Through the Lens of Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Healthy Ingredients and Traditional Cantonese Cuisine with Unique Taste

2019.12 彩丰小馆 健康的食材,地道的 口味,创意的融合 何志允先生 天津中北假日酒店 Interview with 行政总厨 David He Executive Chef Holiday Inn Tianjin Xiqing CAI FENG XIAO GUAN HEALTHY INGREDIENTS AND TRADITIONAL CANTONESE CUISINE with Unique Taste Follow us on Wechat! InterMediaChina www.tianjinplus.com Enjoy Great Wines, Hand-Crafted Cocktails & Whiskys From Around The World THE CORNER•ACADEMY 考恩预约品鉴店 86 Harbin Rd., Heping District. Tianjin 和平区哈尔滨道86号 T: +86 22 27119871 AN EXQUISITE ITALIAN DINING EXPERIENCE Italian Restaurant & Café Florentia Village Outlet Mall North Qianjin Road Wuquing District, 301700 Tianjin 武清区前进道北侧佛罗伦萨小镇Food-5 Telephone: 022 59698238 www.bellavitaconcept.com Address: Memorable And Personalized Olympic Tower No.104, Chengdu Road Dinning Experience Heping District, Tianjin 和平区成都道126号 THE CORNER•CHANCE 奥林匹克大厦1楼104 考恩餐饮&文化空间 Tel: +86 22 2334 5716 101-102 Harbin Rd., Heping District. Tianjin Opening: 7:00 - 22:00 和平区哈尔滨道102增101号 T: +86 22 83219717 GANG GANG Bread & Wine 冈冈葡萄酒 & 面包店 DELIVERY It's Free over 100RMB! 点餐超过100元免配送费! Delivery can be made everyday Order one day earlier until 14:00am We accept orders by e-mail or Wechat E-mail: [email protected] Wechat: yushengsensen Hi Friends, Another exciting year draws to a close, and the season of celebration, joy and sharing is here. We have prepared this month in our Feature Story Managing Editor a collection of inspiring Christmas dining and celebration experiences Sandy Moore with a series of festive special offers from the most remarkable hotels and [email protected] restaurants in town. Advertising Agency InterMediaChina Tianjin Plus Magazine sincerely wishes you to celebrate the holiday season [email protected] with your family and friends, and enjoy the wonderful events that our partners’ hotels and restaurants have especially prepared for you, and have Publishing Date an unforgettable Christmas and a perfect New Year. -

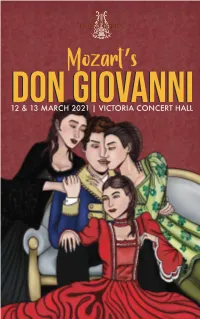

Don Booklet 2021 Low

THE PRIDE WE TAKE IN OFFERING YOU AWARD-WINNING COMFORT That’s what makes us the world’s most awarded airline Best First Class Business Traveller (UK) 2020 Best Airline First Class Business Traveller (Asia Pacific) 2020 Best Airline Premium class DestinAsian Readers’ Choice Awards (Jakarta) 2020 singaporeair.com First performed on 29 October 1797, Prague, Czech Republic Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte Produced by the Singapore Lyric Opera Artists’ Training Programme Initiated by the Artistic Director Nancy Yuen in 2016, this performance-based artists' training programme supports the artistic development of talented young singers and provides opportunities for them to hone their skills and gain experience on the professional stage in Singapore. They have access to coaching in languages, stagecraft and vocal techniques, and weekly rehearsals on popular operatic excerpts chosen by the Artistic Committee, and access to master classes by visiting artists. To date, members of the ATP have appeared on the main stage of the Esplanade Theatre and Victoria Concert Hall as well as performing in many educational outreach programmes as soloists and as members of the ensemble, bringing opera excerpts and songs to unconventional places like the National Library, Esplanade Concourse, Our Tampines Hub amongst others. The singers receive regular coachings by Nancy Yuen and Jessica Chen with assistance from répétiteur Aloysius Foong. In 2019, they performed a 90 minutes Abridged Version of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro at the Victoria Concert Hall to much critical acclaim. Sung in Italian with English and Chinese surtitles An approximately 90 minutes Abridged Version with no intermission. Late-comers will only be admitted at suitable breaks. -

