Merci Suarez Changes Gears by Meg • Holes Medina • Life is Beautiful • Peter Nimble and His Fantastic Eyes • Meet the Robinsons by Jonathan Auxier • Mulan • Projekt 1065 by Alan Gratz • Newsies • Sweep by Jonathan Auxier • The Pursuit of Happyness • And more! • Secondhand Lions • The Sound of Music • Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory • The Zookeeper’s Wife • And more! Created by Samantha Shank E-mail: [email protected] Website: learnincolor.com Teachers Pay Teachers: teacherspayteachers.com/Store/Learn-In-Color Join facebook.com/learnincolormy Facebook community! Name: ________________________________________ 1. What is the Charlotte? Movie Quiz A. A train B. A car C. A ship D. An airplane 2. What do Ben, Riley, and Ian find on the Charlotte? A. A pipe B. A map C. Glasses D. A book 3. On the Charlotte, who wants to steal the Declaration of Independence? A. Ben B. Riley C. Sadusky D. -

George Washington: a New Man for a New Century

GEORGE WASHINGTON: A NEW MAN FOR A NEW CENTURY By Barry Schwartz George Washington never tolerated the notion, flaunted by some of his successors in the Presidential chair that the voice of the people, whatever its tone or its message, is the voice of God; nor was his political philosophy summed up in “keeping his ear to the ground, ” in order to catch from afar the ramblings of popular approval or dissent.... Will any one say that there is no need of such men now, or that the common people would not hear them gladly if once it were known that they dwelt among us? —The Nation, 18891 Every conception of the past is construed from the standpoint of the concerns and needs of the present.”2 Could the sociologist George Herbert Mead’s statement be applied to George Washington at the 1899 centennial of his death? Was Washington the same man at the turn of the twentieth century, when America was becoming an industrial democracy, as he was at the turn of the nineteenth, when the nation was still a rural republic? The title of the present essay suggests that the question has already been answered, but the matter is more complex than that. Because any historical object appears differently against a new background, Washington’s character and achievements necessarily assumed new meaning from the Jacksonian era and Civil War through the Industrial Revolution. Washington’s changing image, however, is only one part of this story. Focusing on the first two decades of the twentieth century, the other part of the story—“Washington’s unchanging image”—must also be considered. -

INDEX HB Pages Qfinal Copy 1 8/12/02 10:55 PM Page 1 the National Parks: Index 2001-2003

INDEX_HB_Pages_QFinal copy 1 8/12/02 10:55 PM Page 1 The National Parks: Index 2001-2003 Revised to Include the Actions of the 106th Congress ending December 31, 2000 Produced by the Office of Public Affairs and Harpers Ferry Center Division of Publications National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 1 INDEX_HB_Pages_QFinal copy 1 8/12/02 10:55 PM Page 2 About this Book This index is a complete administrative listing of the National Park System’s areas and related areas. It is revised biennially to reflect congressional actions. The entries, grouped by state, include administrative addresses and phone numbers, dates of au- thorization and establishment, boundary change dates, acreages, and brief statements explaining the areas’ national significance. This book is not intended as a guide for park visitors. There is no information regarding campgrounds, trails, visitor services, hours, etc. Those needing such information can visit each area’s web site, accessible through the National Park Service ParkNet home page (www.nps.gov). The Mission of the National Park Service The National Park Service preserves unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future genera- tions. The National Park Service cooperates with partners to extend the benefits of natural and cultural resource conservation and outdoor recreation throughout this country and the world. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing -

