Pakistan Conflict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema

Movie Aquisitions in 2010 - Hindi Cinema CISCA thanks Professor Nirmal Kumar of Sri Venkateshwara Collega and Meghnath Bhattacharya of AKHRA Ranchi for great assistance in bringing the films to Aarhus. For questions regarding these acquisitions please contact CISCA at [email protected] (Listed by title) Aamir Aandhi Directed by Rajkumar Gupta Directed by Gulzar Produced by Ronnie Screwvala Produced by J. Om Prakash, Gulzar 2008 1975 UTV Spotboy Motion Pictures Filmyug PVT Ltd. Aar Paar Chak De India Directed and produced by Guru Dutt Directed by Shimit Amin 1954 Produced by Aditya Chopra/Yash Chopra Guru Dutt Production 2007 Yash Raj Films Amar Akbar Anthony Anwar Directed and produced by Manmohan Desai Directed by Manish Jha 1977 Produced by Rajesh Singh Hirawat Jain and Company 2007 Dayal Creations Pvt. Ltd. Aparajito (The Unvanquished) Awara Directed and produced by Satyajit Raj Produced and directed by Raj Kapoor 1956 1951 Epic Productions R.K. Films Ltd. Black Bobby Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali Directed and produced by Raj Kapoor 2005 1973 Yash Raj Films R.K. Films Ltd. Border Charulata (The Lonely Wife) Directed and produced by J.P. Dutta Directed by Satyajit Raj 1997 1964 J.P. Films RDB Productions Chaudhvin ka Chand Dev D Directed by Mohammed Sadiq Directed by Anurag Kashyap Produced by Guru Dutt Produced by UTV Spotboy, Bindass 1960 2009 Guru Dutt Production UTV Motion Pictures, UTV Spot Boy Devdas Devdas Directed and Produced by Bimal Roy Directed and produced by Sanjay Leela Bhansali 1955 2002 Bimal Roy Productions -

Dispute Over Bombay Mansion Highlights Indo-Pakistani Tensions

Page 1 18 of 22 DOCUMENTS The Washington Post November 9, 1983, Wednesday, Final Edition Dispute Over Bombay Mansion Highlights Indo-Pakistani Tensions BYLINE: By William Claiborne, Washington Post Foreign Service SECTION: First Section; General News; A27 LENGTH: 741 words DATELINE: NEW DELHI, Nov. 8, 1983 A dispute over possession of the former Bombay home of Pakistan's founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, coupled with continuing cross allegations of interference in each other's internal affairs, has raised tensions between India and Pakistan at a time when efforts to normalize relations between the two former enemies have ground to a standstill. While the rancor over Jinnah's palatial mansion is little more than a sideshow to sporadically turbulent Indo-Pakistan relations, diplomats on both sides agreed that it is symptomatic of a fundamental lack of trust that stems from the partition of the Subcontinent in 1947 and the successive wars between the two new nations. "There seem to be second thoughts on the Indian side about normalizing relations. Maybe they think Pakistani President Mohammed Zia ul-Haq is going to be forced out, and that there's no point in talking to him now," said a Pakistani diplomat, referring to Zia's problems in controlling violent opposition protests in Sind Province. Pakistani officials said that because of the dispute over Jinnah's house, which Pakistan planned to use as a residence of the new consul general in Bombay, plans to open a consulate in India's second largest city have been scrapped. The house that Jinnah used as a base in the early days of India's independence struggle had been promised by India to Pakistan in 1976, when diplomatic relations were resumed after having been broken in the 1971 war. -

A Respite to from Fatwas

C. M. Naim A Respite to and from Fatwas, please. A messenger brought me some news. It began: Darul Uloom Deoband, the self-appointed guardian for Indian Muslims, in a Talibanesque fatwa that reeked of tribal patriarchy, has decreed that it is “haram” and illegal according to the Sharia for a family to accept a woman's earnings. Clerics at the largest Sunni Muslim seminary after Cairo's Al-Azhar said the decree flowed from the fact that the Sharia prohibited proximity of men and women in the workplace. “It is unlawful (under the Sharia law) for Muslim women to work in the government or private sector where men and women work together and women have to talk with men frankly and without a veil,” said the fatwa issued by a bench of three clerics. The decree was issued over the weekend, but became public late on Monday, seminary sources said.1 One should not shoot the messenger if one does not like the message. True. But, allow me at least to discover what was being “messaged.” Strictly speaking, it was the following exchange on the website of the Darul Ifta (‘fatwa office’) of the Deoband seminary. (http://darulifta-deoband.org/. No changes in language and punctuation have been made in all the quotations below.) From the section on women’s issues. [1] Question: 21031, India. “Asalamu-Alikum: Can muslim women in india do Govt. or Pvt. Jobs? Shall their salary be Halal or Haram or Prohibited?” [2] Answer: 21031. 04 Apr, 2010 (Fatwa: 577/381/L=1431). “It is unlawful for Muslim women to do job in government or private institutions where men and women work together and women have to talk with men frankly and without veil. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

