The Representation of Minorities in American Musical Theater Since the 1950S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OSLO Big Winner at the 2017 Lucille Lortel Awards, Full List! by BWW News Desk May

Click Here for More Articles on 2017 AWARDS SEASON OSLO Big Winner at the 2017 Lucille Lortel Awards, Full List! by BWW News Desk May. 7, 2017 Tweet Share The Lortel Awards were presented May 7, 2017 at NYU Skirball Center beginning at 7:00 PM EST. This year's event was hosted by actor and comedian, Taran Killam, and once again served as a benefit for The Actors Fund. Leading the nominations this year with 7 each are the new musical, Hadestown - a folk opera produced by New York Theatre Workshop - and Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, currently at the Barrow Street Theatre, which has been converted into a pie shop for the intimate staging. In the category of plays, both Paula Vogel's Indecent and J.T. Rogers' Oslo, current Broadway transfers, earned a total of 4 nominations, including for Outstanding Play. Playwrights Horizons' A Life also earned 4 total nominations, including for star David Hyde Pierce and director Anne Kauffman, earning her 4th career Lortel Award nomination; as did MCC Theater's YEN, including one for recent Academy Award nominee Lucas Hedges for Outstanding Lead Actor. Lighting Designer Ben Stanton earned a nomination for the fifth consecutive year - and his seventh career nomination, including a win in 2011 - for his work on YEN. Check below for live updates from the ceremony. Winners will be marked: **Winner** Outstanding Play Indecent Produced by Vineyard Theatre in association with La Jolla Playhouse and Yale Repertory Theatre Written by Paula Vogel, Created by Paula Vogel & Rebecca Taichman Oslo **Winner** Produced by Lincoln Center Theater Written by J.T. -

Case Study: Multiverse Wireless DMX at Hadestown on Broadway

CASE STUDY: Multiverse Wireless DMX Jewelle Blackman, Kay Trinidad, and Yvette Gonzalez-Nacer in Hadestown (Matthew Murphy) PROJECT SNAPSHOT Project Name: Hadestown on Broadway Location: Walter Kerr Theatre, NY, NY Hadestown is an exciting Opening Night: April 17, 2019 new Broadway musical Scenic Design: Rachel Hauck (Tony Award) that takes the audience Lighting Design: Bradley King (Tony Award) on a journey to Hell Associate/Assistant LD: John Viesta, Alex Mannix and back. Winner of eight 2019 Tony Awards, the show Lighting Programmer: Bridget Chervenka Production Electrician: James Maloney, Jr. presents the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice set to its very Associate PE: Justin Freeman own distinctive blues stomp in the setting of a low-down Head Electrician: Patrick Medlock-Turek New Orleans juke joint. For more information, read the House Electrician: Vincent Valvo Hadestown Review in Lighting & Sound America. Follow Spot Operators: Paul Valvo, Mitchell Ker Lighting Package: Christie Lites City Theatrical Solutions: Multiverse® 900MHz/2.4GHz Transmitter (5910), QolorFLEX® 2x0.9A 2.4GHz Multiverse Dimmers (5716), QolorFLEX SHoW DMX Neo® 2x5A Dimmers, DMXcat® CHALLENGES SOLUTION One of the biggest challenges for shows in Midtown Manhattan City Theatrical’s Multiverse Transmitter operating in the 900MHz looking to use wireless DMX is the crowded spectrum. With every band was selected to meet this challenge. The Multiverse lighting cue on stage being mission critical, a wireless DMX system – Transmitter provided DMX data to battery powered headlamps. especially one requiring a wide range of use, compatibility with other A Multiverse Node used as a transmitter and operating on a wireless and dimming control systems, and size restraints – needs SHoW DMX Neo SHoW ID also broadcast to QolorFlex Dimmers to work despite its high traffic surroundings. -

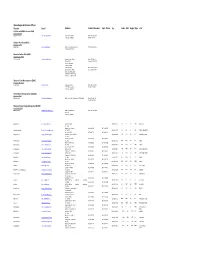

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Alaska Regional Directors Offices Director Email Address Contact Numbers Supt