The Representation of Minorities in American Musical Theater Since the 1950S

The Representation of Minorities in American Musical Theater since the 1950s Krstičević, Klara Master's thesis / Diplomski rad 2020 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: University of Zagreb, University of Zagreb, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:131:689147 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-23 Repository / Repozitorij: ODRAZ - open repository of the University of Zagreb Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Odsjek za anglistiku Filozofski fakultet Sveučilište u Zagrebu DIPLOMSKI RAD The Representation of Minorities in American Musical Theater since the 1950s (Smjer: Američka književnost i kultura) Kandidat: Klara Krstičević Mentor: dr. sc. Jelena Šesnić Ak. godina: 2019./2020. 1 Contents 1. Introduction .....................................................................................................................2 2. African Americans in representations and productions of Broadway musicals .................8 2.1. Hello, Dolly! ................................................................................................................9 2.2. Hamilton: An American Musical ................................................................................ 12 3. An overview of the history of Puerto Rican representation on Broadway ................ 19 3.1.West Side Story .......................................................................................................... -

Washington Monument Visitor Security Screening

NATIONAL PARK U.S. Department of the Interior SERVICE National Park Service Washington Monument Visitor Security Screening E N V I R O N M E N T A L A S S E S S ME N T July 2013 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL MALL AND MEMORIAL PARKS WASHINGTON, D.C. Washington Monument Visitor Security Screening National Mall and Memorial Parks ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT July, 2013 [This page intentionally left blank.] PROJECT SUMMARY The National Park Service (NPS), in cooperation with the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) has prepared this Environmental Assessment (EA) to evaluate a range of alternatives for the enhancement and improvement of the visitor screening at the Washington Monument (the Monument) in Washington, D.C. The National Mall is a highly recognizable space and one of the most significant historic landscapes in the United States, extending east to west from the U.S. Capitol building to the Potomac River and north to south from Constitution Avenue, NW to the Thomas Jefferson Memorial. The Washington Monument is the central point of the National Mall, placed at the intersection of two significant axes between the U.S. Capitol and the Lincoln Memorial to the east-west and the White House to the Jefferson Memorial to the north-south. The Washington Monument is made up of a stone masonry obelisk set within a circular granite plaza and flanked by large turf expanses. As the primary memorial to the nation’s first president, the Monument is one of the most prominent icons in the nation and is toured by approximately one million visitors annually with millions more visiting the surrounding grounds. -

200-Year-Old Cornerstone Discovered During Baltimore's

DATE: February 16, 2015 CONTACT: Cathy Rosenbaum Mount Vernon Place Conservancy [email protected] 410-560-0180 443-904-4861 mobile FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 200-Year-Old Cornerstone Discovered During Baltimore’s Washington Monument Restoration th Contents Revealed Wednesday, February 18 at 1:00 pm (Baltimore, Maryland) – Today, the Mount Vernon Place Conservancy (Conservancy) reports that it believes the original cornerstone of the Washington Monument has been discovered. It likely has a hollowed out well in the granite base in which items were deposited during the cornerstone ceremony on July 4, 1815. On Wednesday, February 18th at 1:00 pm, the Mount Vernon Place Conservancy invites the press to be on-site at the Washington Monument (699 N. Charles Street, Baltimore, MD 21201) when the two-hundred-year old contents of the cornerstone will be revealed. The laying of the cornerstone in 1815 was of national interest because Baltimore’s Washington Monument was the first American monument dedicated to the Father of American democracy. Interestingly, the cornerstone laying ceremony was well documented, but the location of the cornerstone was not mentioned, and its location had been lost to time. The stone was discovered while George Wilk, II, Project Superintendent for Lewis Contractors, was overseeing the digging of a pit for a sewage tank off the northeast corner of the building. The cornerstone is a large square of granite with a marble lid. Its overall dimensions form a nearly-perfect cube measuring 24 inches. Conservators from the nearby Walters Art Museum will assist in removing the contents of the cornerstone. Accounts mention papers items and coinage, typical cornerstone offerings at the time. -

The Washington Monument... an Authentic History of Its Origin And

= 2Q3 .4 .U3 D5 Copy 2 f rtrt t$h dh "The Republic may perish; the wide arch of our ranged Union may f ali ; star by star its glories may expire ; stone after stone its columns and its capital may moulder and adorn its crumble ; all other names which annals may be forgotten; but as long as human hearts shall anywhere pant, or hu- man tongues shall anywhere plead for a true, rational, constitutional liberty, those hearts shall enshrine the memory, and those tongues shall prolong the fame of GeorgeWashington." the laying of the ( Robert C. Winthrop, in his oration at cornerstone of the Monument, July 4, 1848.) w <-yp ^ *i J.S Washington Monument An authentic history of its origin and construction, ' and a complete description of its memorial tablets £epyrigftt, mo The Caroline Publishing Co, i 521 Caroline Street, Washington, D. C. : Washington, D. G,- - - - 190 CS)I$ is lo gerflfy tfcat M of this day visited the Washington Monument. SEAL "Witnesses By transfer OCT 11 J915 "HE WA5HINQT0N faONCIttENT. HE Washington Monument occupies a promi- nent site near the banks of the Potomac, west of the Mall, at the former confluence of the Tiber with the main stream, and half a mile due south of the Executive Mansion. It stands on a terrace 17 feet high. The square of 41 acres in which the Monument stands was designated on L'Enfant's plan of the City of Washington as the site for the proposed Monument to Washington, which was ordered by the Continental Congress in 1783 and ap- proved by Washington himself. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Neoliberalism, Citizenship, and the Spectacle of Democracy in American Film and Television, 1973-2016 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television by Alice Elizabeth Royer 2018 © Copyright by Alice Elizabeth Royer 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Neoliberalism, Citizenship, and the Spectacle of Democracy in American Film and Television, 1973-2016 by Alice Elizabeth Royer Doctor of Philosophy in Film and Television University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor William McDonald, Co-Chair Professor Johanna R Drucker, Co-Chair This dissertation examines American films, miniseries, and television shows that center on the democratic process, mobilizing it in the service of stories that both provide intense narrative and visual pleasures, and offer satisfaction in the form of apparent knowledge gained about the inner workings of electoral politics in the United States; these media texts are here theorized as “democracy porn.” Significantly, democracy porn emerges alongside neoliberalism, and its proliferation mirrors that ideology’s meteoric rise to prominence. As such, the dissertation considers texts made since the advent of neoliberalism in 1973, and up to the US presidential election of 2016, which marks a major shift in the meanings and values associated with democracy porn. Through historical, textual, and discourse analysis drawing on critical theories of affect, citizenship, and neoliberalism, the dissertation interrogates the complex ways in which democracy porn is constructed and functions within and surrounding moving image ii texts. The project thus tracks the ways neoliberal ideology manifests in the media texts in question, as well as how the consumption of these texts impacts viewers’ understandings of their own citizenship within a democracy increasingly steered by neoliberal principles. -

Build the Washington Monument

Build Your Own Washington Monument! Built to honor George Washington, the United States' frst president, the 555 foot (169 m) marble obelisk towers over our Nation's Capital, Washington, D.C. The monument was designed by American Architect. Robert Mills and completed by Thomas Casey and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Fun Fact! Its walls are 15 feet (4.6 m) thick at its base and 1 1/2 feet (0.46 m) thick at the top. Wow! West South Tab Front Door East Instructions: North Tab Fold over this tab and tape or glue it to theStep outside of 1: the Cutwest wall. along the outside outline including the dashed tabs Step 2: Fold the pyramidian (tip) so that the triangular ends form a peak. Use the tab to tape or glue the top together. Fold Step 3: Fold along each wall. Step 4: Tape or glue the large tab to the outside of the West wall. Step 5: Tape or glue your completed monument on the site plane (base) found on the next page using the tabs The Washington Monument WEST Lincoln Memorial Washington, D.C. HABS DC-428 HABS DC-3 What's Inside? The interior has iron stairs that spiral up along the walls to the top. There is also an elevator in the center. Whew! Imagine climbing all those stairs. Put Tab Here Here Put Tab Did You Notice? SOUTH NORTH Jefferson Memorial Obelisk Goes Here White House HABS DC-4 HABS DC-37 The pattern and lengths of many of the Put Tab Here Here Put Tab stones on the each side of the obelisk change.