THE ISSUE of NATIONAL INTEGRATION in BOLLYWOOD with SPECIAL REFERENCE to LAGAAN and CHAK DE! INDIA By: Shashi Prajapati

Episteme: an online interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary & multi-cultural journal Bharat College of Arts and Commerce, Badlapur, MMR, India Volume 8, Issue 2 September 2019 THE ISSUE OF NATIONAL INTEGRATION IN BOLLYWOOD WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO LAGAAN AND CHAK DE! INDIA By: Shashi Prajapati Abstract: India is a country of diverse identity where each individual identifies himself/herself with regard to his/ her class, caste, religion, gender, language, region etc. Sometimes these identities lead to the conflicting situations especially when one is obsessed with any particular identity. This may sometimes lead to the threat to our national integrity. In such a case, maintaining the togetherness becomes a tough task. The contribution of Bollywood in this regard is not encouraging especially in the last few decades. The obsession of Bollywood with hero worship has done the huge damage to our society. Most of the films in the name of national integration create a narrow vision of Hindu-Muslim harmony. Films based on public participation are rare to find. Keeping these facts into consideration, the present paper picks up two classic Bollywood movies of 21st century - Lagaan and Chak De! India which relate the story of public participation. Keywords: National Integration, Nation building process, Patriarchy, Bollywood. 60 BCAC-ISSN-2278-879 Episteme: an online interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary & multi-cultural journal Bharat College of Arts and Commerce, Badlapur, MMR, India Volume 8, Issue 2 September 2019 Introduction The date, 14th August 1947, doesn't mark the independence of India and Pakistan alone. There were 565 princely states formerly under the British control, became independent too. These princely states had two options; either to form an independent country of its own or to merge with India or Pakistan. -

'Spaces of Exception: Statelessness and the Experience of Prejudice'

London School of Economics and Political Science HISTORIES OF DISPLACEMENT AND THE CREATION OF POLITICAL SPACE: ‘STATELESSNESS’ AND CITIZENSHIP IN BANGLADESH Victoria Redclift Submitted to the Department of Sociology, LSE, for the degree of PhD, London, July 2011. Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 For Pappu 2 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Declaration I confirm that the following thesis, presented for examination for the degree of PhD at the London School of Economics and Political Science, is entirely my own work, other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. ____________________ ____________________ Victoria Redclift Date 3 Victoria Redclift 21/03/2012 Abstract In May 2008, at the High Court of Bangladesh, a ‘community’ that has been ‘stateless’ for over thirty five years were finally granted citizenship. Empirical research with this ‘community’ as it negotiates the lines drawn between legal status and statelessness captures an important historical moment. It represents a critical evaluation of the way ‘political space’ is contested at the local level and what this reveals about the nature and boundaries of citizenship. The thesis argues that in certain transition states the construction and contestation of citizenship is more complicated than often discussed. The ‘crafting’ of citizenship since the colonial period has left an indelible mark, and in the specificity of Bangladesh’s historical imagination, access to, and understandings of, citizenship are socially and spatially produced. -

We Take Pride in Jobs Well Done

We take pride in jobs well done. JAGADAMBA PRESS #128 17 - 23 January 2003 16 pages Rs 25 [email protected] Tel: (01) 521393, 543017, 547018 Fax: (01) 536390 HEMLATA RAI, with JANAK NEPAL Manjushree in ○○○○○○○○○○○○ ○○○○○○○○ NEPALGANJ hoever killed their parents, the talks to Samrat children end up in the same place. W Sangita Yadav’s father was a farmer in Leave the kids alone Banke district. The Maoists came while he was the needs of those who are already affected.” Children recruited by eating, dragged him out of his house, beat and One of the undocumented aspects of the tortured him in front of his family, and killed Maoists to carry their conflict is the growing number of internally him. Sarala Dahal’s father was a teacher in the rucksacks rest at a tea displaced families. This has increased the same district. He was killed after surrendering house in Kalikot number of children in the district headquarters, to the security forces. district in June. townships and in Kathmandu Valley who have Sarala and Sangita are both being raised in a lost their traditional village support Novelist Manjushree Thapa, author of the child shelter which has just opened in mechanisms. School closures and threats of much-acclaimed The Tutor of History has Nepalganj by the charity group, Sahara. “We forced recruitment of one child per family by a cyber-chat with fellow-author and don’t really care who killed their parents or Maoists have added to the influx of children. A compatriot, Samrat Upadhyay who has relatives, we want to protect the future of these recent survey in the insurgency hotbed of just published his second book, The Guru children, and they all get equal care here,” says Rukum alone found that out of 1,000 people of Love in the United States. -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