Alaska Regional Directors Offices Director Email Address Contact Numbers Supt. Phone Fax Code ABLI RegionType Unit U.S Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) Alaska Region (FWS) HASKETT,GEOFFREY [email protected] 1011 East Tudor Road Phone: 907‐ 786‐3309 Anchorage, AK 99503 Fax: 907‐ 786‐3495 Naitonal Park Service(NPS) Alaska Region (NPS) MASICA,SUE [email protected] 240 West 5th Avenue,Suite 114 Phone:907‐644‐3510 Anchoorage,AK 99501 Bureau of Indian Affairs(BIA) Alaska Region (BIA) VIRDEN,EUGENE [email protected] Bureau of Indian Affairs Phone: 907‐586‐7177 PO Box 25520 Telefax: 907‐586‐7252 709 West 9th Street Juneau, AK 99802 Anchorage Agency Phone: 1‐800‐645‐8465 Bureau of Indian Affairs Telefax:907 271‐4477 3601 C Street Suite 1100 Anchorage, AK 99503‐5947 Telephone: 1‐800‐645‐8465 Bureau of Land Manangement (BLM) Alaska State Office (BLM) CRIBLEY,BUD [email protected] Alaska State Office Phone: 907‐271‐5960 222 W 7th Avenue #13 FAX: 907‐271‐3684 Anchorage, AK 99513 United States Geological Survey(USGS) Alaska Area (USGS) BARTELS,LESLIE lholland‐[email protected] 4210 University Dr., Anchorage, AK 99508‐4626 Phone:907‐786‐7055 Fax: 907‐ 786‐7040 Bureau of Ocean Energy Management(BOEM) Alaska Region (BOEM) KENDALL,JAMES [email protected] 3801 Centerpoint Drive Phone: 907‐ 334‐5208 Suite 500 Anchorage, AK 99503 Ralph Moore [email protected] c/o Katmai NP&P (907) 246‐2116 ANIA ANTI AKR NPRES ANIAKCHAK P.O. Box 7 King Salmon, AK 99613 (907) 246‐3305 (907) 246‐2120 Jeanette Pomrenke [email protected] P.O. -

Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: the Musical Katherine B

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 "Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The Musical Katherine B. Marcus Reker Scripps College Recommended Citation Marcus Reker, Katherine B., ""Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The usicalM " (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 876. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/876 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CAN WE DO A HAPPY MUSICAL NEXT TIME?”: NAVIGATING BRECHTIAN TRADITION AND SATIRICAL COMEDY THROUGH HOPE’S EYES IN URINETOWN: THE MUSICAL BY KATHERINE MARCUS REKER “Nothing is more revolting than when an actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing.” – Bertolt Brecht SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS GIOVANNI ORTEGA ARTHUR HOROWITZ THOMAS LEABHART RONNIE BROSTERMAN APRIL 22, 2016 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the support of the entire Faculty, Staff, and Community of the Pomona College Department of Theatre and Dance. Thank you to Art, Sherry, Betty, Janet, Gio, Tom, Carolyn, and Joyce for teaching and supporting me throughout this process and my time at Scripps College. Thank you, Art, for convincing me to minor and eventually major in this beautiful subject after taking my first theatre class with you my second year here. -

JOSEPH SCHMIDT Musical Direction By: EMILY BENGELS Choreography By: KRISTIN SARBOUKH

Bernards Township Parks & Recreation and Trilogy Repertory present... 2021 Produced by: JAYE BARRE Directed by: JOSEPH SCHMIDT Musical Direction by: EMILY BENGELS Choreography by: KRISTIN SARBOUKH Book by THOMAS MEEHAN Music by CHARLES STROUSE Lyrics by MARTIN CHARNIN Original Broadway production directed by MARTIN CHARNIN. Based on “Little Orphan Annie.” By permission of Tribune Content Agency, LLC. ANNIE is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are supplied by MTI. www.MTIShows.com This production is dedicated to the memory of beloved Trilogy Repertory member Chris Winans who gave of his time and spirit for many years and in many performances. Chris was a valued member of our Trilogy family and will be greatly missed. Summer, 2021 Dear Residents and Friends of the Community, Good evening and welcome to the Bernards Township Department of Parks and Recreation’s 34th season of Plays in the Park. So many of you enjoy and look forward to the plays year after year. I am excited that the Township brings this tradition free to the public for all to enjoy. Bernards Township proudly sponsors this event and substantially subsidizes the budget because we recognize the importance of keeping performing arts alive. It is truly wonderful that these productions are here, under the stars, in Pleasant Valley Park. Bernards Township offers many opportunities to enjoy family outings such as Plays In The Park. You can stay current on all our special events by visiting our website at www.bernards.org. There you will find information on the wide variety of programs we offer. -

