History of Psychopharmacology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Redlands Psychiatrist Referral List Most Major Insurances Accepted Including Medi-Medi and Other Government (909) 335-3026 Insurances

University of Redlands Psychiatrist Referral List Most major insurances accepted including medi-medi and other government (909) 335-3026 insurances. But not limited to Aetna HMO/PPO, Cigna, TRIWEST, MANAGED Inland Psychiatric Medical Group 1809 W. Redlands Blvd. HEALTH NETWORK, Universal care (only for brand new day), Blue Shield, IEHP, http://www.inlandpsych.com/ Redlands, CA 92373 PPO / Most HMO, MEDICARE, Blue Cross Blue Shield, KAISER (with referral), BLUE CROSS / ANTHEM, HeathNet Providers available at this SPECIALTIES location: Chatsuthiphan, Visit MD Anxiety Disorder, Appointments-weekend, Bipolar Disorders, Borderline Personality Disorders, Depression, Medication Management, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder - Ocd Belen, Nenita MD Adhd/Add, Anxiety Disorder, Appointments-weekend, Bipolar Disorders, Depression, Medication Management, Meet And Greet, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder - Ocd, Panic Disorders, Phobias, Ptsd Adhd/Add, Adoption Issues, Aids/Hiv, Anger Management, Anxiety Disorder, Bipolar Disorders, Borderline Personality Disorders, Desai, David MD Conduct/Disruptive Disorder, Depression, Dissociative Disorder, Medication Management Farooqi, Mubashir MD Addictionology (md Only), Adhd/Add, Anxiety Disorder, Appointments-evening, Appointments-weekend, Bipolar Disorders, Conduct/Disruptive Disorder, Depression, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder - Ocd, Ptsd Julie Wareham, MD General Psychiatry, Inpatient hospital coverage for adolescent, adult, chemical dependency and consult and liaison services. Sigrid Formantes, MD General Psychiatry, General Psychiatrist Neelima Kunam, MD General Psychiatry, Adult Psychiatrist General Psychiatry, Adult Psychiatrist John Kohut, MD General Psychiatry, Adult Psychiatrist Anthony Duk, MD InlandPsych Redlands, Inc. (909)798-1763 http://www.inlandpsychredlands.com 255 Terracina Blvd. St. 204, Most major health insurance plans accepted, including student insurance Redlands, CA 92373 Providers available at this SPECIALTIES location: * Paladugu, Geetha K. MD Has clinical experience in both inpatient and outpatient settings. -

First Episode Psychosis an Information Guide Revised Edition

First episode psychosis An information guide revised edition Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) i First episode psychosis An information guide Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Sarah, 1969-, author First episode psychosis : an information guide : a guide for people with psychosis and their families / Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont), Monica Choi, MD, Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT). -- Revised edition. Revised edition of: First episode psychosis / Donna Czuchta, Kathryn Ryan. 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77052-595-5 (PRINT).--ISBN 978-1-77052-596-2 (PDF).-- ISBN 978-1-77052-597-9 (HTML).--ISBN 978-1-77052-598-6 (ePUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77114-224-3 (Kindle) 1. Psychoses--Popular works. I. Choi, Monica Arrina, 1978-, author II. Faruqui, Sabiha, 1983-, author III. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body IV. Title. RC512.B76 2015 616.89 C2015-901241-4 C2015-901242-2 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2007, 2015 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alterna- tive formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : Le premier épisode psychotique : Guide pour les personnes atteintes de psychose et leur famille This guide was produced by CAMH Publications. -

Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health

APA Resource Document Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health Approved by the Joint Reference Committee, June 2020 "The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this report do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association. Views expressed are those of the authors." —APA Operations Manual. Prepared by Ole Thienhaus, MD, MBA (Chair), Laura Halpin, MD, PhD, Kunmi Sobowale, MD, Robert Trestman, PhD, MD Preamble: The relevance of social and structural factors (see Appendix 1) to health, quality of life, and life expectancy has been amply documented and extends to mental health. Pertinent variables include the following (Compton & Shim, 2015): • Discrimination, racism, and social exclusion • Adverse early life experiences • Poor education • Unemployment, underemployment, and job insecurity • Income inequality • Poverty • Neighborhood deprivation • Food insecurity • Poor housing quality and housing instability • Poor access to mental health care All of these variables impede access to care, which is critical to individual health, and the attainment of social equity. These are essential to the pursuit of happiness, described in this country’s founding document as an “inalienable right.” It is from this that our profession derives its duty to address the social determinants of health. A. Overview: Why Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Matter in Mental Health Social determinants of health describe “the causes of the causes” of poor health: the conditions in which individuals are “born, grow, live, work, and age” that contribute to the development of both physical and psychiatric pathology over the course of one’s life (Sederer, 2016). The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2014). -

Introduction to Psychopharmacology

1 Introduction to Psychopharmacology CHAPTER OUTLINE • Psychopharmacology • Why Read a Book on Psychopharmacology? • Drugs: Administered Substances That Alter Physiological Functions • Psychoactive Drugs: Described by Manner of Use • Generic Names, Trade Names, Chemical Names, and Street Names for Drugs • Drug Effects: Determined by Dose • Pharmacology: Pharmacodynamics, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacogenetics • Psychoactive Drugs: Objective and Subjective Effects • Study Designs and the Assessment of Psychoactive Drugs • Validity: Addressing the Quality and Impact of an Experiment • Animals and Advancing Medical Research • Researchers Consider Many Ethical Issues When Conducting Human Research • From Actions to Effects: Therapeutic Drug Development • Chapter Summary sychoactive substances have made an enormous impact on society. Many people regularly drink alcohol or smoke tobacco. Millions of Americans take P prescribed drugs for depression or anxiety. As students, scholars, practitioners, and everyday consumers, we may find that learning about psychoactive substances can be invaluable. The chapters in this book provide a thorough overview of the Domajor not classes of psychoactive copy, drugs, including post, their actions inor the body distributeand their effects on behavior. 1 Copyright ©2018 by SAGE Publications, Inc. This work may not be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means without express written permission of the publisher. 2 Drugs and the Neuroscience of Behavior Psychopharmacology Psychopharmacology Psychopharmacology is the study of how drugs affect mood, perception, think- Study of how drugs ing, or behavior. Drugs that achieve these effects by acting in the nervous system affect mood, perception, thinking, or behavior are called psychoactive drugs. The term psychopharmacology encompasses two large fields: psychology and pharmacology. Thus, psychopharmacology attempts to Psychoactive drugs Drugs that affect mood, relate the actions and effects of drugs to psychological processes. -

Histamine in Psychiatry: Promethazine As a Sedative Anticholinergic

BJPsych Advances (2019), vol. 25, 265–268 doi: 10.1192/bja.2019.21 CLINICAL Histamine in psychiatry: REFLECTION promethazine as a sedative anticholinergic John Cookson (strongly influenced by the ideas of Claude Bernard John Cookson, FRCPsych, FRCP, is SUMMARY and Louis Pasteur). There he met Filomena Nitti, a consultant in general adult psych- iatry for the Royal London Hospital The author reflects on discoveries over the course daughter of a former prime minister of Italy. They of a century concerning histamine as a potent and East London NHS Foundation married in 1938 and she became her husband’slife- chemical signal and neurotransmitter, the develop- Trust. He trained in physiology and long co-worker. They moved in 1947 to the pharmacology at the University of ment of antihistamines, including promethazine, Institute of Health in Rome. In 1957 he was Oxford and he has a career-long and chlorpromazine from a common precursor, interest in psychopharmacology. His and the recognition of a major brain pathway awarded a Nobel Prize for his work in developing duties have included work in psychi- involving histamine. Although chlorpromazine has drugs ‘blocking the effects of certain substances atric intensive care units since 1988. been succeeded by numerous other antipsycho- occurring in the body, especially in its blood vessels He has co-authored two editions of tics, promethazine remains the antihistamine and skeletal muscles’ (Oliverio 1994). He and his Use of Drugs in Psychiatry, published recommended for sedation in acutely disturbed by Gaskell. research student Marianne Staub introduced the Correspondence: Dr John Cookson, patients, largely because it is potently anticholiner- first antihistamine in 1937, developed by altering Tower Hamlets Centre for Mental gic at atropinic muscarinic receptors and therefore the structures of drugs found to block known trans- Health, Mile End Hospital, Bancroft anti-Parkinsonian: this means it is also useful in mitters – acetylcholine and adrenaline – such as atro- Road, London E1 4DG, UK. -

History of Psychiatry

History of Psychiatry http://hpy.sagepub.com/ Psychiatric 'diseases' in history David Healy History of Psychiatry 2014 25: 450 DOI: 10.1177/0957154X14543980 The online version of this article can be found at: http://hpy.sagepub.com/content/25/4/450 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for History of Psychiatry can be found at: Email Alerts: http://hpy.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://hpy.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://hpy.sagepub.com/content/25/4/450.refs.html >> Version of Record - Nov 13, 2014 What is This? Downloaded from hpy.sagepub.com by guest on November 13, 2014 HPY0010.1177/0957154X14543980History of PsychiatryHealy 543980research-article2014 Article History of Psychiatry 2014, Vol. 25(4) 450 –458 Psychiatric ‘diseases’ in history © The Author(s) 2014 Reprints and permissions: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0957154X14543980 hpy.sagepub.com David Healy Bangor University Abstract A history of psychiatry cannot step back from the question of psychiatric diseases, but the field has in general viewed psychiatric entities as manifestations of the human state rather than medical diseases. There is little acknowledgement that a true disease is likely to rise and fall in incidence. In outlining the North Wales History of Mental Illness project, this paper seeks to provide some evidence that psychiatric diseases do rise and fall in incidence, along with evidence as to how such ideas are received by other historians of psychiatry and by biological psychiatrists. Keywords Disease, historical epidemiology, medical progress, post-partum psychoses, schizophrenia The twenty-fifth anniversary of the History of Psychiatry provides a wonderful opportunity to celebrate its editor who has had a huge influence on all aspects of the history outlined below. -

Medication Conversion Chart

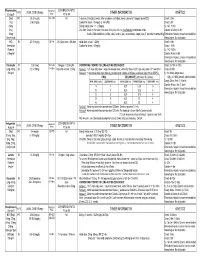

Fluphenazine FREQUENCY CONVERSION RATIO ROUTE USUAL DOSE (Range) (Range) OTHER INFORMATION KINETICS Prolixin® PO to IM Oral PO 2.5-20 mg/dy QD - QID NA ↑ dose by 2.5mg/dy Q week. After symptoms controlled, slowly ↓ dose to 1-5mg/dy (dosed QD) Onset: ≤ 1hr 1mg (2-60 mg/dy) Caution for doses > 20mg/dy (↑ risk EPS) Cmax: 0.5hr 2.5mg Elderly: Initial dose = 1 - 2.5mg/dy t½: 14.7-15.3hr 5mg Oral Soln: Dilute in 2oz water, tomato or fruit juice, milk, or uncaffeinated carbonated drinks Duration of Action: 6-8hr 10mg Avoid caffeinated drinks (coffee, cola), tannics (tea), or pectinates (apple juice) 2° possible incompatibilityElimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 5mg/ml soln Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable HCl IM 2.5-10 mg/dy Q6-8 hr 1/3-1/2 po dose = IM dose Initial dose (usual): 1.25mg Onset: ≤ 1hr Immediate Caution for doses > 10mg/dy Cmax: 1.5-2hr Release t½: 14.7-15.3hr 2.5mg/ml Duration Action: 6-8hr Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable Decanoate IM 12.5-50mg Q2-3 wks 10mg po = 12.5mg IM CONVERTING FROM PO TO LONG-ACTING DECANOATE: Onset: 24-72hr (4-72hr) Long-Acting SC (12.5-100mg) (1-4 wks) Round to nearest 12.5mg Method 1: 1.25 X po daily dose = equiv decanoate dose; admin Q2-3wks. Cont ½ po daily dose X 1st few mths Cmax: 48-96hr 25mg/ml Method 2: ↑ decanoate dose over 4wks & ↓ po dose over 4-8wks as follows (accelerate taper for sx of EPS): t½: 6.8-9.6dy (single dose) ORAL DECANOATE (Administer Q 2 weeks) 15dy (14-100dy chronic administration) ORAL DOSE (mg/dy) ↓ DOSE OVER (wks) INITIAL DOSE (mg) TARGET DOSE (mg) DOSE OVER (wks) Steady State: 2mth (1.5-3mth) 5 4 6.25 6.25 0 Duration Action: 2wk (1-6wk) Elimination: Hepatic to inactive metabolites 10 4 6.25 12.5 4 Hemodialysis: Not dialyzable 20 8 6.25 12.5 4 30 8 6.25 25 4 40 8 6.25 25 4 Method 3: Admin equivalent decanoate dose Q2-3wks. -

From Sacred Plants to Psychotherapy

From Sacred Plants to Psychotherapy: The History and Re-Emergence of Psychedelics in Medicine By Dr. Ben Sessa ‘The rejection of any source of evidence is always treason to that ultimate rationalism which urges forward science and philosophy alike’ - Alfred North Whitehead Introduction: What exactly is it that fascinates people about the psychedelic drugs? And how can we best define them? 1. Most psychiatrists will define psychedelics as those drugs that cause an acute confusional state. They bring about profound alterations in consciousness and may induce perceptual distortions as part of an organic psychosis. 2. Another definition for these substances may come from the cross-cultural dimension. In this context psychedelic drugs may be recognised as ceremonial religious tools, used by some non-Western cultures in order to communicate with the spiritual world. 3. For many lay people the psychedelic drugs are little more than illegal and dangerous drugs of abuse – addictive compounds, not to be distinguished from cocaine and heroin, which are only understood to be destructive - the cause of an individual, if not society’s, destruction. 4. But two final definitions for psychedelic drugs – and those that I would like the reader to have considered by the end of this article – is that the class of drugs defined as psychedelic, can be: a) Useful and safe medical treatments. Tools that as adjuncts to psychotherapy can be used to alleviate the symptoms and course of many mental illnesses, and 1 b) Vital research tools with which to better our understanding of the brain and the nature of consciousness. Classifying psychedelic drugs: 1,2 The drugs that are often described as the ‘classical’ psychedelics include LSD-25 (Lysergic Diethylamide), Mescaline (3,4,5- trimethoxyphenylathylamine), Psilocybin (4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) and DMT (dimethyltryptamine). -

Neuroprotection by Chlorpromazine and Promethazine in Severe Transient and Permanent Ischemic Stroke

Mol Neurobiol (2017) 54:8140–8150 DOI 10.1007/s12035-016-0280-x Neuroprotection by Chlorpromazine and Promethazine in Severe Transient and Permanent Ischemic Stroke Xiaokun Geng1,2 & Fengwu Li1 & James Yip2 & Changya Peng2 & Omar Elmadhoun2 & Jiamei Shen1 & Xunming Ji1,3 & Yuchuan Ding1,2 Received: 29 June 2016 /Accepted: 31 October 2016 /Published online: 28 November 2016 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2016 Abstract Previous studies have demonstrated depressive or enhance C + P-induced neuroprotection. C + P therapy im- hibernation-like roles of phenothiazine neuroleptics [com- proved brain metabolism as determined by increased ATP bined chlorpromazine and promethazine (C + P)] in brain levels and NADH activity, as well as decreased ROS produc- activity. This ischemic stroke study aimed to establish neuro- tion. These therapeutic effects were associated with alterations protection by reducing oxidative stress and improving brain in PKC-δ and Akt protein expression. C + P treatments con- metabolism with post-ischemic C + P administration. ferred neuroprotection in severe stroke models by suppressing Sprague-Dawley rats were subjected to transient (2 or 4 h) the damaging cascade of metabolic events, most likely inde- middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) followed by 6 or pendent of drug-induced hypothermia. These findings further 24 h reperfusion, or permanent (28 h) MCAO without reper- prove the clinical potential for C + P treatment and may direct fusion. At 2 h after ischemia onset, rats received either an us closer towards the development of an efficacious neuropro- intraperitoneal (IP) injection of saline or two doses of C + P. tective therapy. Body temperatures, brain infarct volumes, and neurological deficits were examined. -

Is Aristada (Aripiprazole Lauroxil) a Safe and Effective Treatment for Schizophrenia in Adult Patients? Kyle J

Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine DigitalCommons@PCOM PCOM Physician Assistant Studies Student Student Dissertations, Theses and Papers Scholarship 2017 Is Aristada (Aripiprazole Lauroxil) a Safe and Effective Treatment For Schizophrenia In Adult Patients? Kyle J. Knowles Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/pa_systematic_reviews Part of the Psychiatry Commons Recommended Citation Knowles, Kyle J., "Is Aristada (Aripiprazole Lauroxil) a Safe and Effective Treatment For Schizophrenia In Adult Patients?" (2017). PCOM Physician Assistant Studies Student Scholarship. 381. https://digitalcommons.pcom.edu/pa_systematic_reviews/381 This Selective Evidence-Based Medicine Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Dissertations, Theses and Papers at DigitalCommons@PCOM. It has been accepted for inclusion in PCOM Physician Assistant Studies Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@PCOM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Is Aristada (Aripiprazole Lauroxil) a Safe and Effective Treatment For Schizophrenia In Adult Patients? Kyle J. Knowles, PA-S A SELECTIVE EVIDENCE BASED MEDICINE REVIEW In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For The Degree of Master of Science In Health Sciences- Physician Assistant Department of Physician Assistant Studies Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine Philadelphia, Pennsylvania December 16, 2016 ABSTRACT OBJECTIVE: The objective of this selective EBM review is to determine whether or not “Is Aristada (aripiprazole lauroxil) a safe and effective treatment for schizophrenia in adult patients?” STUDY DESIGN: Review of three randomized controlled studies. All three trials were conducted between 2014 and 2015. DATA SOURCES: One randomized, controlled trial and two randomized, controlled, double- blind trials found via Cochrane Library and PubMed. -

Jean Delay Preamble

1 Barry Blackwell: Pioneers and Controversies in Psychopharmacology Chapter Six: Jean Delay Preamble Jean Delay is perhaps best remembered for the discovery of Chlorpromazine, the first effective drug for the treatment resistant psychotic men and women who filled the world’s asylums in the mid twentieth century. Compared to Delay’s other scientific and literary accomplishments, as told in Driss Moussai’s biography, his role in this discovery was largely conceptual and clinically modest, but as was customary in hierarchical French academia, Delay’s name came first on scientific publications. The clinical work was conducted by Pierre Deniker and an intern in his department, J.M. Harl, who died prematurely in a mountain climbing accident. Deniker described the early work in detail (Deniker, 1970) when he received the Taylor Manor Award for the discovery and presented his paper, “Introduction of Neuroleptic Chemotherapy.” “Logically a new drug was tried in cases resistant to all existing therapies. We had scarcely treated 10 patients - with all due respect to fervent adherents of statistics - when our conviction proved correct. It was supported by the sudden, great interest of nursing personnel, who had always been reserved about innovations.” When the first paper was presented to the French Medico-Psychological Society at a meeting on shock or sleep therapy the effect was described as ”neuroleptic” – effecting the neuron - in cases of “manic excitation, and more generally, psychotic patients who were often resistant to shock or sleep therapy.” The specific effects were noted on “agitation, aggressiveness and delusive conditions of schizophrenia which improved. Contact with patients could be re-established, but deficiency symptoms did not change markedly.” When six definitive papers were published between May and June 1952 these observations had been made on only 38 patients without any attempt at controlled design (Delay, Deniker and Harl 1952). -

S1 Table. List of Medications Analyzed in Present Study Drug

S1 Table. List of medications analyzed in present study Drug class Drugs Propofol, ketamine, etomidate, Barbiturate (1) (thiopental) Benzodiazepines (28) (midazolam, lorazepam, clonazepam, diazepam, chlordiazepoxide, oxazepam, potassium Sedatives clorazepate, bromazepam, clobazam, alprazolam, pinazepam, (32 drugs) nordazepam, fludiazepam, ethyl loflazepate, etizolam, clotiazepam, tofisopam, flurazepam, flunitrazepam, estazolam, triazolam, lormetazepam, temazepam, brotizolam, quazepam, loprazolam, zopiclone, zolpidem) Fentanyl, alfentanil, sufentanil, remifentanil, morphine, Opioid analgesics hydromorphone, nicomorphine, oxycodone, tramadol, (10 drugs) pethidine Acetaminophen, Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (36) (celecoxib, polmacoxib, etoricoxib, nimesulide, aceclofenac, acemetacin, amfenac, cinnoxicam, dexibuprofen, diclofenac, emorfazone, Non-opioid analgesics etodolac, fenoprofen, flufenamic acid, flurbiprofen, ibuprofen, (44 drugs) ketoprofen, ketorolac, lornoxicam, loxoprofen, mefenamiate, meloxicam, nabumetone, naproxen, oxaprozin, piroxicam, pranoprofen, proglumetacin, sulindac, talniflumate, tenoxicam, tiaprofenic acid, zaltoprofen, morniflumate, pelubiprofen, indomethacin), Anticonvulsants (7) (gabapentin, pregabalin, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, valproic acid, lacosamide) Vecuronium, rocuronium bromide, cisatracurium, atracurium, Neuromuscular hexafluronium, pipecuronium bromide, doxacurium chloride, blocking agents fazadinium bromide, mivacurium chloride, (12 drugs) pancuronium, gallamine, succinylcholine