Primo Valerio Alfieri

Curriculum Vitae VALERIO ALFIERI INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI PRIMO VALERIO ALFIERI via Tresanti 130,montespertoli 50025 Firenze 328 3731418 [email protected] http://www.valerio-alfieri.it Sostituire con servizio di messaggistica istantanea Sostituire con account di messaggistica Sesso M | Data di nascita 06/03/1959 | Nazionalità ITALIANA OCCUPAZIONE PER LA QUALE SI CONCORRE POSIZIONE RICOPERTA OCCUPAZIONE DESIDERATA LIGHT DESIGNER TITOLO DI STUDIO DICHIARAZIONI PERSONALI ESPERIENZA PROFESSIONALE 40 ANNI DI LAVORO (vedi http://WWW.valerio-alfieri.it) [Inserire separatamente le esperienze professionali svolte iniziando dalla più recente.] Sostituire con date LIGHT DESIGNER (da - a) Dal 1981 al 1987, e` responsabile con qualifica di capo elettricista del TEATRO REGIONALE TOSCANO, in sede e nei vari teatri italiani toccati dalle tournée. In questi anni lavora per tutti gli spettacoli di Luca Ronconi prodotti dall’Ente e con altri registi come Franco Zeffirelli, Roberto de Simone , Roberto Guicciardini, Antoine Vitez, Franco Branciaroli... Nel 1987, fonda con quattro colleghi la “F.LLI EDISON”, società di servizi tecnici per lo spettacolo e la moda nella quale rimane sino al 1988 Il successo della società si basava, e si basa tuttora, sull’esperienza tecnico/creativa dei soci per la realizzazione di impianti di illuminotecnica nell’ambito del teatro, moda e pubblicità. Durante questo periodo è Direttore Tecnico per le sfilate di: Armani /Gianfranco Ferre’ /Donna Karen / Costume National /Dolce e Gabbana /Moschino / Hugo Boss... 1988 Light Designer del Festival di Montepulciano. Operatore al computer per la rassegna Festival dei due Mondi di Spoleto -Teatro Nuovo. 1989 Light Designer del Festival di Montalcino. 1990, gestisce a seconda dei casi, come creatore luci o responsabile tecnico, le produzioni del Teatro Stabile di Bolzano in sede e nelle tournée di compagnia. -

New Tou Ri G Ctions Produ

International Centre for Theatrical new Creations (C.I.C.T.) a�d 2019 season 2018 tou ri�g ctions Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord produ �i�g forthco 2018 uctions 2019 prod love �e de te� r Simon Gosselin Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, that already produced Based on the stories by The Second Woman (2011), Mimi, Scènes de la vie Raymond Carver de Bohème (2014) and presented The Night is falling... Adaptation and direction and RDV Gare de l’Est in 2013, welcomes again Guillaume Vincent for a new production. Guillaume Vincent Playwriting Carver is often called the American Chekhov. Except, with Carver, litres of Gin replace the samovar. Marion Stoufflet As in Chekhov, the drama is not played out in words, Sets but also in the silences, things unspoken. Which explains James Brandily the strange impression that there is no drama, at least Lighting in the appearance. His favourite theme: the couple. He portrays it in its fragile moments, when despite Niko Joubert appearances the malaise seeps in like a poison. Costumes In this staging of Love me tender the actor holds the Lucie Ben Bâta central place. Six stories have been adapted for eight With performers, each of whom plays two parts, each having Emilie Incerti Formentini to tune in, as in music and despite the disagreements Victoire Goupil of their characters, to two, to four, to eight. Florence Janas Guillaume Vincent Stefan Konarske Production C.I.C.T.– Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord; Cie MidiMinuit Cyril Metzger With the artistic participation of Jeune Théâtre National and Ecole du Nord Alexandre -

Gabriele Ribis Baritono, Regista, Direttore Artistico

Gabriele Ribis Baritono, Regista, Direttore artistico INFORMAZIONI DI Email: [email protected] CONTATTO Indirizzo: Località Visogliano / Vižovlje 14/V - 34011 Duino Aurisina / Devin-Nabrež ina (TS) Telefono: +390402039846 Data di nascita : 18-07-1973 Nazionalità : Italiana Link : www.gabrieleribis.com DESCRIZIONE Baritono dalla carriera internazionale, regista, direttore artistico; esperto nella creazione di progetti artistici originali in grado di abbinare Turismo e Cultura. ESPERIENZA Gorizia, Italia Direttore artistico Dicembre 2007 - Attuale Piccolo Opera Festival del Friuli Venezia Giulia Fondatore -Direttore artistico dalla prima edizione -Sviluppo del progetto artistico e inserimento nel mercato del turismo musicale europeo -Accesso ai nanziamenti triennali della Regione Autonoma Friuli Venezia Giulia -Proiezione transfrontaliera (Italia-Slovenia) -Cooperazione internazionale Gerusalemme, Israele Direttore artistico Novembre 2012 - Attuale The Jerusalem Opera Direzione artistica - Consulenza produzione e comunicazione -Ideazione prima produzione completa in sito storico -Riconoscimento compagnia da parte dello Stato d'Israele -Residenza presso Jerusalem Theatre -Collaborazione con Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra Trieste, Italia Direttore artistico Ottobre 2019 - Attuale Karsiart Rebranding manifestazione -Ideazione programma -Individuazione nuove locations -assistenza compilazione bandi nanziamento -Sviluppo progetto in coordinamento con oerta turistica - Consulenza globale di gestione (produzione, tecnica e comunicazione) Gerusalemme, -

An Exceptional MAD Performance at IST MAD夜晚,感受不一样的IST

2015.05 16 An Exceptional MAD Performance at IST MAD夜晚,感受不一样的IST InterMediaChina www.tianjinplus.com IST offers your children a welcoming, inclusive international school experience, where skilled and committed teachers deliver an outstanding IB education in an environment of quality learning resources and world-class facilities. IST is... fully accredited by the Council of International Schools (CIS) IST is... fully authorized as an International Baccalaureate World School (IB) IST is... fully accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) IST is... a full member of the following China and Asia wide international school associations: ACAMIS, ISAC, ISCOT and EARCOS Website: www.istianjin.org Email: [email protected] Tel: 86 22 2859 2003/5/6 NO.22 Weishan South Road, Shuanggang, Jinnan District, Tianjin 300350, P.R.China Freelance Writers, Editors & Proofreaders Needed at Tianjin’s Premier Lifestyle Magazine! We are looking for: · Native or high level English speakers who also have excellent writing skills. · A good communicator who has the ability to work as part of a diverse and dynamic team. Advertising Agency InterMediaChina · Basic Chinese language abilities advertising@tianjinplus. com and experience in journalism and/or Publishing Date editing are preferred but not crucial. May 2015 If you are interested in contributing Tianjin Plus is a Lifestyle Magazine. to our magazine, please send your For Members ONLY CV and a brief covering letter to www. tianjinplus. com [email protected] ISSN 2076-3743 -

Programme Calendar

REVISED AND UPDATED PROGRAMME CALENDAR REVISED AND UPDATED CHRISTIAN SPIRIT SEASON A BRIEF HISTORY Beginning the 136th Opera Season OF OPERA IN HUNGARY “EVEN THE ATHEISTS ARE CHRISTIAN IN EUROPE!” This statement has never before been used as the title for opening an opera season. But now, there it is. 2019 Former Prime Minister József Antall’s words give an exact summary of everything that is the essence of a common European culture. When we announce Christian Spirit Season, we are driven not by religious or devout fervour, nor do It has been more than 200 years since the publication of the play that was later to be used as the we intend to discriminate against anyone with any different beliefs. We merely want to share the experience that the new, libretto of the first surviving Hungarian musical drama. And even though some form of opera perfor- Christian man was born from the values of ancient Greece and Rome, and from the history and the books of Judaism. mance had already existed in Hungary in the courts of the aristocrats and primates – for an example, Over the course of history, this new man became not only Christian, but also European. And the works composed over the course of thousands of years are a heritage worth protecting. But how can we protect it if we are unable to even identify it? one need look no further than Haydn, who worked at Eszterháza (today’s Fertőd) – the first institu- tion at the national level was the one which opened as the Hungarian Theatre of Pest in 1837 and was Whatever happens, the community with other European nations founded on the solid ground of Christianity is unde- renamed the National Theatre in 1840. -