2021/2022 Season Announcement

For immediate release Publicist: Brian McWilliams [email protected] SAN FRANCISCO PLAYHOUSE ANNOUNCES 2021-2022 SEASON First full in-person season since COVID-19 pandemic to feature THE GREAT KHAN, TWELFTH NIGHT, HEROES OF THE FOURTH TURNING, THE PAPER DREAMS OF HARRY CHIN, WATER BY THE SPOONFUL, and FOLLIES SAN FRANCISCO (July 11, 2021) — San Francisco Playhouse (Artistic Director Bill English; Producing Director Susi Damilano) announced today the six plays that will comprise its 2021/22 Season. In announcing their first full in-person season since the COVID-19 pandemic shut down production in March 2020, the company reasserted its commitment to producing bold, challenging, and uplifting plays and musicals for the Bay Area community. “We feel passionately that coming at this moment in American history, our 19th Season may well be our most important,” said Bill English, Artistic Director. “We will joyfully collaborate with artists who speak from widely unique perspectives on universal themes that generate greater empathy and compassion. It is in this spirit that we present our 2021/22 Season, which spans from a world premiere to the San Francisco professional premiere of a Sondheim classic. This season focuses on plays that show us the light at the end of the tunnel, that help us believe that hope and redemption are within our reach.” Mainstage The San Francisco Playhouse 2021/22 Season will begin with the World Premiere of The Great Khan by veteran Bay Area playwright and actor Michael Gene Sullivan, followed by Kwame Kwei-Armah and Shaina Taub’s musical adaptation of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night. -

Broadway Guest Artists & High-Profile Key Note Speakers

Broadway Guest Artists & High-Profile Key Note Speakers George Hamilton, Broadway and Film Actor, Broadway Actresses Charlotte D’Amboise & Jasmine Guy speaks at a Chicago Day on Broadway speak at a Chicago Day on Broadway Fashion Designer, Tommy Hilfiger, speaks at a Career Day on Broadway AMY WEINSTEIN PRESIDENT, CEO AND FOUNDER OF STUDENTSLIVE Amy Weinstein has been developing, creating, marketing and producing education programs in partnership with some of the finest Broadway Artists and Creative teams since 1998. A leader and pioneer in curriculum based standards and exciting and educational custom designed workshops and presentations, she has been recognized as a cutting edge and highly effective creative presence within public and private schools nationwide. She has been dedicated to arts and education for the past twenty years. Graduating from New York University with a degree in theater and communication, she began her work early on as a theatrical talent agent and casting director in Hollywood. Due to her expertise and comprehensive focus on education, she was asked to teach acting to at-risk teenagers with Jean Stapleton's foundation, The Academy of Performing and Visual Arts in East Los Angeles. Out of her work with these artistically talented and gifted young people, she co-wrote and directed a musical play entitled Second Chance, which toured as an Equity TYA contract to over 350,000 students in California and surrounding states. National mental health experts recognized the play as an inspirational arts model for crisis intervention, and interpersonal issues amongst teenagers at risk throughout the country. WGBH/PBS was so impressed with the play they commissioned it for adaptation to teleplay in 1996. -

Hammy Collage Pittsburgh

... ,-. ,// ./- ,-.,.:-.-: Hamilton’s Plot Point Problems (an incomplete list) - The two main characters, Hamilton and Burr, barely knew each other during the war years; their paths rarely crossed. - Alexander Hamilton did not punch the bursar at Princeton College. - Hamilton did not carouse at a tavern with Mulligan, Lafayette, and Laurens in 1776 and Sam Adams, who Miranda name-checks as the brewer of the beer at that pub, is a reference to a brewing company that wasn’t established until 1984. In truth, Hamilton met Mulligan, Lafayette, and Laurens separately, several years after 1776. - Angelica Schuyler sings that “My father has no sons so I’m the one / Who has to social climb.” That’s nonsense. In 1776, Philip Schuyler had three sons. - Angelica Schuyler was married her rich British husband before she ever met Alexander Hamilton. - Samuel Seabury wrote four loyalist pamphlets, not one. He wrote them in 1774 and 1775, not in 1776. By 1776, the patriots had already imprisoned Seabury in Connecticut for speaking out against the war. - King George did go mad later in life, although not until many years later. The causes were medical not geopolitical. - Burr’s meeting with General Washington, the meeting in which he tries to offer questions and suggestions, is invented. - John Laurens was not “in South Carolina redefending bravery” during the Battle of Yorktown. He was there at the battle and went to South Carolina later. - Hamilton never asked Burr to join him in writing The Federalist Papers - John Adams didn’t fire Hamilton during his presidency. Hamilton had resigned earlier, in 1795, while Washington was still president. -

Building Stones of the National Mall

The Geological Society of America Field Guide 40 2015 Building stones of the National Mall Richard A. Livingston Materials Science and Engineering Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland 20742, USA Carol A. Grissom Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute, 4210 Silver Hill Road, Suitland, Maryland 20746, USA Emily M. Aloiz John Milner Associates Preservation, 3200 Lee Highway, Arlington, Virginia 22207, USA ABSTRACT This guide accompanies a walking tour of sites where masonry was employed on or near the National Mall in Washington, D.C. It begins with an overview of the geological setting of the city and development of the Mall. Each federal monument or building on the tour is briefly described, followed by information about its exterior stonework. The focus is on masonry buildings of the Smithsonian Institution, which date from 1847 with the inception of construction for the Smithsonian Castle and continue up to completion of the National Museum of the American Indian in 2004. The building stones on the tour are representative of the development of the Ameri can dimension stone industry with respect to geology, quarrying techniques, and style over more than two centuries. Details are provided for locally quarried stones used for the earliest buildings in the capital, including A quia Creek sandstone (U.S. Capitol and Patent Office Building), Seneca Red sandstone (Smithsonian Castle), Cockeysville Marble (Washington Monument), and Piedmont bedrock (lockkeeper's house). Fol lowing improvement in the transportation system, buildings and monuments were constructed with stones from other regions, including Shelburne Marble from Ver mont, Salem Limestone from Indiana, Holston Limestone from Tennessee, Kasota stone from Minnesota, and a variety of granites from several states. -

Positor, Andrés Serafini, Que Es También Mi Marido

Cecilia Figaredo, Andrés Baigorria, Soledad Buss, César Peral, Valeria Celurso, Hernán Nocioni, Yanina Rodolico y Federico Luna, integrantes de Boulevard Tango Foto . Hugo Goñi tango de hoy (Boulevard Tango de Roatta). En la segunda parte, esta vez dos personajes clásicos del tango convertidos en mitos internacionales, Gardel y Piazzolla (de Roatta, el tango escenario coreográfico en movimiento). Reestrenamos en septiembre con una gira por el país. El 4 de septiembre en Rosario, el 7 en Catamarca, el 8 en Santiago del Estero, el 10 en Córdoba, el 12 en San Juan y el 14 de septiembre en Tucumán. ¿Qué anécdota profesional que la haya marcado recuerda? Hay varias, son momentos. Uno, que fue la única vez que bailé con las piernas temblando, que los nervios me hicieron aflojar las piernas, fue cuando bailé en la Ópera de París. Recuerdo el escenario tan inmenso, en la década de 1990, bailábamos La Consagración del Tango con Julio Bocca. Le dije a Julio: “Mirá que me tiemblan un poquito las piernas”. Si bien bailé en el Bolshoi y en otros teatros importantes, no sé por qué cuando bailamos en la Ópera Garnier me desarmó. Después, momen- tos… Saber que en la platea está mirándote Vladimir Vasiliev, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Natalia Makharova que nos vino a ver a Londres. Inolvidable, poder saludar a esa gente, que te digan que te vieron bailar… Yo crecí admirándolos. Si no hubiera sido por ser la compañera de Julio no lo hubiera vivido nunca. Tra- bajar con Marcia Haydée, Carla Fracci, Alessandra Ferri (para mí, ¿Qué mostrará en septiembre? la bailarina de este siglo). -

K. Savage, “The Self-Made Monument: George Washington and the Fight

The Self-Made Monument: George Washington and the Fight to Erect a National Memorial Author(s): Kirk Savage Reviewed work(s): Source: Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 22, No. 4 (Winter, 1987), pp. 225-242 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1181181 . Accessed: 26/01/2012 09:04 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Winterthur Portfolio. http://www.jstor.org The Self-made Monument George Washington and the Fight to Erect a National Memorial Kirk Savage HE 555-FOOT OBELISK on the Mall in Even in his own time Washington and the nation Washington, D.C., is one of the most con- he led were largely products of the collective im- spicuous structures in the world, standing agination. America was then-and to some extent alone on a grassy plain at the very core of national remains-an intangible thing, an idea: a voluntary power-approximately the intersection of the two compact of individuals rather than a family, tribe, great axes defined by the White House and the or race.