Eating Disorders: About More Than Food

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Episode Psychosis an Information Guide Revised Edition

First episode psychosis An information guide revised edition Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) i First episode psychosis An information guide Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont) Monica Choi, MD, FRCPC Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT) A Pan American Health Organization / World Health Organization Collaborating Centre ii Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Bromley, Sarah, 1969-, author First episode psychosis : an information guide : a guide for people with psychosis and their families / Sarah Bromley, OT Reg (Ont), Monica Choi, MD, Sabiha Faruqui, MSc (OT). -- Revised edition. Revised edition of: First episode psychosis / Donna Czuchta, Kathryn Ryan. 1999. Includes bibliographical references. Issued in print and electronic formats. ISBN 978-1-77052-595-5 (PRINT).--ISBN 978-1-77052-596-2 (PDF).-- ISBN 978-1-77052-597-9 (HTML).--ISBN 978-1-77052-598-6 (ePUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77114-224-3 (Kindle) 1. Psychoses--Popular works. I. Choi, Monica Arrina, 1978-, author II. Faruqui, Sabiha, 1983-, author III. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, issuing body IV. Title. RC512.B76 2015 616.89 C2015-901241-4 C2015-901242-2 Printed in Canada Copyright © 1999, 2007, 2015 Centre for Addiction and Mental Health No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the publisher—except for a brief quotation (not to exceed 200 words) in a review or professional work. This publication may be available in other formats. For information about alterna- tive formats or other CAMH publications, or to place an order, please contact Sales and Distribution: Toll-free: 1 800 661-1111 Toronto: 416 595-6059 E-mail: [email protected] Online store: http://store.camh.ca Website: www.camh.ca Disponible en français sous le titre : Le premier épisode psychotique : Guide pour les personnes atteintes de psychose et leur famille This guide was produced by CAMH Publications. -

Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health

APA Resource Document Resource Document on Social Determinants of Health Approved by the Joint Reference Committee, June 2020 "The findings, opinions, and conclusions of this report do not necessarily represent the views of the officers, trustees, or all members of the American Psychiatric Association. Views expressed are those of the authors." —APA Operations Manual. Prepared by Ole Thienhaus, MD, MBA (Chair), Laura Halpin, MD, PhD, Kunmi Sobowale, MD, Robert Trestman, PhD, MD Preamble: The relevance of social and structural factors (see Appendix 1) to health, quality of life, and life expectancy has been amply documented and extends to mental health. Pertinent variables include the following (Compton & Shim, 2015): • Discrimination, racism, and social exclusion • Adverse early life experiences • Poor education • Unemployment, underemployment, and job insecurity • Income inequality • Poverty • Neighborhood deprivation • Food insecurity • Poor housing quality and housing instability • Poor access to mental health care All of these variables impede access to care, which is critical to individual health, and the attainment of social equity. These are essential to the pursuit of happiness, described in this country’s founding document as an “inalienable right.” It is from this that our profession derives its duty to address the social determinants of health. A. Overview: Why Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) Matter in Mental Health Social determinants of health describe “the causes of the causes” of poor health: the conditions in which individuals are “born, grow, live, work, and age” that contribute to the development of both physical and psychiatric pathology over the course of one’s life (Sederer, 2016). The World Health Organization defines mental health as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to her or his community” (World Health Organization, 2014). -

The Impact of Trauma and Attachment on Eating Disorder Symptomology

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 9-2014 The mpI act of Trauma and Attachment on Eating Disorder Symptomology Julie A. Hewett Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Hewett, Julie A., "The mpI act of Trauma and Attachment on Eating Disorder Symptomology" (2014). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 210. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/210 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOMA LINDA UNIVERSITY School of Behavioral Health in conjunction with the Faculty of Graduate Studies _______________________ The Impact of Trauma and Attachment on Eating Disorder Symptomology by Julie A. Hewett _______________________ A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical Psychology _______________________ September 2014 © 2014 Julie A. Hewett All Rights Reserved Each person whose signature appears below certifies that this dissertation in his/her opinion is adequate, in scope and quality, as a dissertation for the degree Doctor of Philosophy. , Chairperson Sylvia Herbozo, Assistant Professor of Psychology Jeffrey Mar, Assistant Clinical Professor, Psychiatry, School of Medicine Jason Owen, Associate Professor of Psychology David Vermeersch, Professor of Psychology iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Dr. -

Obesity with Comorbid Eating Disorders: Associated Health Risks and Treatment Approaches

nutrients Commentary Obesity with Comorbid Eating Disorders: Associated Health Risks and Treatment Approaches Felipe Q. da Luz 1,2,3,* ID , Phillipa Hay 4 ID , Stephen Touyz 2 and Amanda Sainsbury 1,2 ID 1 The Boden Institute of Obesity, Nutrition, Exercise & Eating Disorders, Faculty of Medicine and Health, Charles Perkins Centre, The University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected] 2 Faculty of Science, School of Psychology, the University of Sydney, Camperdown, NSW 2006, Australia; [email protected] 3 CAPES Foundation, Ministry of Education of Brazil, Brasília, DF 70040-020, Brazil 4 Translational Health Research Institute (THRI), School of Medicine, Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith, NSW 2751, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-02-8627-1961 Received: 11 May 2018; Accepted: 25 June 2018; Published: 27 June 2018 Abstract: Obesity and eating disorders are each associated with severe physical and mental health consequences, and individuals with obesity as well as comorbid eating disorders are at higher risk of these than individuals with either condition alone. Moreover, obesity can contribute to eating disorder behaviors and vice-versa. Here, we comment on the health complications and treatment options for individuals with obesity and comorbid eating disorder behaviors. It appears that in order to improve the healthcare provided to these individuals, there is a need for greater exchange of experiences and specialized knowledge between healthcare professionals working in the obesity field with those working in the field of eating disorders, and vice-versa. Additionally, nutritional and/or behavioral interventions simultaneously addressing weight management and reduction of eating disorder behaviors in individuals with obesity and comorbid eating disorders may be required. -

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical

ICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetical Order by Description IICD-10 Mental Health Billable Diagnosis Codes in Alphabetic Order by Description Note: SSIS stores ICD-10 code descriptions up to 100 characters. Actual code description can be longer than 100 characters. ICD-10 Diagnosis Code ICD-10 Diagnosis Description F40.241 Acrophobia F41.0 Panic Disorder (episodic paroxysmal anxiety) F43.0 Acute stress reaction F43.22 Adjustment disorder with anxiety F43.21 Adjustment disorder with depressed mood F43.24 Adjustment disorder with disturbance of conduct F43.23 Adjustment disorder with mixed anxiety and depressed mood F43.25 Adjustment disorder with mixed disturbance of emotions and conduct F43.29 Adjustment disorder with other symptoms F43.20 Adjustment disorder, unspecified F50.82 Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder F51.02 Adjustment insomnia F98.5 Adult onset fluency disorder F40.01 Agoraphobia with panic disorder F40.02 Agoraphobia without panic disorder F40.00 Agoraphobia, unspecified F10.180 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced anxiety disorder F10.14 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced mood disorder F10.150 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with delusions F10.151 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations F10.159 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced psychotic disorder, unspecified F10.181 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sexual dysfunction F10.182 Alcohol abuse with alcohol-induced sleep disorder F10.121 Alcohol abuse with intoxication delirium F10.188 Alcohol -

Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide

SPANISH CLINICAL LANGUAGE AND RESOURCE GUIDE The Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide has been created to enhance public access to information about mental health services and other human service resources available to Spanish-speaking residents of Hennepin County and the Twin Cities metro area. While every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information, we make no guarantees. The inclusion of an organization or service does not imply an endorsement of the organization or service, nor does exclusion imply disapproval. Under no circumstances shall Washburn Center for Children or its employees be liable for any direct, indirect, incidental, special, punitive, or consequential damages which may result in any way from your use of the information included in the Spanish Clinical Language and Resource Guide. Acknowledgements February 2015 In 2012, Washburn Center for Children, Kente Circle, and Centro collaborated on a grant proposal to obtain funding from the Hennepin County Children’s Mental Health Collaborative to help the agencies improve cultural competence in services to various client populations, including Spanish-speaking families. These funds allowed Washburn Center’s existing Spanish-speaking Provider Group to build connections with over 60 bilingual, culturally responsive mental health providers from numerous Twin Cities mental health agencies and private practices. This expanded group, called the Hennepin County Spanish-speaking Provider Consortium, meets six times a year for population-specific trainings, clinical and language peer consultation, and resource sharing. Under the grant, Washburn Center’s Spanish-speaking Provider Group agreed to compile a clinical language guide, meant to capture and expand on our group’s “¿Cómo se dice…?” conversations. -

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Anorexia Nervosa

NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Psychosom Med. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2012 July 1. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Psychosom Med. 2011 July ; 73(6): 491±497. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31822232bb. Post traumatic stress disorder in anorexia nervosa Mae Lynn Reyes-Rodríguez, Ph.D.1, Ann Von Holle, M.S.1, T. Frances Ulman, Ph.D.1, Laura M. Thornton, Ph.D.1, Kelly L. Klump, Ph.D.2, Harry Brandt, M.D.3, Steve Crawford, M.D.3, Manfred M. Fichter, M.D.4, Katherine A. Halmi, M.D.5, Thomas Huber, M.D.6, Craig Johnson, Ph.D.7, Ian Jones, M.D.8, Allan S. Kaplan, M.D., F.R.C.P. (C)9,10,11, James E. Mitchell, M.D. 12, Michael Strober, Ph.D.13, Janet Treasure, M.D.14, D. Blake Woodside, M.D.9,11, Wade H. Berrettini, M.D.15, Walter H. Kaye, M.D.16, and Cynthia M. Bulik, Ph.D.1,17 1 Department of Psychiatry, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC 2 Department of Psychology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 3 Department of Psychiatry, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 4 Klinik Roseneck, Hospital for Behavioral Medicine, Prien and University of Munich (LMU), Munich, Germany 5 New York Presbyterian Hospital-Westchester Division, Weill Medical College of Cornell University, White Plains, NY 6 Klinik am Korso, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany 7 Eating Recovery Center, Denver, CO 8 Department of Psychological Medicine, University of Birmingham, United Kingdom 9 Department of Psychiatry, The Toronto Hospital, Toronto, Canada 10 Center for -

Title Steatitis and Vitamin E Deficiency in Captive Olive Ridley Turtles

Steatitis and Vitamin E deficiency in captive olive ridley turtles Title (Lepidochelys olivacea) MANAWATTHANA, SONTAYA; KASORNDORKBUA, Author(s) CHAIYAN Proceedings of the 2nd International symposium on Citation SEASTAR2000 and Asian Bio-logging Science (The 6th SEASTAR2000 Workshop) (2005): 85-87 Issue Date 2005 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/44090 Right Type Conference Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Steatitis and Vitamin E deficiency in captive olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) SONTAYA MANAWATTHANA1 and CHAIYAN KASORNDORKBUA2 1Phuket Marine Biological Center, 51 Sakdidach Rd. Phuket 83000, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, Department of Veterinary Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Kasetsart University, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10903, Thailand. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Steatitis, which is caused by vitamin E deficiency, was observed in 3 captive Olive Ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) at Phuket Marine Biological Center, Phuket Province, Thailand during March to August 2005. Clinical findings had only shown depression and emaciation. Necropsy had revealed firm yellowish-brown masses distributed in fat tissues throughout the body. The predisposing cause of the disease is considered to be resulting from feeding these turtles mainly with frozen fish for more than 20 years, which can lead to vitamin E deficiency. Since there has been no effective treatment for chronic vitamin E deficiency, changes of the feeding from frozen fish to fresh fish and vitamin E supplementation of 100 IU/kg of fish fed have been recommended as a preventive treatment for the rest of the sea turtles in the center. KEYWORDS: olive ridley turtle, Lepidochelys olivacea, steatitis, vitamin E INTRODUCTION membranes, by preventing lipid peroxidation of Numerous scientific evidence indicates that reactive unsaturated fatty acids i.e. -

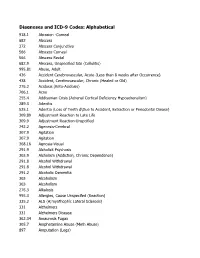

DSM III and ICD 9 Codes 11-2004

Diagnoses and ICD-9 Codes: Alphabetical 918.1 Abrasion -Corneal 682 Abscess 372 Abscess Conjunctiva 566 Abscess Corneal 566 Abscess Rectal 682.9 Abscess, Unspecified Site (Cellulitis) 995.81 Abuse, Adult 436 Accident Cerebrovascular, Acute (Less than 8 weeks after Occurrence) 438 Accident, Cerebrovascular, Chronic (Healed or Old) 276.2 Acidosis (Keto-Acidosis) 706.1 Acne 255.4 Addisonian Crisis (Adrenal Cortical Deficiency Hypoadrenalism) 289.3 Adenitis 525.1 Adentia (Loss of Teeth d\Due to Accident, Extraction or Periodontal Diease) 309.89 Adjustment Reaction to Late Life 309.9 Adjustment Reaction-Unspcified 742.2 Agenesis-Cerebral 307.9 Agitation 307.9 Agitation 368.16 Agnosia-Visual 291.9 Alcholick Psychosis 303.9 Alcholism (Addiction, Chronic Dependence) 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.8 Alcohol Withdrawal 291.2 Alcoholic Dementia 303 Alcoholism 303 Alcoholism 276.3 Alkalosis 995.3 Allergies, Cause Unspecifed (Reaction) 335.2 ALS (A;myothophic Lateral Sclerosis) 331 Alzheimers 331 Alzheimers Disease 362.34 Amaurosis Fugax 305.7 Amphetamine Abuse (Meth Abuse) 897 Amputation (Legs) 736.89 Amputation, Leg, Status Post (Above Knee, Below Knee) 736.9 Amputee, Site Unspecified (Acquired Deformity) 285.9 Anemia 284.9 Anemia Aplastic (Hypoplastic Bone Morrow) 280 Anemia Due to loss of Blood 281 Anemia Pernicious 280.9 Anemia, Iron Deficiency, Unspecified 285.9 Anemia, Unspecified (Normocytic, Not due to blood loss) 281.9 Anemia, Unspecified Deficiency (Macrocytic, Nutritional 441.5 Aneurysm Aortic, Ruptured 441.1 Aneurysm, Abdominal 441.3 Aneurysm, -

Neural Correlates and Treatments Binge Eating Disorder

Running head: Binge Eating Disorder: Neural correlates and treatments Binge Eating Disorder: Neural correlates and treatments Bachelor Degree Project in Cognitive Neuroscience Basic level 22.5 ECTS Spring term 2019 Malin Brundin Supervisor: Paavo Pylkkänen Examiner: Stefan Berglund Running head: Binge Eating Disorder: Neural correlates and treatments Abstract Binge eating disorder (BED) is the most prevalent of all eating disorders and is characterized by recurrent episodes of eating a large amount of food in the absence of control. There have been various kinds of research of BED, but the phenomenon remains poorly understood. This thesis reviews the results of research on BED to provide a synthetic view of the current general understanding on BED, as well as the neural correlates of the disorder and treatments. Research has so far identified several risk factors that may underlie the onset and maintenance of the disorder, such as emotion regulation deficits and body shape and weight concerns. However, neuroscientific research suggests that BED may characterize as an impulsive/compulsive disorder, with altered reward sensitivity and increased attentional biases towards food cues, as well as cognitive dysfunctions due to alterations in prefrontal, insular, and orbitofrontal cortices and the striatum. The same alterations as in addictive disorders. Genetic and animal studies have found changes in dopaminergic and opioidergic systems, which may contribute to the severities of the disorder. Research investigating neuroimaging and neuromodulation approaches as neural treatment, suggests that these are innovative tools that may modulate food-related reward processes and thereby suppress the binges. In order to predict treatment outcomes of BED, future studies need to further examine emotion regulation and the genetics of BED, the altered neurocircuitry of the disorder, as well as the role of neurotransmission networks relatedness to binge eating behavior. -

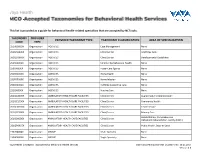

This List Is Provided As a Guide for Behavioral Health-Related Specialties That Are Accepted by Nctracks

This list is provided as a guide for behavioral health-related specialties that are accepted by NCTracks. TAXONOMY PROVIDER PROVIDER TAXONOMY TYPE TAXONOMY CLASSIFICATION AREA OF SPECIALIZATION CODE TYPE 251B00000X Organization AGENCIES Case Management None 261QA0600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Adult Day Care 261QD1600X Organization AGENCIES Clinic/Center Developmental Disabilities 251S00000X Organization AGENCIES Community/Behavioral Health None 253J00000X Organization AGENCIES Foster Care Agency None 251E00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Health None 251F00000X Organization AGENCIES Home Infusion None 253Z00000X Organization AGENCIES In-Home Supportive Care None 251J00000X Organization AGENCIES Nursing Care None 261QA3000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Augmentative Communication 261QC1500X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Community Health 261QH0100X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Health Service 261QP2300X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Primary Care Rehabilitation, Comprehensive 261Q00000X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Outpatient Rehabilitation Facility (CORF) 261QP0905X Organization AMBULATORY HEALTH CARE FACILITIES Clinic/Center Public Health, State or Local 193200000X Organization GROUP Multi-Specialty None 193400000X Organization GROUP Single-Specialty None Vaya Health | Accepted Taxonomies for Behavioral Health Services Claims and Reimbursement | Content rev. 10.01.2017 Version -

Deep Brain Stimulation in Psychiatric Practice

Clinical Memorandum Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice March 2018 Authorising Committee/Department: Board Responsible Committee/Department: Section of Electroconvulsive Therapy and Neurostimulation Document Code: CLM PPP Deep brain stimulation in psychiatric practice The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) has developed this clinical memorandum to inform psychiatrists who are involved in using DBS as a treatment for psychiatric disorders. Clinical trials into the use of Deep Brain Stimulation (DBS) to treat psychiatric disorders such as depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, substance use disorders, and anorexia are occurring worldwide, including within Australia. Although overall the existing literature shows promise for DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders, its use is still an emerging treatment and requires a stronger clinical evidence base of randomised control trials to develop a substantial body of evidence to identify and support its efficacy (Widge et al., 2016; Barrett, 2017). The RANZCP supports further research and clinical trials into the use of DBS for psychiatric disorders and acknowledges that it has potential application as a treatment for appropriately selected patients. Background DBS is an established treatment for movement disorders such as Parkinson’s disease, tremor and dystonia, and has also been used in the control of movement disorder associated with severe and medically intractable Tourette syndrome (Cannon et al., 2012). In Australia the Therapeutic Goods Administration has approved devices for DBS. It is eligible for reimbursement under the Medicare Benefits Schedule for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease but not for other neurological or psychiatric disorders. As the use of DBS in the treatment of psychiatric disorders is emerging, it is currently only available in speciality clinics or hospitals under research settings.