Kvadrat-In-Use-Uk-Web.Pdf

3 Kvadrat in use We are Kvadrat Kvadrat has been leading the field in textile innovation since 1968 when our company was founded. We produce contemporary high-quality textiles and textile-related products for architects, designers and private consumers to specify in public spaces and domestic interiors. We are a progressive design company, constantly exploring the boundaries of textile design and the creative application of our products in a diverse range of areas. Originating in the small town of Ebeltoft in Denmark, Kvadrat has deep roots in Scandinavia’s design tradition. Our long heritage is a constant source of inspiration to us, although today we are a cosmopolitan company with a global perspective and a worldwide clientele. Brand breakdown Kvadrat is, in fact, five very different specialist brands: Kvadrat produces That is why we manufacture the majority of our woollen fabrics in high-quality upholstery, curtains and textile-related products; Kvadrat/ England and our Trevira CS products in the Netherlands, where the Raf Simons offers exclusive textiles and accessories for the home; abilities of local craftsmen are proven and where we are able to Kvadrat Soft Cells makes engineered acoustic panels; Danskina produces achieve the high quality we demand. premium rugs; and Kinnasand supplies first-class curtains and rugs for contemporary homes. Our high-quality textiles are technologically superior and made to last. They come with a 10-year warranty and comply with all the With our different product lines you can create tactile, comfortable and relevant legislation, regulations and standards. productive spaces that fit any design scheme: upholsteries for furniture, curtains and roller blinds to decorate the windows, acoustic panels for wall and ceiling as well as rugs for floors. -

THROUGH the LENS of TIME Richter | Brotons | Schnittke | Yun David Fung, Piano City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra | Carlos Izcaray

Francisco Fullana THROUGH THE LENS OF TIME Richter | Brotons | Schnittke | Yun David Fung, piano City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra | Carlos Izcaray ORC100080 THROUGH THE LENS OF TIME Max Richter (b.1966) The Four Seasons Recomposed (2012) – Spring 1. I 2.42 Salvador Brotons (b.1959) 2. II 4.01 16. Variacions sobre un tema barroc for solo violin 6.02 3. III 3.18 (World premiere recording) Isang Yun (1917-1995) Max Richter 4. Königliches Thema for solo violin 7.43 The Four Seasons Recomposed (2012) – Winter 17. I 3.04 Max Richter 18. II 2.48 The Four Seasons Recomposed (2012) – Summer 19. III 5.12 5. I 4.07 6. II 4.23 Total time 73.21 7. III 3.37 Francisco Fullana, violin Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998) * David Fung, piano Suite in the Old Style for violin and piano* City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra 8. I Pastorale 3.25 Carlos Izcaray 9. II Ballett 2.25 10. III Menuett 2.52 11. IV Fuge 2.46 12. V Pantomime 3.28 Max Richter The Four Seasons Recomposed (2012) – Autumn 13. I 6.18 14. II 3.23 15. III 1.41 2 3 I invite you to join me on a musical journey that stands at the crossroads between musical paths. Through the Lens of Time brings together four modern perspectives reimagining the Baroque tradition: a dialogue between Old and New that prompts both composers and performers to explore music from giants of the past and its place in their own lives. Vivaldi and Bach’s melodies inspired by Chris Potter’s saxophone and the twelve-tone system; from the Roman Pantomime to Soviet cartoons, are you ready to come on a musical adventure through the centuries? Francisco 4 5 Through the Lens of Time After learning and understanding Yun’s devilish work, I started performing it Life is full of coincidences, seemingly meaningless and isolated events that on their alongside Bach’s Chaconne during the 15/16 season. -

Tianjin Reviews, Events and Information TIANJIN FOOD and DRINK AWARDS the City's Best Bars and Restaurants Revealed See P2

tj Tianjin reviews, events and information TIANJIN FOOD AND DRINK AWARDS The City's Best Bars and Restaurants Revealed See p2 THE BUZZ TRANSPORT BLAST FROM THE PAST Damaged vehicles from last August’s Port of Tianjin warehouse explosion are finding their way onto the black market – and into unsuspecting hands. In an incident reported last month, a buyer paid RMB625,000 for a ‘brand new’ Jeep Grand Cherokee only to discover that it was a refurbished vehicle that had been damaged in the explosion. According to a notice released by Jeep last December, its Jeep Grand Cherokees were in the open-air – although outside the blast radius – at the time of the event. As such, the company requires its dealers to inform customers of this before purchasing. Additionally, 1,300 severely damaged vehicles were given to an insurance company, which was directed to keep them. Since then, a black market of dealers and repair shops has been repairing the cars and selling them at reduced prices. A professor at the China University of Political Science and Law, Zhu Wei, told China Radio International that industry regulators need to “ensure the cars that are meant to be destroyed are indeed destroyed.” RANDOM NUMBER EDUCATION ROMANCE 101 Tianjin University is now offering classes in an unconventional – yet universally experienced – subject regarding matters of the heart. The course, titled ‘Basic Theory and Experience of Love' has proved popular, with around 200 students attending the first lecture. Topics covered range from dating tips and etiquette to counseling, and are taught by teachers from the university and external experts. -

