"Leads," for Instance, Looks at Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcast Journalism Course Descriptions and Career Recommendations

Broadcast Journalism Course Descriptions and Career Recommendations JOUR 402 Broadcast Reporting The class will focus on writing and reporting well-balanced, comprehensive and visually compelling stories. Undergraduate and graduate students research, report, write, shoot and edit stories. During TV day-of-air shifts in the Annenberg Media Center, students learn how to meet the same deadlines that professional reporters handle in small, medium and large markets. They also put together feature packages and could get the chance to do live shots for the nightly newscasts. This class is a MUST for any student who wants to be a TV reporter in news, sports or entertainment. It is also strongly recommended for students who want to learn how to field produce packages. JOUR 403 Television News Production Students sharpen news judgment and leadership skills by producing live day-of-air television newscasts, creating digital content, and using social media. They make decisions about news coverage, stories and presentation while managing reporters, anchors, writers, editors and many others under deadline pressure. JOUR 403 producers will write, copy edit and supervise live shots. Students have used skills learned in JOUR 403 to excel in jobs including local news producing, news reporting, sports producing and network segment producing. This class is a MUST for any student who wants to be the producer of a TV newscast or other type of live program. It is STRONGLY recommended for students who want to be TV news producers and reporters, sports producers or local/network segment producers. JOUR 405 Non-Fiction Television This class introduces students to the process of producing a documentary for digital and broadcast platforms. -

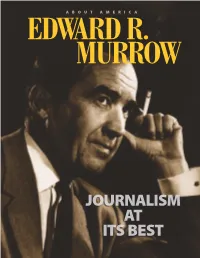

Edward R. Murrow

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life.............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S.....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy ..........................................................................16 Bibliography..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: University of Maryland; right, Digital Front cover: © CBS News Archive Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. Tufts University. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; 5 : left, North Wind Picture Archives; bottom, AP/WWP. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Executive Editor: George Clack 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao and Archives, Tufts University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Chandley McDonald University. Photo Research: Ann Monroe Jacobs 11: left, Library of American Broadcasting, Reference Specialist: Anita N. Green 1 EDWARD R. MURROW: A LIFE By MARK BETKA n a cool September evening somewhere Oin America in 1940, a family gathers around a vacuum- tube radio. As someone adjusts the tuning knob, a distinct and serious voice cuts through the airwaves: “This … is London.” And so begins a riveting first- hand account of the infamous “London Blitz,” the wholesale bombing of that city by the German air force in World War II. -

TV Journalism & Programme Formats

Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping TV Journalism & Programme Formats TV Journalism & Programme Formats SEMESTER 3 Study Material for Students 1 Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping TV Journalism & Programme Formats CAREER OPPORTUNITIES IN MEDIA WORLD Mass communication and Journalism is institutionalized and source specific. It functions through well-organized professionals and has an ever increasing interlace. Mass media has a global availability and it has converted the whole world in to a global village. A qualified journalism professional can take up a job of educating, entertaining, informing, persuading, interpreting, and guiding. Working in print media offers the opportunities to be a news reporter, news presenter, an editor, a feature writer, a photojournalist, etc. Electronic media offers great opportunities of being a news reporter, news editor, newsreader, programme host, interviewer, cameraman, producer, director, etc. Other titles of Mass Communication and Journalism professionals are script writer, production assistant, technical director, floor manager, lighting director, scenic director, coordinator, creative director, advertiser, media planner, media consultant, public relation officer, counselor, front office executive, event manager and others. 2 Edited with the trial version of Foxit Advanced PDF Editor To remove this notice, visit: www.foxitsoftware.com/shopping TV Journalism & Programme Formats INTRODUCTION The book deals with Television for journalism and Writing for visuals. Student will understand the medium f r o m Piece to Camera. The book will tell students about Presentation, Reporting, Interview, Reportage, Live Shows and Anchoring a Show. -

Edward R. Murrow: Journalism at Its Best

ABOUT AMERICA EDWARD R. MURROW JOURNALISM AT ITS BEST TABLE OF CONTENTS Edward R. Murrow: A Life .............................................................1 Freedom’s Watchdog: The Press in the U.S. ....................................4 Murrow: Founder of American Broadcast Journalism ....................7 Harnessing “New” Media for Quality Reporting .........................10 “See It Now”: Murrow vs. McCarthy ...........................................13 Murrow’s Legacy...........................................................................16 Bibliography ..................................................................................17 Photo Credits: 12: Joe Barrentine, AP/WWP. Front cover: © CBS News Archive 13: Digital Collections and Archives, Page 1: CBS, Inc., AP/WWP. Tufts University. 2: top left & right, Digital Collections and Archives, 14: top, Time Life Pictures/Getty Images; Tufts University; bottom, AP/WWP. bot tom, AP/ W WP. 4: Louis Lanzano, AP/WWP. Back cover: Edward Murrow © 1994 United States 5: left, North Wind Picture Archives; Postal Service. All Rights Reserved. right, Tim Roske, AP/WWP. Used with Permission. 7: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. 8: top left, U.S. Information Agency, AP/WWP; right, AP/WWP; bottom left, Digital Collections Executive Editor: George Clack and Archives, Tufts University. Managing Editor: Mildred Solá Neely 10: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts Art Director/Design: Min-Chih Yao University. Contributing editors: Chris Larson, 11: left, Library of American -

20Entrepreneurial Journalism

Journalism: New Challenges Karen Fowler-Watt and Stuart Allan (eds) Journalism: New Challenges Edited by: Karen Fowler-Watt and Stuart Allan Published by: Centre for Journalism & Communication Research Bournemouth University BIC Subject Classification Codes: GTC Communication Studies JFD Media Studies KNTD Radio and television industry KNTJ Press and journalism JNM Higher and further education, tertiary education First published 2013, this version 1.02 ISBN: 978-1-910042-01-4 [paperback] ISBN: 978-1-910042-00-7 [ebook-PDF] ISBN: 978-1-910042-02-1 [ebook-epub] http://microsites.bournemouth.ac.uk/cjcr/ Copyright © 2013 Acknowledgements Our first thank you is to the contributors who made Journalism: New Challenges possible, not least for so generously sharing their expertise, insights and enthusiasm for this approach to academic e-publishing. This endeavour was supported by the Centre for Journalism and Communication Research (CJCR), here in the Media School at Bournemouth University, UK. With regard to the production and distribution of this book, we are grateful to Einar Thorsen and Ann Luce for their stellar efforts. They would like to thank, in turn, Carrie Ka Mok for setting its design and layout, and Ana Alania for contributing ideas for the cover. Many thanks as well to Mary Evans, Emma Scattergood and Chindu Sreedharan for their helpful sugges- tions on how to develop this publishing venture. Karen Fowler-Watt and Stuart Allan, editors Table of contents Introduction i Karen Fowler-Watt and Stuart Allan Section One: New Directions -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE SELF-PERCEPTION OF VIDEO GAME JOURNALISM: INTERVIEWS WITH GAMES WRITERS REGARDING THE STATE OF THE PROFESSION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Severin Justin Poirot Norman, Oklahoma 2019 THE SELF-PERCEPTION OF VIDEO GAME JOURNALISM: INTERVIEWS WITH GAMES WRITERS REGARDING THE STATE OF THE PROFESSION A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE GAYLORD COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION BY Dr. David Craig, Chair Dr. Eric Kramer Dr. Jill Edy Dr. Ralph Beliveau Dr. Julie Jones © Copyright by SEVERIN JUSTIN POIROT 2019 All Rights Reserved. iv Acknowledgments I’ve spent a lot of time and hand wringing wondering what I was going to say here and whom I was going to thank. First of all I’d like to thank my committee chair Dr. David Craig. Without his guidance, patience and prayers for my well-being I don’t know where I would be today. I’d like to also thank my other committee members: Dr. Eric Kramer, Dr. Julie Jones, Dr. Jill Edy, and Dr. Ralph Beliveau. I would also like to thank former member Dr. Namkee Park for making me feel normal for researching video games. Second I’d like to thank my colleagues at the University of Oklahoma who were there in the trenches with me for years: Phil Todd, David Ferman, Kenna Griffin, Anna Klueva, Christal Johnson, Jared Schroeder, Chad Nye, Katie Eaves, Erich Sommerfeldt, Aimei Yang, Josh Bentley, Tara Buehner, Yousuf Mohammad and Nur Uysal. I also want to extend a special thanks to Bryan Carr, who possibly is a bigger nerd than me and a great help to me in finishing this study. -

Journalism (JOUR) 1

Journalism (JOUR) 1 JOUR 2712. Intermediate Print Reporting. (4 Credits) JOURNALISM (JOUR) This is an intermediate reporting course which focuses on developing investigative skills through the use of human sources and computer- JOUR 1701. Introduction to Multimedia Journalism With Lab. (4 Credits) assisted reporting. Students will develop beat reporting skills, source- A course designed to introduce the student to various fundamentals building and journalism ethics. Students will gather and report on actual of journalism today, including writing leads; finding and interviewing news events in New York City. Four-credit courses that meet for 150 sources; document, database and digital research; and story minutes per week require three additional hours of class preparation per development and packaging. The course also discusses the intersection week on the part of the student in lieu of an additional hour of formal of journalism with broader social contexts and questions, exploring the instruction. changing nature of news, the shifting social role of the press and the Attribute: JWRI. evolving ethical and legal issues affecting the field. The course requires a JOUR 2714. Radio and Audio Reporting. (4 Credits) once weekly tools lab, which introduces essential photo, audio, and video A survey of the historical styles, formats and genres that have been used editing software for digital and multimedia work. This class is approved for radio, comparing these to contemporary formats used for commercial to count as an EP1 seminar for first-year students; students need to and noncommercial stations, analyzing the effects that technological, contact their class dean to have the attribute applied. Note: Credit will not social and regulatory changes have had on the medium. -

Edward R. Murrow at the National Press Club, May 24, 1961

Edward R. Murrow at the National Press Club, May 24, 1961 President John F. Kennedy with Director of USIA, Edward R. Murrow, March 21, 1961. Cecil Stoughton. White House Photographs. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. Digital Id.: JFKWHP-ST-C61-1-61 Famed broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow (1908-1965) chose the National Press Club as the forum for his first speech since taking office a few months earlier as director of the United States Information Agency (USIA), the organization responsible for communicating U.S. policy abroad and carrying out much of the government’s international information and cultural programs. Created in 1953 as an independent agency reporting directly to the president, USIA took over from the State Department the operation of Voice of America (VOA) radio broadcasts and U.S. Information Service (USIS) centers around the world, programs that had been established during World War II to communicate U.S. war aims and otherwise aid in the war effort abroad. Following the war, State Department officials, skeptical of the diplomatic value of programs they considered “propaganda,” persuaded Congress to cut VOA and USIS allocations severely. In late 1947, however, a committee of U.S. senators traveling in Europe reported “a campaign of vilification and misrepresentation” conducted by the Soviet Union’s newly formed propaganda agency Cominform to discredit the Marshall Plan recently implemented to rebuild Europe with massive amounts of U.S. aid. 1 Congress subsequently passed the Smith-Mundt Act—with the Senate voting unanimously in its favor—to establish a permanent peacetime program “to promote the better understanding of the United States among the peoples of the world and to strengthen cooperative international relations.” President Harry S. -

Journalism and Mass Communication

www.kent.edu/jmc JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION Today’s fast-changing media marketplace demands professionals who can hit the ground running. The School of Journalism and Mass Communication’s nationally accredited program prepares students to not only succeed in this marketplace but also innovate, manage and lead. Our hands-on curriculum puts students at the cutting edge of today’s emerging multimedia careers, building a strong foundation Journalism (MULTIMEDIA NEws) Multimedia journalism majors train in all aspects of writing, editing, of communication skills and an entrepreneurial mindset. We offer a layout and design of newspapers. Students work for the The Kent Stater full range of programs in journalism, public relations, advertising and for at least one semester as part of a reporting class, and many continue electronic media, leveraging a state-of–the-art facility in Franklin Hall their involvement beyond that course. Most graduates find employment and a faculty with in-depth experience in their fields. The curriculum at daily or weekly print and online newspapers. also allows students to earn a liberal education with additional coursework across our comprehensive university. To learn and practice those core multimedia, multiplatform skills Journalism (PHotojournalism) Photojournalism majors study the visual reporting of news, reporting and techniques, our Franklin Hall facility is second to none, from the and storytelling. This major is for students who have good visual converged newsroom to the digital high-definition television studio perception and want to demonstrate this skill through photography. A to fully equipped multimedia learning laboratories. dynamic portfolio is needed to break into this career, and the courses As part of coursework in all majors, students must complete pro- are geared toward producing one. -

Digital Journalism Studies the Key Concepts

Digital Journalism Studies The Key Concepts FRANKLIN, Bob and CANTER, Lily <http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5708-2420> Available from Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/26994/ This document is the author deposited version. You are advised to consult the publisher's version if you wish to cite from it. Published version FRANKLIN, Bob and CANTER, Lily (2019). Digital Journalism Studies The Key Concepts. Routledge key guides . Routledge. Copyright and re-use policy See http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive http://shura.shu.ac.uk <BOOK-PART><BOOK-PART-META><TITLE>The key concepts</TITLE></BOOK- PART-META></BOOK-PART> <BOOK-PART><BOOK-PART-META><TITLE>Actants</TITLE></BOOK-PART- META> <BODY>In a special issue of the journal Digital Journalism, focused on reconceptualizsing key theoretical changes reflecting the development of Digital Journalism Studies, Seth Lewis and Oscar Westlund seek to clarify the role of what they term the “four A’s” – namely the human actors, non-human technological actants, audiences and the involvement of all three groups in the activities of news production (Lewis and Westlund, 2014). Like Primo and Zago, Lewis and Westlund argue that innovations in computational software require scholars of digital journalism to interrogate not simply who but what is involved in news production and to establish how non-human actants are disrupting established journalism practices (Primo and Zago, 2015: 38). The examples of technological actants -

Journalism and Broadcasting

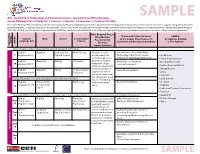

SAMPLE Arts, Audio/Video Technology and Communications: Journalism and Broadcasting Career Pathway Plan of Study for Learners Parents Counselors Teachers/Faculty This Career Pathway Plan of Study (based on the Journalism and Broadcasting Pathway of the Arts, Audio/Video Technology and Communications Career Cluster) can serve as a guide, along with other career planning materials, as learners continue on a career path. Courses listed within this plan are only recommended coursework and should be individualized to meet each learner’s educational and career goals. *This Plan of Study, used for learners at an educational institution, should be customized with course titles and appropriate high school graduation requirements as well as college entrance requirements. Other Required Courses Other Electives *Career and Technical Courses SAMPLE English/ Math Science Social Studies/ Recommended and/or Degree Major Courses for Occupations Relating Language Arts Sciences Journalism and Broadcasting Pathway to This Pathway LEVELS GRADE Electives EDUCATION Learner Activities Interest Inventory Administered and Plan of Study Initiated for all Learners English/ Algebra I Earth or Life or World History All plans of study • Introduction to Arts, Audio/Video 9 Language Arts I Physical Science should meet local Technology and Communications Art Director and state high school • Information Technology Applications Audio-Video Operator graduation require- English/ Geometry Biology U.S. History • Media Arts Fundamentals Broadcast Technician 10 Language Arts -

Broadcast Journalism Courses Cr Sem

GRAMBLING STATE UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MASS COMMUNICATION COLLEGE OF PROFESSIONAL Name _______________________________________ Advisor ______________________________________ Address _______________________________________ Major ________________________________________ (Home) Address ______________________________________ Minor ________________________________________ (Local) G # ______________________ Date Admitted To Program: ______________________ GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS FOR THE B.A. DEGREE IN MASS COMMUNICATION Broadcast Journalism Courses Cr Sem. Grade Courses Cr Sem Grade Hrs Taken Hrs. Taken FRESHMAN SEMINAR 2 THE SOCIAL SCIENCES 3 FYE 101 First Year Experience 1 SOC 101 Introduction to Social Science 3 FYE 102 First Year Experience 1 ENGLISH 6 ECONOMICS 3 ENG 101 Freshman Composition 3 ECON 201 Macroeconomics 3 ENG 102 Freshman Composition 3 Fine and Performing Arts 3 ENGLISH Literature 3 ART 210 Intro. to Fine & Performing Arts 3 ENG 200 English literature 3 MATHEMATICS 6 MATH 147 Pre-calculus I 3 MATH 148 Pre-calculus II 3 FOREIGN LANGUAGES 6 (Students are to take all 6 hours in one language) THE NATURAL SCIENCES 10 BIOL 103 Prin. of Biology 3 BIOL 104 Prin. of Biology 3 Cognate (Required) 18 BIOL 105 Lab (Non-Majors) 1 PS 201 American National Government 3 SCI 105 Physical Science Survey I 3 ENG 213 Advanced Composition 3 ENG 310 Advanced Grammar 3 SOC 201 Introduction to Sociology 3 ST 212 Fundamentals of Public Speaking 3 HISTORY 6 PSY 200 Introduction to Psychology 3 HIST 101 History of West. Civilization 3 HIST 104 Modern World History 3 Electives (Two Courses) 6 C.S.107 Computers & Society 3 MUS 219 Music Appreciation 3 REQUIRED EXAMINATIONS PHIL 201 Intro to Philosophy 3 GET 300 Rising Junior Examination 0 SOC 203 Social Problems 3 ST 208 Speech Arts 3 HUM 200 African Culture 3 HUM 202 Non-Western Culture 3 SCI 106 Physical Science Survey II 3 The above General Education requirements have been explained to me and I agree to comply with them.