My Memories of M a Jinnah

My memories of M A Jinnah R C Mody is a postgraduate in Economics and a Certificated Associate of the Indian Institute of Bankers. He studied at Raj Rishi College (Alwar), Agra College (Agra), and Forman Christian College (Lahore). For over 35 years, he worked for the Reserve Bank of India, where he headed several all-India departments, and was also Principal of the RBI Staff College. Now (2011) 84 years old, he is engaged in social work, reading, writing, and travelling. He lives in New Delhi with his wife. His email address is [email protected]. R C Mody uring pre-independence days, there was a craze among youngsters to boast about how many leaders of the independence movement they had seen. Everyone wanted to excel the other in D this regard. Not only the number but also the stature of the leader mattered. I had little to report. I had grown up and spent my early boyhood in Alwar, a Princely state. Leaders of national stature rarely visited Alwar, as the freedom movement was confined largely to British India. I had not seen practically any well-known leader in person till I was in my mid-teens. When I went to college in Agra in July 1942, I hoped to meet national leaders because Agra was a leading city of British India. Alas! The Quit India movement commenced within a month. And the British government responded by locking up all the prominent leaders whom I looked forward to see. For months, we were not even aware where they were confined. -

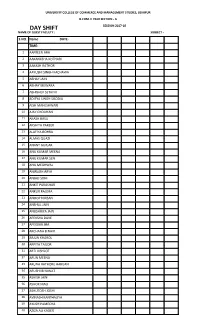

Day Shift Session 2017-18 Name of Guest Faculty : Subject - S.No

UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. II YEAR SECTION - A DAY SHIFT SESSION 2017-18 NAME OF GUEST FACULTY : SUBJECT - S.NO. Name DATE- TIME- 1 AAFREEN ARA 2 AAKANKSHA KOTHARI 3 AAKASH RATHOR 4 AAYUSHI SINGH KACHAWA 5 ABHAY JAIN 6 ABHAY MEWARA 7 ABHISHEK SETHIYA 8 ADITYA SINGH SISODIA 9 AISH MAHESHWARI 10 AJAY CHOUHAN 11 AKASH BASU 12 AKSHITA PAREEK 13 ALAFIYA BOHRA 14 ALMAS QUAZI 15 ANANT GURJAR 16 ANIL KUMAR MEENA 17 ANIL KUMAR SEN 18 ANIL MEGHWAL 19 ANIRUDH ARYA 20 ANJALI SONI 21 ANKIT PARASHAR 22 ANKUR RAJORA 23 ANOOP NIRBAN 24 ANSHUL JAIN 25 ANUSHRIYA JAIN 26 APEKSHA DAVE 27 APEKSHA JHA 28 ARCHANA B NAIR 29 ARJUN KHAROL 30 ARPITA TAILOR 31 ARTI VISHLOT 32 ARUN MEENA 33 ARUNA RATHORE HARIJAN 34 ARUSHI BIYAWAT 35 ASHISH JAIN 36 ASHOK MALI 37 ASHUTOSH JOSHI 38 AVINASH KANTHALIYA 39 AYUSH PAMECHA 40 AZIZA ALI KADER 41 BATUL 42 BHARAT LOHAR 43 BHARAT MEENA 44 BHARAT PURI GOSWAMI 45 BHAVIN JAIN 46 BHAWANA SOLANKI 47 BHUMIKA JAIN 48 BHUMIKA PALIYA 49 BHUMIT SEVAK 50 BHUPENDRA JAIN 51 BINISH KHAN 52 BURHANUDDIN MOOMIN 53 CHANCHAL SOLANKI 54 CHETAN KOTIA 55 DAKSH VYAS 56 DANISH KHAN 57 DARSHIT DOSHI 58 DEEPAK NAGDA 59 DEEPAK SHRIMALI 60 DEEPIKA SAHU 61 DEEPIKA SINGH KHARWAR 62 DEEPIKA YADAV 63 DEEPTI KUMAWAT 64 DHRUVIT KUMAWAT 65 DIKSHANT VAIRAGI 66 DINESH KUMAR MEENA 67 DINESH NAGDA 68 DINESH RAJPUROHIT 69 DIPESH JAIN 70 DIVYA GUPTA 71 DIVYA JAIN 72 DIVYA MALI 73 DIVYA NAKWAL 74 DIVYA SONI 75 DURGA BHATT 76 DURGA SHANKAR MALI 77 FATEMA BOHRA 78 FIRDOSH MANSURI 79 GAJENDRA MENARIA 80 GAJENDRA PUSHKARNA Signature of Guest Faculty DEAN UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMERCE AND MANAGEMENT STUDIES, UDAIPUR B.COM. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions.