Founding Fathers" in American History Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Awakening an Empire of Liberty: Exploring the Roots of Socratic Inquiry and Political Nihilism in American Democracy

Washington University Law Review Volume 83 Issue 2 2005 Awakening an Empire of Liberty: Exploring the Roots of Socratic Inquiry and Political Nihilism in American Democracy Maurice R. Dyson Columbia Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Maurice R. Dyson, Awakening an Empire of Liberty: Exploring the Roots of Socratic Inquiry and Political Nihilism in American Democracy, 83 WASH. U. L. Q. 575 (2005). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_lawreview/vol83/iss2/4 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Law Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AWAKENING AN EMPIRE OF LIBERTY†: EXPLORING THE ROOTS OF SOCRATIC INQUIRY AND POLITICAL NIHILISM IN AMERICAN DEMOCRACY DEMOCRACY MATTERS: WINNING THE FIGHT AGAINST IMPERIALISM. BY CORNEL WEST. PENGUIN PRESS (2004). Pp.229. * Reviewed by Maurice R. Dyson In his latest book, Democracy Matters, Cornel West contends that a perfect storm is in the making, one which has the greatest potential to destroy American democracy. This includes three combined anti- democratic dogmas that have collectively operated to deprive everyday Americans of the ability to critically analyze not only their own state of † The phrase “Empire of Liberty” was first used by Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence. The phrase has come to signify the contradiction of the United States as a beacon of egalitarian freedom and a bulwark of imperialism and racial subordination. -

Political Friendship in Early America

CAMPBELL, THERESA J., Ph.D. Political Friendship in Early America. (2010) Directed by Dr. Robert M. Calhoon. 250 pp. During the turbulent decades that encompassed the transition of the North American colonies into a Republic, America became the setting for a transformation in the context of political friendship. Traditionally the alliances established between elite, white, Protestant males have been most studied. These former studies provide the foundation for this work to examine the inclusion of ―others‖ -- political relationships formed with and by women, persons of diverse ethnicities and races, and numerous religious persuasions -- in political activity. From the outset this analysis demonstrates the establishment of an uniquely American concept of political friendship theory which embraced ideologies and rationalism. Perhaps most importantly, the work presents criteria for determining early American political friendship apart from other relationships. The central key in producing this manuscript was creating and applying the criteria for identifying political alliances. This study incorporates a cross-discipline approach, including philosophy, psychology, literature, religion, and political science with history to hone a conception of political friendship as understood by the Founding Generation. The arguments are supported by case studies drawn from a wide variety of primary documents. The result is a fresh perspective and a new approach for the study of eighteenth century American history. POLITICAL FRIENDSHIP IN EARLY AMERICA by Theresa J. Campbell A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School at The University of North Carolina at Greensboro in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Greensboro 2010 Approved by Robert M. -

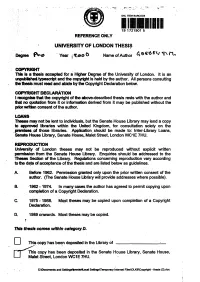

This Thesis Comes Within Category D

* SHL ITEM BARCODE 19 1721901 5 REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year i ^Loo 0 Name of Author COPYRIGHT This Is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London, it is an unpubfished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the .premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962 -1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 -1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. -

Signers of the United States Declaration of Independence Table of Contents

SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE 56 Men Who Risked It All Life, Family, Fortune, Health, Future Compiled by Bob Hampton First Edition - 2014 1 SIGNERS OF THE UNITED STATES DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTON Page Table of Contents………………………………………………………………...………………2 Overview………………………………………………………………………………...………..5 Painting by John Trumbull……………………………………………………………………...7 Summary of Aftermath……………………………………………….………………...……….8 Independence Day Quiz…………………………………………………….……...………...…11 NEW HAMPSHIRE Josiah Bartlett………………………………………………………………………………..…12 William Whipple..........................................................................................................................15 Matthew Thornton……………………………………………………………………...…........18 MASSACHUSETTS Samuel Adams………………………………………………………………………………..…21 John Adams………………………………………………………………………………..……25 John Hancock………………………………………………………………………………..….29 Robert Treat Paine………………………………………………………………………….….32 Elbridge Gerry……………………………………………………………………....…….……35 RHODE ISLAND Stephen Hopkins………………………………………………………………………….…….38 William Ellery……………………………………………………………………………….….41 CONNECTICUT Roger Sherman…………………………………………………………………………..……...45 Samuel Huntington…………………………………………………………………….……….48 William Williams……………………………………………………………………………….51 Oliver Wolcott…………………………………………………………………………….…….54 NEW YORK William Floyd………………………………………………………………………….………..57 Philip Livingston…………………………………………………………………………….….60 Francis Lewis…………………………………………………………………………....…..…..64 Lewis Morris………………………………………………………………………………….…67 -

Argumentative Euphemisms, Political Correctness and Relevance

Argumentative Euphemisms, Political Correctness and Relevance Thèse présentée à la Faculté des lettres et sciences humaines Institut des sciences du langage et de la communication Université de Neuchâtel Pour l'obtention du grade de Docteur ès Lettres Par Andriy Sytnyk Directeur de thèse: Professeur Louis de Saussure, Université de Neuchâtel Rapporteurs: Dr. Christopher Hart, Senior Lecturer, Lancaster University Dr. Steve Oswald, Chargé de cours, Université de Fribourg Dr. Manuel Padilla Cruz, Professeur, Universidad de Sevilla Thèse soutenue le 17 septembre 2014 Université de Neuchâtel 2014 2 Key words: euphemisms, political correctness, taboo, connotations, Relevance Theory, neo-Gricean pragmatics Argumentative Euphemisms, Political Correctness and Relevance Abstract The account presented in the thesis combines insights from relevance-theoretic (Sperber and Wilson 1995) and neo-Gricean (Levinson 2000) pragmatics in arguing that a specific euphemistic effect is derived whenever it is mutually manifest to participants of a communicative exchange that a speaker is trying to be indirect by avoiding some dispreferred saliently unexpressed alternative lexical unit(s). This effect is derived when the indirectness is not conventionally associated with the particular linguistic form-trigger relative to some context of use and, therefore, stands out as marked in discourse. The central theoretical claim of the thesis is that the cognitive processing of utterances containing novel euphemistic/politically correct locutions involves meta-representations of saliently unexpressed dispreferred alternatives, as part of relevance-driven recognition of speaker intentions. It is argued that hearers are “invited” to infer the salient dispreferred alternatives in the process of deriving explicatures of utterances containing lexical units triggering euphemistic/politically correct interpretations. -

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling

Thomas Jefferson and the Ideology of Democratic Schooling James Carpenter (Binghamton University) Abstract I challenge the traditional argument that Jefferson’s educational plans for Virginia were built on mod- ern democratic understandings. While containing some democratic features, especially for the founding decades, Jefferson’s concern was narrowly political, designed to ensure the survival of the new republic. The significance of this piece is to add to the more accurate portrayal of Jefferson’s impact on American institutions. Submit your own response to this article Submit online at democracyeducationjournal.org/home Read responses to this article online http://democracyeducationjournal.org/home/vol21/iss2/5 ew historical figures have undergone as much advocate of public education in the early United States” (p. 280). scrutiny in the last two decades as has Thomas Heslep (1969) has suggested that Jefferson provided “a general Jefferson. His relationship with Sally Hemings, his statement on education in republican, or democratic society” views on Native Americans, his expansionist ideology and his (p. 113), without distinguishing between the two. Others have opted suppressionF of individual liberties are just some of the areas of specifically to connect his ideas to being democratic. Williams Jefferson’s life and thinking that historians and others have reexam- (1967) argued that Jefferson’s impact on our schools is pronounced ined (Finkelman, 1995; Gordon- Reed, 1997; Kaplan, 1998). because “democracy and education are interdependent” and But his views on education have been unchallenged. While his therefore with “education being necessary to its [democracy’s] reputation as a founding father of the American republic has been success, a successful democracy must provide it” (p. -

Jefferson and Franklin

Jefferson and Franklin ITH the exception of Washington and Lincoln, no two men in American history have had more books written about W them or have been more widely discussed than Jefferson and Franklin. This is particularly true of Jefferson, who seems to have succeeded in having not only bitter critics but also admiring friends. In any event, anything that can be contributed to the under- standing of their lives is important; if, however, something is dis- covered that affects them both, it has a twofold significance. It is for this reason that I wish to direct attention to a paragraph in Jefferson's "Anas." As may not be generally understood, the "Anas" were simply notes written by Jefferson contemporaneously with the events de- scribed and revised eighteen years later. For this unfortunate name, the simpler title "Jeffersoniana" might well have been substituted. Curiously enough there is nothing in Jefferson's life which has been more severely criticized than these "Anas." Morse, a great admirer of Jefferson, takes occasion to say: "Most unfortunately for his own good fame, Jefferson allowed himself to be drawn by this feud into the preparation of the famous 'Anas/ His friends have hardly dared to undertake a defense of those terrible records."1 James Truslow Adams, discussing the same subject, remarks that the "Anas" are "unreliable as historical evidence."2 Another biographer, Curtis, states that these notes "will always be a cloud upon his integrity of purpose; and, as is always the case, his spitefulness toward them injured him more than it injured Hamilton or Washington."3 I am not at all in accord with these conclusions. -

3\(Otes on the 'Pennsylvania Revolutionaries of 17J6

3\(otes on the 'Pennsylvania Revolutionaries of 17j6 n comparing the American Revolution to similar upheavals in other societies, few persons today would doubt that the Revolu- I tionary leaders of 1776 possessed remarkable intelligence, cour- age, and effectiveness. Today, as the bicentennial of American inde- pendence approaches, their work is a self-evident monument. But below the top leadership level, there has been little systematic col- lection of biographical information about these leaders. As a result, in the confused welter of interpretations that has developed about the Revolution in Pennsylvania, purportedly these leaders sprung from or were acting against certain ill-defined groups. These sup- posedly important political and economic groups included the "east- ern establishment/' the "Quaker oligarchy/' ''propertyless mechan- ics/' "debtor farmers/' "new men in politics/' and "greedy bankers." Regrettably, historians of this period have tended to employ their own definitions, or lack of definitions, to create social groups and use them in any way they desire.1 The popular view, originating with Charles Lincoln's writings early in this century, has been that "class war between rich and poor, common people and privileged few" existed in Revolutionary Pennsylvania. A similar neo-Marxist view was stated clearly by J. Paul Selsam in his study of the Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776:2 The struggle obviously was based on economic interests. It was a conflict between the merchants, bankers, and commercial groups of the East and the debtor agrarian population of the West; between the property holders and employers and the propertyless mechanics and artisans of Philadelphia. 1 For the purposes of brevity and readability, the footnotes in this paper have been grouped together and kept to a minimum. -

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016

Full List of Book Discussion Kits – September 2016 1776 by David McCullough -(Large Print) Esteemed historian David McCullough details the 12 months of 1776 and shows how outnumbered and supposedly inferior men managed to fight off the world's greatest army. Abraham: A Journey to the Heart of Three Faiths by Bruce Feiler - In this timely and uplifting journey, the bestselling author of Walking the Bible searches for the man at the heart of the world's three monotheistic religions -- and today's deadliest conflicts. Abundance: a novel of Marie Antoinette by Sena Jeter Naslund - Marie Antoinette lived a brief--but astounding--life. She rebelled against the formality and rigid protocol of the court; an outsider who became the target of a revolution that ultimately decided her fate. After This by Alice McDermott - This novel of a middle-class American family, in the middle decades of the twentieth century, captures the social, political, and spiritual upheavals of their changing world. Ahab's Wife, or the Star-Gazer by Sena Jeter Naslund - Inspired by a brief passage in Melville's Moby-Dick, this tale of 19th century America explores the strong-willed woman who loved Captain Ahab. Aindreas the Messenger: Louisville, Ky, 1855 by Gerald McDaniel - Aindreas is a young Irish-Catholic boy living in gaudy, grubby Louisville in 1855, a city where being Irish, Catholic, German or black usually means trouble. The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho - A fable about undauntingly following one's dreams, listening to one's heart, and reading life's omens features dialogue between a boy and an unnamed being. -

Narrative Section of a Successful Application

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/research/scholarly-editions-and-translations-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: The Papers of Thomas Jefferson Institution: Princeton University Project Director: Barbara Bowen Oberg Grant Program: Scholarly Editions and Translations 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 318, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov Statement of Significance and Impact of Project This project is preparing the authoritative edition of the correspondence and papers of Thomas Jefferson. Publication of the first volume of The Papers of Thomas Jefferson in 1950 kindled renewed interest in the nation’s documentary heritage and set new standards for the organization and presentation of historical documents. Its impact has been felt across the humanities, reaching not just scholars of American history, but undergraduate students, high school teachers, journalists, lawyers, and an interested, inquisitive American public. -

University of California

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara The United States and the Barbary Pirates: Adventures in Sexuality, State-Building, and Nationalism, 1784-1815 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Jason Raphael Zeledon Committee in charge: Professor Patricia Cohen, co-chair Professor John Majewski, co-chair Professor Salim Yaqub Professor Mhoze Chikowero June 2016 The dissertation of Jason Raphael Zeledon is approved ______________________________________________ Mhoze Chikowero ______________________________________________ Salim Yaqub ______________________________________________ Patricia Cohen, Committee Co-Chair ______________________________________________ John Majewski, Committee Co-Chair June 2016 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I would like to thank my eleventh-grade American History teacher, Peggy Ormsby. If I had not taken her AP class, my life probably would have gone in a different direction! At that time math was my favorite subject, but her class got me hooked on studying American History. Thanks, too, to the excellent teachers and mentors in graduate school who shaped and challenged my thinking. At American University (where I earned my M.A.), I’d like to thank Max Friedman, Andrew Lewis, Kate Haulman, and Eileen Findlay. I transferred to UCSB to finish my Ph.D. and have thoroughly enjoyed working with Pat Cohen, John Majewski, Salim Yaqub, and Mhoze Chikowero. I’d especially like to thank Pat, who provided insightful feedback on early drafts of my chapter about the Mellimelli mission (which has been published in Diplomatic History). Additionally, I’d like to thank UCSB’s History, Writing, and English Departments for providing Teaching Assistantships and the staffs of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, the Library of Congress Manuscript Reading Room, and the Huntington Library for their help and friendliness. -

American Enlightenment & the Great Awakening

9/9/2019 American Enlightenment & the Great Awakening Explain how & why the movement of a variety of people & ideas across the Atlantic contributed to the development of American culture over time. (Topic 2.7) Enlightenment: Defining the Period 4 Fundamental Principles 1. Lawlike order of the natural world 2. Power of human reason 3. Natural rights of individuals 4. Progressive improvement of society • Natural laws applied to social, political and economic relationships • Could figure out natural laws if they employed reasoning: rationalism 1 9/9/2019 Most Influential • John Locke • Two Treatises of Government: gov’t is bound to follow “natural laws” based on the rights of that people have as humans; sovereignty resides with the people; people have the right to overthrown a government that fails to protect their rights. • Jean-Jacques Rousseau • The Social Contract: Argued that a government should be formed by the consent of the people, who then make their own laws. • Montesquieu • The Spirit of Laws: 3 types of political power – legislative, judicial & executive which each power separated into different branches to protect people’s liberties. Rationale for the American Revolution and the principles of the U.S. Constitution American Enlightenment Start Date/Event 1636: Roger Williams est. R.I. Separation of church & state Freedom of religion Rejects the divine right of kings & supports popular sovereignty 2 9/9/2019 Benjamin Franklin 1732: popularizes the Enlightenment with publication of his almanac Formed clubs for “mutual improvement”