Mozart's Don Giovanni Programme Booklet LOW

THE PRIDE WE TAKE IN OFFERING YOU AWARD-WINNING COMFORT That’s what makes us the world’s most awarded airline Best First Class Business Traveller (UK) 2020 Best Airline First Class Business Traveller (Asia Pacific) 2020 Best Airline Premium class DestinAsian Readers’ Choice Awards (Jakarta) 2020 singaporeair.com First performed on 29 October 1797, Prague, Czech Republic Libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte Produced by the Singapore Lyric Opera Artists’ Training Programme Initiated by the Artistic Director Nancy Yuen in 2016, this performance-based artists' training programme supports the artistic development of talented young singers and provides opportunities for them to hone their skills and gain experience on the professional stage in Singapore. They have access to coaching in languages, stagecraft and vocal techniques, and weekly rehearsals on popular operatic excerpts chosen by the Artistic Committee, and access to master classes by visiting artists. To date, members of the ATP have appeared on the main stage of the Esplanade Theatre and Victoria Concert Hall as well as performing in many educational outreach programmes as soloists and as members of the ensemble, bringing opera excerpts and songs to unconventional places like the National Library, Esplanade Concourse, Our Tampines Hub amongst others. The singers receive regular coachings by Nancy Yuen and Jessica Chen with assistance from répétiteur Aloysius Foong. In 2019, they performed a 90 minutes Abridged Version of Mozart’s Le Nozze di Figaro at the Victoria Concert Hall to much critical acclaim. Sung in Italian with English and Chinese surtitles An approximately 90 minutes Abridged Version with no intermission. Late-comers will only be admitted at suitable breaks. -

1. Abo, 17.10.2019

MÜNCHENER KAMMERORCHESTER WÄRME — 1. ABO, 17.10.2019 Oskar-von-Miller-Ring 1, 80333 München Telefon 089.46 13 64 -0, Fax 089.46 13 64 -11 www.m-k-o.eu ECT-Ugur.pdf 1 10/1/19 22:45 IT SPEAKS VOLUMES ABOUT A COMPANY that its colleagues bond together over cultural pursuits like classical music, rather than just drinking beer (although, we do this too, it is Munich after all…). Through ECT I got to know the MKO, which exposed me to more modern music. But that’s not all Munich and ECT have exposed me to. Living and working here offers me the best of both worlds: I get C to do my life’s most meaningful work, while having the thrill of M adventure that comes with discovering a new place. And now, Y Munich and ECT are home for me. CM MY CY CMY K UĞUR TURKEY www.ect-telecoms.com Ich habe bei Menschen nie an Kälte geglaubt. An Verkrampfung schon, aber nicht an Kälte. Das Wesen des Lebens ist Wärme. Selbst Hass ist gegen ihre natürliche Richtung gekehrte Wärme. Peter Høeg, Fräulein Smillas Gespür für Schnee 1. ABONNEMENTKONZERT Donnerstag, 17. Oktober 2019, 20 Uhr, Prinzregententheater ALEXANDER MELNIKOV KLAVIER CLEMENS SCHULDT DIRIGENT JEAN-FÉRY REBEL (1666–1747) ›Le Cahos‹ aus ›Les Éléments‹ JUSTE˙ JANULYTE˙ (*1982) ›Elongation of Nights‹ CLARA SCHUMANN (1819–1896) Konzert für Klavier und Orchester a-Moll op.7 Allegro maestoso Romance: Andante non troppo con grazia Allegro non troppo Pause Das Konzert wird am 24. Oktober 2019 ab 20.05 Uhr im Programm BR-Klassik gesendet.